The Maiden Possessed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moses Hayim Luzzatto's Quest for Providence

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 'Like Iron to a Magnet': Moses Hayim Luzzatto's Quest for Providence David Sclar Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/380 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] “Like Iron to a Magnet”: Moses Hayim Luzzatto’s Quest for Providence By David Sclar A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The City University of New York 2014 © 2014 David Sclar All Rights Reserved This Manuscript has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the Dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Prof. Jane S. Gerber _______________ ____________________________________ Date Chair of the Examining Committee Prof. Helena Rosenblatt _______________ ____________________________________ Date Executive Officer Prof. Francesca Bregoli _______________________________________ Prof. Elisheva Carlebach ________________________________________ Prof. Robert Seltzer ________________________________________ Prof. David Sorkin ________________________________________ Supervisory Committee iii Abstract “Like Iron to a Magnet”: Moses Hayim Luzzatto’s Quest for Providence by David Sclar Advisor: Prof. Jane S. Gerber This dissertation is a biographical study of Moses Hayim Luzzatto (1707–1746 or 1747). It presents the social and religious context in which Luzzatto was variously celebrated as the leader of a kabbalistic-messianic confraternity in Padua, condemned as a deviant threat by rabbis in Venice and central and eastern Europe, and accepted by the Portuguese Jewish community after relocating to Amsterdam. -

Surpass Shelf List

Beth Sholom B'Nai Israel Shelf List Barcode Call Author Title Cost 1001502 Daily prayer book = : Ha-Siddur $0.00 ha-shalem / translated and annotated with an introduction by Philip Birnbaum. 1000691 Documents on the Holocaust : $0.00 selected sources on the destruction of the Jews of Germany and Austria, Poland, and the Soviet Union / edited by Yitzhak Arad, Yisrael Gutman, Abraham Margaliot. 1001830 Explaining death to children / $0.00 Edited by Earl A. Grollman. 1003811 In the tradition : an anthology $0.00 of young Black writers / edited by Kevin Powell and Ras Baraka. 1003812 In the tradition : an anthology $0.00 of young Black writers / edited by Kevin Powell and Ras Baraka. 1002040 Jewish art and civilization / $0.00 editor-in-chief: Geoffrey Wigoder. 1001839 The Jews / edited by Louis $0.00 Finkelstein. 56 The last butterfly $0.00 [videorecording] / Boudjemaa Dahmane et Jacques Methe presentent ; Cinema et Communication and Film Studio Barrandov with Filmexport Czechoslovakia in association with HTV International Ltd. ; [The Blum Group and Action Media Group 41 The magician of Lublin $0.00 [videorecording] / Cannon Video. 1001486 My people's Passover Haggadah : $0.00 traditional texts, modern commentaries / edited by Lawrence A. Hoffman and David Arnow. 1001487 My people's Passover Haggadah : $0.00 traditional texts, modern commentaries / edited by Lawrence A. Hoffman and David Arnow. 1003430 The Prophets (Nevi'im) : a new $0.00 trans. of the Holy Scriptures according to the Masoretic text. Second section. 1001506 Seder K'riat Hatorah (the Torah $0.00 1/8/2019 Surpass Page 1 Beth Sholom B'Nai Israel Shelf List Barcode Call Author Title Cost service) / edited by Lawrence A. -

The Soul of a Jew and the Soul of a Non-Jew an Inconvenient Truth and the Search for an Alternative

47 The Soul of a Jew and the Soul of a Non-Jew An Inconvenient Truth and the Search for an Alternative By: HANAN BALK Holiness is not found in the human being in essence unless he sanctifies himself. According to his preparation for holiness, so the fullness comes upon him from on High. A person does not acquire holiness while inside his mother. He is not holy from the womb, but has to labor from the very day he comes into the air of the world. 1 Introduction: The Soul of a Jew is Superior to that of a Non-Jew The view expressed in the above heading—as uncomfortable and racially charged as it may be in the minds of some—was undoubtedly, as we shall show, the prominent position maintained by authorities of Jewish thought throughout the ages, and continues to be so even today. While Jewish mysticism is the source and primary expositor of this theory, it has achieved a ubiquitous presence not only in the writings of Kabbalists,2 but also in the works of thinkers found in the libraries of most observant Jews, who hardly consider themselves followers of Kabbalah. Clearly, for one committed to the Torah and its principles, it is not tenable to presume that so long as he is not a Kabbalist, such a belief need not be a part of his religious worldview. Is there an alternative view that is an equally authentic representation of Jewish thought on the subject? In response to this question, we will 1 R. Simhạ Bunim of Przysukha, Kol Simha,̣ Parshat Miketz, p. -

