Clark Hall, UVA Albemarle County, Virginia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A* ACE Study, See Student Body

UVA CLIPPINGS FILE SUBJECT HEADINGS *A* Anderson, John F. Angress, Ruth K, A.C.E. Study, see Student body – Characteristics Anthropology and Sociology, Dept. of A.I.D.S. Archaeology Abbott, Charles Cortez Abbott, Francis Harris Archer, Vincent Architecture - U.Va. and environs, see also Local History File Abernathy, Thomas P. Architecture, School of Abraham, Henry J. Art Department Academic costume, procession, etc. Arts and Sciences - College Academical Village, see Residential Colleges Arts and Sciences - Graduate School Accreditation, see also Self Study Asbestos removal, see Waste Accuracy in Academia Adams (Henry) Papers Asian Studies Assembly of Professors Administration and administrative Astronomy Department committees (current) Athletics [including Intramurals] Administration - Chart - Academic Standards, scholarships, etc. Admissions and enrollment – to 1970\ - Baseball - 1970-1979 - Basketball - 1980- - Coaches - In-state vs. out-of-state - Fee - S.A.T. scores see also Athletes - Academic standards - Football - Funding Blacks - Admission and enrollment - Intercollegiate aspects Expansion - Soccer Women- Admission to UVA - Student perceptions Aerospace engineering, see Engineering, Aerospace see also names of coaches Affirmative Action, Office of Afro-American, Atomic energy, see Engineering, Nuclear see Blacks - Afro-American… Attinger, Ernst O. AIDS, see A.I.D.S. Authors Alcohol, see also Institute/ Substance Abuse Studies Alden, Harold Automobiles Aviation Alderman Library, see Library, Alderman Awards, Honors, Prizes - Directory Alderman, Edwin Anderson – Biography - Obituaries *B* - Speeches, papers, etc. Alderman Press Baccalaureate sermons, 1900-1953 Alford, Neill H., Jr. Bad Check Committee Alumni activities Baker, Houston A., Jr. Alumni Association – local chapter Bakhtiar, James A.H. Alumni – noteworthy Balch lectures and awards American Assn of University Professors, Balfour addition, see McIntire School of Commerce Virginia chapter Ballet Amphitheater| Balz, A.G.A. -

Class of 2003 Finals Program

School of Law One Hundred and Seventy-Fourth FINAL EXERCISES The Lawn May 18, 2003 1 Distinction 2 High Distinction 3 Highest Distinction 4 Honors 5 High Honors 6 Highest Honors 7 Distinguished Majors Program School of Law Finals Speaker Mortimer M. Caplin Former Commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service Mortimer Caplin was born in New York in 1916. He came to Charlottesville in 1933, graduating from the College in 1937 and the Law School in 1940. During the Normandy invasion, he served as U.S. Navy beachmaster and was cited as a member of the initial landing force on Omaha Beach. He continued his federal service as Commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service under President Kennedy from 1961 to 1964. When he entered U.Va. at age 17, Mr. Caplin committed himself to all aspects of University life. From 1933-37, he was a star athlete in the University’s leading sport—boxing—achieving an undefeated record for three years in the mid-1930s and winning the NCAA middleweight title in spite of suffering a broken hand. He also served as coach of the boxing team and was president of the University Players drama group. At the School of Law, he was editor-in-chief of the Virginia Law Review and graduated as the top student in his class. In addition to his deep commitment to public service, he is well known for his devotion to teaching and to the educational process and to advancing tax law. Mr. Caplin taught tax law at U.Va. from 1950-61, while serving as president of the Atlantic Coast Conference. -

