Fashion's Foes: Dress Reform from 1850-1900

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evening Gown Sewing Supplies Embroidering on Lightweight Silk Satin

Evening Gown Sewing supplies Embroidering on lightweight silk satin The deLuxe Stitch System™ improves the correct balance • HUSQVARNA VIKING® DESIGNER DIAMOND between needle thread and bobbin thread. Thanks to the deLuxe™ sewing and embroidery machine deLuxe Stitch System™ you can now easily embroider • HUSQVARNA VIKING® HUSKYLOCK™ overlock with different kinds of threads in the same design. machine. • Use an Inspira® embroidery needle, size 75 • Pattern for your favourite strap dress. • Turquoise sand-washed silk satin. • Always test your embroidery on scraps of the actual fabric with the stabilizer and threads you will be using • Dark turquoise fabric for applique. before starting your project. • DESIGNER DIAMOND deLuxe™ sewing and • Hoop the fabric with tear-away stabilizer underneath embroidery machine Sampler Designs #1, 2, 3, 4, 5. and if the fabric needs more support use two layers of • HUSQVARNA VIKING® DESIGNER™ Royal Hoop tear-away stabilizer underneath the fabric. 360 x 200, #412 94 45-01 • Endless Embroidery Hoop 180 x 100, #920 051 096 Embroider and Sew • Inspira® Embroidery Needle, size 75 • To insure a good fit, first sew the dress in muslin or • Inspira® Tear-A-Way Stabilizer another similar fabric and make the changes before • Water-Soluble Stabilizer you start to cut and sew in the fashion fabric for the dress. • Various blue embroidery thread Rayon 40 wt • Sulky® Sliver thread • For the bodice front and back pieces you need to embroider the fabric before cutting the pieces. Trace • Metallic thread out the pattern pieces on the fabric so you will know how much area to fill with embroidery design #1. -

Zfwtvol. 9 No. 3 (2017) 269-288

ZfWT Vol. 9 No. 3 (2017) 269-288 FEMINIST READING OF GOTHIC SUBCULTURE: EMPOWERMENT, LIBERATION, REAPPROPRIATION Mikhail PUSHKIN∗ Abstract: Shifting in and out of public eye ever since its original appearance in the 1980ies, Gothic subculture, music and aesthetics in their impressive variety have become a prominent established element in global media, art and culture. However, understanding of their relation to female gender and expression of femininity remains ambiguous, strongly influenced by stereotypes. Current research critically analyses various distinct types of Gothic subculture from feminist angle, and positively identifies its environment as female-friendly and empowering despite and even with the help of its strongly sexualized aesthetics. Although visually geared towards the male gaze, Gothic subcultural environment enables women to harness, rather than repress the power of attraction generated by such aesthetics. Key words: Subculture, Feminism, Gothic. INTRODUCTION Without a doubt, Gothic subculture is a much-tattered subject, being at the centre of both popular mass media with its gossip, consumerism and commercialization, as well as academia with diverse papers debasing, pigeonholing and even defending the subculture. Furthermore, even within the defined, feminist, angle, a thorough analysis of Gothic subculture would require a volume of doctoral dissertation to give the topic justice. This leaves one in a position of either summarizing and reiterating earlier research (a useful endeavour, however, bringing no fresh insight), or striving for a kind of fresh look made possible by the ever-changing eclectic ambivalent nature of the subculture. Current research takes the middle ground approach: touching upon earlier research only where relevant, providing a very general, yet necessary outlook on the contemporary Gothic subculture in its diversity, so as to elucidate its more relevant elements whilst focusing on the ways in which it empowers women. -

