The Morality of Compulsory Licensing As an Access to Medicines Tool

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Class of 2003 Finals Program

School of Law One Hundred and Seventy-Fourth FINAL EXERCISES The Lawn May 18, 2003 1 Distinction 2 High Distinction 3 Highest Distinction 4 Honors 5 High Honors 6 Highest Honors 7 Distinguished Majors Program School of Law Finals Speaker Mortimer M. Caplin Former Commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service Mortimer Caplin was born in New York in 1916. He came to Charlottesville in 1933, graduating from the College in 1937 and the Law School in 1940. During the Normandy invasion, he served as U.S. Navy beachmaster and was cited as a member of the initial landing force on Omaha Beach. He continued his federal service as Commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service under President Kennedy from 1961 to 1964. When he entered U.Va. at age 17, Mr. Caplin committed himself to all aspects of University life. From 1933-37, he was a star athlete in the University’s leading sport—boxing—achieving an undefeated record for three years in the mid-1930s and winning the NCAA middleweight title in spite of suffering a broken hand. He also served as coach of the boxing team and was president of the University Players drama group. At the School of Law, he was editor-in-chief of the Virginia Law Review and graduated as the top student in his class. In addition to his deep commitment to public service, he is well known for his devotion to teaching and to the educational process and to advancing tax law. Mr. Caplin taught tax law at U.Va. from 1950-61, while serving as president of the Atlantic Coast Conference. -

Circular 73B Compulsory License for Making and Distributing Digital Phonorecords

CIRCULAR 73B Compulsory License for Making and Distributing Digital Phonorecords and Limitations on Liability Prior to the License Availability Date (January 21, 2021) Copyright law provides a compulsory Under section 115 of the Copyright Act, an individual or license for making and distributing entity, subject to certain terms and conditions, may make digital phonorecord deliveries (DPDs) of nondramatic musi- phonorecords of certain nondramatic cal works if they have already been distributed as phonore- musical works. This circular addresses cords to the public in the United States under the authority of the copyright owner. When this condition does not exist, a the compulsory license for digital digital music provider may still make and distribute a DPD phonorecord deliveries (DPDs) and of a musical work if it satisfies three criteria: limitation on liability for making DPDs 1. the first fixation of the sound recording embodied in available prior to January 1, 2021. the DPD was made under the authority of the musical work copyright owner; It covers: 2. the sound recording copyright owner has the author- • When a compulsory license ity of the musical work copyright owner to make and can be used distribute digital phonorecord deliveries of such musi- cal work to the public; and • Activities covered by the compulsory 3. the sound recording copyright owner authorizes license and limitation on liability the digital music provider to make and distribute • Eligibility for limitation on liability digital phonorecord deliveries of the sound record- • When royalties must be paid ing to the public. For information on the compulsory NOTE: A nondramatic musical work is an original work of license for non-DPD phonorecords, authorship consisting of music—the succession of pitches and rhythm—and any accompanying lyrics not created for see Compulsory License for Making use in a motion picture or dramatic work. -

Compulsory Licensing of Musical Compositions for Phonorecords Under the Copyright Act of 1976 Paul S

Hastings Law Journal Volume 30 | Issue 3 Article 7 1-1979 Compulsory Licensing of Musical Compositions for Phonorecords under the Copyright Act of 1976 Paul S. Rosenlund Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Paul S. Rosenlund, Compulsory Licensing of Musical Compositions for Phonorecords under the Copyright Act of 1976, 30 Hastings L.J. 683 (1979). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol30/iss3/7 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Compulsory Licensing of Musical Compositions for Phonorecords Under the Copyright Act of 1976 By PaulS. Rosenlund* In 1976, Congress revised the copyright law of the United States for the first time in sixty-seven years.' As in 1909, when the previous copyright law was passed, one of the more controversial subjects of the 1976 Act was compulsory licensing of musical compositions for repro- duction in sound recordings. Basically, compulsory licensing under both the 1909 and 1976 Acts requires a music publisher to license a record company to manufacture and distribute phonorecords of most copyrighted music. To obtain such a license, a record company need only follow certain notice procedures and pay the modest mechanical 2 royalty specified in the compulsory licensing statute. The procedures which governed the availability and operation of compulsory licenses under the 1909 Act were unnecessarily burden- some on both copyright proprietors and the recording industry. -

