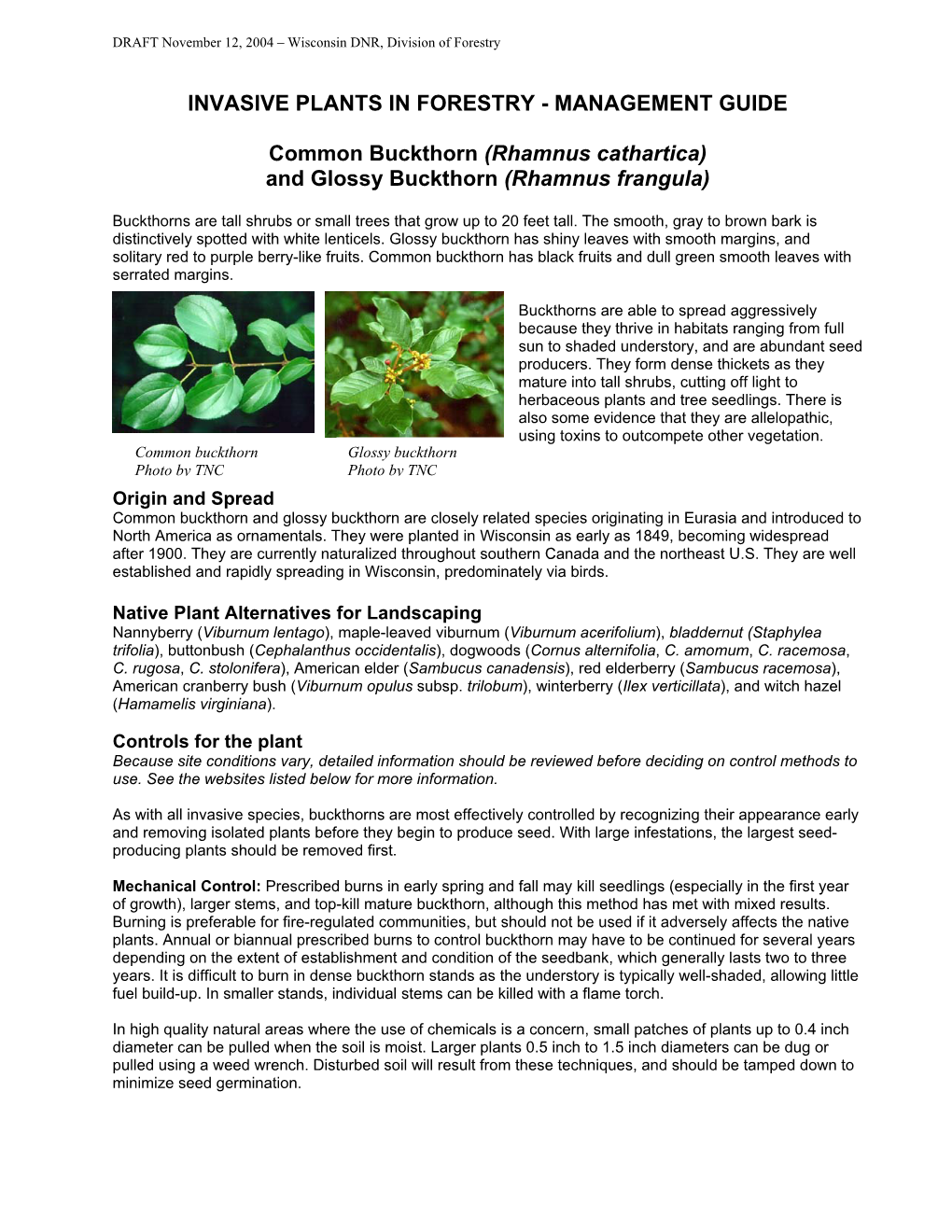

Eurasian Buckthorn (Rhamnus Cathartica)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossy Buckthorn Rhamnusoriental Frangula Bittersweet / Frangula Alnus Control Guidelines Fact Sheet

