Transition Guide a Guide for Planning and Organizing Your

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pre-Approved Accuplacer Test Sites As of September 2019

Pre-Approved Accuplacer Test Sites As of September 2019 Alabama Andalusia Lurleen B Wallace Community College 1000 Dannelly Blvd Andalusia, AL 36420 Fee: unknown Birmingham Jefferson State Community College 2601 Carson Rd Birmingham, AL 35215 Fee: $35 Birmingham Lawson State Community College 3060 Wilson Rd Birmingham, AL 35221 Fee: unknown Boaz Snead State Community College 102 Elder St Boaz, AL 35957 Fee: unknown Decatur Calhoun Community College PO Box 2216 Decatur, AL 35609 Fee: unknown Dothan Wallace Community College, Dothan 1141 Wallace Dr Dothan, AL 36303 Fee: $25 Enterprise Enterprise State Community College PO Box 1300 Enterprise, AL 36330 Fee: unknown Eufaula Wallace Community College, Sparks Campus 3235 S Eufaula Ave Eufaula, AL 36027 Fee: $25 Huntsville Alabama A&M University 4900 Meridian Street Huntsville, AL 35811 Fee: $30 Huntsville Calhoun Community College 102B Wynn Dr Huntsville, AL 35805 Fee: Unknown Huntsville J.F. Drake State Community and Technical College 3421 Meridian St Huntsville, AL 35811 Fee: $25 Mobile Bishop State Community College 351 North Broad Street Mobile, AL 36603 Fee: unknown Monroeville Coastal Alabama Community College P O Box 2000 Monroeville, AL 36460 Fee: Unknown Opelika Southern Union State Community College 301 Lake Condy Rd Opelika, AL 36801 Fee: $25 Orange Beach Columbia Southern University, Vietnam Campus 21982 University Ln Orange Beach, AL 36561 Fee: Unknown Phenix City Chattahoochee Valley Community College 2602 College Dr Phenix City, AL 36869 Fee: $25 Troy Troy University 100 University -

AZBN Monthly Education Meeting with Arizona Nursing Assistant

AZBN Monthly Education Meeting with Arizona Nursing Assistant Programs Thursday, December 10, 2020 1:00pm Summary ➢ Welcome The meeting began at 1:00pm with Cindy George facilitating the call and Tricia Pitts will be taking notes ➢ Roll Call: Arizona Medical Training Institute Caregiver Training Institute Cibola High School - Yuma Unified School District East Valley Institute of Technology Gila Community College/Eastern Arizona College - Payson Gila Ridge High School MedStar Academy Mesa Community College - MAIN Mesa Community College - Red Mountain Campus Mohave Community College Northland Pioneer College Phoenix Job Corps Center Pima Community College Pima County JTED Pima Medical Institute Queen Creek High School Regional Center For Border Health Rio Rico High School Saguaro High School San Luis High School Star Canyon School of Nursing Valley Academy for Career and Technology Education (V'ACTE) Valley Vocational Academy West-Mec Yavapai College Yuma Union ➢ Department of Education Update for High Schools (Aden Ramirez) ○ Aden was unable to join the call today. ○ Cindy and Aden are working on starting a quarterly phone call beginning in January and all of the High School Coordinators and Instructors to discuss updates or changes. ➢ Tap changes and Candidate Handbooks on D and S site (Cindy) ○ Katy from D&S Headmaster: We now have the updated handbook on the D&S website with the new changes from the TAP Committee. The changes are currently highlighted in grey. ■ If you would like to order new handbooks, please send an email to: [email protected]. We will only send 100 copies for the first request. If your school needs more than 100 you can request more after February 1st, 2021. -