Kendrick CV 2021-4.2

LESLIE CAROLYN KENDRICK University of Virginia School of Law Charlottesville, VA 22903 [email protected] EMPLOYMENT UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA SCHOOL OF LAW, Charlottesville, Virginia Vice Dean, July 2017-present White Burkett Miller Professor of Law and Public Affairs, August 2020-present David H. Ibbeken ’71 Research Professor of Law Professor of Law, August 2018-present Albert Clark Tate, Jr., Research Professor of Law, August 2014-August 2017 Professor of Law, 2013-2020 Associate Professor of Law, 2008-2013 HARVARD LAW SCHOOL, Cambridge, Massachusetts VisitinG Professor of Law, January 2017 UCLA SCHOOL OF LAW, Los Angeles, California VisitinG Professor of Law, January 2013-May 2013 THE HONORABLE DAVID H. SOUTER, Supreme Court of the United States Law Clerk, July 2007-July 2008 THE HONORABLE J. HARVIE WILKINSON, III, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit Law Clerk, June 2006-June 2007 EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA SCHOOL OF LAW, Charlottesville, Virginia J.D., May 2006 Hardy Cross Dillard Scholarship (full merit scholarship) UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD, Magdalen College, Oxford, UK D.Phil., English Literature, November 2003 M.Phil. with Distinction, English Literature, June 2000 Rhodes Scholarship (Kentucky & Magdalen 1998) UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHAPEL HILL, Chapel Hill, North Carolina B.A. with Highest Distinction, Classics and English, May 1998 Morehead Scholarship (full merit scholarship) Kendrick, 2 of 7 HONORS AND AWARDS Elected to American Law Institute (2017) University of Virginia All-University Teaching Award (2017) Carl McFarland Prize (for outstanding research by a junior member of UVA law faculty, 2014) Margaret G. Hyde Award (highest award given to member of graduating class at UVA Law, 2006) Virginia State Bar Family Law Book Award (2006) Judge John R. -

Philip C. Jessup Papers a Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress

Philip C. Jessup Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2003 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Catalog Record: https://lccn.loc.gov/mm78027771 Additional search options available at: https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms004004 Prepared by Allen H. Kitchens and Audrey Walker Revised and expanded by Connie L. Cartledge with the assistance of Michael W. Giese and Susie H. Moody Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Manuscript Division, 2004 Revised 2010 April Collection Summary Title: Philip C. Jessup Papers Span Dates: 1574-1983 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1925-1983) ID No.: MSS27771 Creator: Jessup, Philip C. (Philip Caryl), 1897-1986 Extent: 120,000 items Extent: 394 containers plus 2 oversize and 1 classified Extent: 157.6 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. LC Catalog record: https://lccn.loc.gov/mm78027771 Summary: Jurist, diplomat, and educator. Family and general correspondence, reports and memoranda, speeches and writings, subject files, legal papers, newspaper clippings and other papers pertaining chiefly to Jessup's work with the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Institute of Pacific Relations, United States Department of State, United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration, and International Court of Justice. Includes material relating to his World War I service in Spartanburg, S.C., and in France; and to charges made against him by Senator Joseph McCarthy and postwar loyalty and security investigations. Also includes papers of his wife, Lois Walcott Kellogg Jessup, relating to her work for the American Friends Service Committee, United States Children's Bureau, and United Nations, her travels to Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East, and to her writings. -

