Prokofiev, Oistrakh, and the Flute Sonata Arranged for Violin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

95.3 Fm 95.3 Fm

October/NovemberMarch/April 2013 2017 VolumeVolume 41, 46, No. No. 3 1 !"#$%&'95.3 FM Brahms: String Sextet No. 2 in G, Op. 36; Marlboro Ensemble Saeverud: Symphony No. 9, Op. 45; Dreier, Royal Philharmonic WHRB Orchestra (Norwegian Composers) Mozart: Clarinet Quintet in A, K. 581; Klöcker, Leopold Quartet 95.3 FM Gombert: Missa Tempore paschali; Brown, Henry’s Eight Nielsen: Serenata in vano for Clarinet,Bassoon,Horn, Cello, and October-November, 2017 Double Bass; Brynildsen, Hannevold, Olsen, Guenther, Eide Pokorny: Concerto for Two Horns, Strings, and Two Flutes in F; Baumann, Kohler, Schröder, Concerto Amsterdam (Acanta) Barrios-Mangoré: Cueca, Aire de Zamba, Aconquija, Maxixa, Sunday, October 1 for Guitar; Williams (Columbia LP) 7:00 am BLUES HANGOVER Liszt: Grande Fantaisie symphonique on Themes from 11:00 am MEMORIAL CHURCH SERVICE Berlioz’s Lélio, for Piano and Orchestra, S. 120; Howard, Preacher: Professor Jonathan L. Walton, Plummer Professor Rickenbacher, Budapest Symphony Orchestra (Hyperion) of Christian Morals and Pusey Minister in The Memorial 6:00 pm MUSIC OF THE SOVIET UNION Church,. Music includes Kodály’s Missa brevis and Mozart’s The Eve of the Revolution. Ave verum corpus, K. 618. Scriabin: Sonata No. 7, Op. 64, “White Mass” and Sonata No. 9, 12:30 pm AS WE KNOW IT Op. 68, “Black Mass”; Hamelin (Hyperion) 1:00 pm CRIMSON SPORTSTALK Glazounov: Piano Concerto No. 2 in B, Op. 100; Ponti, Landau, 2:00 pm SUNDAY SERENADE Westphalian Orchestra of Recklinghausen (Turnabout LP) 6:00 pm HISTORIC PERFORMANCES Rachmaninoff: Vespers, Op. 37; Roudenko, Russian Chamber Prokofiev: Violin Concerto No. 2 in g, Op. -

Heinrich Neuhaus and Alternative Narratives of Selfhood in Soviet Russi

‘I wish for my life’s roses to have fewer thorns’: Heinrich Neuhaus and Alternative Narratives of Selfhood in Soviet Russia Abstract Heinrich Neuhaus (1888—1964) was the Soviet era’s most iconic musicians. Settling in Russia reluctantly he was dismayed by the policies of the Soviet State and unable to engage with contemporary narratives of selfhood in the wake of the Revolution. In creating a new aesthetic territory that defined himself as Russian rather than Soviet Neuhaus embodied an ambiguous territory whereby his views both resonated with and challenged aspects of Soviet- era culture. This article traces how Neuhaus adopted the idea of self-reflective or ‘autobiographical’ art through an interdisciplinary melding of ideas from Boris Pasternak, Alexander Blok and Mikhail Vrubel. In exposing the resulting tension between his understanding of Russian and Soviet selfhood, it nuances our understanding of the cultural identities within this era. Finally, discussing this tension in relation to Neuhaus’s contextualisation of the artistic persona of Dmitri Shostakovich, it contributes to a long- needed reappraisal of his relationship with the composer. I would like to gratefully acknowledge the support of the Guildhall School that enabled me to make a trip to archives in Moscow to undertake research for this article. Dr Maria Razumovskaya Guildhall School of Music & Drama, London Word count: 15,109 Key words: identity, selfhood, Russia, Heinrich Neuhaus, Soviet, poetry Contact email: [email protected] Short biographical statement: Maria Razumovskaya completed her doctoral thesis (Heinrich Neuhaus: Aesthetics and Philosophy of an Interpretation, 2015) as an AHRC doctoral scholar at the Royal College of Music in London. -

