07884-80045.Pdf (248.55

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clones Stick Together

TVhome The Daily Home April 12 - 18, 2015 Clones Stick Together Sarah (Tatiana Maslany) is on a mission to find the 000208858R1 truth about the clones on season three of “Orphan Black,” premiering Saturday at 8 p.m. on BBC America. The Future of Banking? We’ve Got A 167 Year Head Start. You can now deposit checks directly from your smartphone by using FNB’s Mobile App for iPhones and Android devices. No more hurrying to the bank; handle your deposits from virtually anywhere with the Mobile Remote Deposit option available in our Mobile App today. (256) 362-2334 | www.fnbtalladega.com Some products or services have a fee or require enrollment and approval. Some restrictions may apply. Please visit your nearest branch for details. 000209980r1 2 THE DAILY HOME / TV HOME Sun., April 12, 2015 — Sat., April 18, 2015 DISH AT&T DIRECTV CABLE CHARTER CHARTER PELL CITY PELL ANNISTON CABLE ONE CABLE TALLADEGA SYLACAUGA BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM CONVERSION CABLE COOSA SPORTS WBRC 6 6 7 7 6 6 6 6 AUTO RACING Friday WBIQ 10 4 10 10 10 10 6 p.m. FS1 St. John’s Red Storm at Drag Racing WCIQ 7 10 4 Creighton Blue Jays (Live) WVTM 13 13 5 5 13 13 13 13 Sunday Saturday WTTO 21 8 9 9 8 21 21 21 7 p.m. ESPN2 Summitracing.com 12 p.m. ESPN2 Vanderbilt Com- WUOA 23 14 6 6 23 23 23 NHRA Nationals from The Strip at modores at South Carolina WEAC 24 24 Las Vegas Motor Speedway in Las Gamecocks (Live) WJSU 40 4 4 40 Vegas (Taped) 2 p.m. -

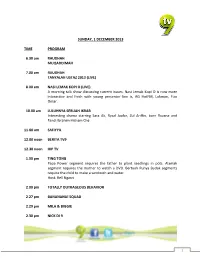

1 SUNDAY, 1 DECEMBER 2013 TIME PROGRAM 6.30 Am

SUNDAY, 1 DECEMBER 2013 TIME PROGRAM 6.30 am RAUDHAH MUQADDIMAH 7.00 am RAUDHAH TANYALAH USTAZ 2013 (LIVE) 8.00 am NASI LEMAK KOPI O (LIVE) A morning talk show discussing current issues. Nasi Lemak Kopi O is now more interactive and fresh with young presenter line is, AG HotFM, Lokman, Fizo Omar. 10.00 am LULUHNYA SEBUAH IKRAR Interesting drama starring Sara Ali, Ryzal Jaafar, Zul Ariffin, born Ruzana and Fandi Ibrahim Hisham Che 11.00 am SAFIYYA 12.00 noon BERITA TV9 12.30 noon HIP TV 1.00 pm TING TONG Papa Power segment requires the father to plant seedlings in pots. Alamak segment requires the mother to watch a DVD. Bertuah Punya Budak segments require the child to make a sandwich and water. Host: Bell Ngasri 2.00 pm TOTALLY OUTRAGEOUS BEHAVIOR 2.27 pm BANANANA! SQUAD 2.29 pm MILA & BIGGIE 2.30 pm NICK DI 9 1 TEAM UMIZOOMI 3.00 pm NICK DI 9 DORA THE EXPLORER 3.30 pm NICK DI 9 ADVENTURES OF JIMMY NEUTRONS 4.00 pm NICK DI 9 PLANET SHEEN 4.30 pm NICK DI 9 AVATAR THE LEGEND OF AANG 5.00 pm NICK DI 9 SPONGEBOB SQUAREPANTS 5.28 pm BANANANA! SQUAD 5.30 pm BOLA KAMPUNG THE MOVIE Amanda is a princess who comes from the virtual world of a game called "Kingdom Hill '. She was sent to the village to find Pewira Suria, the savior who can end the current crisis. Cast: Harris Alif, Aizat Amdan, Harun Salim Bachik, Steve Bone, Ezlynn 7.30 pm SWITCH OFF 2 The Award Winning game show returns with a new twist! Hosted by Rockstar, Radhi OAG, and the game challenges bands with a mission to save their band members from the Mysterious House in the Woods. -