Adas Israel Congregation June 2017 / Sivan–Tammuz 5777 Chronicle

Adas Israel Congregation June 2017 / Sivan–Tammuz 5777 Chronicle Join us for our annual cantorial concert featuring the Argen-Cantors Chronicle • May 2017 • 1 The Chronicle Is Supported in Part by the Ethel and Nat Popick Endowment Fund clergycorner From the President By Debby Joseph Rabbi Lauren Holtzblatt In my early years of learning meditation I studied with Rabbi David Zeller (z”l), at Yakar, a wonderful synagogue in the heart of Jerusalem. I would go to his classes once a week and listen with strong intention to try to understand the practice of meditation, a practice that was changing my everyday life. During the past two years, when people Rabbi Zeller would talk often about the concept of devekut (attachment to learned that I was president of Adas Israel God) that the Hasidic masters had brought alive from teachings in the Zohar: Congregation, they inevitably cracked a “If you are already full, there is no room for God. Empty yourself like a vessel.” joke about feeling sorry for me. Never has I would try my hardest to understand what this meant, but I could not grasp that sentiment been further from the truth. I how to embody this concept, how to make it true to my own experience. have relished serving in this role. I have met How do you empty yourself? What does that feel like? many people, shared many experiences, For many years, in my own spiritual practice, I committed myself to learning and the feelings that permeated all that has meditation, sitting for 5, 10, 20, 30 minutes in silent meditation several times happened during my tenure make up one of a week. -

Gilgul/Reincarnation in Sefer Habahir, Zohar and Lurianic Kabbalah

GILGUL/REINCARNATION IN SEFER HABAHIR, ZOHAR AND LURIANIC KABBALAH 1. GILGUL IN THE EVENING SHEMA PRAYER: Master of the Universe, I herby forgive anyone who angered or antagonized me or who sinned against me - whether against my body, my property, my honor or against anything anything of mine; whether he did so accidentally , willfully, carelessly, or purposely, whether through speech, deed, thought or notion, whether in this transmigration or another בגלגול זה בין גלגול אחר- transmigration GILGUL IN SEFER HA-BAHIR, Provence, c. 1170 CE: 2. BIBLICAL PROOF TEXT R. Meir said: What is the meaning of the verse “The Lord shall reign forever, your God, O Zion, from generation to generation?” [Ps. 146:10] What [does it mean] “from generation to generation”? R. Papias said: It is written, “A generation goes, and a generation comes” ([Ecc.1:4). And R. Akiba said: [The meaning of “A generation goes and a generation comes” is that] it has already come. (Sefer Ha-Bahir, 121) 3. PARABLE OF A KING To what is this similar? To a fable about a king who owned slaves, and he dressed them with embroidered silk garments according to his best ability. They disarranged them. He expelled them and drove his presence from them, and stripped them of his garments, and they went away. The king then took the garments, washed them thoroughly until there was no soiled spot left on them and placed them to be readily used. Then the king bought other slaves and dressed them with these garments. But he did not know whether or not these slaves were good. -