Use and Applications of Draping in Turkey's

USE AND APPLICATIONS OF DRAPING IN TURKEY’S CONTEMPORARY FASHION DUYGU KOCABA Ş MAY 2010 USE AND APPLICATIONS OF DRAPING IN TURKEY’S CONTEMPORARY FASHION A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF IZMIR UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS BY DUYGU KOCABA Ş IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENTOF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF DESIGN IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES MAY 2010 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences ...................................................... Prof. Dr. Cengiz Erol Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Design. ...................................................... Prof. Dr. Tevfik Balcıoglu Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adaquate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Design. ...................................................... Asst. Prof. Dr. Şölen Kipöz Supervisor Examining Committee Members Asst. Prof. Dr. Duygu Ebru Öngen Corsini ..................................................... Asst. Prof. Dr. Nevbahar Göksel ...................................................... Asst. Prof. Dr. Şölen Kipöz ...................................................... ii ABSTRACT USE AND APPLICATIONS OF DRAPING IN TURKEY’S CONTEMPORARY FASHION Kocaba ş, Duygu MDes, Department of Design Studies Supervisor: Asst. Prof. Dr. Şölen K İPÖZ May 2010, 157 pages This study includes the investigations of the methodology and applications of draping technique which helps to add creativity and originality with the effects of experimental process during the application. Drapes which have been used in different forms and purposes from past to present are described as an interaction between art and fashion. Drapes which had decorated the sculptures of many sculptors in ancient times and the paintings of many artists in Renaissance period, has been used as draping technique for fashion design with the contributions of Madeleine Vionnet in 20 th century. -

Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018

The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Front Cover Image: Textile Detail of an Evening Dress, circa 1950s, Maker Unknown, Middlesex University Fashion Collection, London, England, F2021AB. The Middlesex University Fashion Collection comprises approximately 450 garments for women and men, textiles, accessories including hats, shoes, gloves, and more, plus hundreds of haberdashery items including buttons and trimmings, from the nineteenth century to the present day. Browse the Middlesex University Fashion Collection at https://tinyurl.com/middlesex-fashion. The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Editor–in–Chief Jennifer Daley Editor Scott Hughes Myerly Proofreader Georgina Chappell Published by The Association of Dress Historians [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org Copyright © 2018 The Association of Dress Historians ISSN 2515–0995 Online Computer Library Centre (OCLC) accession #988749854 The Journal of Dress History is the academic publication of The Association of Dress Historians through which scholars can articulate original research in a constructive, interdisciplinary, and peer reviewed environment. The Association of Dress Historians supports and promotes the advancement of public knowledge and education in the history of dress and textiles. The Association of Dress Historians (ADH) is Registered Charity #1014876 of The Charity Commission for England and Wales. The Journal of Dress History is copyrighted by the publisher, The Association of Dress Historians, while each published author within the journal holds the copyright to their individual article. The Journal of Dress History is circulated solely for educational purposes, completely free of charge, and not for sale or profit. -

The Morgue File 2010

the morgue file 2010 DONE BY: ASSIL DIAB 1850 1900 1850 to 1900 was known as the Victorian Era. Early 1850 bodices had a Basque opening over a che- misette, the bodice continued to be very close fitting, the waist sharp and the shoulder less slanted, during the 1850s to 1866. During the 1850s the dresses were cut without a waist seam and during the 1860s the round waist was raised to some extent. The decade of the 1870s is one of the most intricate era of women’s fashion. The style of the early 1870s relied on the renewal of the polonaise, strained on the back, gath- ered and puffed up into an detailed arrangement at the rear, above a sustaining bustle, to somewhat broaden at the wrist. The underskirt, trimmed with pleated fragments, inserting ribbon bands. An abundance of puffs, borders, rib- bons, drapes, and an outlandish mixture of fabric and colors besieged the past proposal for minimalism and looseness. women’s daywear Victorian women received their first corset at the age of 3. A typical Victorian Silhouette consisted of a two piece dress with bodice & skirt, a high neckline, armholes cut under high arm, full sleeves, small waist (17 inch waist), full skirt with petticoats and crinoline, and a floor length skirt. 1894/1896 Walking Suit the essential “tailor suit” for the active and energetic Victorian woman, The jacket and bodice are one piece, but provide the look of two separate pieces. 1859 zouave jacket Zouave jacket is a collarless, waist length braid trimmed bolero style jacket with three quarter length sleeves. -