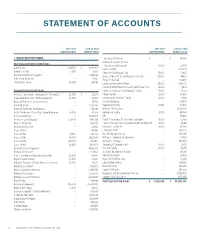

Statement of Accounts

STATEMENT OF ACCOUNTS 2019–2020 June 30, 2020 2019–2020 June 30, 2020 CONTRIBUTIONS MARKET VALUE CONTRIBUTIONS MARKET VALUE I. UNRESTRICTED FUNDS Lawrence W. I’Anson $ – $ 88,958 Michael R. Lincoln ’91 and Non–Endowed Unrestricted Funds Wendy Lavalle Lincoln 10,000 20,725 Current Use $ 4,249,758 $ 3,914,923 Henry C. Little – 1,104,129 Ernest L. Folk III 1,000 4,750 Deborah Platt Majoras ’89 15,000 31,835 General Academic Programs – 2,817,534 Marco V. Masotti ’92 and Tracy A. Stein ’92 25,000 47,423 Jeff Horner Memorial – 12,700 Ernest E. Monrad – 456,039 Thatcher A. Stone 20,000 244,141 David and Noreen Mulliken 25,000 1,980,221 Janet Schwitzer Nolan ’89 and Paul B. Nolan ’89 13,000 27,633 Endowed Unrestricted Funds James A. Pardo, Jr. ’79 and Mary C. Pardo 10,000 21,577 Jessica S. and James J. Benjamin Jr. ’90 Family $ 25,000 $ 25,037 Phipps Family 10,000 15,639 J. Goodwin Bland ’87 - Michael Katovitz 20,000 42,937 Deirdre and Pat Quinn Family 10,000 21,468 Board of Trustees Leadership Fund – 84,156 Donald Richberg – 351,233 Arnold R. Boyd – 1,024,977 Robertson Family 39,951 39,533 Andre W. Brewster ’48 Memorial – 294,316 William H.D. Rossiter – 6,303,078 Jack P. Brickman ’49 and Fay Cohen Brickman 40,000 39,958 Rutherfurd Family 5,000 48,084 E. Fontaine Broun – 1,623,703 JER – 116,602 Professor Leslie Buckler 139,897 146,395 David P. Saunders ’07 and Heidi Saunders 10,000 15,785 David C. -

Study 5: the Compulsory License Provisions of the U.S. Copyright

86th CODgrMII} 1st 8eBaion CO~TTEE PB~ COPYRIGHT LAW REVISION 1 STUDIES PREPARED FOR THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON PATENTS, TRADEMARKS, AND COPYRIGHTS OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE EIGHTY-SIXTH CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION PURSUANT TO S. Res. 53 STUDIES 5-6 5. The Compulsory License Provisions of the U.S. Copyright Law 6. The Economic Aspects of the Compulsory License .. Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary --f UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASIDNGTON : 1960 I , COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY JAMES O. EASTLAND, Mississippi, Chairman ESTES KEFAUVER, Tennessee ALEXANDER WILEY, Wisconsin OLIN D. JOHNSTON, South Carolina WILLIAM LANGER, North Dakota I THOMAS C. HENNINGS, JR., Missouri EVERETT McKINLEY DIRKSEN, Illinois JOHN L. McCLELLAN, ArkansllS ROMAN L. HRUSKA, Nebraska JOSEPH C. O'MAHONEY, Wyoming KENNETH B. KEATING, New York SAM J. ERVIN, JR., North Carolina JOHN A. CARROLL, Colorado THOMAS J. DODD, Connecticut PHILIP A. HART, Michigan SUBCOMMITTEE ON PATENTS, TRADEMARKS, AND COPYRIGHTS JOSEPH C. O'MAHONEY, Wyoming, Chairman OLIN D. JOHNSTON, South Carolina ALEXANDER WILEY, Wisconsin PHILIP A, HART, Michigan ROBERT L. WRIGHT, CAie! Coumel JOHN C. STEDMAN, Alloclate Coumd STEPHEN G. HUBER, C,lile! Cler"k 1 The late Honorable WllUam Langer, whUe a member_of this committee, dIed on Nov. 8, 1959. n , FOREWORD This is the second of a series of committee prints to be published by the Committee on the Judiciary Subcommittee on Patents, Trade marks, and Copyrights presenting studies prepared under the super vision of the Copyright Office of the Library of Congress with a view to considering a general revision of the copyright law (title 17, United States Code). -

