Possible World the Possible World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ed Carpenter, Artist [email protected] Commissions

ED CARPENT ER 1 Ed Carpenter, Artist [email protected] Revision 2/1/21 Born: Los Angeles, California. 1946 Education: University of California, Santa Barbara 1965-6, Berkeley 1968-71 Ed Carpenter is an artist specializing in large-scale public installations ranging from architectural sculpture to infrastructure design. Since 1973 he has completed scores of projects for public, corporate, and ecclesiastical clients. Working internationally from his studio in Portland, Oregon, USA, Carpenter collaborates with a variety of expert consultants, sub-contractors, and studio assistants. He personally oversees every step of each commission, and installs them himself with a crew of long-time helpers, except in the case of the largest objects, such as bridges. While an interest in light has been fundamental to virtually all of Carpenter’s work, he also embraces commissions that require new approaches and skills. This openness has led to increasing variety in his commissions and a wide range of sites and materials. Recent projects include interior and exterior sculptures, bridges, towers, and gateways. His use of glass in new configurations, programmed artificial lighting, and unusual tension structures have broken new ground in architectural art. He is known as an eager and open-minded collaborator as well as technical innovator. Carpenter is grandson of a painter/sculptor, and step-son of an architect, in whose office he worked summers as a teenager. He studied architectural glass art under artists in England and Germany during the early 1970’s. Information on his projects and a video about his methods can be found at: http://www.edcarpenter.net/ Commissions Bridge And Exterior Public Commissions 2019: Barbara Walker Pedestrian Bridge, Wildwood Trail, Portland, OR, 180’ x 12’ x 8’. -

Rewriting Universes: Post-Brexit Futures in Dave Hutchinson’S Fractured Europe Quartet

humanities Article Rewriting Universes: Post-Brexit Futures in Dave Hutchinson’s Fractured Europe Quartet Hadas Elber-Aviram Department of English, The University of Notre Dame (USA) in England, London SW1Y 4HG, UK; [email protected] Abstract: Recent years have witnessed the emergence of a new strand of British fiction that grapples with the causes and consequences of the United Kingdom’s vote to leave the European Union. Building on Kristian Shaw’s pioneering work in this new literary field, this article shifts the focus from literary fiction to science fiction. It analyzes Dave Hutchinson’s Fractured Europe quartet— comprised of Europe in Autumn (pub. 2014), Europe at Midnight (pub. 2015), Europe in Winter (pub. 2016) and Europe at Dawn (pub. 2018)—as a case study in British science fiction’s response to the recent nationalistic turn in the UK. This article draws on a bespoke interview with Hutchinson and frames its discussion within a range of theories and studies, especially the European hermeneutics of Hans-Georg Gadamer. It argues that the Fractured Europe quartet deploys science fiction topoi to interrogate and criticize the recent rise of English nationalism. It further contends that the Fractured Europe books respond to this nationalistic turn by setting forth an estranged vision of Europe and offering alternative modalities of European identity through the mediation of photography and the redemptive possibilities of cooking. Keywords: speculative fiction; science fiction; utopia; post-utopia; dystopia; Brexit; England; Europe; Dave Hutchinson; Fractured Europe quartet Citation: Elber-Aviram, Hadas. 2021. Rewriting Universes: Post-Brexit 1. Introduction Futures in Dave Hutchinson’s Fractured Europe Quartet. -

Lorella Belli Literary Agency Ltd Lbf 2019

LORELLA BELLI LITERARY AGENCY LTD Translation Rights List LBF 2019 lbla lorella belli literary agency ltd 54 Hartford House 35 Tavistock Crescent Notting Hill London W11 1AY, UK Tel. 0044 20 7727 8547 [email protected] Lorella Belli Literary Agency Ltd. Registered in England and Wales. Company No. 11143767. Registered Office: 54 Hartford House, 35 Tavistock Crescent, Notting Hill, London W11 1AY, United Kingdom. 1 Fiction: New Titles/Authors Nisha Minhas Selected Backlist includes: Rick Mofina Taylor Adams Kirsty Moseley Renita D’Silva Ingrid Alexandra Owen Mullen Helen Durrant J A Baker Steve Parker Joy Ellis TJ Brearton Katie Stephens Charlie Gallagher Ruth Dugdall Mark Tilbury Sibel Hodge Ker Dukey Victoria Van Tiem Ana Johns Hannah Fielding Anita Waller Carol Mason Janice Frost Alex Walters Nicola May Sophie Jackson PP Wong Dreda Say Mitchell Maggie James Dylan H Jones Betsy Reavley Sharon Maas Alison J Waines Selected Bookouture authors (no new submissions, but handling existing deals/publishers only): Mandy Baggot Anna Mansell Rebecca Stonehill Robert Bryndza Angela Marsons Fiona Valpy Colleen, Coleman Helen Phifer Sue Watson Jenny Hale Helen Pollard Carol Wyer Arlene Hunt Kelly Rimmer Louise Jensen Claire Seeber Non-Fiction: New Titles Sally Corner Gerald Posner Marcus Ferrar Patricia Posner Hira Ali Tamsen Garrie Robert J Ray Nick Baldock/Bob Hayward Girl on the Net Tam Rodwell Christopher Lascelles Jonathan Sacks Selected Backlist Jeremy Leggett Grace Saunders -