GEORGE W. BROWN the BRUNSWICK Hotel Lenox

BOSTON, MASS., FRIDAY. APRIL 14. 1905 1 0 GEORGE W.BROWN SHIRTINGS FOR 1905 ARE READY Copley Square All the Newest Ideas for.Men's Negligee and Nvlercbant Summer Wear in Hotel SHIRTS tailor Made from English, Scotch and French Fabrics. Huntington Aoe. & Exeter St. Private Designs. BUSINESS AND DRESS 110 TREMONT STREET SUITS PATRONAGE of "Tech" students $1.50, $2.00, $3.50, $4.50, $5.50 and solicited in our Cafe and Lunch Upward Room All made 27he attention of Secretaries Makes up-to-date students' in our own workrooms. Consult us to ana know the Linen, the Cravet and Gloves to Wear. Banquet Committees of Dining clothes at very reasonable Clubs, Societies, Lodges, etc., is GLOVES called to the fact that the Copley Fownes' Heavy Square prl;r., Street Gloves, hand Hotel has exceptionally I lStitched, $1.50. Better ones, $2.00, ood facilities $2.50 and $3.00. Men's and Women's for serving Breakfasts, Luncheons or Dinners and will cater NECKWEAR out of the ordinary-shapes strictly especially to Suits and Overcoats from $35 new-8-1.00 to $4.50. this trade. Amos H. Whipple, Proprietor This is the best time of the ENTIRE YEAR, N oy s Oi /ros.' Summer Streets, for you to have your FULL DRESS, Tuxedo, Boston, U. S. A. or Double-Breasted Frock Suit made. We make a Specialty of these garments and make Special Established I874 Prices during the slack season. Then again, we SPRING OPENING have an extra large assortment at this time, and DURGIN, PARK & CO,. -

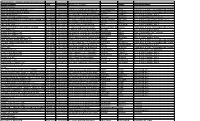

New Licenses

New Licenses - ALLIssued from 01/01/2021 to 09/01/2021 as of 09/01/2021 8:13 am Business Name Lic # IssuedDate Business Location Owner Type of Business Alcohol License 1800 MEXICAN RESTAURANT, LLC ALC13606 06/28/2021 5296 New Jesup Hwy Brunswick DURAN MARIN RAUL Liquor Beer & Wine Consumption On Premis BEACHCOMBER BBQ & GRILL ALC14200 08/25/2021 319 Arnold Rd St Simons Island PARROTT THOMAS Liquor Beer & Wine Consumption On Premis BPR BRUNSWICK LLC ALC13776 04/07/2021 116 Gateway Center Blvd BrunswickPATEL PANKAJ Beer & Wine Package Sales COBBLESTONE WHOLESALE ALC14190 08/25/2021 262 Redfern Vlg St Simons Island STEGER RHONDA Wine Consumption On Premises CRACKER BARREL OLD COUNTRY STORE, INC.ALC14060 07/26/2021 211 Warren Mason Blvd Brunswick CHRISTENSEN WILLIAM Beer & Wine Consumption On Premises DOLGENCORP,LLC ALC13837 05/13/2021 461 Palisade Dr Brunswick GILLIS MATIE Beer & Wine Package Sales DOLGENCORP,LLC ALC13923 05/12/2021 25 Cornerstone Ln Brunswick REID FEATHER Beer & Wine Package Sales DOROTHY'S COCKTAIL & OYSTER BAR ALC13687 03/19/2021 12 Market St St Simons Island AUFFENBERG JR. DANIEL Liquor Beer & Wine Consumption On Premis ELI CAIRO LLC ALC13631 01/07/2021 72 Altama Village Dr Brunswick MAZON ELI Beer & Wine Package Sales FRANCIE & MARTI LLC ALC13953 07/08/2021 295 Redfern Vlg A St Simons Island TOLLESON MARTI Wine Consumption On Premises FRANCIE & MARTI LLC ALC13954 07/08/2021 295 Redfern Vlg A St Simons Island TOLLESON MARTI Wine Package Sales GEORGIA CVS PHARMACY, LLC ALC13711 03/23/2021 1605 Frederica Rd St Simons Island -

