Robert S. Bennett, Esquire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Class of 2003 Finals Program

School of Law One Hundred and Seventy-Fourth FINAL EXERCISES The Lawn May 18, 2003 1 Distinction 2 High Distinction 3 Highest Distinction 4 Honors 5 High Honors 6 Highest Honors 7 Distinguished Majors Program School of Law Finals Speaker Mortimer M. Caplin Former Commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service Mortimer Caplin was born in New York in 1916. He came to Charlottesville in 1933, graduating from the College in 1937 and the Law School in 1940. During the Normandy invasion, he served as U.S. Navy beachmaster and was cited as a member of the initial landing force on Omaha Beach. He continued his federal service as Commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service under President Kennedy from 1961 to 1964. When he entered U.Va. at age 17, Mr. Caplin committed himself to all aspects of University life. From 1933-37, he was a star athlete in the University’s leading sport—boxing—achieving an undefeated record for three years in the mid-1930s and winning the NCAA middleweight title in spite of suffering a broken hand. He also served as coach of the boxing team and was president of the University Players drama group. At the School of Law, he was editor-in-chief of the Virginia Law Review and graduated as the top student in his class. In addition to his deep commitment to public service, he is well known for his devotion to teaching and to the educational process and to advancing tax law. Mr. Caplin taught tax law at U.Va. from 1950-61, while serving as president of the Atlantic Coast Conference. -

Kendrick CV 2021-4.2

LESLIE CAROLYN KENDRICK University of Virginia School of Law Charlottesville, VA 22903 [email protected] EMPLOYMENT UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA SCHOOL OF LAW, Charlottesville, Virginia Vice Dean, July 2017-present White Burkett Miller Professor of Law and Public Affairs, August 2020-present David H. Ibbeken ’71 Research Professor of Law Professor of Law, August 2018-present Albert Clark Tate, Jr., Research Professor of Law, August 2014-August 2017 Professor of Law, 2013-2020 Associate Professor of Law, 2008-2013 HARVARD LAW SCHOOL, Cambridge, Massachusetts VisitinG Professor of Law, January 2017 UCLA SCHOOL OF LAW, Los Angeles, California VisitinG Professor of Law, January 2013-May 2013 THE HONORABLE DAVID H. SOUTER, Supreme Court of the United States Law Clerk, July 2007-July 2008 THE HONORABLE J. HARVIE WILKINSON, III, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit Law Clerk, June 2006-June 2007 EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA SCHOOL OF LAW, Charlottesville, Virginia J.D., May 2006 Hardy Cross Dillard Scholarship (full merit scholarship) UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD, Magdalen College, Oxford, UK D.Phil., English Literature, November 2003 M.Phil. with Distinction, English Literature, June 2000 Rhodes Scholarship (Kentucky & Magdalen 1998) UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHAPEL HILL, Chapel Hill, North Carolina B.A. with Highest Distinction, Classics and English, May 1998 Morehead Scholarship (full merit scholarship) Kendrick, 2 of 7 HONORS AND AWARDS Elected to American Law Institute (2017) University of Virginia All-University Teaching Award (2017) Carl McFarland Prize (for outstanding research by a junior member of UVA law faculty, 2014) Margaret G. Hyde Award (highest award given to member of graduating class at UVA Law, 2006) Virginia State Bar Family Law Book Award (2006) Judge John R. -

Philip C. Jessup Papers a Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress

Philip C. Jessup Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2003 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Catalog Record: https://lccn.loc.gov/mm78027771 Additional search options available at: https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms004004 Prepared by Allen H. Kitchens and Audrey Walker Revised and expanded by Connie L. Cartledge with the assistance of Michael W. Giese and Susie H. Moody Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Manuscript Division, 2004 Revised 2010 April Collection Summary Title: Philip C. Jessup Papers Span Dates: 1574-1983 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1925-1983) ID No.: MSS27771 Creator: Jessup, Philip C. (Philip Caryl), 1897-1986 Extent: 120,000 items Extent: 394 containers plus 2 oversize and 1 classified Extent: 157.6 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. LC Catalog record: https://lccn.loc.gov/mm78027771 Summary: Jurist, diplomat, and educator. Family and general correspondence, reports and memoranda, speeches and writings, subject files, legal papers, newspaper clippings and other papers pertaining chiefly to Jessup's work with the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Institute of Pacific Relations, United States Department of State, United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration, and International Court of Justice. Includes material relating to his World War I service in Spartanburg, S.C., and in France; and to charges made against him by Senator Joseph McCarthy and postwar loyalty and security investigations. Also includes papers of his wife, Lois Walcott Kellogg Jessup, relating to her work for the American Friends Service Committee, United States Children's Bureau, and United Nations, her travels to Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East, and to her writings. -