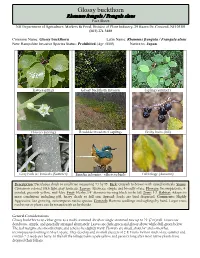

Glossy buckthorn Oriental bittersweet Rhamnus frangula / Frangula alnus Control Guidelines Fact Sheet NH Department of Agriculture, Markets & Food, Division of Plant Industry, 29 Hazen Dr, Concord, NH 03301 (603) 271-3488 Common Name: Glossy buckthorn Latin Name: Rhamnus frangula / Frangula alnus New Hampshire Invasive Species Status: Prohibited (Agr 3800) Native to: Japan leaves (spring) Glossy buckthorn invasion Sapling (summer) Flowers (spring) Roadside invasion of saplings Fleshy fruits (fall) Gray bark w/ lenticels (Summer) Emodin in berries - effects to birds Fall foliage (Autumn) Description: Deciduous shrub or small tree measuring 20' by 15'. Bark: Grayish to brown with raised lenticels. Stems: Cinnamon colored with light gray lenticels. Leaves: Alternate, simple and broadly ovate. Flowers: Inconspicuous, 4- petaled, greenish-yellow, mid-May. Fruit: Fleshy, 1/4” diameter turning black in the fall. Zone: 3-7. Habitat: Adapts to most conditions including pH, heavy shade to full sun. Spread: Seeds are bird dispersed. Comments: Highly Aggressive, fast growing, outcompetes native species. Controls: Remove seedlings and saplings by hand. Larger trees can be cut or plants can be treated with an herbicide. General Considerations Glossy buckthorn can either grow as a multi-stemmed shrub or single-stemmed tree up to 23’ (7 m) tall. Leaves are deciduous, simple, and generally arranged alternately. Leaves are dark-green and glossy above while dull-green below. The leaf margins are smooth/entire and tend to be slightly wavy. Flowers are small, about ¼” and somewhat inconspicuous forming in May to June. They develop and in small clusters of 2-8. Fruits form in mid to late summer and contain 2-3 seeds per berry. -

Biology of a Rust Fungus Infecting Rhamnus Frangula and Phalaris Arundinacea

Biology of a rust fungus infecting Rhamnus frangula and Phalaris arundinacea Yue Jin USDA-ARS Cereal Disease Laboratory University of Minnesota St. Paul, MN Reed canarygrass (Phalaris arundinacea) Nature Center, Roseville, MN Reed canarygrass (Phalaris arundinacea) and glossy buckthorn (Rhamnus frangula) From “Flora of Wisconsin” Ranked Order of Terrestrial Invasive Plants That Threaten MN -Minnesota Terrestrial Invasive Plants and Pests Center Puccinia coronata var. hordei Jin & Steff. ✧ Unique spore morphology: ✧ Cycles between Rhamnus cathartica and grasses in Triticeae: o Hordeum spp. o Secale spp. o Triticum spp. o Elymus spp. ✧ Other accessory hosts: o Bromus tectorum o Poa spp. o Phalaris arundinacea Rust infection on Rhamnus frangula Central Park Nature Center, Roseville, MN June 2017 Heavy infections on Rhamnus frangula, but not on Rh. cathartica Uredinia formed on Phalaris arundinacea soon after mature aecia released aeiospores from infected Rhamnus frangula Life cycle of Puccinia coronata from Nazaredno et al. 2018, Molecular Plant Path. 19:1047 Puccinia coronata: a species complex Forms Telial host Aecial host (var., f. sp.) (primanry host) (alternate host) avenae Oat, grasses in Avenaceae Rhamnus cathartica lolii Lolium spp. Rh. cathartica festucae Fescuta spp. Rh. cathartica hoci Hocus spp. Rh. cathartica agronstis Agrostis alba Rh. cathartica hordei barley, rye, grasses in triticeae Rh. cathartica bromi Bromus inermis Rh. cathartica calamagrostis Calamagrostis canadensis Rh. alnifolia ? Phalaris arundinacea Rh. frangula Pathogenicity test on cereal crop species using aeciospores from Rhamnus frangula Cereal species Genotypes Response Oats 55 Immune Barley 52 Immune Wheat 40 Immune Rye 6 Immune * Conclusion: not a pathogen of cereal crops Pathogenicity test on grasses Grass species Genotypes Response Phalaris arundinacea 12 Susceptible Ph. -