Network Emphasizes Technology, Job Creation

Network Emphasizes Technology, Job Creation Print May 2010 Vol 1. No. 3 Coming Events Front and Center By AZSBDC State Director May 20 Janice C. Washington, CPA 2010 SBA Small Business Awards, presented as part of the Focused on Economic Development 17th Annual Enterprise Awards The AZSBDC Network actively participated in the 96th Luncheon. Information HERE. See Arizona Town Hall meeting to promote needed related story for list of AZSBDC economic growth and development throughout the state. Network winners. Arizona Western College SBDC Center Director Randy Nelson and Business Analyst Alan Pruitt, May 21 Cochise College SBDC Center Director Mignonne YOB (Your Own Business) Fair Hollis and I worked hard to ensure that Arizona's small & Resource Day - Join the business community -- and its needs --- were included in the process and the AZSBDC/Maricopa SBDC, ASBA, summary report. City of Phoenix, Greater Phoenix Chamber and other top-drawer AZSBDC Network Centers are on the front line in urban and rural communities business resource partners at this throughout the state, where our team members experience firsthand the (first-ever) free event from 8 a.m. challenges that new and growing companies (and their host communities) to 5 p.m. at Deer Valley Airpark. face. The report of the 96th Arizona Town Hall (Building Arizona's Future: Information HERE. Jobs, Innovation & Competitiveness) recognizes our involvement and impact -- and also acknowledges the need for better small business program funding and capital development. June 18 Greater Phoenix Chamber Learn about the Arizona Town Hall project HERE, where Business Expo Event, held at the you can also sign up to become a corporate or individual Westin Kierland Resort in member. -

Profit Mastery SBDC Master State Licenses Arizona Connecticut

Profit Mastery SBDC Master State Licenses Arizona Connecticut Florida Illinois Montana North Texas Washington, DC West Virginia Wyoming Profit Mastery SBDC individual Center Licenses, by state Alaska SBDC 111 Stedman St Suite 201 Ketchikan AK Alaska SBDC 430 W 7th Ave Ste 110 Anchorage AK Alaska SBDC 430 W 7th Ave Ste 110 Anchorage AK Alaska SBDC 3100 Channel Dr. Suite 306 Juneau AK Alaska SBDC 43335 Kalifornsky Beach Rd. Ste 12 Soldotna AK Alaska Small Business Development Center PO Box 2968 Bethel AK Alaska Small Business Development Center 111 Stedman Street Ketchikan AK Central Alaska SBDC 201 N. Lucille St Wasilla AK SBDC Alabama State University 915 S. Jackson Street Montgomery AL Arkansas SBDC 2801 South University Ave, Rm 260 Little Rock AR Arizona SBDC P O Box 610 Holbrook AZ Arizona Western College SBDC 1351 South Redondo Center Drive Yuma AZ AZSBDC 3000 N. 4th Street Flagstaff AZ Central Arizona College SBDC 540 N. Camino Mercado, Ste. #1 Casa Grande AZ City of Peoria 9875 N. 85th Ave Peoria AZ Cochise College SBDC 901 North Colombo Ave Sierra Vista AZ Coconino Community College SBDC 3000 North 4th Street Flagstaff AZ Eastern Arizona College SBDC 615 North Stadium Ave Thatcher AZ Gila Community College SBDC 201 Mudsprings Road Payson AZ Maricopa Community College 2400 North Ave, Suite 104 Phoenix AZ 1 Alaska SBDC 111 Stedman St Suite 201 Ketchikan AK Mohave Community College SBDC 1971 Jagerson Ave Kingman AZ Northland Pioneer College SBDC PO Box 180 Springerville AZ Northland Pioneer College SBDC PO Box 610 Holbrook AZ Pima Community College SBDC 401 North Bonita Ave Tucson AZ SBDC Maricopa 3000 North Dysart Road Avondale AZ Yavapai College SBDC 240 S Montezuma St., Suite 105 Prescott AZ California SBDC 425 Belden St Gonzales CA California SBDC 100 East Santa Clara St San Jose CA California SBDC 1 Civic Center Circle Brea CA CITD 630 W 19th ST Suite 113 Merced CA Contra Costa SBDC 300 Ellinwood Way #300 Pleasant Hill CA Long Beach City College SBDC 4901 E. -