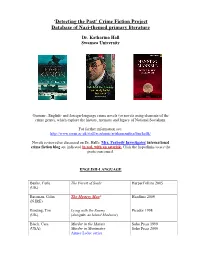

'Detecting the Past' Crime Writing Project

‘Detecting the Past’ Crime Fiction Project Database of Nazi-themed primary literature Dr. Katharina Hall Swansea University German-, English- and foreign-language crime novels (or novels using elements of the crime genre), which explore the history, memory and legacy of National Socialism. For further information see: http://www.swan.ac.uk/staff/academic/artshumanities/ltm/hallk/ Novels reviewed or discussed on Dr. Hall's 'Mrs. Peabody Investigates' international crime fiction blog are indicated in red, with an asterisk. Click the hyperlinks to see the posts concerned. ENGLISH-LANGUAGE Banks, Carla The Forest of Souls HarperCollins 2005 (UK) Bateman, Colin The Mystery Man* Headline 2009 (N.IRE) Binding, Tim Lying with the Enemy Picador 1998 (UK) (also pub. as Island Madness) Black, Cara Murder in the Marais Soho Press 1999 (USA) Murder in Montmatre Soho Press 2006 Aimee Leduc series Broderick, William The Sixth Lamentation* (see Time Warner 2004 [2003] (UK) discussion in comments section) Father Anselm series Brophy, Grace A Deadly Paradise Soho Press 2008 (US) Le Carré, John Call for the Dead* Penguin 2012 [1961] (UK) Penguin 2010 [1963] The Spy who Came in from the Cold* George Smiley #1 and #3 Sceptre 1999 [1968] A Small Town in Germany* Chabon, Michael The Final Solution Harper Perennial 2008 (USA) [2005] The Yiddish Policemen’s Union* Harper Perennial 2008 [2007] Cook, Thomas H. Instruments of Night Bantam 1999 (USA) Crispin, Edmund Holy Disorders Vintage 2007 [1946] (UK) Crombie, Deborah Where Memories Lie Macmillan 2009 [2008] -

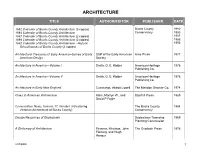

Architecture

ARCHITECTURE TITLE AUTHOR/EDITOR PUBLISHER DATE 1982 Calendar of Bucks County Architecture (3 copies) Bucks County 1982 1983 Calendar of Bucks County Architecture Conservancy 1983 1987 Calendar of Bucks County Architecture (2 copies) 1987 1988 Calendar of Bucks County Architecture (2 copies) 1988 1992 Calendar of Bucks County Architecture --Historic 1992 Schoolhouses of Bucks County (2 copies) Architectural Treasures of Early America--Survey of Early Staff of the Early American Arno Press 1977 American Design Society Architecture in America—Volume I Smith, G. E. Kidder American Heritage 1976 Publishing Co. Architecture in America—Volume II Smith, G. E. Kidder American Heritage 1976 Publishing Co. Architecture in Early New England Cummings, Abbott Lowell The Meridon Gravure Co. 1974 Clues to American Architecture Klein, Marilyn W., and Starrhill Press 1985 David P Fogle Conservation News, Volume 17, Number 3 (Featuring The Bucks County 1984 Victorian Architecture of Bucks County) Conservancy Design Resources of Doylestown Doylestown Township 1969 Planning Commission A Dictionary of Architecture Pevsner, Nikolaus, John The Overlook Press 1976 Fleming, and Hugh Honour 4/27/2009 1 ARCHITECTURE TITLE AUTHOR/EDITOR PUBLISHER DATE Early Domestic Architecture of Connecticut Kelly, J. Frederick Dover Publications. 1952 Early Domestic Architecture of Pennsylvania (2 copies) Raymond, Eleanor Schiffer Publishing 1977 A Field Guide to American Architecture Rifkind, Carole New American Library 1980 Pennsylvania Architecture—The Historic American Burns, Deborah Stephens, Commonwealth of 2000 Buildings Survey 1933-1990 and Richard J. Webster Pennsylvania; Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission Pennsylvania School of Architecture Burrowes, Thomas H. Commonwealth of 1856 Pennsylvania Tidewater Maryland Architecture and Gardens Forman, Henry Chandlee Bonanza Books 1956 Victorian Architecture Bicknell, A. -