8 University of Virginia School of Law

RANK 8 University of Virginia School of Law MAILING ADDRESS1-4 REGISTRAR’S PHONE 580 Massie Road 434-924-4122 Charlottesville, VA 22903-1738 ADMISSIONS PHONE MAIN PHONE 434-924-7351 (434) 924-7354 CAREER SERVICES PHONE WEBSITE 434-924-7349 www.law.virginia.edu Overview5 Founded by Thomas Jefferson in 1819, the University Of Virginia School Of Law is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants. Consistently ranked among the top law schools in the nation, Virginia has educated generations of lawyers, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service. Virginia is justly famous for its collegial environment that bonds students and faculty, and student satisfaction is consistently cited as among the highest in American law schools. At Virginia, law students share their experiences in a cooperative spirit, both in and out of the classroom, and build a network that lasts well beyond their three years here. Student-Faculty Ratio6 11.3:1 Admission Criteria7 LSAT GPA 25th–75th Percentile 164-170 3.52-3.94 Median* 169 3.87 Law School Admissions details based on 2013 data. *Medians have been calculated by averaging the 25th- and 75th-percentile values released by the law schools and have been rounded up to the nearest whole number for LSAT scores and to the nearest one-hundredth for GPAs. THE 2016 BCG ATTORNEY SEARCH GUIDE TO AMERICA’S TOP 50 LAW SCHOOLS 1 Admission Statistics7 Approximate number of applications 6048 Number accepted 1071 Acceptance rate 17.7% The above admission details are based on 2013 data. -

United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit

Case: 20-1758 Document: 31 Page: 1 Filed: 08/31/2020 No. 20-1758 IN THE United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit JUNO THERAPEUTICS, INC., SLOAN KETTERING INSTITUTE FOR CANCER RESEARCH, Plaintiffs-Appellees, v. KITE PHARMA, INC., Defendant-Appellant. On Appeal from the United States District Court for the Central District of California No. 2:17-cv-07639-PSG-KS Hon. Philip S. Gutierrez NONCONFIDENTIAL OPENING BRIEF AND ADDENDUM FOR KITE PHARMA, INC. Jeffrey I. Weinberger E. Joshua Rosenkranz Ted G. Dane ORRICK, HERRINGTON & Garth T. Vincent SUTCLIFFE LLP Peter E. Gratzinger 51 West 52nd Street Adam R. Lawton New York, NY 10019 MUNGER, TOLLES & OLSON LLP (212) 506-5000 350 S. Grand Ave., 50th floor Los Angeles, CA 90071 Melanie L. Bostwick Jeremy Peterman Geoffrey D. Biegler Robbie Manhas FISH & RICHARDSON, P.C. ORRICK, HERRINGTON & 12390 El Camino Real, Ste. 100 SUTCLIFFE LLP San Diego, CA 92130 1152 15th Street NW Washington, DC 20005 Grant T. Rice FISH & RICHARDSON, P.C. One Marina Park Drive Boston, MA 02210 Counsel for Defendant-Appellant Case: 20-1758 Document: 31 Page: 2 Filed: 08/31/2020 U.S. PATENT NO. 7,446,190: CLAIMS 1-3, 5, 7-9, AND 11 (CLAIMS 3, 5, 9, AND 11 ASSERTED) 1. A nucleic acid polymer encoding a chimeric T cell receptor, said chimeric T cell receptor comprising (a) a zeta chain portion comprising the intracellular domain of human CD3 ζ chain, (b) a costimulatory signaling region, and (c) a binding element that specifically interacts with a selected target, wherein the costimulatory signaling region comprises the amino acid sequence encoded by SEQ ID NO:6. -