Bolton's Budget Talks Collapse

J u N anrbpBtpr Hrralb Newsstand Price: 35 Cents Weekend Edition, Saturday, June 23,1990 Manchester — A City of Village Charm Bolton’s budget talks collapse TNT, CASE fail to come to terms.. .page 4 O \ 5 - n II ' 4 ^ n ^ H 5 Iran death S i z m toll tops O "D 36,1 Q -n m rn w State group S o sends aid..page 2 s > > I - 3 3 CO 3 3 > > H ■ u ^ / Gas rate hike requested; 9.8 percent > 1 4 MONTH*MOK Coventry will be Judy Hartling/Manchealsr Herald BUBBLING AND STRUGGLING — Gynamarie Dionne, age 4, tries for a drink from the affected.. .page 8 fountain at Manchester’s Center F*ark. Her father, Scott, is in the background. Moments later, he gave her a lift. ,...___ 1 9 9 0 J u p ' ^ ‘Robin HUD .■ '• r ■4 given stiff (y* ■ • i r r ■ prison term 1 . I* By Alex Dominguez The Associated Press BALTIMORE “Robin HUD,” the former real estate agent who claimed she stole about $6 million from HUD to help the poor, was sentenced Friday to the maximum prison term of nearly four years. t The Associated Press U.S. District Judge Herbert Murray issued the 46- month sentence at the request of the agent, Marilyn Har rell, who federal officials said stole more from the government than any individual. “I will ask you for the maximum term because I DEATH AND SURVIVAL — A father, above, deserve it,” Harrell told the judge. “I have never said what I did was right. -

Nickelodeon Previews New Content Pipeline for 2014-2015 Season at Annual Upfront Presentation

Nickelodeon Previews New Content Pipeline for 2014-2015 Season at Annual Upfront Presentation Nick to Add 10 New Series to Schedule, with Content Spanning Every Genre, Every Platform Network Unveils Plans for Brand-New, Live Tent-Pole Event, Kids' Choice Sports 2014; Host/Executive Producer Michael Strahan Details Show Slated for 3Q 2014 Upfront Presentation Capped by Special Musical Performance from Five-Time Grammy Nominee Sara Bareilles NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Nickelodeon held its annual upfront presentation today at Jazz at Lincoln Center in New York City, where Nickelodeon Group President Cyma Zarghami detailed the network's biggest content pipeline ever: 10 new series across every genre, and for every platform—all tailor-made for the tastes of today's post-millennial generation of kids. Zarghami also announced plans for the forthcoming Nick Jr. App, featuring TV Everywhere capability, and the brand-new, live tent-pole event, Kids' Choice Sports—the first-ever expansion of the highly successful Kids' Choice Awards franchise. Nickelodeon's presentation was also punctuated by remarks from Viacom Chairman Philippe Dauman; an appearance by Kids' Choice Sports 2014 host and executive producer Michael Strahan; and a closing musical performance from five-time Grammy nominee Sara Bareilles. "Our mission has been to create and deliver funny content that will resonate with today's kids, and we are well-positioned to do that through our schedule of fresh hits, a deep pipeline of new series, tent-pole events, ratings momentum and innovation on all platforms," said Zarghami. "Nickelodeon is a magnet for creative people and projects, and we're incredibly excited about the new pool of talent we're bringing to our audience in front of and behind the camera." Nickelodeon has posted 13 straight months of year-over-year growth and reclaimed the top spot with kids in 4Q13. -

Kids Elect President Barack Obama the Winner in Nickelodeon's Kids Pick the President "Kids' Vote" National Poll