AAR Online Program Book A21-118 A19-1

AAR Online Program Book November 20-23, 2004 San Antonio, Texas, USA A21-118 Religion and Science Group - Lisa L. Stenmark, San Jose State University, Presiding Theme: The Ethics of Exploration: Theological and Ethical Issues in Space Travel Panelists: Laurie Zoloth, Northwestern University Paul Root Wolpe, University of Pennsylvania John Minogue, DePaul University Shannon Lucid, NASA John Glenn, NASA A19-1 Chairs Workshop - Being a Chair in Today’s Consumer Culture: Navigating in the Knowledge Factory Friday - 9:00 am-4:00 pm Sponsored by the Academic Relations Task Force Carey J. Gifford, American Academy of Religion, Presiding Panelists: Elizabeth A. Say, California State University, Northridge Gerald S. Vigna, Alvernia College Steve Friesen, University of Missouri, Columbia Carol S. Anderson, Kalamazoo College William K. Mahony, Davidson College See the Program Highlights for a description. Separate registration is required. A19-2 AAR Board of Directors Meeting Friday - 9:00 am-5:00 pm Jane Dammen McAuliffe, Georgetown University, Presiding A19-5 Genes, Ethics, and Religion: A Blueprint for Teaching Friday - 9:00 am-5:00 pm Sponsored by the Public Understanding of Religion Committee Dena S. Davis, Cleveland-Marshall College of Law, Presiding Panelists: Suzanne Holland, University of Puget Sound Sondra Ely Wheeler, Wesley Theological Seminary Michael J. Dougherty, Hampden Sydney College A19-3 Religion and Media Workshop - Film and the Possibilities of Justice: Documentary Film in and out of the Classroom Friday - 10:00 am-6:00 pm S. Brent Plate, Texas Christian University, Presiding Panelists: Barbara Abrash, New York University Judith Helfand, Working Films Robert West, Working Films Heather Hendershot, Queens College Macky Alston, Hartley Film Foundation See the Program Highlights for a description. -

The Exalted Rebbe הצדיק הנשגב

THE EXALTED REBBE הצדיק הנשגב YESHUA IN LIGHT OF THE CHASSIDIC CONCEPTS OF DEVEKUT AND TZADDIKISM הקדמה לרעיון הדבקות בחסידות ויחסו למשיחיות ישוע THE EXALTED REBBE AN INTRODUCTION TO THE CONCEPT OF DEVEKUT AND TZADDIKISM IN CHASIDIC THOUGHT TOBY JANICKI Jewish critics of Messianic Judaism and the New Testament will often raise the argument that the Hebrew Scriptures do not set a precedent for the concept of an intercessor who stands between God and man. In other words, the idea that we need Messiah Yeshua to be the one to lead us to the Father and intercede on our behalf is not biblical. These critics state that we can approach God on our own faith and merit with no need for anyone to be a go-between. In their minds such an idea is idolatrous and completely foreign to Judaism. However, the talmudic sages of Israel developed the idea of the need for an intercessor in the con- cept of the tzaddik (“righteous one”). They, along with the later Chasidic movement, found proof for the need for an intermediary in the Torah and the rest of the Scriptures. By examining the tzaddik within Judaism we can not only defend our faith in the Master but we can also better understand His role from a Torah perspective. THE TZADDIK A true .(צדק ,is derived from the Hebrew word for “righteousness” (tzedek (צדיק) The word tzaddik tzaddik is a sinless person. Tzaddik has the sense of “one whose conduct is found to be beyond re- proach by the divine Judge.”1 According to the New Testament, there is no such person, “for all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God,”2 the only exception being Yeshua of Nazareth, who was “tempted in all things as we are, yet without sin.”3 From apostolic reckoning and the perspective of Messianic faith, Yeshua is the only true tzaddik. -