Time Pass Rates

Joey Ridenour ARIZONA STATE BOARD OF NURSING Executive Director Approved Nursing Assistant Training Programs Annual First -Time Pass Rates The following is a list of nursing assistant training programs currently approved by the Executive Director of the Arizona State Board of Nursing. Site visits are conducted on all nursing assistant programs every two years. Annual pass rates for these programs are listed for all approved programs. Candidates are required to score a minimum of 75% on the written exam which consists of 75 multiple choice questions, and 80% on the skills exam (without missing any key steps). Please contact the program directly regarding program costs, start dates and other details you may need. Note: Approvals are granted for 2 years AZ had 3901 first time testers in 2017 AZ had 4087 first time testers in 2018 Program Type Legend: The average pass rates were: The average pass rates were: Independent, LTC Facility, High School, College Written 86% and Skills 81% Written 87% and Skills 80% Initial 2017 2018 Program Program Program Name Approval Number of Written Skills Number of Written Skills Code Code Date Testers Testers Academy for Cargiving Excellence Tucson, AZ 3030 7/23/2018 No Testers in 2017 3030 No Testers in 2018 Phone: 520-338-4402 Accord Healthcare Institute * Phoenix, AZ 8912 3/30/2010 120 75% 85% 8912 109 77% 82% Phone: 602-714-3439 Voluntary Consent for Probation 11/18/16 Arizona Medical Training Institute* Mesa, AZ 4167 3/23/2000 636 96% 94% 4167 527 92% 89% Phone: 480-835-7679 Arizona Western College Yuma, AZ 4101 11/10/2010 110 93% 85% 4101 110 98% 93% Phone: 928-344-7554 Arizona Western College, Parker/La Paz Parker, AZ 4104 1/1/2002 No Testers in 2017 4104 No Testers in 2018 Phone: 928-344-7554 AZ Nursing Careers, Inc. -

Yavapai College Community Benefits Statements. INSTITUTION Yavapai Coll., Prescott, AZ

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 482 500 JC 030 664 AUTHOR Salmon, Robert O.; Wing, Barbara; Fairchilds, Angie; Quinley, John TITLE Yavapai College Community Benefits Statements. INSTITUTION Yavapai Coll., Prescott, AZ. PUB DATE 2003-05-00 NOTE 257p.; Prepared by the Office of Instruction. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Community Colleges; Educational Research; Graduate Surveys; School Statistics; *School Surveys; Schools; Student Attitudes; *Student Characteristics; Student Surveys; *Two Year Colleges IDENTIFIERS *Yavapai College AZ ABSTRACT The Yavapai College Districts Board and members of Yavapai College administration and staff developed this report. It contains 12 statements that compromise the core outcomes of the Yavapai College Mission. The extent to which each college addresses these outcomes is then reflected in a series of indicators that are tied to the individual Community Benefits Statements (CBS). Some of the major CBS are student satisfaction, graduate satisfaction with preparation for transfer and preparation for career development, access to benefits of partnership, and the capacity to access information, expertise, technology assistance, and resources needed to be competitive in a global economy. Some of the major findings of the study are as follows:(1) over three fourths of Yavapai College students were satisfied or very satisfied with how well they were prepared for transfer;(2) the number of occupational degrees awarded has decreased; and (3) students expressed high satisfaction with college services. The study concludes that more detailed studies centered on any of the indicators and CBS would be beneficial to aid in better understanding the college's achievement, the achievement of individual programs, and creating specific subsequent action plans. -

Nursing Assistant Programs Thursday, November 12, 2020 1:00Pm

AZBN Monthly Education Meeting with Arizona Nursing Assistant Programs Thursday, November 12, 2020 1:00pm Summary ➢ Welcome The meeting began at 1:01pm with Cindy George facilitating the call. ➢ Roll Call: Alhambra High School Arizona Career institute Arizona Medical Training Institute Cochise College Coconino Community College Combs High School Department of Education (Aden Ramirez) East Valley Institute of Technology Facets Healthcare Gateway Community College Gila Community College/Eastern Arizona College - Gila Pueblo Campus Meadows of Northern Arizona Mesa Community College - MAIN Mesa Community College - Red Mountain Campus Northland Pioneer College Pierson High School Pima County JTED Pima Medical Institute Saguaro High School Star Canyon School of Nursing Valley Vocational Academy West-Mec Yavapai College Yuma Union ➢ Department of Education Update for High Schools (Aden Ramirez) Aden gave an update on high schools amid the COVID pandemic. He stated that each high school makes decisions within their local district, new guidelines for each school is up to the individual school/district. Aden has started monitoring each high school, reach out if you have any questions. Aden will also be sending out a high school summary after each CNA meeting. Aden and Cindy will be working to get a quarterly meeting for the high schools in the new year. ➢ Renewal packets- Numbering of pages and ranges (Cindy) Please make sure you number your pages straight through starting with #1 and then all the way through. Also, please do not put ranges on where to find things, just give page numbers, if it is more than one place, just page numbers. I will be sending back any renewal submissions that are not numbered correctly or have ranges in them. -