The Extraordinary Flight of Book Publishing's Wingless Bird

LOGOS 12(2) 3rd/JH 1/11/06 9:46 am Page 70 LOGOS The extraordinary flight of book publishing’s wingless bird Eric de Bellaigue “Very few great enterprises like this survive their founder.” The speaker was Allen Lane, the founder of Penguin, the year before his death in 1970. Today the company that Lane named after the wingless bird has soared into the stratosphere of the publishing world. How this was achieved, against many obstacles and in the face of many setbacks, invites investigation. Eric de Bellaigue has been When Penguin Books was floated on the studying the past and forecasting Stock Exchange in April 1961, it already had the future of British book twenty-five profitable years behind it. The first ten Penguin reprints, spearheaded by André Maurois’ publishing for thirty-five years. Ariel and Ernest Hemingway’s Farewell to Arms, In this first instalment of a study came out in 1935 under the imprint of The Bodley of Penguin Books, he has Head, but with Allen Lane and his two brothers combined his financial insights underwriting the venture. In 1936, Penguin Books Limited was incorporated, The Bodley Head having with knowledge gleaned through been placed into voluntary receivership. interviews with many who played The story goes that the choice of the parts in Penguin’s history. cover price was determined by Woolworth’s slogan Subsequent instalments will bring “Nothing over sixpence”. Woolworths did indeed de Bellaigue’s account up to the stock the first ten titles, but Allen Lane attributed his selection of sixpence as equivalent to a packet present day. -

Asian Art Books.Xlsx

The FloatingWorld The Story of Japanese Prints By James A. Michener 1954 Random House LOC 54-7812 1st Printng Chinoiserie Dawn Jacobson Phaidon Press Ltd London ISBN 0-714828831 1993 Dust Jacket Chinese Calligraphy Tseng Yu-ho Ecke Philadelphia Museum of Art 1971 1971 LOC 75-161453 Second Printing Soft Cover Treasures of Asia Chinese Painting Text by James Cahill James Cahill The World Publishing Co. Cleveland Copyright by Editions d'Art Albert Skira, 1960 LOC 60- 15594 Painting in the Far East Laurence Binyon 3rd Edition Revised Throughout Dova Publication, NY Soft Cover The Year One Art of the Ancient World East and West The Metropolitan Museum of Art Edited by Elizabeth J. Milleker Yale University Press 2000 Dust Jacket A Shoal of Fishes Hiroshige The Metropolitan Museum of Art The Viking Press Studio Book 1980 LOC 80-5170 ISBN 0-87099-237-6 Sleeve Past, Present, East and West Sherman E. Lee George Braziller, Inc. New York 1st Printing ISBN 0-8076-1064-x Dust Jacket Birds, Beast, Blossoms, and Bugs The Nature of Japan Text by Harold P. Stern Harry N. Abrams, Inc. LOC 75-46630 Cultural Relics Unearted in China 1973 Wenwu Press Peking, 1972 w/ intro in English- Translation of the Intro and the Contents of: Cultural Relics Unearthed During the Period of the Great Cultural Revolution prepared by China Books & Periodicals Dust Jacket & Sleeve Chinese Art and Culture Rene Grousset Translated from the Frenchby Haakon Chevalier E-283 1959 Orion Press, Inc. Paper Second Printing Chinese Bronzes 70 Plates in Full Colour Mario Bussagli Translated by Pamela Swinglehurst from the Italian original Bronzi Cinesi 1969 The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited Dust Jacket Chinese Art from the Cloud Wampler and other Collections in the Everson Museum Intro by Max Loehr Handbook of the collection by Celia Carrington Riely Frederick A . -

