Bulgaria and EU Fraud: a Case of Better Late Than Never? Brendan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The European Criminal Law Associations' Forum 2013

eucrim 2013 / 4 THE EUROPEAN CRIMINAL LAW ASSOCIATIONS‘ FORUM Focus: Protection of Financial Interests of the European Union Dossier particulier: Protection des intérêts financiers de l'Union européenne Schwerpunktthema: Schutz der finanziellen Interessen der Europäischen Union Guest Editorial Viviane Reding/Algirdas Šemeta An Overall Analysis of the Proposal for a Regulation on Eurojust Prof. Dr. Anne Weyembergh The Dutch Judge of Instruction and the Public Prosecutor in International Judicial Cooperation Mr.Dr. Jaap van der Hulst The Use of Inside Information Anna Blachnio-Parzych, Ph.D. 2013 / 4 ISSUE / ÉDITION / AUSGABE The Associations for European Criminal Law and the Protection of Financial Interests of the EU is a network of academics and practitioners. The aim of this cooperation is to develop a European criminal law which both respects civil liberties and at the same time protects European citizens and the European institutions effectively. Joint seminars, joint research projects and annual meetings of the associations’ presidents are organised to achieve this aim. Contents News* Articles European Union Protection of Financial Interests of the European Union Foundations Procedural Criminal Law 127 An Overall Analysis of the Proposal 111 The Stockholm Programme 120 Procedural Safeguards for a Regulation on Eurojust 111 Schengen 121 Data Protection Prof. Dr. Anne Weyemberg 111 Enlargement Cooperation 131 The Dutch Judge of Instruction and the Institutions 122 Law Enforcement Cooperation Public Prosecutor in International Judicial 112 Commission Cooperation 113 OLAF Mr.Dr. Jaap van der Hulst 113 Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) 136 The Use of Inside Information 113 European Court of Justice (ECJ) Judgment of the European Court of Justice 114 Europol of 23 December 2009 116 Eurojust Council of Europe Anna Blachnio-Parzych, Ph.D. -

124394/EU XXIV. GP Eingelangt Am 11/09/13

124394/EU XXIV. GP Eingelangt am 11/09/13 COUNCIL OF Brussels, 10 September 2013 THE EUROPEAN UNION (OR. en) 13497/13 COMPET 638 MI 744 COVER NOTE From: Secretary-General of the European Commission, signed by Mr Jordi AYET PUIGARNAU, Director date of receipt: 1 August 2013 To: Mr Uwe CORSEPIUS, Secretary-General of the Council of the European Union No. Cion doc.: SWD(2013) 401 final Subject: COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT Regulatory Fitness and Performance Programme (REFIT): Initial Results of the Mapping of the Acquis Delegations will find attached document SWD(2013) 401 final. Encl.: SWD(2013) 401 final 13497/13 MS/ll DG G 3A EN EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 1.8.2013 SWD(2013) 401 final COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT Regulatory Fitness and Performance Programme (REFIT): Initial Results of the Mapping of the Acquis EN EN Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 4 1. Agriculture and Rural Development ............................................................................................... 5 2. Budget ........................................................................................................................................... 14 3. Climate Action .............................................................................................................................. 17 4. Communications Networks, Content and Technology ................................................................. -