Sonata for Flute and Piano in D Major, Op. 94 by Sergey Prokofiev

SONATA FOR FLUTE AND PIANO IN D MAJOR, OP. 94 BY SERGEY PROKOFIEV: A PERFORMANCE GUIDE HONORS THESIS Presented to the Honors Committee of Texas State University-San Marcos in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation in the Honors ColLege by Danielle Emily Stevens San Marcos, Texas May 2014 1 SONATA FOR FLUTE AND PIANO IN D MAJOR, OP. 94 BY SERGEY PROKOFIEV: A PERFORMANCE GUIDE Thesis Supervisor: ________________________________ Kay Lipton, Ph.D. School of Music Second Reader: __________________________________ Adah Toland Jones, D. A. School of Music Second Reader: __________________________________ Cynthia GonzaLes, Ph.D. School of Music Approved: ____________________________________ Heather C. GaLLoway, Ph.D. Dean, Honors ColLege 2 Abstract This thesis contains a performance guide for Sergey Prokofiev’s Sonata for Flute and Piano in D Major, Op. 94 (1943). Prokofiev is among the most important Russian composers of the twentieth century. Recognized as a leading Neoclassicist, his bold innovations in harmony and his new palette of tone colors enliven the classical structures he embraced. This is especially evident in this flute sonata, which provides a microcosm of Prokofiev’s compositional style and highlights the beauty and virtuosic breadth of the flute in new ways. In Part 1 I have constructed an historical context for the sonata, with biographical information about Prokofiev, which includes anecdotes about his personality and behavior, and a discussion of the sonata’s commission and subsequent premiere. In Part 2 I offer an anaLysis of the piece with generaL performance suggestions and specific performance practice options for flutists that will assist them as they work toward an effective performance, one that is based on both the historically informed performance context, as well as remarks that focus on particular techniques, challenges and possible performance solutions. -

STATE SYMPHONIC KAPELLE of MOSCOW (Formerly the Soviet Philharmonic)

UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY in association with Manufacturers Bank STATE SYMPHONIC KAPELLE OF MOSCOW (formerly the Soviet Philharmonic) GENNADY ROZHDESTVENSKY Music Director and Conductor VICTORIA POSTNIKOVA, Pianist Saturday Evening, February 8, 1992, at 8:00 Hill Auditorium, Ann Arbor, Michigan The University Musical Society is grateful to Manufacturers Bank for a generous grant supporting this evening's concert. The box office in the outer lobby is open during intermission for tickets to upcoming concerts. Twenty-first Concert of the 113th Season 113th Annual Choral Union Series PROGRAM Russian Easter Festival Overture, Op. 36 ......... Rimsky-Korsakov Piano Concerto No. 3 in D minor, Op. 30 .......... Rachmaninoff Allegro ma non tanto Intermezzo: Adagio Finale: Alia breve Viktoria Postnikova, Pianist INTERMISSION Orchestral Suite No. 3 in G major, Op. 55 .......... Tchaikovsky Elegie Valse melancolique Scherzo Theme and Variations The pre-concert carillon recital was performed by Bram van Leer, U-M Professor of Aerospace Engineering. Viktoria Postnikova plays the Steinway piano available through Hammell Music, Inc. Livonia. The State Symphonic Kapelle is represented by Columbia Artists Management Inc., New York City. Russian Easter Festival Overture, Sheherazade, Op. 35. In his autobiography, My Musical Life, the composer said that these Op. 36 two works, along with the Capriccio espagnoie, NIKOLAI RIMSKY-KORSAKOV (1844-1908) Op. 34, written the previous year, "close a imsky-Korsakov came from a period of my work, at the end of which my family of distinguished military orchestration had attained a considerable and naval figures, so it is not degree of virtuosity and warm sonority with strange that in his youth he de out Wagnerian influence, limiting myself to cided on a career as a naval the normally constituted orchestra used by officer.R Both of his grandmothers, however, Glinka." These three works were, in fact, his were of humble origins, one being a peasant last important strictly orchestral composi and the other a priest's daughter. -