Kids Elect President Barack Obama The Winner In Nickelodeon's Kids Pick the President "Kids' Vote" National Poll More Than Half a Million Votes Cast NEW YORK, Oct. 22, 2012 /PRNewswire/ -- The kids of the United States have spoken and President Barack Obama has been elected the winner of Nickelodeon's 2012 Kids Pick the President "Kids' Vote." Since it began in 1988, kids have correctly picked the winner (in advance of the national election) five out of the last six times. More than half a million votes were cast in the network's online poll as part of Nickelodeon's Kids Pick the President initiative to build young citizens' awareness of, and involvement in, the election process. President Obama received 65% of the vote and former Governor Mitt Romney received 35%. In order to more closely replicate the actual election, and to ensure the results were more authentic, this year the voting was limited to one vote per electronic device. Kids were able to cast their votes online from Oct. 15 to Oct. 22. On Monday, Oct. 22, at 7:30 p.m. (ET/PT), Linda Ellerbee, the Emmy Award-winning host of Nickelodeon's Nick News, will announce the winner of the Kids Pick the President "Kids' Vote" on the network. "What politicians do definitely affects kids but for me, it's not about who wins," said Ellerbee. "It's about creating tomorrow's voters. Democracy takes work. We're the practice field." Leading up to the Kids Pick the President online vote, Nickelodeon aired two election-themed Nick News with Linda Ellerbee specials this year, which ranked as the series' highest-rated episodes for 2012 to date. -

Liminal Losers: Breakdowns and Breakthroughs in Reality Television's Biggest Hit

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 4-2013 Liminal Losers: Breakdowns and Breakthroughs in Reality Television's Biggest Hit Caitlin Rickert Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, and the Health Communication Commons Recommended Citation Rickert, Caitlin, "Liminal Losers: Breakdowns and Breakthroughs in Reality Television's Biggest Hit" (2013). Master's Theses. 136. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/136 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIMINAL LOSERS: BREAKDOWNS AND BREAKTHROUGHS IN REALITY TELEVISION’S BIGGEST HIT by Caitlin Rickert A Thesis submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts School of Communication Western Michigan University April 2013 Thesis Committee: Heather Addison, Ph. D., Chair Sandra Borden, Ph. D. Joseph Kayany, Ph. D. LIMINAL LOSERS: BREAKDOWNS AND BREAKTHROUGHS IN REALITY TELEVISION’S BIGGEST HIT Caitlin Rickert, M.A. Western Michigan University, 2013 This study explores how The Biggest Loser, a popular television reality program that features a weight-loss competition, reflects and magnifies established stereotypes about obese individuals. The show, which encourages contestants to lose weight at a rapid pace, constructs a broken/fixed dichotomy that oversimplifies the complex issues of obesity and health. My research is a semiotic analysis of the eleventh season of the program (2011), focusing on three pairs of contestants (or “couples” teams) that each represent a different level of commitment to the program’s values. -

68Th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS for Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016

EMBARGOED UNTIL 8:40AM PT ON JULY 14, 2016 68th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS For Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016 Los Angeles, CA, July 14, 2016– Nominations for the 68th Emmy® Awards were announced today by the Television Academy in a ceremony hosted by Television Academy Chairman and CEO Bruce Rosenblum along with Anthony Anderson from the ABC series black-ish and Lauren Graham from Parenthood and the upcoming Netflix revival, Gilmore Girls. "Television dominates the entertainment conversation and is enjoying the most spectacular run in its history with breakthrough creativity, emerging platforms and dynamic new opportunities for our industry's storytellers," said Rosenblum. “From favorites like Game of Thrones, Veep, and House of Cards to nominations newcomers like black-ish, Master of None, The Americans and Mr. Robot, television has never been more impactful in its storytelling, sheer breadth of series and quality of performances by an incredibly diverse array of talented performers. “The Television Academy is thrilled to once again honor the very best that television has to offer.” This year’s Drama and Comedy Series nominees include first-timers as well as returning programs to the Emmy competition: black-ish and Master of None are new in the Outstanding Comedy Series category, and Mr. Robot and The Americans in the Outstanding Drama Series competition. Additionally, both Veep and Game of Thrones return to vie for their second Emmy in Outstanding Comedy Series and Outstanding Drama Series respectively. While Game of Thrones again tallied the most nominations (23), limited series The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story and Fargo received 22 nominations and 18 nominations respectively. -