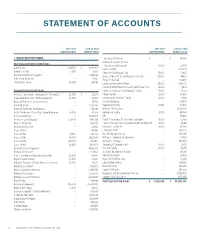

Statement of Accounts

STATEMENT OF ACCOUNTS 2019–2020 June 30, 2020 2019–2020 June 30, 2020 CONTRIBUTIONS MARKET VALUE CONTRIBUTIONS MARKET VALUE I. UNRESTRICTED FUNDS Lawrence W. I’Anson $ – $ 88,958 Michael R. Lincoln ’91 and Non–Endowed Unrestricted Funds Wendy Lavalle Lincoln 10,000 20,725 Current Use $ 4,249,758 $ 3,914,923 Henry C. Little – 1,104,129 Ernest L. Folk III 1,000 4,750 Deborah Platt Majoras ’89 15,000 31,835 General Academic Programs – 2,817,534 Marco V. Masotti ’92 and Tracy A. Stein ’92 25,000 47,423 Jeff Horner Memorial – 12,700 Ernest E. Monrad – 456,039 Thatcher A. Stone 20,000 244,141 David and Noreen Mulliken 25,000 1,980,221 Janet Schwitzer Nolan ’89 and Paul B. Nolan ’89 13,000 27,633 Endowed Unrestricted Funds James A. Pardo, Jr. ’79 and Mary C. Pardo 10,000 21,577 Jessica S. and James J. Benjamin Jr. ’90 Family $ 25,000 $ 25,037 Phipps Family 10,000 15,639 J. Goodwin Bland ’87 - Michael Katovitz 20,000 42,937 Deirdre and Pat Quinn Family 10,000 21,468 Board of Trustees Leadership Fund – 84,156 Donald Richberg – 351,233 Arnold R. Boyd – 1,024,977 Robertson Family 39,951 39,533 Andre W. Brewster ’48 Memorial – 294,316 William H.D. Rossiter – 6,303,078 Jack P. Brickman ’49 and Fay Cohen Brickman 40,000 39,958 Rutherfurd Family 5,000 48,084 E. Fontaine Broun – 1,623,703 JER – 116,602 Professor Leslie Buckler 139,897 146,395 David P. Saunders ’07 and Heidi Saunders 10,000 15,785 David C. -

8 University of Virginia School of Law

RANK 8 University of Virginia School of Law MAILING ADDRESS1-4 REGISTRAR’S PHONE 580 Massie Road 434-924-4122 Charlottesville, VA 22903-1738 ADMISSIONS PHONE MAIN PHONE 434-924-7351 (434) 924-7354 CAREER SERVICES PHONE WEBSITE 434-924-7349 www.law.virginia.edu Overview5 Founded by Thomas Jefferson in 1819, the University Of Virginia School Of Law is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants. Consistently ranked among the top law schools in the nation, Virginia has educated generations of lawyers, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service. Virginia is justly famous for its collegial environment that bonds students and faculty, and student satisfaction is consistently cited as among the highest in American law schools. At Virginia, law students share their experiences in a cooperative spirit, both in and out of the classroom, and build a network that lasts well beyond their three years here. Student-Faculty Ratio6 11.3:1 Admission Criteria7 LSAT GPA 25th–75th Percentile 164-170 3.52-3.94 Median* 169 3.87 Law School Admissions details based on 2013 data. *Medians have been calculated by averaging the 25th- and 75th-percentile values released by the law schools and have been rounded up to the nearest whole number for LSAT scores and to the nearest one-hundredth for GPAs. THE 2016 BCG ATTORNEY SEARCH GUIDE TO AMERICA’S TOP 50 LAW SCHOOLS 1 Admission Statistics7 Approximate number of applications 6048 Number accepted 1071 Acceptance rate 17.7% The above admission details are based on 2013 data. -

