Other Marine Envenomations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cobia Database Articles Final Revision 2.0, 2-1-2017

Revision 2.0 (2/1/2017) University of Miami Article TITLE DESCRIPTION AUTHORS SOURCE YEAR TOPICS Number Habitat 1 Gasterosteus canadus Linné [Latin] [No Abstract Available - First known description of cobia morphology in Carolina habitat by D. Garden.] Linnaeus, C. Systema Naturæ, ed. 12, vol. 1, 491 1766 Wild (Atlantic/Pacific) Ichthyologie, vol. 10, Iconibus ex 2 Scomber niger Bloch [No Abstract Available - Description and alternative nomenclature of cobia.] Bloch, M. E. 1793 Wild (Atlantic/Pacific) illustratum. Berlin. p . 48 The Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the Under this head was to be carried on the study of the useful aquatic animals and plants of the country, as well as of seals, whales, tmtles, fishes, lobsters, crabs, oysters, clams, etc., sponges, and marine plants aml inorganic products of U.S. Commission on Fisheries, Washington, 3 United States. Section 1: Natural history of Goode, G.B. 1884 Wild (Atlantic/Pacific) the sea with reference to (A) geographical distribution, (B) size, (C) abundance, (D) migrations and movements, (E) food and rate of growth, (F) mode of reproduction, (G) economic value and uses. D.C., 895 p. useful aquatic animals Notes on the occurrence of a young crab- Proceedings of the U.S. National Museum 4 eater (Elecate canada), from the lower [No Abstract Available - A description of cobia in the lower Hudson Eiver.] Fisher, A.K. 1891 Wild (Atlantic/Pacific) 13, 195 Hudson Valley, New York The nomenclature of Rachicentron or Proceedings of the U.S. National Museum Habitat 5 Elacate, a genus of acanthopterygian The universally accepted name Elucate must unfortunately be supplanted by one entirely unknown to fame, overlooked by all naturalists, and found in no nomenclator. -

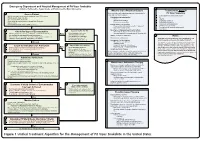

Snake Bite Protocol

Lavonas et al. BMC Emergency Medicine 2011, 11:2 Page 4 of 15 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-227X/11/2 and other Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center treatment of patients bitten by coral snakes (family Ela- staff. The antivenom manufacturer provided funding pidae), nor by snakes that are not indigenous to the US. support. Sponsor representatives were not present dur- At the time this algorithm was developed, the only ing the webinar or panel discussions. Sponsor represen- antivenom commercially available for the treatment of tatives reviewed the final manuscript before publication pit viper envenomation in the US is Crotalidae Polyva- ® for the sole purpose of identifying proprietary informa- lent Immune Fab (ovine) (CroFab , Protherics, Nash- tion. No modifications of the manuscript were requested ville, TN). All treatment recommendations and dosing by the manufacturer. apply to this antivenom. This algorithm does not con- sider treatment with whole IgG antivenom (Antivenin Results (Crotalidae) Polyvalent, equine origin (Wyeth-Ayerst, Final unified treatment algorithm Marietta, Pennsylvania, USA)), because production of The unified treatment algorithm is shown in Figure 1. that antivenom has been discontinued and all extant The final version was endorsed unanimously. Specific lots have expired. This antivenom also does not consider considerations endorsed by the panelists are as follows: treatment with other antivenom products under devel- opment. Because the panel members are all hospital- Role of the unified treatment algorithm -

Traveler Information

Traveler Information QUICK LINKS Marine Hazards—TRAVELER INFORMATION • Introduction • Risk • Hazards of the Beach • Animals that Bite or Wound • Animals that Envenomate • Animals that are Poisonous to Eat • General Prevention Strategies Traveler Information MARINE HAZARDS INTRODUCTION Coastal waters around the world can be dangerous. Swimming, diving, snorkeling, wading, fishing, and beachcombing can pose hazards for the unwary marine visitor. The seas contain animals and plants that can bite, wound, or deliver venom or toxin with fangs, barbs, spines, or stinging cells. Injuries from stony coral and sea urchins and stings from jellyfish, fire coral, and sea anemones are common. Drowning can be caused by tides, strong currents, or rip tides; shark attacks; envenomation (e.g., box jellyfish, cone snails, blue-ringed octopus); or overconsumption of alcohol. Eating some types of potentially toxic fish and seafood may increase risk for seafood poisoning. RISK Risk depends on the type and location of activity, as well as the time of year, winds, currents, water temperature, and the prevalence of dangerous marine animals nearby. In general, tropical seas (especially the western Pacific Ocean) are more dangerous than temperate seas for the risk of injury and envenomation, which are common among seaside vacationers, snorkelers, swimmers, and scuba divers. Jellyfish stings are most common in warm oceans during the warmer months. The reef and the sandy sea bottom conceal many creatures with poisonous spines. The highly dangerous blue-ringed octopus and cone shells are found in rocky pools along the shore. Sea anemones and sea urchins are widely dispersed. Sea snakes are highly venomous but rarely bite. -