Virginia Law Review Online

COPYRIGHT © 2018 VIRGINIA LAW REVIEW ASSOCIATION VIRGINIA LAW REVIEW ONLINE VOLUME 104 JANUARY 2018 1–7 FOREWORD Farah Peterson∗ On August 11 and 12, 2017, neo-Nazis and Klansmen came to Charlottesville to hold a rally meant to assert themselves as a force in American society. That event, and the President’s reaction to it, raised the disturbing possibility that for the first time in more than fifty years, white supremacy could be a matter of debate at the highest levels of American politics. This Foreword asks what legal scholarship has to contribute in times like these. It also introduces a partial answer: a group of student and faculty pieces analyzing some of the many difficult legal questions the rally raised. * * * T’S hard to know where to begin the story that culminated in the Imurder of Heather Heyer and the injury to our body politic. It could start in the early twentieth century, when black service in WWI and the rhetoric of that war gave black Americans new hope and inspired them to new militancy in demanding eQual citizenship.1 These hopes, short-lived, were “smashed” by a “reaction of violence that was probably unprecedented.”2 The last six months of 1919 saw twenty-five race riots in American cities, north and south, in which “mobs took over cities for days at a time, flogging, burning, shooting, and torturing at will.”3 It was also in 1919, that Paul Goodloe McIntire, a one-time UVA attendee and a great university benefactor, dedicated the first of the four bronze statues he had * Associate Professor of Law, University of Virginia School of Law. -

Kendrick CV 2021-4.2

LESLIE CAROLYN KENDRICK University of Virginia School of Law Charlottesville, VA 22903 [email protected] EMPLOYMENT UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA SCHOOL OF LAW, Charlottesville, Virginia Vice Dean, July 2017-present White Burkett Miller Professor of Law and Public Affairs, August 2020-present David H. Ibbeken ’71 Research Professor of Law Professor of Law, August 2018-present Albert Clark Tate, Jr., Research Professor of Law, August 2014-August 2017 Professor of Law, 2013-2020 Associate Professor of Law, 2008-2013 HARVARD LAW SCHOOL, Cambridge, Massachusetts VisitinG Professor of Law, January 2017 UCLA SCHOOL OF LAW, Los Angeles, California VisitinG Professor of Law, January 2013-May 2013 THE HONORABLE DAVID H. SOUTER, Supreme Court of the United States Law Clerk, July 2007-July 2008 THE HONORABLE J. HARVIE WILKINSON, III, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit Law Clerk, June 2006-June 2007 EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA SCHOOL OF LAW, Charlottesville, Virginia J.D., May 2006 Hardy Cross Dillard Scholarship (full merit scholarship) UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD, Magdalen College, Oxford, UK D.Phil., English Literature, November 2003 M.Phil. with Distinction, English Literature, June 2000 Rhodes Scholarship (Kentucky & Magdalen 1998) UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHAPEL HILL, Chapel Hill, North Carolina B.A. with Highest Distinction, Classics and English, May 1998 Morehead Scholarship (full merit scholarship) Kendrick, 2 of 7 HONORS AND AWARDS Elected to American Law Institute (2017) University of Virginia All-University Teaching Award (2017) Carl McFarland Prize (for outstanding research by a junior member of UVA law faculty, 2014) Margaret G. Hyde Award (highest award given to member of graduating class at UVA Law, 2006) Virginia State Bar Family Law Book Award (2006) Judge John R. -

Philip C. Jessup Papers a Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress

Philip C. Jessup Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2003 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Catalog Record: https://lccn.loc.gov/mm78027771 Additional search options available at: https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms004004 Prepared by Allen H. Kitchens and Audrey Walker Revised and expanded by Connie L. Cartledge with the assistance of Michael W. Giese and Susie H. Moody Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Manuscript Division, 2004 Revised 2010 April Collection Summary Title: Philip C. Jessup Papers Span Dates: 1574-1983 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1925-1983) ID No.: MSS27771 Creator: Jessup, Philip C. (Philip Caryl), 1897-1986 Extent: 120,000 items Extent: 394 containers plus 2 oversize and 1 classified Extent: 157.6 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. LC Catalog record: https://lccn.loc.gov/mm78027771 Summary: Jurist, diplomat, and educator. Family and general correspondence, reports and memoranda, speeches and writings, subject files, legal papers, newspaper clippings and other papers pertaining chiefly to Jessup's work with the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Institute of Pacific Relations, United States Department of State, United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration, and International Court of Justice. Includes material relating to his World War I service in Spartanburg, S.C., and in France; and to charges made against him by Senator Joseph McCarthy and postwar loyalty and security investigations. Also includes papers of his wife, Lois Walcott Kellogg Jessup, relating to her work for the American Friends Service Committee, United States Children's Bureau, and United Nations, her travels to Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East, and to her writings. -