Seed Dormancy and Consequences for Direct Tree Seeding H

Seed dormancy and consequences for direct tree seeding H. Frochot, Philippe Balandier, A. Sourisseau To cite this version: H. Frochot, Philippe Balandier, A. Sourisseau. Seed dormancy and consequences for direct tree seed- ing. Final COST E47 conference Forest vegetation management towards environmental sustainability, May 2009, Vejle, Denmark. p. 43 - p. 45. hal-00468732 HAL Id: hal-00468732 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00468732 Submitted on 31 Mar 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Forest Vegetation Management – towards environmental sustainability, N.S. Bentsen (Ed.), Proccedings from the final COST E47 Conference, Vejle, Denmark, 2009/05/5-7, Forest and Landscape Working Papers n° 35-2009, 43-45. Seed dormancy and consequences for direct tree seeding Henri Frochot1), Philippe Balandier2,3), Agnès Sourisseau4) 1) INRA, UMR1092 LERFOB, F-54280 Champenoux, France, [email protected]; [email protected] 2) Cemagref, UR EFNO, Nogent sur Vernisson, France 3) INRA, UMR547 PIAF, Clermont-Ferrand, France 4) Independent Landscaper, Paris, France Key words Afforestation, direct seeding, dormancy, seed, tree Introduction Whereas direct tree seeding was probably used extensively in France in the past, it is currently only employed for the reforestation of Pinus pinaster and some species with big seeds such as oak. -

Frangula Paruensis, a New Name for Rhamnus Longipes Steyermark (Rhamnaceae)

FRANGULA PARUENSIS, A NEW NAME FOR RHAMNUS LONGIPES STEYERMARK (RHAMNACEAE) GERARDO A. AYMARD C.1, 2 Abstract. The new name Frangula paruensis (Rhamnaceae) is proposed to replace the illegitimate homonym Rhamnus longipes Steyermark (1988). Chorological, taxonomic, biogeographical, and habitat notes about this taxon also are provided. Resumen. Se propone Frangula paruensis (Rhamnaceae) como un nuevo nombre para reemplazar el homónimo ilegítimo Rhamnus longipes Steyermark (1988). Se incluye información corológica, taxonómica, biogeográfica, y de hábitats acerca de la especie. Keywords: Frangula, Rhamnus, Rhamnaceae, Parú Massif, Tepuis flora, Venezuela Rhamnus L. and Frangula Miller (Rhamnaceae) have Frangula paruensis is a shrub, ca. 2 m tall, with leaves ca. 150 and ca. 50 species, respectively (Pool, 2013, 2015). ovate, or oblong-ovate, margin subrevolute, repand- These taxa are widely distributed around the world but are crenulate, a slightly elevated tertiary venation on the lower absent in Madagascar, Australia, and Polynesia (Medan and surface, and mature fruiting peduncle and pedicels 1–1.5 Schirarend, 2004). According to Grubov (1949), Kartesz cm long, and fruiting calyx lobes triangular-lanceolate and Gandhi (1994), Bolmgren and Oxelman (2004), and (two main features to separate Frangula from Rhamnus). Pool (2013) the recognition of Frangula is well supported. This species is endemic to the open, rocky savannas On the basis of historical and recent molecular work the on tepui slopes and summits at ca. 2000 m (Steyermark genus is characterized by several remarkable features. Pool and Berry, 2004). This Venezuelan taxon was described (2013: 448, table 1) summarized 11 features to separate the as Rhamnus longipes by Steyermark (1988), without two genera. -