EAC 2013-2014 Catalog

EASTERN ARIZONA COLLEGE Arizona’s oldest and most unexpected community college 2013-2014 academic catalog table of contents Introduction . 2 Academic Regulations . .40 Academic Calendar . 4 Graduation . .46 Directories . 6 General Education . .47 Thatcher Campus Map . 8 Transfer Partnerships . .50 Gila County Campus Information . 18 Curricula . .52 Enrollment . .20 Course Descriptions . 116 Tuition and Fees . .22 Disclosures . 175 Housing and Dining Facilities . 24 Residency . 179 contents Financial Aid and Scholarships . .25 Security and Safety . 181 Student Services . .34 Index . .185 Student Code of Conduct . .36 official document notice EASTERN ARIZONA COLLEGE CATALOGS and class schedules are available as both printed and electronic documents published on the Internet. Printed documents are correct as of the date of preparation. The Internet versions are updated as needed and are the College’s official publications. All who use the catalogs or class schedules are advised that when taking action or making plans based on published information, the Internet versions should be relied upon as the official documents. Public access to Internet-based College publications is available at all EAC administrative sites or at www.eac.edu. This catalog has been prepared to give you information on the programs and courses available at Eastern Arizona College and to answer questions you may have about official policies, procedures, and regulations. To arrange a visit or to ask any questions, please contact us at: Eastern Arizona College Thatcher, AZ 85552-0769 (928) 428-8272 1-800-678-3808 FAX: (928) 428-2578 E-mail: [email protected] Students needing language assistance to interpret information Estudiantes que necesitan ayuda en interpretar la información presented in this catalog should contact EAC’s Counseling contenida en este catálogo deben de ponerse en contacto con el Department for assistance. -

Arizona AHEC Annual Report, 2020

Annual Report 2020 Arizona AHEC Program Mission Statement: To enhance access to quality health care, particularly primary and preventive care, by improving the supply and distribution of health care professionals through academic community educational partnerships in rural and urban medically underserved areas. AzAHEC PROGRAM HIGHLIGHTS In FY 2019-20, 11,368 participated in the following activities: Rural & Urban Underserved Health Professions Pre-College (K-16) Health Career Preparation Trainee Field Experiences Programs in Rural and Urban Underserved Areas: From July 1, 2019 to June 30, 2020, the AzAHEC Program 6,198 participants. supported the following unduplicated field experiences in Participants in K-16 Health Career Preparation Programs AzAHEC Regional Centers, Rural Health Professions Programs included 1,932 K-16 students in 60 health careers clubs, and Residency Programs for nearly 210,000 contact hours: inclusive of academic year programs, summer programs at the University of Arizona (Frontera, Med-Start and BLAIS- # of # of Field Academic Discipline/Program Trainees Experiences ER), and summer programs at AzAHEC Regional Centers. Medical Residency 38 50 A total of 4,266 students and adults (parents, teachers and others) participated in 80 other health career events, Pharmacy School 89 160 including health career fairs. Other Undergraduate Health-related 46 55 Disciplines Nursing or Medical Assistant 203 203 Health Professions Continuing Education: 4,046 participants. Dentistry and Dental Hygiene 32 33 Participants at 198 continuing education events included Nurse Practitioner 115 206 4,046 physicians, dentists, public and allied health profes- Graduate - Psychology 1 1 sionals, pharmacists, nurse practitioners, registered nurses Public Health 202 229 and physician assistants. -