The Archetype of the Tzaddiq in Hasidic Tradition

THE ARCHETYPE OF THE TZADDIQ IN HASIDIC TRADITION A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF RELIGION AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA IN CONJUNCTION wlTH THE DEPARTMENT OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF WINNIPEG IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY YA'QUB IBN YUSUF August4, 1992 National Library B¡bliothèque nat¡onale E*E du Canada Acquisitions and D¡rection des acquisilions et B¡bliographic Services Branch des services bibliograPhiques 395 Wellinolon Slreêl 395, rue Wellington Oflawa. Oñlario Ottawa (Ontario) KlA ON4 K1A ON4 foùt t¡te vat¡e ¡élëte^ce Ou l¡te Nate élëtenæ The author has granted an L'auteur a accordé une licence irrevocable non-exclusive licence irrévocable et non exclusive allowing the National Library of permettant à la Bibliothèque Canada to reproduce, loan, nationale du Canada de distribute or sell cop¡es of reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou his/her thesis by any means and vendre des copies de sa thèse in any form or format, making de quelque manière et sous this thesis available to interested quelque forme que ce soit pour persons. mettre des exemplaires de cette thèse à la disposition des personnes intéressées. The author retains ownership of L'auteur conserve la propriété du the copyright in his/her thesis. droit d'auteur qui protège sa Neither the thesis nor substantial thèse. Ni la thèse ni des extraits extracts from it may be printed or substantiels de celle-ci ne otherwise reproduced without doivent être imprimés ou his/her permission. autrement reproduits sans son autorisation, ïsBN ø-315-7796Ø-S -

“EYDELE, the REBBE”” Justin Jaron Lewis Available Online: 05 Jun 2008

This article was downloaded by: [University of Manitoba Libraries] On: 09 September 2011, At: 10:08 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Journal of Modern Jewish Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cmjs20 ““EYDELE, THE REBBE”” Justin Jaron Lewis Available online: 05 Jun 2008 To cite this article: Justin Jaron Lewis (2007): ““EYDELE, THE REBBE””, Journal of Modern Jewish Studies, 6:1, 21-40 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14725880701192304 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and- conditions This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. Justin Jaron Lewis “EYDELE, THE REBBE” Shifting perspectives on a Jewish gender transgressor TaylorCMJS_A_219152.sgm10.1080/14725880701192304Modern1472-5886Original200761000000MarchJustinjjl@post.queensu.ca JaronLewis and& JewishArticle Francis (print)/1472-5894Francis 2007 Studies (online) Eydl of Brody was a nineteenth-century woman who took on the normally male role of a Hasidic Rebbe, perhaps with tragic consequences. -

Catalog+Electronic+Reduced.Pdf

CONTENTS Dear Friends, Slavic Studies ……………..……..……… . 2 cademic Studies Press is pleased to present a wide selection of new titles for the scholar Jewish Studies ……………..……...……. 15 A and general reader alike. True to ASP’s mission, the core of our catalog consists of titles in Jewish and Slavic Studies. Highlights include Jewish City or Inferno of Russian Israel? by Linguistics …………………….…...…… 41 Victoria Khiterer, which explores the history of the Jewish community of Kiev from the tenth ASP Open ………………………….…… 42 century to the February 1917 revolution; Watersheds: Poetics and Politics of the Danube River, New in Paperback …………………..….. 43 edited by Marijeta Bozovic and Matthew D. Miller, which comprises multidisciplinary essays using the Danube as a conduit of multidirectional migration and cultural transfers and exchange Selected Backlist …...……………........... 45 and thus, a site of transcultural engagement and instantiation of a global present; and The Image Journals …………………………….…… 49 of Jews in Contemporary China edited by James Ross and Song Lihong, which examines the image of Jews from the contemporary perspective of ordinary Chinese citizens. Series ……………….……………........... 52 Inquires ...…………………….….….……59 We are also pleased to announce the founding of several new series, many of which extend Sales Representation & Distribution …… 60 beyond the fields of Jewish and Slavic Studies. Among these are “Iranian Studies,” edited by Sussan Siavoshi (Trinity University); “Ottoman and Turkish Studies,” edited by Hakan T. Index ……………………………............. 62 Karateke (University of Chicago); “Central Asian Studies,” edited by Timothy May (University of North Georgia); “Evolution, Cognition, and the Arts,” edited by Brian Boyd (University of Auckland); and “Studies in Lexical Science,” edited by Alain Polguère (Université de Lorraine). -

Jews and the Ethnographic Impulse an International Conference February 17-18, 2013 Dogwood Room, Indiana Memorial Union Indiana University, Bloomington