Rhamnaceae) Jürgen Kellermanna,B

Swainsona 33: 43–50 (2020) © 2020 Board of the Botanic Gardens & State Herbarium (Adelaide, South Australia) Nomenclatural notes and typifications in Australian species of Paliureae (Rhamnaceae) Jürgen Kellermanna,b a State Herbarium of South Australia, GPO Box 1047, Adelaide, South Australia 5001 Email: [email protected] b The University of Adelaide, School of Biological Sciences, Adelaide, South Australia 5005 Abstract: The nomenclature of the four species of Ziziphus Mill. and the one species of Hovenia Thunb. occurring in Australia is reviewed, including the role of the Hermann Herbarium for the typification of Z. oenopolia (L.) Mill. and Z. mauritiana Lam. Lectotypes are chosen for Z. quadrilocularis F.Muell. and Z. timoriensis DC. A key to species is provided, as well as illustrations for Z. oenopolia, Z. quadrilocularis and H. dulcis Thunb. Keywords: Nomenclature, typification, Hovenia, Ziziphus, Rhamnaceae, Paliureae, Paul Hermann, Carolus Linnaeus, Henry Trimen, Australia Introduction last worldwide overview of the genus was published by Suessenguth (1953). Since then, only regional Rhamnaceae tribe Paliureae Reissek ex Endl. was treatments and revisions have been published, most reinstated by Richardson et al. (2000b), after the first notably by Johnston (1963, 1964, 1972), Bhandari & molecular analysis of the family (Richardson et al. Bhansali (2000), Chen & Schirarend (2007) and Cahen 2000a). It consists of three genera, Hovenia Thunb., et al. (in press). For Australia, the genus as a whole was Paliurus Tourn. ex Mill. and Ziziphus Mill., which last reviewed by Bentham (1863), with subsequent until then were assigned to the tribes Rhamneae regional treatments by Wheeler (1992) and Rye (1997) Horan. -

(GISD) 2021. Species Profile Ziziphus Mauritiana. Availab

FULL ACCOUNT FOR: Ziziphus mauritiana Ziziphus mauritiana System: Terrestrial Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Plantae Magnoliophyta Magnoliopsida Rhamnales Rhamnaceae Common name appeldam (English, Dutch West Indies), baher (English, Fiji), bahir (English, Fiji), baer (English, Fiji), jujube (English, Guam), manzanita (English, Guam), manzanas (English, Guam), jujubier (French), Chinese date (English), Chinese apple (English), Indian jujube (English), Indian plum (English), Indian cherry (English), Malay jujube (English), coolie plum (English, Jamaica), crabapple (English, Jamaica), dunk (English, Barbados), mangustine (English, Barbados), dunks (English, Trinidad), dunks (English, Tropical Africa), Chinee apple (English, Queensland, Australia), ponsigne (English, Venezuela), yuyubo (English, Venezuela), aprin (English, Puerto Rico), yuyubi (English, Puerto Rico), perita haitiana (English, Dominican Republic), pomme malcadi (French, West Indies), pomme surette (French, West Indies), petit pomme (French, West Indies), liane croc chien (French, West Indies), gingeolier (French, West Indies), dindoulier (French, West Indies), manzana (apple) (English, Philippines), manzanita (little apple) (English, Philippines), bedara (English, Malaya), widara (English, Indonesia), widara (English, Surinam), phutsa (English, Thailand), ma-tan (English, Thailand), putrea (English, Cambodia), tao (English, Vietnam), tao nhuc (English, Vietnam), ber (English, India), bor (English, India) Synonym Ziziphus jujuba , (L.) Lam., non P. Mill. Rhamnus mauritiana -

NRM Plan Italian Buckthorn (Rhamnus Alaternus) CONTACT Reducing Its Impact in the Northern and Yorke NRM Region