Brand Armani Jeans Celebry Tees Rochas Roberto Cavalli Capcho

Brand Armani Jeans Celebry Tees Rochas Roberto Cavalli Capcho Lady Million Just Over The Top Tommy Hilfiger puma TJ Maxx YEEZY Marc Jacobs British Knights ROSALIND BREITLING Polo Vicuna Morabito Loewe Alexander Wang Kenzo Redskins Little Marcel PIGUET Emu Affliction Bensimon valege Chanel Chance Swarovski RG512 ESET Omega palace Serge Pariente Alpinestars Bally Sven new balance Dolce & Gabbana Canada Goose thrasher Supreme Paco Rabanne Lacoste Remeehair Old Navy Gucci Fjallraven Zara Fendi allure bridals BLEU DE CHANEL LensCrafters Bill Blass new era Breguet Invictus 1 million Trussardi Le Coq Sportif Balenciaga CIBA VISION Kappa Alberta Ferretti miu miu Bottega Veneta 7 For All Mankind VERNEE Briston Olympea Adidas Scotch & Soda Cartier Emporio Armani Balmain Ralph Lauren Edwin Wallace H&M Kiss & Walk deus Chaumet NAKED (by URBAN DECAY) Benetton Aape paccbet Pantofola d'Oro Christian Louboutin vans Bon Bebe Ben Sherman Asfvlt Amaya Arzuaga bulgari Elecoom Rolex ASICS POLO VIDENG Zenith Babyliss Chanel Gabrielle Brian Atwood mcm Chloe Helvetica Mountain Pioneers Trez Bcbg Louis Vuitton Adriana Castro Versus (by Versace) Moschino Jack & Jones Ipanema NYX Helly Hansen Beretta Nars Lee stussy DEELUXE pigalle BOSE Skechers Moncler Japan Rags diamond supply co Tom Ford Alice And Olivia Geographical Norway Fifty Spicy Armani Exchange Roger Dubuis Enza Nucci lancel Aquascutum JBL Napapijri philipp plein Tory Burch Dior IWC Longchamp Rebecca Minkoff Birkenstock Manolo Blahnik Harley Davidson marlboro Kawasaki Bijan KYLIE anti social social club -

Alisa Blanter Design & Direction

EXPERIENCE Freelance | NYC, Boston Designer, 2001-present Worked both on and off site for various clients, including Sesame Workshop, Bath & Body Works, MIT, Nickelodeon, Magnolia Pictures, VIBE Vixen magazine, Segal Savad Design, Hearst Creative Group, and Teen Vogue. ALISA BLANTER Proverb | Boston DESIGN & DIRECTION Senior Art Director, 2016-present www.alisablanter.com Lead the creative team at Proverb, reporting to the Managing Partners. The role oversees the design of logos, websites, signage, collateral, packaging and all other brand supporting — assets for a wide variety of clients in industries, such as real estate, non-profit, health care, interior design, education, retail and the arts. Collaborates with strategy to create initial EDUCATION concepts and design directions. Recruits new designers, reviews and approves all design Massachusetts College of Art produced by the creative team. Graphic Design BFA with Departmental Honors Nickelodeon | NYC Art Director, 2014-2015 — Led a team of designers and freelance vendors to create diverse materials, including SKILLS style guides, logos, packaging and press kits. Managed brand implementation across multiple platforms. Collaborated with VP Creative to establish and provide creative Illustrator, Photoshop, InDesign, and design direction for Nick Jr. properties for internal and external stakeholders. Office, Keynote, Acrobat — Nickelodeon | NYC Associate Art Director, 2010-2014 LANGUAGES Collaborated with the Senior Art Director in establishing and providing the creative English, Russian -