2010 Financial Statements for Bertelsmann AG

TRANSLATION Financial Statements as of December 31, 2010 and Management Report Bertelsmann AG, Gütersloh Contents Balance sheet Income statement Notes Annex to the notes List of shareholders, as required by § 285 no. 11 HGB Management report Auditor's report Responsibility statement 2 Balance Sheet of Bertelsmann AG as of December 31, 2010 ASSETS 31/12/2010 31/12/2009 Notes € €€ millions Non-current assets Intangible assets (1) 1,059,322.00 1 Property, plant and equipment (2) 190,190,821.32 214 Financial assets (3) 10,994,781,933.78 11,065 11,186,032,077.10 11,280 Current assets Receivables and other assets (4) 1,322,008,799.76 1,652 Securities (5) 25,011,784.00 79 Cash and cash equivalents (6) 759,763,413.60 1,267 2,106,783,997.36 2,998 Prepaid expenses (7) 9,063,668.91 10 13,301,879,743.37 14,288 SHAREHOLDERS' EQUITY AND LIABILITIES 31/12/2010 31/12/2009 Notes € €€ millions Eigenkapital Subscribed capital (8) 1,000,000,000.00 1,000 Profit participation capital (9) 412,596,446.28 706 Capital reserve 2,600,000,000.00 2,600 Retained earnings (10) 1,879,397,473.52 1,873 Unappropriated income 1,321,836,000.00 1,314 7,213,829,919.80 7,493 Untaxed reserves (11) 0.00 4 Provisions Provisions for pensions and similar obligations (12) 226,882,654.00 187 Other provisions (13) 93,733,994.06 83 320,616,648.06 270 Financial debt (14) 3,246,621,396.82 3,380 Other liabilities (15) 2,516,093,653.85 3,134 Deferred income (16) 4,718,124.84 7 13,301,879,743.37 14,288 3 INCOME STATEMENT for the period from January 1 to December 31, 2010 2010 2009 Notes €€ -

Nancy+ Azara+ CV

A.I.R. NANCY AZARA CV website: nancyazara.com email: [email protected] EDUCATION AAS Finch College, N.Y. BS Empire State College S.U.N.Y Art Students League of New York, Sculpture with John Hovannes, Painting and Drawing with Edwin Dickinson Lester Polakov Studio of Stage Design, New York City SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2021 High Chair and Other Works, A.I.R. Gallery, Brooklyn, NY 2020 Gold Coat with Red Triangle, Gallery Z, Windows Exhibition, New York, NY 2019 The Meeting of the Birds, curated by Robert Tomlinson, Kaaterskill Fine Arts Gallery, Hunter Village Square, NY 2018 Nancy Azara: Nature Prints, a cabinet installation, curated by Claudia Sbrissa, Saint John’s University, Queens, NY 2017 Passage of the Ghost Ship: Trees and Vines, The Picture Gallery at The Saint- Gaudens Memorial, Cornish, New Hampshire 2016 Tuscan Spring: Rubbings, Scrolls and Other Works, curated by Harry J Weil, A.I.R. Gallery, Brooklyn, NY 2015 Allegory of Leaves, (3 person show) The Harold B. Lemmerman Gallery, New Jersey City University, Jersey City, NJ 2015 I am the Vine, You are the Branches, St. Ann & the Holy Trinity Church, Brooklyn, NY 2013 Of leaves and vines . A shiing braid of lines, SACI Gallery, Florence, Italy 2012 Natural Linking, (3 Person Show) Traffic Zone Center for Visual Arts, Minneapolis, MN 2011 Spirit Taking Form: Rubbings, Tracings and Carvings, Gaga Arts Center, Garnerville, NY 2010 Spirit Taking Form: Rubbings, Tracings and Carvings, Fairleigh Dickinson University, Teaneck, NJ 2010 Nancy Azara: Winter Song, Andre Zarre Gallery, NYC, NY 2009 Nancy Azara, Suffolk Community College, Long Island, NY 2008 Nancy Azara, Sanyi Museum, Miaoli, Taiwan 2008 Maxi’s Wall, A.I.R. -