A Modest Proposal ...Hardy Cross Dillard

President’s Page ................................................. Jesse B. Wilson, III 2 The Battered Image of the Lawyer-- A Modest Proposal .................................... Hardy Cross Dillard The "Plain English" Trust .................................. J. Rodney Johnson 11 The Proposed Revision o[ UCC Article Eight .................................... Andrew W. McThenia, Jr. 15 A Brief Introduction to Qualified Employee Pension Plans ............................... Louis .4. Mezzullo 19 The Good Samaritan in Virginia 22 Law Reform: Virginia’s Alcohol Safety Action Program ........................................... B. Waugh Crigler 27 31 THE VIRGINIA BAR ASSOCIATION OFFICERS AND EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE President Past President Jesse B. Wilson, III Edward R. Slaughter, Jr. 4069 Chain Bridge Road P.O. Box 1191 Fairfax, Virginia 22030 Charlottesville, Virginia 22902 President-Elect Secretary- Treasurer L. Lee Bean A. Ward Sims 2045 15th Street, North P.O. Box 1029 Arlington, Virginia 22201 charlottesville, Virginia 22902 Chairman, Young Lawyers Section Chairman-Elect, Young Lawyers Section David Craig Landin Charles F. Midkiff P.O. Box 1191 1200 Mutual Building Charlottesville, Virginia 22902 Richmond, Virginia 23219 Director of Committee Activities John Ritchie P.O. Box 5206 Charlottesville, Virginia 22905 Executive Committee (Other than Ex-Officio Members) Hugh L. Patterson, Chairman Kenneth S. White Lewis M. Costello 1800 Virginia National Bank Bldg. P. O. Box 958 Box 2760 Norfolk, Virginia 23510 Lynchburg, Virginia 24505 Winchester, Virginia 22601 Robert P. Buford John F. Kay, Jr. Thomas R. Watkins 707 East Main Street P. O. Box 1122 Tower Box 60 1 lth Floor Richmond, Virginia 23208 2101 Executive Drive Richmond, Virginia 23212 Hampton, Virginia 23666 Gerald L. Baliles John L. Walker, Jr. John C. Wood P. O. Box 1640 P. O. Box 720 P. -

December 16, 1969 HON. WILLIAM B. SPONG

December 16, 1969 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 39509 to the Committee on Post Office and Civll Mr. TUNNEY, Mr. FRIEDEL, and Mr. for 2 months the authority to limit the Service. GILBERT): rates of interest or dividends payable on By Mr. BRADEMAS (for himself, Mr. H.R. 15290. A bill to authorize the U.S. time and savings deposits and accounts; to PERKINs, Mr. SCHEUER, Mr. REID of Commissioner of Education to establish the Committee on Banking and Currency. New York, Mr. HANSEN of Idaho, educational programs to encourage under By Mr. FISH: Mrs. MINK, Mr. DELLENBACK, Mr. standing of policies and support of activ H .J. Res. 1035. Joint resolution proposing WILLIAM D. FORD, Mr. MEEDs, Mr. ities designed to enhance environmental an amendment to the Constitution of the THOMPSON of New Jersey, Mr. DENT, quality and maintain ecological balance; to United States relative to equal rights for Mr. HATHAWAY, Mr. O'HARA, Mr. the Committee on Education and Labor. men and women; to the Committee on Ju GAYDOS, Mr. HELSTOSKI, Mr. MORSE, By Mr. BRASCO: diciary. Mr. HAwKINs, Mr. STOKEs, Mr. Hos H.R. 15291. A bill to amend title XVIII of By Mr. DAWSON: MER, Mr. CLAY, Mr. MAcGREGOR, Mr. the Social Security Act to provide payment H. Res. 752. Resolution providing for the HAMILTON, Mr. WHITEHURST, and for chiropractors' services under the program expenses of conducting studies and inves Mr. YATES): of supplementary medical insurance benefits tigations authorized by rule XI(8) incurred H.R. 15288. A bill to authorize the U.S. for the aged; to the Committee on Ways and by the Committee on Government Opera Commissioner of Education to establish edu Means. -