Government of South Australia Northern and Yorke Natural FACT SHEET NO. 1.020 Resources Management Board June 2011 NRM Plan Italian buckthorn (Rhamnus alaternus) CONTACT Reducing its impact in the Northern and Yorke NRM Region Main Office Description of this weed Northern and Yorke NRM Board Buckthorn is a 3-5 metre tall small shrub PO Box 175 with bright green leathery leaves which 41-49 Eyre Road are lance-oval shape, with finely serrated Crystal Brook SA 5523 margins. The leaf’s upper surface is bright Ph: (08) 8636 2361 green, with the underside being paler Fx: (08) 8636 2371 in colour. www.nynrm.sa.gov.au The stems are smooth, not thorny as its common name suggests. Flowers are small, 3-4mm in diameter, with 5 petals and are yellow-green in colour. Flowering occurs in winter to early spring. Fruits are round, egg-shaped berries, smooth, 5-7mm long, red ripening to black. Buckthorn is generally found in areas receiving greater than 500mm of rain. Why is it a weed and what is the impact? Buckthorn was introduced to Australia as a garden plant and has escaped into Buckthorn is spread by birds eating the the bush. It is a hardy plant that will fruit and dispersing the seeds. Foxes and grow in a variety of soil types including possums also have the potential to spread riparian environments, sand dunes and the seeds. It suckers freely from a base escarpments. It tolerates full sun, cold and or roots, especially from inappropriately seasonal dry spells. dumped garden waste. -

Rhamnaceae Buckthorn

Rhamnus spp. Family: Rhamnaceae Buckthorn The genus Rhamnus contains over 100 species native to: North America [5], the rest from the north temperate regions, South America and South Africa. Many non-native species have been naturalized in the US. The name rhamnus is an ancient Greek name. Rhamnus alaternus-Mediterranean Buckthorn (Europe) Rhamnus alpinus-Alpine Buckthorn (Europe) Rhamnus betulifolia-Birchleaf Buckthorn Rhamnus californica-California Buckthorn , California Coffeeberry, Coast Coffeeberry, Coffeeberry, Pigeonberry, Sierra Coffeeberry Rhamnus caroliniana-Alder Buckthorn, Birch Bog, Brittlewood, Buckthorn-tree, Carolina Buckthorn , Elbow-brush, Indian Cherry, Pale-cat-wood, Polecat-tree, Polecatwood, Stinkberry, Stink Cherry, Stinkwood, Tree Buckthorn, Yellow Buckthorn, Yellowwood Rhamnus catharticus-Common Buckthorn, European Buckthorn , European Waythorn, Purgin Buckthorn Rhamnus crocea-California Redberry, Coffeeberry, Evergreen Buckthorn, Great Redberry Buckthorn, Hollyleaf Buckthorn , Island Buckthorn, Island Redberry Buckthorn, Redberry, Redberry Buckthorn Rhamnus frangula-(Europe) Alder Buckthorn, Glossy Buckthorn Rhamnus purshiana*-Bayberry, Bearberry, Bearwood, Bitterbark, Bitterboom, Bittertrad, Buckthorn Cascara, California Coffee, Cascara, Cascara Buckthorn , Cascara Sagrada, Chitam, Chittam, Chittern, Chittim, Coffeeberry, Coffeebush, Coffeetree, Oregon Bearwood, Pigeonberry, Shittimwood, Wahoo, Western Coffee, Wild Cherry, Wild Coffee, Wild Coffeebush, Yellow-wood Rhamnus zeyheri-(Africa) Pink Ivory, Red Ivorywood *commercial American species The following is for Cascara Buckthorn: Distribution The Pacific Coast region from British Columbia (incl. Vancouver Island), south to Washington, Oregon and northern California in Coast Ranges and the Sierra Nevada. Also in the Rocky Mountain region of British Columbia, Washington Idaho and Montana. The Tree Cascara Buckthorn grows in bottom lands, but can be found along fence rows and roadsides. It grows scattered among Douglas fir, maples, western redcedar and hemlock. -