23 Trs Male Uniform Checklist

23 TRS MALE UNIFORM CHECKLIST Rank and Name: Class: Flight: Items that have been worn or altered CANNOT be returned. Quantities listed are minimum requirements; you may purchase more for convenience. Items listed as “seasonal” will be purchased for COT 17-01 through 17-03, they are optional during the remainder of the year. All Mess Dress uniform items (marked with *) are optional for RCOT. Blues Qty Outerwear and Accessories Qty Hard Rank (shiny/pin on) 2 sets Light Weight Blues Jacket (seasonal) 1 Soft Rank Epaulets (large) 1 set Cardigan (optional) 1 Ribbon Mount varies Black Gloves (seasonal) 1 pair Ribbons varies Green Issue-Style Duffle Bag 1 U.S. Insignia 1 pair Eyeglass Strap (if needed) 1 Blue Belt with Silver Buckle 1 CamelBak Cleansing Tablet (optional) 1 Shirt Garters 1 set Tie Tack or Tie Bar (optional) 1 PT Qty Blue Tie 1 USAF PT Jacket (seasonal) 1 Flight Cap 1 USAF PT Pants (seasonal) 1 Service Dress Coat 1 USAF PT Shirt 2 sets Short Sleeve Blue Shirts 2 USAF PT Shorts 2 sets Long Sleeve Blue Shirt (optional) 1 Blues Service Pants (wool) 2 Footwear Qty White V-Neck T-shirts 3 ABU Boots Sage Green 1 pair Low Quarter Shoes (Black) 1 pair Mess Dress Qty Sage Green Socks 3 pairs White Formal Shirt (seasonal)* 1 Black Dress Socks 3 pairs Mess Dress Jacket (seasonal)* 1 White or Black Athletic Socks 3 pairs Mess Dress Trousers (seasonal)* 1 Cuff Links & Studs (seasonal)* 1 set Shoppette Items Qty Mini Medals & Mounts (seasonal)* varies Bath Towel 1 Bowtie (seasonal)* 1 Shower Shoes 1 pair -

The Shape of Women: Corsets, Crinolines & Bustles

The Shape of Women: Corsets, Crinolines & Bustles – c. 1790-1900 1790-1809 – Neoclassicism In the late 18th century, the latest fashions were influenced by the Rococo and Neo-classical tastes of the French royal courts. Elaborate striped silk gowns gave way to plain white ones made from printed cotton, calico or muslin. The dresses were typically high-waisted (empire line) narrow tubular shifts, unboned and unfitted, but their minimalist style and tight silhouette would have made them extremely unforgiving! Underneath these dresses, the wearer would have worn a cotton shift, under-slip and half-stays (similar to a corset) stiffened with strips of whalebone to support the bust, but it would have been impossible for them to have worn the multiple layers of foundation garments that they had done previously. (Left) Fashion plate showing the neoclassical style of dresses popular in the late 18th century (Right) a similar style ball- gown in the museum’s collections, reputedly worn at the Duchess of Richmond’s ball (1815) There was public outcry about these “naked fashions,” but by modern standards, the quantity of underclothes worn was far from alarming. What was so shocking to the Regency sense of prudery was the novelty of a dress made of such transparent material as to allow a “liberal revelation of the human shape” compared to what had gone before, when the aim had been to conceal the figure. Women adopted split-leg drawers, which had previously been the preserve of men, and subsequently pantalettes (pantaloons), where the lower section of the leg was intended to be seen, which was deemed even more shocking! On a practical note, wearing a short sleeved thin muslin shift dress in the cold British climate would have been far from ideal, which gave way to a growing trend for wearing stoles, capes and pelisses to provide additional warmth. -