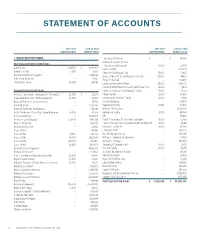

Statement of Accounts

STATEMENT OF ACCOUNTS 2019–2020 June 30, 2020 2019–2020 June 30, 2020 CONTRIBUTIONS MARKET VALUE CONTRIBUTIONS MARKET VALUE I. UNRESTRICTED FUNDS Lawrence W. I’Anson $ – $ 88,958 Michael R. Lincoln ’91 and Non–Endowed Unrestricted Funds Wendy Lavalle Lincoln 10,000 20,725 Current Use $ 4,249,758 $ 3,914,923 Henry C. Little – 1,104,129 Ernest L. Folk III 1,000 4,750 Deborah Platt Majoras ’89 15,000 31,835 General Academic Programs – 2,817,534 Marco V. Masotti ’92 and Tracy A. Stein ’92 25,000 47,423 Jeff Horner Memorial – 12,700 Ernest E. Monrad – 456,039 Thatcher A. Stone 20,000 244,141 David and Noreen Mulliken 25,000 1,980,221 Janet Schwitzer Nolan ’89 and Paul B. Nolan ’89 13,000 27,633 Endowed Unrestricted Funds James A. Pardo, Jr. ’79 and Mary C. Pardo 10,000 21,577 Jessica S. and James J. Benjamin Jr. ’90 Family $ 25,000 $ 25,037 Phipps Family 10,000 15,639 J. Goodwin Bland ’87 - Michael Katovitz 20,000 42,937 Deirdre and Pat Quinn Family 10,000 21,468 Board of Trustees Leadership Fund – 84,156 Donald Richberg – 351,233 Arnold R. Boyd – 1,024,977 Robertson Family 39,951 39,533 Andre W. Brewster ’48 Memorial – 294,316 William H.D. Rossiter – 6,303,078 Jack P. Brickman ’49 and Fay Cohen Brickman 40,000 39,958 Rutherfurd Family 5,000 48,084 E. Fontaine Broun – 1,623,703 JER – 116,602 Professor Leslie Buckler 139,897 146,395 David P. Saunders ’07 and Heidi Saunders 10,000 15,785 David C. -

Eugenics in America by Anne Legge

Torch Magazine • Fall 2018 Eugenics in America By Anne Legge In his wonderfully written D. Rockefeller, Alexander Graham book The Gene: An Intimate Bell, and Supreme Court Justice History, Pulitzer prize-winning Oliver Wendell Holmes. Not author Siddhartha Mukherjee himself a hard-core eugenicist, characterizes eugenics as a Charles Darwin acknowledged the “flirtation with the perfectibility need for altruism and aid for our of man” (12). An ingredient of weaker brothers and sisters, but the Progressive Movement in hard-core geneticists embraced the United States from 1890 to the thinking of Social Darwinism, The late Anne Legge was a retired 1930, eugenics was a response to questioning even vaccination and associate professor of English from Lord Fairfax Community College, the stresses of the time including philanthropy as factors that enable Middletown, Virginia. industrialization, immigration, the weaker to survive. and urbanization. Eugenics came She graduated Phi Beta Kappa from the College of William and in two varieties: positive eugenics Eugenics was inherently racist, Mary, where she was student encouraged breeding of desirable based on a belief in the superiority body president. She also earned a stock, and negative eugenics of Nordic stock and on preserving graduate degree from the University of Virginia. prevented reproduction of the unfit the purity of the “germ-plasm,” the (Cohen 47). The problem is who eugenicists’ term for the inheritance A member of the Winchester Torch decides who is “fit,” and by what package carried by individuals. The Club since 1983, she served as club president (1986-87) and received the criteria. By its very nature, eugenics national stock of germ-plasm was Silver Torch Award in 2001. -