Flora Mediterranea 26

FLORA MEDITERRANEA 26 Published under the auspices of OPTIMA by the Herbarium Mediterraneum Panormitanum Palermo – 2016 FLORA MEDITERRANEA Edited on behalf of the International Foundation pro Herbario Mediterraneo by Francesco M. Raimondo, Werner Greuter & Gianniantonio Domina Editorial board G. Domina (Palermo), F. Garbari (Pisa), W. Greuter (Berlin), S. L. Jury (Reading), G. Kamari (Patras), P. Mazzola (Palermo), S. Pignatti (Roma), F. M. Raimondo (Palermo), C. Salmeri (Palermo), B. Valdés (Sevilla), G. Venturella (Palermo). Advisory Committee P. V. Arrigoni (Firenze) P. Küpfer (Neuchatel) H. M. Burdet (Genève) J. Mathez (Montpellier) A. Carapezza (Palermo) G. Moggi (Firenze) C. D. K. Cook (Zurich) E. Nardi (Firenze) R. Courtecuisse (Lille) P. L. Nimis (Trieste) V. Demoulin (Liège) D. Phitos (Patras) F. Ehrendorfer (Wien) L. Poldini (Trieste) M. Erben (Munchen) R. M. Ros Espín (Murcia) G. Giaccone (Catania) A. Strid (Copenhagen) V. H. Heywood (Reading) B. Zimmer (Berlin) Editorial Office Editorial assistance: A. M. Mannino Editorial secretariat: V. Spadaro & P. Campisi Layout & Tecnical editing: E. Di Gristina & F. La Sorte Design: V. Magro & L. C. Raimondo Redazione di "Flora Mediterranea" Herbarium Mediterraneum Panormitanum, Università di Palermo Via Lincoln, 2 I-90133 Palermo, Italy [email protected] Printed by Luxograph s.r.l., Piazza Bartolomeo da Messina, 2/E - Palermo Registration at Tribunale di Palermo, no. 27 of 12 July 1991 ISSN: 1120-4052 printed, 2240-4538 online DOI: 10.7320/FlMedit26.001 Copyright © by International Foundation pro Herbario Mediterraneo, Palermo Contents V. Hugonnot & L. Chavoutier: A modern record of one of the rarest European mosses, Ptychomitrium incurvum (Ptychomitriaceae), in Eastern Pyrenees, France . 5 P. Chène, M. -

Natural Resources

Plants That Cause Problems – “Invasive Species” DestinationOakland.com STOP! What is an Invasive Species? Imagine spring wildflowers covered with a mat of twisted green vines. This is a sign that Oakland County Offenders invasive plants have moved in and native species have moved out. Invasive plant species originate in other parts of the world and are introduced into to the United States through flower a variety of ways. Not all plants introduced from other countries become invasive. The term invasive species is reserved for plants that grow and reproduce rapidly, causing changes to the areas where they become established. Invasive species impact our health, our economy seed and the environment, and can cost the United States $120 billion annually! flower pod flower A Ticking Time Bomb Growing unnoticed at first, invasive species spread and cover the landscape. They change the seed pod fruit ecology, affecting wildlife communities and the soil. Over time, invasive plant species form a monoculture in which the only plant growing is the invasive plant. Plants with Super Powers Invasive species have super powers to alter the ecological balance of nature. They flourish seed because controls in their native lands do not exist here. The Nature Conservancy ranks invasive species as the second leading cause of species extinction worldwide. Negative Effects of Invasive Species • Changes in hydrology— seed dispersal wetlands dry out • Release of chemicals into the soil that inhibit Black Swallow-wort Cynanchum louiseae & the growth of other plants. This is known as Pale Swallow-wort Cynanchum rossicum Autumn Olive Elaeagnus umbellate Garlic Mustard Allaria periolata Allelopathy. -