American Journal of International Law

AMERICAN JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW VOLUME 76 CONTENTS 1982 [No. 1, January 1982, pp. 1-230; No. 2, April 1982, pp. 231-475; No. 3, July 1982, pp. 477-715; No. 4, October 1982, pp. 717-960.] PAGE The Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea: The Tenth Session (1981) Bernard H. Oxman 1 U.S. Fishery Management and the New Law of the Sea W. T. Burke 24 Satellite Communication and Spectrum Allocation Martin A. Rothblatt 56 Technology and International Negotiations Jonathan I. Charney 78 The Inter-American Court of Human Rights Thomas Buergenthal 231 Conditioning U.S. Security Assistance on Human Rights Practices Stephen B. Cohen 246 Extraterritorial Jurisdiction at a Crossroads: An Intersection Between Public and Private International Law Harold G. Maier 280 The Torres Strait Treaty: Ocean Boundary Delimitation by Agreement H. Burmester 321 Recent Developments in United Nations Treaty Registration and Publication Practices Mala Tabory 350 The Grotian Vision of World Order Cornelius F. Murphy, Jr. 477 Contempt, Crisis, and the Court: The World Court and the Hostage Rescue Attempt Ted L. Stein 499 The Egyptian-Israeli Peace Treaty and Access to the Gulf of Aqaba: A New Legal Regime Mohamed ElBaradei 532 Sea Boundary Delimitation Between States Before World War II Sang-Myon Rhee 555 Discontinuance of International Proceedings: The Hostages Case Gerhard Wegen 717 The Plaintiff's Dilemma: Illegally Obtained Evidence and Admissibility in International Adjudication W. Michael Reisman & Eric E. Freedman 737 Norm Making and Supervision in International Human Rights: Reflections on Institutional Order Theodor Meron 754 The Law Governing Treaty Relations between Parties to the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties and States Not Party to the Convention E. -

Statement of Accounts July 1, 2017 – June 30, 2018

STATEMENT OF ACCOUNTS JULY 1, 2017 – JUNE 30, 2018 2017–2018 June 30, 2018 2017–2018 June 30, 2018 CONTRIBUTIONS MARKET VALUE CONTRIBUTIONS MARKET VALUE I. UNRESTRICTED FUNDS Warner Family $ – $ 410,789 Non-Endowed Unrestricted Funds Leigh D. Williams – 910,867 Current Use $ 4,109,447 $ 11,505,248 George A. and Elisabeth Dent Wilson – 19,861,612 Ernest L. Folk III 1,000 2,750 Stephen Clark Woodroe – 1,559,388 General Academic Programs – 3,515,611 Total Unrestricted Funds $ 4,892,609 $ 101,234,829 Jeff Horner Memorial – 12,700 Thatcher A. Stone 37,500 209,141 II. UNRESTRICTED REUNION FUNDS Class of 1968 Reunion $ 231,586 $ – Endowed Unrestricted Funds Class of 1978 Reunion 127,758 – Arnold R. Boyd $ – $ 1,029,878 Class of 1993 Reunion 145,698 – Andre W. Brewster ’48 Memorial – 295,724 Class of 2003 Reunion 57,834 – E. Fontaine Broun – 1,631,467 Class of 2008 Reunion 39,651 – David C. Burke ’93 100,000 100,000 Class of 2013 Reunion 15,413 – Andrew D. Christian – 41,252 Total Unrestricted Reunion Funds $ 617,940 $ – Class of 1929 – 352,092 Class of 1957 14,797 320,159 III. PROFESSORSHIPS Class of 1961 31,619 1,779,729 John S. Battle $ – $ 481,251 Class of 1973 159,255 166,810 Thomas F. Bergin Teaching 1,550 1,155,836 Lammot duPont Copeland – 7,474,819 Barron F. Black Research – 903,566 Richard N. Crockett – 145,149 Perre Bowen Fund – 4,267,403 Hardy Cross Dillard – 361,650 T. Munford Boyd 200 1,206,853 Henry L. -