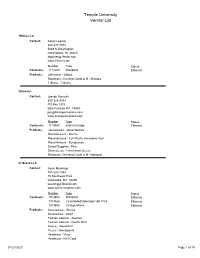

Temple University Vendor List

Temple University Vendor List 19Nine LLC Contact: Aaron Loomer 224-217-7073 5868 N Washington Indianapolis, IN 46220 [email protected] www.19nine.com Number Type Status Contracts: 1112269 Standard Effective Products: Otherwear - Shorts Stationary, Greeting Cards & N - Stickers T-Shirts - T-Shirts 3Click Inc Contact: Joseph Domosh 833-325-4253 PO Box 2315 Bala Cynwyd, PA 19004 [email protected] www.3clickpromotions.com Number Type Status Contracts: 1114550 Internal Usage Effective Products: Housewares - Water Bottles Miscellaneous - Koozie Miscellaneous - Cell Phone Accessory Item Miscellaneous - Sunglasses School Supplies - Pen Short sleeve - t-shirt short sleeve Stationary, Greeting Cards & N - Notepad 47 Brand LLC Contact: Kevin Meisinger 781-320-1384 15 Southwest Park Westwood, MA 02090 [email protected] www.twinsenterprise.com Number Type Status Contracts: 1013854 Standard Effective 1013856 Co-branded/Operation Hat Trick Effective 1013855 Vintage Marks Effective Products: Accessories - Gloves Accessories - Scarf Fashion Apparel - Sweater Fashion Apparel - Rugby Shirt Fleece - Sweatshirt Fleece - Sweatpants Headwear - Visor Headwear - Knit Caps 01/21/2020 Page 1 of 79 Headwear - Baseball Cap Mens/Unisex Socks - Socks Otherwear - Shorts Replica Football - Football Jersey Replica Hockey - Hockey Jersey T-Shirts - T-Shirts Womens Apparel - Womens Sweatpants Womens Apparel - Capris Womens Apparel - Womens Sweatshirt Womens Apparel - Dress Womens Apparel - Sweater 4imprint Inc. Contact: Karla Kohlmann 866-624-3694 101 Commerce -

The War and Fashion

F a s h i o n , S o c i e t y , a n d t h e First World War i ii Fashion, Society, and the First World War International Perspectives E d i t e d b y M a u d e B a s s - K r u e g e r , H a y l e y E d w a r d s - D u j a r d i n , a n d S o p h i e K u r k d j i a n iii BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA 29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2021 Selection, editorial matter, Introduction © Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian, 2021 Individual chapters © their Authors, 2021 Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Editors of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgments on p. xiii constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design by Adriana Brioso Cover image: Two women wearing a Poiret military coat, c.1915. Postcard from authors’ personal collection. This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third- party websites referred to or in this book. -

Undergarments : Extension Circular 4-12-2

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Nebraska 4-H Clubs: Historical Materials and Publications 4-H Youth Development 1951 Undergarments : Extension Circular 4-12-2 Allegra Wilkens Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/a4hhistory Part of the Service Learning Commons Wilkens, Allegra, "Undergarments : Extension Circular 4-12-2" (1951). Nebraska 4-H Clubs: Historical Materials and Publications. 124. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/a4hhistory/124 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the 4-H Youth Development at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska 4-H Clubs: Historical Materials and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Jan. 1951 E.G. 4-12-2 o PREPARED FOR 4-H CLOTHrNG ClUB GIRLS EXTENSION SERVICE UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND U. S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE COOPERATING A W. V. LAMBERT, DIRECTOR C i ( Undergarments for the Well Dressed 4-H Girl Allegra Wilkens The choosing or designing of the undergarments that will make a suitable foundation for her costume is a challenge to any girl's good taste. She may have attractive under- wear if she is wise in the selection of materials and careful in making it or in choosing ready-made garments. It is not the amount of money that one spends so much as it is good judgment in the choice of styles, materials and trimmings. No matter how beautiful or appropriate a girl's outer garments may be, she is not well dressed unless she has used good judgment in making or selecting her under - wear.