30N2 Programs

Sonata for Tuba and Piano Verne Reynolds FACULTY/PROFESSIONAL PERFORMANCES The Morning Song Roger Kellaway Edward R. Bahr, euphonium Salve Venere, Salve Marte John Stevens Concerto No. 1 for Hom, Op. 11 Richard Strauss Delta Sate University, Cleveland, MS 10/03/02 Csdrdds Vittorio Monti / arr. Ronald Davis Suite No. IV for Violoncello S. 1010 J.S. Bach Vocalises Giovanni Marco Bordogni Michael Fischer, tuba "Andante maestosoAndante mosso" Boise State University, Boise, ID WllljOl "Allegro" Central Missouri State University, Warrensburg, MO 11/1/02 (Johannes Rochut: Melodius Etudes No. 79, 24) Pittsburg State University, Pittsburg, KS 11/4/02 Concertino No. I in Bflat, op. 7 .Julius Klengel/an:. Leonard Falcone Romance Op. 36 Camille SaintSaens/arr. Michael Fischer GranA Concerto Friedebald Grafe Beelzebub Andrea V. Catozzi/arr. Julius S. Seredy Reverie et Balade Rene Mignion Three Romantic Pieces arr. Michael Fischer Danza Espagnola David Uber Du Ring an meinem Finger, Robert Schumann, Op. 42, No. 4 Velvet Brown, tuba Felteinsamkeit, Johannes Brahms Standchen, Franz Schubert *Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, OH 10/23/02 **Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 10/24/02 Gypsy Songs .Johannes Brahms/arr. by Michael Fischer Sonata Bruce Broughton The Liberation of Sisyphus John Stevens Chant du Menestrel, op. 71 Alexander Glazunov/arr. V. Brown Adam Frey, euphonium Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen Gustav Mahler/arr. D. Perantoni Mercer University, Macon, GAl0/01/02 *Te Dago Mi for tuba, euphonium and piano (U.S. premiere) Velvet Brown with Benjamin Pierce, euphonium Sormta in F Major.. Benedetto Marcello Blue Lake for Solo Euphonium **Mus!c for Two Big Instruments Alex Shapiro Fantasies David Gillingham Sonata for tuba and piano Juraj Filas Peace John Golland Rumanian Dance No. -

Teacher Notes on Russian Music and Composers Prokofiev Gave up His Popularity and Wrote Music to Please Stalin. He Wrote Music

Teacher Notes on Russian Music and Composers x Prokofiev gave up his popularity and wrote music to please Stalin. He wrote music to please the government. x Stravinsky is known as the great inventor of Russian music. x The 19th century was a time of great musical achievement in Russia. This was the time period in which “The Five” became known. They were: Rimsky-Korsakov (most influential, 1844-1908) Borodin Mussorgsky Cui Balakirev x Tchaikovsky (1840-’93) was not know as one of “The Five”. x Near the end of the Stalinist Period Prokofiev and Shostakovich produced music so peasants could listen to it as they worked. x During the 17th century, Russian music consisted of sacred vocal music or folk type songs. x Peter the Great liked military music (such as the drums). He liked trumpet music, church bells and simple Polish music. He did not like French or Italian music. Nor did Peter the Great like opera. Notes Compiled by Carol Mohrlock 90 Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (1882-1971) I gor Stravinsky was born on June 17, 1882, in Oranienbaum, near St. Petersburg, Russia, he died on April 6, 1971, in New York City H e was Russian-born composer particularly renowned for such ballet scores as The Firebird (performed 1910), Petrushka (1911), The Rite of Spring (1913), and Orpheus (1947). The Russian period S travinsky's father, Fyodor Ignatyevich Stravinsky, was a bass singer of great distinction, who had made a successful operatic career for himself, first at Kiev and later in St. Petersburg. Igor was the third of a family of four boys. -