Arizona College College &&

ArizonaArizona College College && CC AA RR EE EE RR GG UU A Publication of the Arizona Commission II for Postsecondary Education DD Visit the guide online at http://www.azhighered.gov EE 2011-2012 35th Edition State of Arizona The Honorable Janice K. Brewer Governor Arizona Commission for Postsecondary Education Commissioners Dr. Seth Balogh (Chair) Dr. Tom Anderes (Ex-Officio) Dr. Debra Duvall Dr. Eugene Garcia Dr. Eldon Hastings Michael Hawksworth Melissa Holdaway Catherine Koluch Teena Olszewski Dr. William Pepicello Dr. Kathy Player Dr. Anna Solley Teri Stanfill (Ex-Officio) Dr. Manuel Valenzuela Chuck Wilson Dr. April L. Osborn, Executive Director Judi Sloan, Editor Commission Office 2020 North Central Avenue, Suite 650 Phoenix, Arizona 85004 Telephone (602) 258-2435 Fax (602) 258-2483 E-mail: [email protected] 2011 - 2012, 35th Edition Arizona College and Career Guide 2011 - 2012 © Visit the Commission’s web site at www.azhighered.gov for the digital version of this publication INDEX Welcome---------------------------------------------------------------1 Accreditation ------------------------------------------------------------2 Notice-----------------------------------------------------------------4 Financial Aid-------------------------------------------------------------4 Alphabetical Listing of Institutions----------------------------------------------6 Postsecondary Sector Listing of Institutions --------------------------------------9 Listing of Programs of Study or Majors -----------------------------------------13 ArizonaStateUniversity----------------------------------------------------27 -

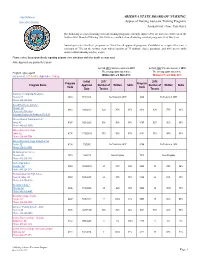

ARIZONA STATE BOARD of NURSING Executive Director Approved Nursing Assistant Training Programs Annual First -Time Pass Rates

Joey Ridenour ARIZONA STATE BOARD OF NURSING Executive Director Approved Nursing Assistant Training Programs Annual First -Time Pass Rates The following is a list of nursing assistant training programs currently approved by the Executive Director of the Arizona State Board of Nursing. Site visits are conducted on all nursing assistant programs every two years. Annual pass rates for these programs are listed for all approved programs. Candidates are required to score a minimum of 75% on the written exam which consists of 75 multiple choice questions, and 80% on the skills exam (without missing any key steps). Please contact the program directly regarding program costs, start dates and other details you may need. Note: Approvals are granted for 2 years AZ had 4216 first time testers in 2016 AZ had 3901 first time testers in 2017 Program Type Legend: The average pass rates were: The average pass rates were: Independent, LTC Facility, High School, College Written 86% and Skills 79% Written 86% and Skills 81% Initial 2016 2017 Program Program Program Name Approval Number of Written Skills Number of Written Skills Code Code Date Testers Testers A Plus Healthcare Training * Phoenix, AZ 3200 3/2/2017 No Testers in 2016 3200 1 100% 100% Phone: 480-376-2590 Academic Training AZ * (fka K’s Training & Learning Center) Glendale, AZ 9208 4/14/2011 37 86% 46% 9208 48 81% 94% Phone: 602-350-5154 Accord Healthcare Institute * Phoenix, AZ 8912 3/30/2010 212 72% 83% 8912 120 75% 85% Phone: 602-714-3439 Voluntary Consent for Probation 11/18/16 Arizona CNA -

For Older Adults, Caregivers, and Their Families in Pinal and Gila Counties

For older adults, caregivers, and their families in Pinal and Gila counties Pinal-Gila Council for Senior Citizens 8969 W. McCartney Road Casa Grande, AZ 85194 (520) 836-2758 or 1 (800) 293-9393 www.pgcsc.org Funding support for this Guide provided by: Pinal-Gila Council for Senior Citizens, Area Agency on Aging, Region V DES, Division of Aging and Adult Services Older Americans Act AARP Updated July 2020 A Message for Older Adults, Caregivers and Their Families Knowing where to look for resources to care for oneself, family members and friends can be a daunting task. Pinal-Gila Council for Senior Citizens has compiled Senior Connections Resource Guide to serve as a foundational guide in your quest for information. In addition to a listing of community resources, this guide contains an overview of Area Agencies on Aging and further information and referral resources. Also, the Appendix contains a listing of national organization websites, must-have documents for caregivers, and emergency numbers. Pinal-Gila Council for Senior Citizens is committed to providing assistance and information, as well as continuing to advocate on your behalf. We are dedicated to our vision and mission to meet the ever changing dynamic needs of those older adults and caregivers that we are here to serve. If you are a caregiver, you are one of over 804,000 caregivers in Arizona. If you are aged 60 or older, you are one of over 1,232,000 residents in Arizona’s fastest growing age group. So please, remember that you are not alone. We gratefully acknowledge the continued support of AARP Arizona, which also provided the initial funding for our resource guide specifically for older adults and caregivers in Pinal and Gila counties.