Download 296796.Pdf

Case 1:12-cv-02826-DLC Document 233-1 Filed 05/14/13 Page 1 of 103 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK __________________________________________ UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Civil Action No. 12-CV-2826 (DLC) ) APPLE, INC., et al., ) ) Defendants. ) __________________________________________) __________________________________________ ) THE STATE OF TEXAS; ) THE STATE OF CONNECTICUT; et al., ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) Civil Action No. 12-cv-03394 (DLC) ) PENGUIN GROUP (USA) INC. et al., ) ) Defendants. ) __________________________________________) PLAINTIFFS’ PROPOSED FINDINGS OF FACT Case 1:12-cv-02826-DLC Document 233-1 Filed 05/14/13 Page 2 of 103 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 1 II. DEFENDANTS .................................................................................................................. 4 A. Litigating Defendants ........................................................................................... 4 B. Settled Defendants ............................................................................................... 4 III. BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................ 5 A. The Publishing Industry ....................................................................................... 5 B. Amazon Ushered in the Modern E-Book Era in 2007 with the Kindle Device and Low E-Book -

2020 Financial Statements for Bertelsmann SE & Co. Kgaa

Financial Statements and Combined Management Report Bertelsmann SE & Co. KGaA, Gütersloh December 31, 2020 Contents Balance sheet Income statement Notes to the financial statements Combined Management Report Responsibility Statement Auditor’s report 1 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Assets as of December 31, 2020 in € millions Notes 12/31/2020 12/31/2019 Non-current assets Intangible assets Acquired industrial property rights and similar rights as well as licenses to such rights 1 9 8 9 8 Tangible assets Land, rights equivalent to land and buildings 1 306 311 Technical equipment and machinery 1 1 1 Other equipment, fixtures, furniture and office equipment 1 42 47 Advance payments and construction in progress 1 7 2 356 361 Financial assets Investments in affiliated companies 1 15,974 14,960 Loans to affiliated companies 1 230 712 Investments 1 - - Non-current securities 1 1,461 1,252 17,665 16,924 18,030 17,293 Current assets Receivables and other assets Accounts receivable from affiliated companies 2 4,893 4,392 Other assets 2 94 148 4,987 4,540 Securities Other securities - - Cash on hand and bank balances 3 2,476 513 7,463 5,053 Prepaid expenses and deferred charges 4 20 20 25,513 22,366 2 Equity and liabilities as of December 31, 2020 in € millions Notes 12/31/2020 12/31/2019 Equity Subscribed capital 5 1,000 1,000 Capital reserve 2,600 2,600 Retained earnings Legal reserve 100 100 Other retained earnings 6 5,685 5,485 5,785 5,585 Net retained profits 898 663 10,283 9,848 Provisions Provisions for pensions and similar obligations 7 377 357 Provision -

2013 Financial Statements for Bertelsmann SE & Co. Kgaa

ANNUAL FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AS OF DECEMBER 31, 2013, AND MANAGEMENT REPORT BERTELSMANN SE & CO. KGaA, GÜTERSLOH (Translation – the German text is authorative) Annual financial statements 2013 Contents Balance sheet Income statement Notes “List of shareholdings” annex to the notes in accordance with HGB 285 (11) Management report Auditor’s report Responsibility statement 2 Annual financial statements 2013 Bertelsmann SE & Co. KGaA Balance sheet as of December 31, 2013 Assets 12/31/2013 Previous year Notes € € € millions Non-current assets Intangible assets (1) 844,280.30 1 Tangible assets (2) 291,216,329.92 237 Financial assets (3) 12,747,359,728.83 11,404 13,039,420,339.05 11,642 Current assets Receivables and other assets (4) 1,736,575,805.91 913 Securities 1.00 - Cash and cash equivalents (5) 1,425,121,750.94 1,612 3,161,697,557.85 2,525 Prepaid expenses and deferred charges (6) 12,218,335.49 15 16,213,336,232.39 14,182 Shareholders’ equity and liabilities 12/31/2013 Previous year Notes € € € millions Shareholders’ equity Subscribed capital (7) 1,000,000,000.00 1,000 Capital reserve 2,600,000,000.00 2,600 Retained earnings (8) 3,662,000,000.00 2,462 Unappropriated income 1,189,896,716.49 862 8,451,896,716.49 6,924 Provisions Pensions and similar obligations (9) 244,299,057.00 235 Other provisions (10) 117,124,440.50 99 361,423,497.50 334 Financial debt (11) 3,506,024,666.89 3,790 Other liabilities (12) 3,893,702,490.50 3,132 Deferred income (13) 288,861,01 2 16,213,336,232.39 14,182 3 Annual financial statements 2013 Bertelsmann SE & Co.