Festival Artists

Festival Artists Cellist OLE AKAHOSHI (Norfolk competitions. Berman has authored two books published by the ’92) performs in North and South Yale University Press: Prokofiev’s Piano Sonatas: A Guide for the Listener America, Asia, and Europe in recitals, and the Performer (2008) and Notes from the Pianist’s Bench (2000; chamber concerts and as a soloist electronically enhanced edition 2017). These books were translated with orchestras such as the Orchestra into several languages. He is also the editor of the critical edition of of St. Luke’s, Symphonisches Orchester Prokofiev’s piano sonatas (Shanghai Music Publishing House, 2011). Berlin and Czech Radio Orchestra. | 27th Season at Norfolk | borisberman.com His performances have been featured on CNN, NPR, BBC, major German ROBERT BLOCKER is radio stations, Korean Broadcasting internationally regarded as a pianist, Station, and WQXR. He has made for his leadership as an advocate for numerous recordings for labels such the arts, and for his extraordinary as Naxos. Akahoshi has collaborated with the Tokyo, Michelangelo, contributions to music education. A and Keller string quartets, Syoko Aki, Sarah Chang, Elmar Oliveira, native of Charleston, South Carolina, Gil Shaham, Lawrence Dutton, Edgar Meyer, Leon Fleisher, he debuted at historic Dock Street Garrick Ohlsson, and André-Michel Schub among many others. Theater (now home to the Spoleto He has performed and taught at festivals in Banff, Norfolk, Aspen, Chamber Music Series). He studied and Korea, and has given master classes most recently at Central under the tutelage of the eminent Conservatory Beijing, Sichuan Conservatory, and Korean National American pianist, Richard Cass, University of Arts. -

Sergei Prokofiev

Sergei Prokofiev Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev (/prɵˈkɒfiɛv/; Russian: Сергей Сергеевич Прокофьев, tr. Sergej Sergeevič Prokof'ev; April 27, 1891 [O.S. 15 April];– March 5, 1953) was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor. As the creator of acknowledged masterpieces across numerous musical genres, he is regarded as one of the major composers of the 20th century. His works include such widely heard works as the March from The Love for Three Oranges, the suite Lieutenant Kijé, the ballet Romeo and Juliet – from which "Dance of the Knights" is taken – and Peter and the Wolf. Of the established forms and genres in which he worked, he created – excluding juvenilia – seven completed operas, seven symphonies, eight ballets, five piano concertos, two violin concertos, a cello concerto, and nine completed piano sonatas. A graduate of the St Petersburg Conservatory, Prokofiev initially made his name as an iconoclastic composer-pianist, achieving notoriety with a series of ferociously dissonant and virtuosic works for his instrument, including his first two piano concertos. In 1915 Prokofiev made a decisive break from the standard composer-pianist category with his orchestral Scythian Suite, compiled from music originally composed for a ballet commissioned by Sergei Diaghilev of the Ballets Russes. Diaghilev commissioned three further ballets from Prokofiev – Chout, Le pas d'acier and The Prodigal Son – which at the time of their original production all caused a sensation among both critics and colleagues. Prokofiev's greatest interest, however, was opera, and he composed several works in that genre, including The Gambler and The Fiery Angel. Prokofiev's one operatic success during his lifetime was The Love for Three Oranges, composed for the Chicago Opera and subsequently performed over the following decade in Europe and Russia. -

Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847, Germany) Prepared by David Barker