Frand and Compulsory Licenses: Analysis and Comparison

Texas A&M University School of Law Texas A&M Law Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 2-2015 Frand and Compulsory Licenses: Analysis and Comparison Srividhya Ragavan Texas A&M University School of Law, [email protected] Raj S. Davé Pillsbury, Winthrop, Shaw, Pittman LLP, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Srividhya Ragavan & Raj S. Davé, Frand and Compulsory Licenses: Analysis and Comparison, 9-3 (2015). Available at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar/726 This Book Section is brought to you for free and open access by Texas A&M Law Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Texas A&M Law Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TRENDS IN LICENSING § 9.01[A] § 9.01 FRAND AND COMPULSORY LICENSES: ANALYSIS AND COMPARISON Srividhya Ragavan and Raj S. Davé [A] Introduction Licenses are important tools to capture the full market value of many of the intangible assets. In that, licenses serve an important function in all areas of intel- lectual property rights to effectively capitalize on the value of the property. Opera- tionally, intellectual property licenses are private agreements between two parties, one of whom will be the owner of the intellectual property, typically detailing the rights relating to the use, dissemination, development of the property. Especially in the area of patents, licenses are the most important tools deployed by the inven- tor to ensure that the technology is appropriately captured by the market. -

Frand V. Compulsory Licensing: the Lesser of the Two Evils † Srividhya Ragavan, Brendan Murphy, and Raj Davé

FRAND V. COMPULSORY LICENSING: THE LESSER OF THE TWO EVILS † SRIVIDHYA RAGAVAN, BRENDAN MURPHY, AND RAJ DAVÉ ABSTRACT This paper focuses on two types of licenses that can best be described as outliers—FRAND and compulsory licenses. Overall, these two specific forms of licenses share the objective of producing a fair and reasonable license of a technology protected by intellectual property. The comparable objective notwithstanding, each type of license achieves this end using different mechanisms. The FRAND license emphasizes providing the licensee with reasonable terms, e.g., by preventing a standard patent holder from extracting unreasonably high royalty rates. By contrast, compulsory licenses emphasize the public benefit that flows from enabling access to an otherwise inaccessible invention. Ultimately, both forms of license attempt to create a value for the licensed product that can be remarkably different from the product’s true market value. Nevertheless, both forms ultimately benefit the end-consumer who pays less to access a product subject to either of these forms of license. In comparing these two forms of licenses, the paper hopes to determine whether one form is better than the other, and if so, from whose perspective—the consumer, the licensor or the licensee. In doing so, this paper compares the different prevailing efforts to embrace such licenses as well as the impact of such licenses on the industry. INTRODUCTION Licenses are specific forms of contract structured as legal tools detailing the terms of a bargain to either gain or give away rights in exchange for other interests or obligations. Licenses are used in different situations and for using different technologies to create and define rights of the involved parties. -

Patent-Based Open Science

Maine Law Review Volume 59 Number 2 Symposium: Closing in on Open Science: Article 6 Trends in Intellectual Property & Scientific Research June 2007 Road Map to Revolution? Patent-Based Open Science Lee Petherbridge Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mainelaw.maine.edu/mlr Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation Lee Petherbridge, Road Map to Revolution? Patent-Based Open Science, 59 Me. L. Rev. 339 (2007). Available at: https://digitalcommons.mainelaw.maine.edu/mlr/vol59/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Maine School of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Maine School of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ROAD MAP TO REVOLUTION? PATENT-BASED OPEN SCIENCE Lee Petherbridge, Ph.D I. INTRODUCTION II. A TOPOGRAPHY OF INNOVATION AND LAW IN THE LIFE SCIENCES A. The Industrial Infrastructure: Integrating Public and Private Science B. The Legal Infrastructure: A Proprietary Approach I. The Innovation Suppressive Cost of Monopoly 2. Additional Innovation Suppressive Costs III. A THEORY OF OPEN LIFE SCIENCE A. Open Science B. To Open Science from Open Source I. Addressing Fixed Costs 2. Peer Worker Potential 3. Issues of Modularity and Granularity 4. Subsequent (Mis)appropriation IV. TOWARD A PATENT-BASED OPEN SCIENCE FRAMEWORK A. Establishing a Patent Servitude B. Patent Servitudes in Operation C. Additional Considerations V. CONCLUDING REMARKS HeinOnline -- 59 Me. L. Rev. 339 2007 340 MAINE LAW REVIEW [Vol.