Going to the People: Jews and the Ethnographic Impulse An International Conference February 17-18, 2013 Dogwood Room, Indiana Memorial Union Indiana University, Bloomington Marking 100 years since S. An-sky’s expedition, this conference brings together scholars and collectors of Jewish ethnography from the former Soviet Union, Israel, England, and North America to discuss their predecessors’ endeavors and to share their work. F E A T U R I N G Haya BAR-ITZHAK Elissa BEMPORAD Alan BERN Simon BRONNER Nathaniel DEUTSCH Valery DYMSHITS Larisa FIALKOVA David FISHMAN Halina GOLDBERG Itzik GOTTESMAN Sarah IMHOFF Jason JACKSON Sergei KAN Dov-Ber KERLER Marija KRUPOVES Mikhail KRUTIKOV Moisei LEMSTER Shaul MAGID Alexandra POLJAN Anya QUILITZSCH David RANSEL Ilana ROSEN Boris SANDLER Sebastian SCHULMAN Dmitri SLEPOVITCH Yuri VEDENYAPIN Jeffrey VEIDLINGER Deborah YALEN This conference is sponsored by the Robert A. and Sandra S. Borns Jewish Studies Program and the Dr. Alice Field Cohn Chair in Yiddish Studies Conference Organizing Committee: Professor Haya Bar-Itzhak Professor Dov-Ber Kerler Traveling the Anya Quilitszch Professor Jeffrey Veidlinger Yiddishland ROBERT A. AND SANDRA S. BORNS JEWISH STUDIES PROGRAM COLLEGE OF ARTS & SCIENCES INDIANA UNIVERSITY The Robert A. and Sandra S. Borns Jewish Studies Program Indiana University The National Yiddish Theatre ~ Folksbiene presents Traveling the Yiddishland with special guest Michael Alpert Sunday, February 17, 2013 8 pm ~ Free Admission John Waldron Arts Center 122 South Walnut Street Bloomington, Indiana Dmitri Zisl Slepovitch and his band Litvakus present a multi-media musical dialogue with Belarusian Jews who have passed a treasure trove of rarely heard gems on to a new generation. -

Gilgul and Reincarnation in Zohar

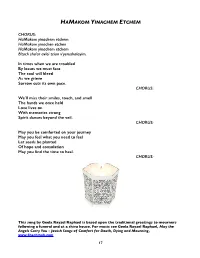

HAMAKOM YINACHEM ETCHEM CHORUS: HaMakom yinachem etchem HaMakom yinachen etchen HaMakom yinachem etchem B’toch sha’ar avlei tzion v’yerushalayim. In times when we are troubled By losses we must face The soul will bleed As we grieve Sorrow cuts its own pace.!! ! ! !!!!!!!!!!CHORUS: We’ll miss their smiles, touch, and smell The hands we once held Love lives on With memories strong Spirit dances beyond the veil.!! ! ! !!!!!!!!!!CHORUS: May you be comforted on your journey May you feel what you need to feel Let seeds be planted Of hope and consolation May you find the time to heal.!! ! ! !!!!!!!!!!CHORUS: This song by Geela Rayzel Raphael is based upon the traditional greetings to mourners following a funeral and at a shiva house. For music see Geela Rayzel Raphael, May the Angels Carry You - Jewish Songs of Comfort for Death, Dying and Mourning, www.Shechinah.com 17 GILGUL AND REINCARNATION IN ZOHAR AND LURIANIC KABBALAH HEINRICH GRAETZ ON KABBALAH & JEWISH MYSTICISM: JEWISH MYSTICAL IDEAS -> “a corruptive force throughout Jewish history” “malignant growth in the body of Judaism” KABBALAH -> “empty kabbalah could not fail to arouse enthusiasm in empty heads.” ZOHAR -> “occasionally offering a faint suggestion of an idea, which in a trice evaporates in a feverish fancies or childish silliness” HASIDISM -> “a new sect, a daughter of darkness, born in gloom, which even today proceeds stealthily on its mysterious way … [plunging east European Jewry] into a primitive state of barbarism.” (esp. Vol. IV of History of the Jews) GILGUL IN THE EVENING