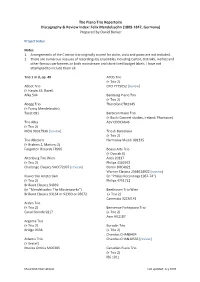

The Piano Trio Repertoire Discography & Review Index: Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847, Germany) Prepared by David Barker Project Index Notes 1. Arrangements of the C minor trio originally scored for violin, viola and piano are not included. 2. There are numerous reissues of recordings by ensembles including Cortot, Oistrakh, Heifetz and other famous performers on both mainstream and short-lived budget labels. I have not attempted to include them all. Trio 1 in d, op. 49 ATOS Trio (+ Trio 2) Abbot Trio CPO 7775052 [review] (+ Haydn 43, Ravel) Afka 544 Bamberg Piano Trio (+ Trio 2) Abegg Trio Thorofon CTH2345 (+ Fanny Mendelssohn) Tacet 091 Barbican Piano Trio (+ Bush: Concert studies, Ireland: Phantasie) Trio Alba ASV CDDCA646 (+ Trio 2) MDG 90317936 [review] Trio di Barcelona (+ Trio 2) Trio Albeneri Harmonia Mundi 901335 (+ Brahms 2, Martinu 2) Forgotten Records FR995 Beaux Arts Trio (+ Dvorak 4) Altenburg Trio Wien Ades 20337 (+ Trio 2) Philips 4162972 Challenge Classics SACC72097 [review] Doron DRC4021 Warner Classics 2564614922 [review] Klaviertrio Amsterdam (in “Philips Recordings 1967-74”) (+ Trio 2) Philips 4751712 Brilliant Classics 94039 (in “Mendelssohn: The Masterworks”) Beethoven Trio Wien Brilliant Classics 93164 or 92393 or 93672 (+ Trio 2) Camerata 32CM141 Arden Trio (+ Trio 2) Benvenue Fortepiano Trio Canal Grande 9217 (+ Trio 2) Avie AV2187 Argenta Trio (+ Trio 2) Borodin Trio Bridge 9338 (+ Trio 2) Chandos CHAN8404 Atlantis Trio Chandos CHAN10535 [review] (+ Sextet) Musica Omnia MO0205 Canadian Piano Trio (+ Trio 2) IBS 1011 MusicWeb International Last updated: July 2020 Piano Trios: Mendelssohn Profil PH08027 Trio Carlo Van Neste (+ Trio 2) Florestan Trio Pavane ADW7572 (+ Trio 2) Hyperion CDA67485 [review] Ceresio Trio (+ Trio 2, Viola trio) Trio Fontenay Doron 3060 (+ Trio 2) Teldec 44947 Chung Trio (in “Mendelssohn Edition Vol. -

The Flute Works of Erwin Schulhoff

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Dissertations Student Research 8-2019 The Flute Works of Erwin Schulhoff Sara Marie Schuhardt Follow this and additional works at: https://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Schuhardt, Sara Marie, "The Flute Works of Erwin Schulhoff" (2019). Dissertations. 590. https://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations/590 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © 2019 SARA MARIE SCHUHARDT ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School THE FLUTE WORKS OF ERWIN SCHULHOFF A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Arts Sara Marie Schuhardt College of Performing and Visual Arts School of Music August 2019 This Dissertation by: Sara Marie Schuhardt Entitled: The Flute Works of Erwin Schulhoff has been approved as meeting the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Arts in College of Performing and Visual Arts in School of Music Accepted by the Doctoral Committee ______________________________________________________ Carissa Reddick, Ph.D., Research Advisor ______________________________________________________ James Hall, D.M.A., Committee Member _______________________________________________________ -