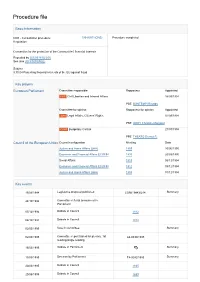

Procedure File

Procedure file Basic information CNS - Consultation procedure 1994/0911(CNS) Procedure completed Regulation Convention for the protection of the Communities' financial interests Repealed by 2012/0193(COD) See also 2015/0210(NLE) Subject 8.70.04 Protecting financial interests of the EU against fraud Key players European Parliament Committee responsible Rapporteur Appointed LIBE Civil Liberties and Internal Affairs 16/09/1994 PSE BONTEMPI Rinaldo Committee for opinion Rapporteur for opinion Appointed JURI Legal Affairs, Citizens' Rights 07/09/1994 PSE ODDY Christine Margaret CONT Budgetary Control 27/07/1994 PPE THEATO Diemut R. Council of the European Union Council configuration Meeting Date Justice and Home Affairs (JHA) 1859 20/06/1995 Economic and Financial Affairs ECOFIN 1835 20/03/1995 Social Affairs 1813 06/12/1994 Economic and Financial Affairs ECOFIN 1812 05/12/1994 Justice and Home Affairs (JHA) 1808 01/12/1994 Key events 15/06/1994 Legislative proposal published COM(1994)0214 Summary 24/10/1994 Committee referral announced in Parliament 05/12/1994 Debate in Council 1812 06/12/1994 Debate in Council 1813 02/03/1995 Vote in committee Summary 02/03/1995 Committee report tabled for plenary, 1st A4-0039/1995 reading/single reading 15/03/1995 Debate in Parliament Summary 15/03/1995 Decision by Parliament T4-0092/1995 Summary 20/03/1995 Debate in Council 1835 20/06/1995 Debate in Council 1859 26/07/1995 Act adopted by Council after consultation of Parliament 26/07/1995 End of procedure in Parliament 27/11/1995 Final act published in -

DEMELSA, Benito, “The European Union Criminal Policy Against Corruption: Two Decades of Efforts”

DEMELSA, Benito, “The European Union Criminal Policy against Corruption: Two Decades of Efforts”. Polít. crim. Vol. 15, Nº 27 (Julio 2019), Art. 15, pp. 520-548 [http://politcrim.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Vol14N27A15.pdf] The European Union Criminal Policy against Corruption: Two Decades of Efforts La política criminal de la Unión Europea contra la corrupción: dos décadas de esfuerzos Demelsa Benito Sánchez Lecturer of Criminal Law – University of Deusto (Spain) [email protected] Abstract Corruption has been in the agenda of the European Union for decades due to its devastating effects on the political and economic systems of the EU Member States, and on the European Union itself. Therefore, with the aim of combating corruption, the European Union has adopted a wide list of legal instruments since the middle of the nineties that Member States shall implement and enforce. This paper offers a critical review of the main instruments, from the first initiatives, adopted already two decades ago, until the most recent ones, focusing on the criminal law obligations they impose on the Member States. Likewise, it analyses the implementation and enforcement of such documents by Member States, with the final purpose of assessing if the European Union criminal policy against corruption is working correctly or, by contrast, needs to be improved. Keywords: Corruption, criminal policy, European Union, Member State, public official. Resumen La corrupción ha estado presente en la agenda de la Unión Europea desde hace décadas debido a sus devastadores efectos sobre los sistemas políticos y económicos de los Estados Miembros, y sobre la propia Unión Europea. -

John A.E. Vervaele EUROPEAN CRIMINAL JUSTICE IN

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Trento : UNITN-eprints John A.E. Vervaele EUROPEAN CRIMINAL JUSTICE IN THE POST-LISBON AREA OF FREEDOM, SECURITY AND JUSTICE with a prologue by Gabriele Fornasari and Daria Sartori (Eds.) 2014 QUADERNI DELLA FACOLTÀ DI GIURISPRUDENZA 5 2014 Al fine di garantire la qualità scientifica della Collana di cui fa parte, il presente volume è stato valutato e approvato da un Referee esterno alla Facoltà a seguito di una procedura che ha garantito trasparenza di criteri valutativi, autonomia dei giudizi, anonimato reciproco del Referee nei confronti di Autori e Curatori PROPRIETÀ LETTERARIA RISERVATA © Copyright 2014 by Università degli Studi di Trento Via Calepina 14 - 38122 Trento ISBN 978-88-8443-579-8 ISSN 2284-2810 Libro in Open Access scaricabile gratuitamente dall’archivio IRIS - Anagrafe della ricerca (https://iris.unitn.it) con Creative Commons Attribuzione-Non commerciale-Non opere derivate 3.0 Italia License. Maggiori informazioni circa la licenza all’URL: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/it/legalcode Il presente volume è pubblicato anche in versione cartacea per i tipi di Editoriale Scientifica - Napoli, con ISBN 978-88-6342-692-2. Novembre 2014 John A.E. Vervaele EUROPEAN CRIMINAL JUSTICE IN THE POST-LISBON AREA OF FREEDOM, SECURITY AND JUSTICE with a prologue by Gabriele Fornasari and Daria Sartori (Eds.) Università degli Studi di Trento 2014 SUMMARY Pag. Gabriele Fornasari & Daria Sartori Prologue .......................................................................................... 1 PART I EUROPEAN CRIMINAL JUSTICE AND COMBATING CRIME Chapter 1 The European Union and Harmonization of the Criminal Law Enforcement of Union Policies: In Search of a Criminal Law Policy? ............................................................................................ -