Rhamnus Crocea Nutt

I.SPECIES Rhamnus crocea Nutt. and Rhamnus ilicifolia Kellogg NRCS CODE: Family: Rhamnaceae 1. RHCR Order: Rhamnales 2. RHIL Subclass: Rosidae Class: Magnoliopsida Rhamnus crocea, San Bernardino Co., 5 June 2015, A. Montalvo Rhamnus ilicifolia, Riverside Co., Rhamnus ilicifolia, Riverside Co. Note the finely serrulate leaf 10 June 2015. A. Montalvo margins. 7 March 2008. A. Montalvo A. Subspecific taxa 1. None recognized by Sawyer (2012b) or in 2019 Jepson e-Flora whereas R. pilosa is recognized as R. c. 1. RHCR Nutt. subsp. pilosa (Trel.) C.B. Wolf in the PLANTS database (USDA PLANTS 2018). 2. RHIL 2. None B. Synonyms 1. RHCR 1 . Rhamnus croceus (spelling variant noted by FNA 2018) 2. RHIL 2. Rhamnus crocea Nutt. subsp. ilicifolia (Kellogg) C.B. Wolf; R. c. Nutt. var. ilicifolia (Kellogg) Greene (USDA PLANTS 2018) last modified: 3/4/2020 RHCR RHIL, page 1 printed: 3/10/2020 C. Common name The name red-berry, redberry, redberry buckthorn, California red-berry, evergreen buckthorn, spiny buckthorn, and hollyleaf buckthorn have been used for multiple taxa of Rhamnus (Painter 2016 a,b) 1. RHCR 1. Spiny redberry (Sawyer 2012a); also little-leaved redberry (Painter 2016a) 2. RHIL 2. Hollyleaf redberry (Sawyer 2012b); also holly-leaf buckthorn, holly-leaf coffeeberry (Painter 2016b) D. Taxonomic relationships There are about 150 species of Rhamnus worldwide and 14 in North America, 6 of which were introduced from other continents (Nesom & Sawyer 2018, FNA). This is after splitting the genus into Rhamnus (buckthorns and redberries) and Frangula (coffeeberries) based on a combination of fruit, leaf venation, and flower traits (Johnston 1975, FNA). -

The Habitat Preference of the Invasive Common Buckthorn in West Holland Sub-Watershed, Ontario

The Habitat Preference of The Invasive Common Buckthorn in West Holland Sub-watershed, Ontario by Ying Hong A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Forest Conservation Faculty of Forestry University of Toronto © Copyright by Ying Hong 2018 The Habitat Preference of The Invasive Common Buckthorn in West Holland Sub-watershed, Ontario Ying Hong Master of Forest Conservation Faculty of Forestry University of Toronto 2018 Abstract The project objective is to examine the habitat preference of the invasive common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica) in West Holland Sub-watershed located in the Lake Simcoe Watershed in Ontario. Filed data from monitoring plots, dispersed throughout the West Holland, were collected as part of the natural cover monitoring in the watershed during the summer of 2017. In my capstone project, I will 1) examine the possible plot characteristics that are related to common buckthorn presence; 2) explore whether and how common buckthorn abundance is related to the plot characteristics and disturbance; 3) determine the relationship between common buckthorn and other plants in the plot; and 4) give recommendations regard to current common buckthorn issue. This research can improve the knowledge of the invasive common buckthorn in Lake Simcoe Watershed, which is crucial because the non-native common buckthorn is distributed extensively across southern Ontario. ii Acknowledgments I want to say thank you to everyone who gives me physical or/and mental support! Thanks to my supervisor Dr. Danijela Puric-Mladenovic offer me summer job and give me lots of help and advice on the capstone project, and my crew leader Kyle Vanin from whom I learn a lot in the field; thanks, Katherine Baird help me with GIS; thanks to other VSP crews for collecting data together; and thanks to OMNR, especially my external supervisor Melanie Shapiera and Alex Kissel; thanks, Steve Varga, Richard Dickinson, Dave Bradley, Wasyl Bakowsky, Bodhan Kowalyk.