History of Honors Conferred by the American Society of International

AMERICAN SOCIETY OF INTERNATIONAL LAW Regulation on the Honors Committee The Honors Committee shall make recommendations to the Executive Council with respect to the Society’s three annual awards: the Manley O. Hudson Medal, given to a distinguished person of American or other nationality for outstanding contributions to scholarship and achievement in international law; the Goler T. Butcher Medal, given to a distinguished person of American or other nationality for outstanding contributions to the development or effective realization of international human rights law; and the Honorary Member Award, given to a person of American or other nationality who has rendered distinguished contributions or service in the field of international law. (Note: Until 2015, the award was permitted to be given only to a non-American) RECIPIENTS OF THE MANLEY O. HUDSON MEDAL (†Deceased) 1956 Manley O. Hudson† 1989 Not awarded 1957 Not awarded 1990 Not awarded 1958 Not awarded 1991 Not awarded 1959 Lord McNair† 1992 Not awarded 1960 Not awarded 1993 Sir Robert Y. Jennings† 1961 Not awarded 1994 Not awarded 1962 Not awarded 1995 Louis Henkin† 1963 Not awarded 1996 Louis B. Sohn† 1964 Philip C. Jessup† 1997 John R. Stevenson† 1965 Not awarded 1998 Rosalyn Higgins 1966 Charles De Visscher† 1999 Shabtai Rosenne† 1967 Not awarded 2000 Stephen M. Schwebel 1968 Not awarded 2001 Prosper Weil† 1969 Not awarded 2002 Thomas Buergenthal 1970 Paul Guggenheim† 2003 Thomas M. Franck† 1971 Not awarded 2004 W. Michael Reisman 1972 Not awarded 2005 Elihu Lauterpacht† 1973 Not awarded 2006 Theodor Meron 1974 Not awarded 2007 Andreas Lowenfeld† 1975 Not awarded 2008 John Jackson† 1976 Myres McDougal† 2009 Charles N. -

Clark Hall, UVA Albemarle County, Virginia

NPS Form 10- 900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. Aug. 2002) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinaions for individual properties and districts. See instructions irv-low to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Fonn(National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the iQtmation requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "NIA" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instrutions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. ============================================================--===================---=======--- 1. Name of Property =================================================----=================--=========------======= historic name _ ___:::C~la::.!.r.:.::k...:.H..:.:a::.!1.:....1------------- other names/site number Clark Memorial Hall; University of Virginia School of Law; #002-5149 =================================================------==========================-============ 2. Location ============================================================================================== street & number 291 McCormick Road not for publication N/A city or town Charlottesville -

ITLOS Functions Primarily According to Rules Characteristic to the Civil Legal

Forum Shopping for the Best Adjudicator: Conflict Management and the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea Emilia Justyna Powell Department of Political Science University of Notre Dame [email protected] Sara McLaughlin Mitchell Department of Political Science University of Iowa [email protected] Abstract: This paper analyzes states’ selection of dispute settlement procedures in the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. Article 287 of the UNCLOS treaty stipulates that states may choose one of four compulsory procedures: 1) the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS), 2) the International Court of Justice (ICJ), 3) arbitration under Annex VII of the UNCLOS treaty or 4) arbitration under Annex VIII of the UNCLOS treaty. The authors argue that the dispute resolution procedures of the UNCLOS regime incorporate common law countries’ desire for flexibility in conflict management. Common law countries prefer the multiplicity of options and the default procedure of arbitration, especially given their resistance to the use of the ICJ as the primary adjudicator for resolving maritime conflicts. This flexibility in the UNCLOS dispute settlement procedures results in a higher level of ratification (or accession) of the UNCLOS treaty by common law states relative to civil law, Islamic law, and mixed law states. On the other hand, civil law countries ratifying the treaty are most likely to select the ICJ court as their preferred conflict management forum because the ICJ’s design is similar to civil law. Civil law countries are also more likely to select the ITLOS court and the Annex VII/VIII arbitration mechanisms than states with other domestic legal traditions.