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, XXX SEC(2011)

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, XXX SEC(2011) COMMISSION STAFF WORKING PAPER […] Accompanying document to the Draft COMMISSION DECISION on establishing an EU anti-corruption reporting mechanism for periodical evaluation ("EU Anti-Corruption Report") IMPACT ASSESSMENT EN EN TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................... 3 2. PROCEDURAL ISSUES AND CONSULTATION OF INTERESTED PARTIES ............................ 3 2.1. Chronology of the Impact Assessment and results of consultations........................... 3 2.2. Consultation of Impact Assessment Board................................................................ 4 3. PROBLEM DEFINITION ................................................................................................ 4 3.1. Problem 1: High levels of corruption in some EU Member States and significant harm associated with it ............................................................................................. 5 3.2. Problem 2: Lack of common approach amongst Member States to the implementation of anti-corruption tools .................................................................. 10 3.3. Problem 3: Low confidence of EU citizens in public institutions and in the fair functioning of the market due to corruption ............................................................ 14 3.4. How would the problem evolve, all things being equal? ......................................... 15 3.5. Subsidiarity test..................................................................................................... -

THE EUROPEAN CRIMINAL LAW ASSOCIATIONS' FORUM Focus On

eucrim ISSUE / ÉDITION / AUSGABE 3–4 / 2006 THE EUROPEAN CRIMINAL LAW ASSOCIATIONS‘ FORUM SUCCESSOR TO AGON Focus on EC Competences in Criminal Matters Dossier particulier sur les compétences de la CE en matière pénale Schwerpunktthema: Kompetenzen der EG für das Strafrecht The European Community and Harmonization of the Criminal Law Enforcement of Community Policy Prof. John A.E. Vervaele Case C-176/03 and Options for the Development of a Community Criminal Law Dr. Simone White The Community Competence for a Directive on Criminal Law Protection of the Financial Interests Dr. Lothar Kuhl / Dr. Bernd-Roland Killmann, M.B.L.-HSG Die Frage der Zulässigkeit der Einführung strafrechtlicher Verordnungen des Rates der EG zum Schutz der Finanzinteressen der Europäischen Gemeinschaft Dr. Ingo E. Fromm 3 –4 / 2006 ISSUE / ÉDITION / AUSGABE Contents Index / Inhalt Editorial News* Articles Actualités / Kurzmeldungen Articles / Artikel European Union EC Competences in Criminal Matters Foundations 46 The Hague Programme Review 70 Customs Cooperation ��87 The European Community and 48 Passerelle 72 Police Cooperation Harmonization of the Criminal Law 48 PNR Data 73 Judicial Cooperation Enforcement of Community Policy 73 European Arrest Warrant (EAW) Prof. John A.E. Vervaele Institutions 74 Confiscation Orders 49 Council 74 European Supervision Order 93 Case C-176/03 and Options for 49 OLAF 75 Transfer of Sentenced Persons the Development of a Community 50 Europol 76 Exchange of Information on Criminal Law 53 Eurojust Criminal Records Dr. Simone White 53 European Union Agency for 78 Crime Statistics Fundamental Rights 78 External Dimension 100 The Community Competence for a Directive on Criminal Law Protection Specific Areas of Crime / Substantive of the Financial Interests Criminal Law Council of Europe Dr. -