First Lady Michelle Obama to Receive Nickelodeon's Big Help Award

First Lady Michelle Obama To Receive Nickelodeon's Big Help Award Award Kicks Off The Big Help "Millions On The Move" Pro-Social Campaign NEW YORK, March 25, 2010 /PRNewswire via COMTEX/ -- Nickelodeon will honor the First Lady of the United States, Michelle Obama, with the Big Help Award in a special presentation during Nickelodeon's 23rd Annual Kids' Choice Awards on Saturday, March 27. The Big HelpAward will pay tribute to the First Lady for her leadership in championing a healthy generation of kids and families through her recently launched Let's Move! initiative. The award recognizes those who seek to better the world, and whose significant impact on their community has inspired kids to do the same. "First Lady Michelle Obama has taken on one of this generation's most pressing concerns: the health and wellness of our nation's children," said Marva Smalls, Executive Vice President, Public Affairs and Chief of Staff, Nickelodeon/MTVN Kids and Family Group. "Her willingness to work hard, influence others and her dedication to improving the nation is inspiring, and we are proud to honor her for her commitment to empowering kids and families to address one of the most important issues of today." Launched in February 2010 by the First Lady to end the American epidemic of childhood obesity in a single generation, the nationwide Let's Move! campaign focuses on helping parents make healthier life choices for their families, providing healthier food in schools, encouraging kids to be more active and ensuring access to healthy, affordable food in every part of the country. -

NOMINEES for the 32Nd ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY

NOMINEES FOR THE 32 nd ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY ® AWARDS ANNOUNCED BY THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES Winners to be announced on September 26th at Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center Larry King to Receive Lifetime Achievement Award New York, N.Y. – July 18, 2011 (revised 8.24.11) – Nominations for the 32nd Annual News and Documentary Emmy ® Awards were announced today by the National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS). The News & Documentary Emmy® Awards will be presented on Monday, September 26 at a ceremony at Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center, located in the Time Warner Center in New York City. The event will be attended by more than 1,000 television and news media industry executives, news and documentary producers and journalists. Emmy ® Awards will be presented in 42 categories, including Breaking News, Investigative Reporting, Outstanding Interview, and Best Documentary, among others. This year’s prestigious Lifetime Achievement Award will be given to broadcasting legend and cable news icon Larry King. “Larry King is one of the most notable figures in the history of cable news, and the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences is delighted to present him with this year’s lifetime achievement award,” said Malachy Wienges, Chairman, NATAS. “Over the course of his career Larry King has interviewed an enormous number of public figures on a remarkable range of topics. In his 25 years at CNN he helped build an audience for cable news and hosted more than a few history making broadcasts. -

Wild Kratts®: Ocean Adventure! Now Open!

Summer/Fall 2019 News and Events for Members, Donors, and Friends WILD KRATTS®: OCEAN ADVENTURE! NOW OPEN! The Strong Unearths Rare Atari Footage through Digital Preservation Efforts While digitizing U-Matic tapes (an analog videocassette format) in The Strong’s Atari Coin-Op Division collection, museum curators and library staff recently discovered a wide range of never-before-seen footage—including video of Atari’s offices and manufacturing lines, its arcade cabinet construction practices, and company-wide staff celebrations. The footage also includes gameplay of many of Atari’s popular titles, as well as video concepts for games never released. The video collection offers an unprecedented look at the inner-workings of Atari at its height at a time that it helped to lay the groundwork for the modern video game industry. The museum’s digitization efforts are made possible, in part, by a grant from the Rochester Regional Library Council. Screenshot from unearthed Atari footage. Fairy Magic Storybook Summer Through October 31 Weekdays, July 8–August 30 • 11 a.m.–3 p.m. Take a magical stroll through Spend the summer with your favorite storybook characters! Listen to Dancing Wings Butterfly story readings at 2 p.m., take pictures with featured characters, and Garden. Listen to enchanting enjoy activities based on their stories. music as you walk among hundreds of butterflies and July 8–12: How Do Dinosaurs…? whimsical flowers, including Meet the Dinosaur from Jane Yolen’s popular series, orchids and begonias, and recreate story scenes with toy dinosaurs, and make check out fairy house doors a dinosaur headband and feet.