Claude A. Swanson of Virginia: a Political Biography

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Political History History 1985 Claude A. Swanson of Virginia: A Political Biography Henry C. Ferrell Jr. East Carolina University Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Ferrell, Henry C. Jr., "Claude A. Swanson of Virginia: A Political Biography" (1985). Political History. 14. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_political_history/14 Claude A. Swanson Claude A. Swanson of Virginia A Political Biography HENRY C. FERRELL, Jr. THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this book has been assisted by a grant from East Carolina University Copyright© 1985 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine College, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Club, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. Editorial and Sales Offices: Lexington, Kentucky 40506-0024 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Ferrell, Henry C., 1934- Claude A. Swanson of Virginia. Bibliography: p. Includes index. I. Swanson, Claude Augustus, 1862-1939. 2. Legislators -United States-Biography. 3. United States. Congress Biography. 4. Virginia---Governors-Biography. I. Title. E748.S92F47 1985 975.5'042'0924 [B] 84-27031 ISBN: 978-0-8131-5243-1 To Martha This page intentionally left blank Contents Illustrations and Photo Credits vm Preface 1x 1. -

8 University of Virginia School of Law

RANK 8 University of Virginia School of Law MAILING ADDRESS1-4 REGISTRAR’S PHONE 580 Massie Road 434-924-4122 Charlottesville, VA 22903-1738 ADMISSIONS PHONE MAIN PHONE 434-924-7351 (434) 924-7354 CAREER SERVICES PHONE WEBSITE 434-924-7349 www.law.virginia.edu Overview5 Founded by Thomas Jefferson in 1819, the University Of Virginia School Of Law is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants. Consistently ranked among the top law schools in the nation, Virginia has educated generations of lawyers, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service. Virginia is justly famous for its collegial environment that bonds students and faculty, and student satisfaction is consistently cited as among the highest in American law schools. At Virginia, law students share their experiences in a cooperative spirit, both in and out of the classroom, and build a network that lasts well beyond their three years here. Student-Faculty Ratio6 11.3:1 Admission Criteria7 LSAT GPA 25th–75th Percentile 164-170 3.52-3.94 Median* 169 3.87 Law School Admissions details based on 2013 data. *Medians have been calculated by averaging the 25th- and 75th-percentile values released by the law schools and have been rounded up to the nearest whole number for LSAT scores and to the nearest one-hundredth for GPAs. THE 2016 BCG ATTORNEY SEARCH GUIDE TO AMERICA’S TOP 50 LAW SCHOOLS 1 Admission Statistics7 Approximate number of applications 6048 Number accepted 1071 Acceptance rate 17.7% The above admission details are based on 2013 data. -

Memorialization and Mission at UVA Our Grounds Should Embody Our History, Our Mission, and Our Values Submitted to President James E

Memorialization and Mission at UVA Our Grounds should embody our history, our mission, and our values Submitted to President James E. Ryan March, 2020 Memorialization on Grounds Committee Members: Garth Anderson, Facility Historian, Geospatial Engineering Services, Facilities Management James T. Campbell, Edgar E. Robinson Professor in US History, Stanford University Ishraga Eltahir, Col’ 2011 and founding Chair of Memorial for Enslaved Laborers Wesley L. Harris, CS Draper Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics, MIT Carmenita Higginbotham, Associate Professor and Art Department Chair Ervin L. Jordan, Jr., Associate Professor and Research Archivist, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library Phyllis K. Leffler, Professor Emerita of History Matthew McLendon, J. Sanford Miller Family Director and Chief Curator, The Fralin Museum of Art at the University of Virginia Louis Nelson (chair), Professor of Architectural History and Vice Provost for Academic Outreach Ashley Schmidt, Academic Program Officer, PCUAS Zaakir Tameez, Presidential Fellow, Office of President James Ryan Elizabeth R. Varon, Langbourne M. Williams Professor of American History Howard Witt, Director of Communications and Managing Editor, Miller Center PCUAS Co-Chairs: Andrea Douglas, Executive Director, Jefferson School African American Heritage Center Kirt von Daacke, Assistant Dean & Professor (History & American Studies) I. Introduction The University of Virginia’s mission statement, adopted by the Board of Visitors in 2013, makes clear UVA’s “unwavering support of a collaborative, diverse community bound together by distinctive foundational values of honor, integrity, trust, and respect.” Those values are conveyed through the policies the University enacts, the programs and courses it offers, the students it graduates, the faculty and staff it hires — and, not least, in the names the University inscribes above the entrances to its buildings and the people it honors with statuary and monuments. -