International Cooperation in Criminal Matters in the European Union

Judit Harmati - Liliana Laris - Tamas Meresz Public Prosecutor trainees of Hungary consultant: Barna Miskolczi Public Prosecutor International Cooperation in Criminal Matters in the European Union THEMIS Intitial Training International Competition - Third Edition – National Institute of Magistracy Bucharest, 2008 Table of Contents I. Introduction 3 II. Historical Background 4 1. The beginning 4 2. Development of special cooperation 5 III. Procedure on the protection of financial interests 7 1. "Battle of competences" in the range of criminal cooperation 7 2. Special cooperation in the European Union in criminal matters – comparing traditional mutual assistance and cooperation in criminal matters towards the community budget 9 IV. Criminal regulation protecting the financial interests 11 1. Reasons 11 2. Infringement subject of the PIF Convention 11 3. Examples of conduct 12 4. Conducts in the PIF Convention 14 5. The Hungarian provisions 14 V. The European Anti-Fraud Office - OLAF 16 VI. Future – de lege ferenda 20 VII. Bibliography 23 Legal background 23 Case law 24 Hungarian law 24 2 I. Introduction Our document is concerned with the theme of international cooperation in criminal matters. We focus on a relatively new way of cooperation, which is still in conformation, but already has some special attributes that separate it from the traditional forms. The protection of financial interests of the European Communities has developed together with the integration itself. The community budget as special infringement subject needs special action by the Member States and the EC acting together, in cooperation with each other. This is different from the usual forms of mutual assisstance and develops new ways of cooperation protecting supranational interest utilizing –as we try to present it in our document- means of substantive and procedural law and the case law of the European Court of Justice. -

PL9700097 12 the Henryk Niewodniczariski Institute of Nuclear Physics Main Site: Ul

Rptft m\ PL9700097 12 The Henryk Niewodniczariski Institute of Nuclear Physics Main site: ul. Radzikowskiego 152 31-342 Krak6w tel: (4812) 37 00 40 fax:(4812)37 5441 tlx:3224 61 e-mail: [email protected] High Energy Department: ul. Kawiory 26 A 30-055 Krakow tel: (4812) 33 33 66, 33 68 02 fax:(4812)3338 84 tlx: 32 22 94 e-mail: [email protected] 2 8 Ns 0 6 Krakow 1995 Report No 1693 PRINTED AT THE HENRYK NIEWODNICZANSKI INSTITUTE OF NUCLEAR PHYSICS Cover designed by Jerzy Grebosz Editorial Board: J. Bartke, D. Erbel (Secretary), L. Freindl, W. Krupiriski, M. Krygowska-Doniec, J. Lekki, P. Malecki and H. Wojciechowski. e-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] The Editors assume no responsibility for the contents of materials supplied by the INP departments and laboratories. Kopia offsetowa, druk i oprawa : DRUKARNIA IFJ. Wspolpraca wydawnicza: SEKCJA WYDAWNICTW DZIALU INFORMACJI NAUKOWEJ IFJ Wydanie I zam. 15/95 Naklad 450 egz. The Henryic Niewodniczansla institute, oj Nuclear Physics, 4.0-years oj Activity in 1955, after the jirst Geneva Conference on Peacejul Use oj Atomic Energy, the Government oj Poland decided to enter the jleld oj nuclear research, it was decided at the time to buy in the Soviet Union two large installations: a 10 MW swmming pool reactor and a 120 cm classical cyclotron. The reactor, named Euia, xuas located in a small village Swierlc so tern out oj Warsaw and the u-izo cyclotron was situated at its site in Bronourice, a suburb oj Krakow. -

Introduction to the PIF Directive and Particularities Regarding Its Implementation in the Member States