Frédéric Chopin, Sviatoslav Richter, Martha Argerich, Mstislav

Frédéric Chopin Sonate Op.65, Polonaise Brillante, Ballades no. 3 & no. 4 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Sonate Op.65, Polonaise Brillante, Ballades no. 3 & no. 4 Country: Germany Style: Romantic MP3 version RAR size: 1401 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1220 mb WMA version RAR size: 1211 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 864 Other Formats: MMF TTA MP4 AC3 AU AAC DTS Tracklist Hide Credits Sonata For Piano And Violoncello In G Minor, Op. 65 Piano – Martha ArgerichVioloncello – Mstislav Rostropovich 1 Allegro Moderato 15:15 2 Scherzo. Allegro Con Brio 4:50 3 Largo 3:41 4 Finale. Allegro 5:27 5 Polonaise Brillante In C Major, Op.3 8:09 Ballade No. 3 In A Flat Major, Op. 47 6 7:15 Piano – Sviatoslav Richter 7 Ballade No. 4 In F Minor, Op. 52 11:25 Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 028943158329 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Frédéric Chopin / Martha Argerich, Mstislav Frédéric Chopin / Rostropovich, Svjatoslav Martha Argerich, Richter* - Cellosonate Deutsche 431 583-2 Mstislav 431 583-2 US 1991 Op.65 • Polonaise Grammophon Rostropovich, Brillante • Balladen Svjatoslav Richter* Op.47 & Op.52 (CD, Album) Related Music albums to Sonate Op.65, Polonaise Brillante, Ballades no. 3 & no. 4 by Frédéric Chopin Moscow Radio Orchestra With Mstislav Rostropovich And Sviatoslav Richter - Saint-Saens Cello Concerto Op.33, Prokofiev Cello Sonata Op.119 Various - The Originals - Highlights Argerich • Rostropovitch - Schumann • Chopin - National Symphony Orchestra Of Washington - Klavierkonzert Beethoven - Mstislav Rostropovich ‧ Sviatoslav Richter - The Complete Sonatas For Piano And Cello L.v. -

Monday, July 1, 2013 8:00 Pm Bohuslav Martinů Sergei Prokofiev

MONDAY, JULY 1, 2013 8:00 PM PROGRAM BOHUSLAV MARtinů La Revue de cuisine Prologue (Allegretto) Introduction (Tempo di marcia) Danse du moulinet autour du chaudron (Poco meno) Danse du chaudron et du couvercle (Allegro) Tango (Danse d’amour. Lento) Duel (Poco a poco allegro. Tempo di Charleston) Entr’acte (Lamentation du chaudron. Allegro moderato) Marche funèbre (Adagio) Danse radieuse (Tempo di marcia) Fin du drame (Allegretto) Sean Osborn clarinet / Seth Krimsky bassoon / Jens Lindemann trumpet / James Ehnes violin / David Requiro cello / Inon Barnatan piano SERGEI PROKOFIEV Sonata for Violin and Piano in D Major, Op. 94bis Moderato Scherzo: Presto Andante Allegro con brio Jesse Mills violin / Andrew Armstrong piano INTERMISSION PIOTR TCHAIKOVSKY String Quartet No. 3 in E-flat minor, Op. 30 Andante sostenuto—Allegro moderato Allegretto vivo e scherzando Andante funebre e doloroso, ma con moto Finale: Allegro non troppo e risoluto Ida Levin violin / Stephen Rose violin / Rebecca Albers viola / Brinton Smith cello SEASON SPONSORSHIP PROVIDED BY TOBY saks AND DR. MARTIN GREENE BOHUSLAV MARtinů throughout the scintillating score, especially noticeable (1890–1959) in frequent use of muted trumpet and pizzicato cello La Revue de cuisine (1927) lines that assume a jazz ensemble’s deployment of a double bass. Largely self-taught in composition, Bohuslav Martinů drew inspiration and influence from a number of 20th- A bright trumpet fanfare launches the animated century stylistic languages, including Bohemian and Prologue, soon yielding to a stomping piano solo that Moravian folk music, Stravinskian neo-Classicism, the itself launches the Introduction proper, a contrapuntal music of Albert Roussel and Debussy, as well as early dance engaging the remaining instruments.