Journals That Publish Student Notes

Compiled by Syracuse Law Review Law Journals that Publish Student Notes Law Journals that Do NOT Publish Student Notes Albany Government Law Review Alabama Law Review Albany Law Journal of Science & Technology American Criminal Law Review Albany Law Review American University Law Review American Criminal Law Review Arizona State Law Journal Buffalo Intellectual Property Law Journal Baylor Law Review California Law Review Berkeley Technology Law Journal Chicanx-Latinx Law Review Boston College Intellectual Property & Technology Forum CUNY Law Review Boston College Law Review Dartmouth Law Journal Boston University Law Review DePaul Journal of Art, Technology, & Intellectual Property Cardozo Journal of Conflict Resolution DePaul Journal of Health Care Law Case Western Reserve Law Review DePaul Law Review Chicago Journal of International Law Drake Law Review Chicago Journal of International Law Florida A&M University Law Review Chicago-Kent Law Review Georgetown Journal of Gender and the Law Children's Legal Rights Journal Georgetown Journal of International Law Cleveland State Law Review Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics Colorado Law Review Georgetown Journal of Poverty Law & Policy Colorado Technology Law Journal Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review Columbia Business Law Review Harvard Journal of Law & Gender Columbia Human Rights Law Review Harvard Journal of Law & Technology~ Columbia Journal of Environmental Law Harvard Law & Policy Review Columbia Journal of Transnational Law Harvard Law National Security Journal Columbia -

CURRICULUM VITAE David A

CURRICULUM VITAE David A. Logan Office Home 10 Metacom Avenue 5 Cutter Lane Bristol, RI 02809 Tiverton, RI 02878 (401) 254-4501 (401) 418-9920 [email protected] Academic Appointments 2003-present Roger Williams University School of Law, Bristol, RI Dean (2003-2014), Professor of Law (2014-present) • Adviser, Restatement (Third) of Torts, Liability for Physical and Emotional Harm and Defamation and Privacy projects • Association of American Law Schools “Deborah Rhode Award for Public Service and Pro Bono Leadership” • Rhode Island Legal Services “Commitment to Justice Award” • National Association for the Advancement of Colored People-Rhode Island “Community Leadership Award” • Rhode Island for Community and Justice “Equal Justice Leadership Award” 1981-2003 Wake Forest University School of Law, Winston-Salem, NC • Student Bar Association “Teacher of the Year” • Chief Justice Joseph Branch “Faculty Excellence Award” Visiting Professorships: University of Arizona College of Law (spring 2017) Florida State College of Law (spring 2015) Brooklyn Law School (summer 2001) Santa Clara School of Law (summers 1997, 2000) New York Law School (summer 1999) University of North Carolina School of Law (spring 1996, 1995) University of Maine School of Law (summer 1995) Seattle University School of Law (summer 1994) University of Texas School of Law (summer 1992) Education J.D. 1977 University of Virginia School of Law, Charlottesville, VA • Chair, Moot Court Board • Hardy C. Dillard Fellow (1975-77) • Raven Society (university-wide academic and leadership honorary) M.A. 1972 University of Wisconsin-Madison • Fellow at the Center for Public Policy and Administration B.A. 1971 Bucknell University, Lewisburg, PA 1 • Pi Sigma Alpha (National Political Science Honorary) • Dean's List • Varsity basketball • Board of Directors and disc jockey WVBU-FM Selected Publications Rescuing our Democracy by Revisiting New York Times v.