Introduction to the PIF Directive and particularities regarding its implementation in the Member States ERA Workshop Competences of the EPPO and Cooperation with National Authorities Trier, 16-17 May 2019 Andrea Venegoni The content of this document represents the views of the author only and is his/her sole responsibility. The European Commission does not accept any responsibility for This programme was funded by the European Union’s Justice Programme (2014 -2020) use that may be made of the information it contains. European criminal law ●Until the end of the 80s criminal law does not belong to the competence of the EC, but to the States 1 First evolution •Need for protection of certain European interests •Possibility for the Community to request the MS to provide sanctions for the violations of the Community law •CoJ decision 21.9.1989 in case C-68/88 (Greek mais): the MS must provide sanctions for the violations of the Community law •The sanctions must be «effective, proportionate and dissuasive» Maastricht Treaty •Establishment of the Third Pillar on the judicial cooperation, also in criminal law •Possible harmonisation of the national substantive criminal law to ensure the judicial cooperation, by mean of Conventions, Common actions, Common positions and later Framework Decisions 2 Example of harmonisation •EU Convention on the Protection of the financial interests of the EU (1995) and its protocols (1996 and 1997) •Extension of the harmonisation: criminal offences, but also at least range of sanctions Legal issues about the Third -

Scanned by Scan2net

V An EU Instrument to Counter the Trafficking in Women for Sexual Exploitation into the European Union. v !i IS Bv David Goarv Thesis submitted for TT.M in Comparative, European and International Taw. European University Institute, Florence. :! Academic vear 1998/99 j ¡i Supervisor: Professor Yota Kravaritou. Word Count: 36, 219. - /O f CULI a 'rtjjfriiitt h ita auí ti tí ti yammui*, MúúéiiíüiKtí * w European University Institute 3 0001 0034 3650 0 S ‘ ^ C K v . An EU Instrument to Counter the Trafficking in Women for Sexual Exploitation into the European Union. 4 LAW Dkfe9 È \ GEA By David Geary Thesis submitted for LL.M in Comparative, European and International Law. European University Institute, Florence. Academic year 1998/99 Supervisor: Professor Yota Kravaritou. Word Count: 36,219. ^?|nr?r!y>nt ^K*nP^rTÍ^?í! ; ir*?!;rf'?' ; I ;'-! '! ?&7-!K"*&?ñS?'J-t !"!*!>? ■■■»y "...the belief that there is no scrap of ground on which real crimes are tolerated would be an extremely effective way of preventing them .M Cesare Beccaria 1 »i * i » Table of Contents Abbreviations.................... 4 Table of Cases............................................................................................................. 6 Introduction................................................................................................................. 9 Chapter One - Trafficking in Women: Definitions and Context 1.1 Introduction 11 1.2 The Problem Stated 14 1.3 Defining Trafficking 17 1.3.1 The Definitions 20 1.3.2 What is involved in trafficking in -

Downloaded from Elgar Online at 09/25/2021 02:54:57PM Via Free Access 596 Corruption

Index accountability Alcoa World Alumina 183 institutional governance, supervision Alesina, A. 52 and regulation 158–9, 168 Alter Ego or Identification Theory, public officials and lack of criminal liability of legal persons accountability 21–2 369–70 shortcomings, international Alvarez, J. 275 framework emergence 252–3, Anechiarico, F. 268 260 Argentina, capital returns, adverse see also transparency effect on SMEs 48 accounting and auditing standards Aronoff, A. 215 financial markets, politically- Asia connected firms 104, 105, 111 microfinance institutions (MFIs) preventive and non-criminal-related 131, 133–8, 139, 144–6 measures 421–3, 427–9 see also individual countries sanctions and corporate liability 355 asset recovery 479–523 adjudication versus international banks with no physical presence in supervision see follow-up territory and not affiliated to a procedures as specific cases financial group 491–2 of international supervision, capacity-building programs 493 international supervision versus capital that originates from crime adjudication 485–6 Africa civil claims and burden of proof microfinance institutions (MFIs) 496–7 129, 131, 132–3, 139, 144–6 civil procedures and mutual legal Nigeria see Nigeria assistance requirements Nyanga Declaration on the 495–6 Recovery and Repatriation of confiscation tools and international the African Wealth 479 cooperation 497–9 African Charter on Human and contingency fee arrangements 496 Peoples’ Rights 248, 253 cultural objects, possessor in good African Union Convention on faith of stolen cultural objects Preventing and Combating 484 Corruption see AU Convention cultural objects, return of 481–3, agency model, firms and markets 486, 501 20–25 freezing or redistribution of assets Aggarwal, R.