Unit 3 Bites and Stings

First Aid in Common and Environmental Emergencies UNIT 3 BITES AND STINGS Structure 3.0 Introduction 3.1 Objectives 3.2 Bites and Stings 3.2.1 Definition, Causes, Types and Recognition of Bites and Stings 3.2.2 Assessment of the Victim and General First Aid 3.3 Various Bites/Stings 3.3.1 Scorpion Bite and Spider Bite 3.3.2 Snake Bite 3.3.3 Insect Bite 3.3.4 Animal Bites (Dog Bite/Monkey Bites) 3.3.5 Human Bites 3.4 Let Us Sum Up 3.5 Keywords 3.6 Answers to Check Your Progress 3.7 References and Further Readings 3.0 INTRODUCTION Bites and stings are commonly seen in the rural and remote areas. Nowadays, however, they can occur in urban areas also. Lakhs of people every year are bitten or stung by someone or something. These emergencies include bites and stings due to various reasons. These bites or stings need to be identified and treated early as they affect some part or the whole of the body which can cause mild, moderate or severe reaction and can even be life-threatening. Most are not medical emergencies but however, treatment is usually required if there is bleeding, wounds or infection. All bites and stings are not same. Different First Aid treatment and care is needed depending on the type of insect or animal that has caused the bite. Some species are more dangerous and cause more harm compared to others. Hence, in this unit we shall discuss the different types of bites and stings, causes, recognition and first aid in these situations. -

Approach and Management of Spider Bites for the Primary Care Physician

Osteopathic Family Physician (2011) 3, 149-153 Approach and management of spider bites for the primary care physician John Ashurst, DO,a Joe Sexton, MD,a Matt Cook, DOb From the Departments of aEmergency Medicine and bToxicology, Lehigh Valley Health Network, Allentown, PA. KEYWORDS: Summary The class Arachnida of the phylum Arthropoda comprises an estimated 100,000 species Spider bite; worldwide. However, only a handful of these species can cause clinical effects in humans because many Black widow; are unable to penetrate the skin, whereas others only inject prey-specific venom. The bite from a widow Brown recluse spider will produce local symptoms that include muscle spasm and systemic symptoms that resemble acute abdomen. The bite from a brown recluse locally will resemble a target lesion but will develop into an ulcerative, necrotic lesion over time. Spider bites can be prevented by several simple measures including home cleanliness and wearing the proper attire while working outdoors. Although most spider bites cause only local tissue swelling, early species identification coupled with species-specific man- agement may decrease the rate of morbidity associated with bites. © 2011 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. More than 100,000 species of spiders are found world- homes and yards in the southwestern United States, and wide. Persons seeking medical attention as a result of spider related species occur in the temperate climate zones across bites is estimated at 50,000 patients per year.1,2 Although the globe.2,5 The second, Lactrodectus, or the common almost all species of spiders possess some level of venom, widow spider, are found in both temperate and tropical 2 the majority are considered harmless to humans. -

Summary of Reported Animal Bites, 2019 Allegheny County, PA

Summary of Reported Animal Bites, 2019 Allegheny County, PA Prepared by S. Grace Hutko, BS Graduate School of Public Health University of Pittsburgh Kristen Mertz, MD, MPH Infectious Disease Epidemiology Program Allegheny County Health Department L. Renee Miller, BS, BSN, RN Immunization Program Allegheny County Health Department February 2021 Introduction Rabies, a viral zoonotic disease that is nearly always fatal, is a significant global public health concern.1 Worldwide, rabies causes tens of thousands of deaths every year, with dog bites responsible for 99% of human cases.2 In the United States, however, most rabies is found in wild animals, such as bats and raccoons, and there are only one or two human cases per year. In Pennsylvania, there have not been any cases of human rabies since 1984.1 The low incidence of human rabies in the US is attributed to a robust public health surveillance and testing system, widespread availability of post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), and rabies vaccination for pets.3 In Pennsylvania, all healthcare providers are required by law to report animal bites.4 In the event a domestic animal bites a human, the animal is placed on in-home quarantine, usually for a period of ten days, and monitored for signs of rabies. If the animal is already deceased, the owner is asked to submit the animal for testing. If the animal is unavailable for observation or testing, or tests positive for rabies, the victim is directed to seek medical care to receive PEP. PEP includes rabies immune globulin given on day 0 and rabies vaccine given on days 0, 3, 7, and 14 after being evaluated by a healthcare provider. -

A Guide to Harmful and Toxic Creatures in the Goa of Jordan

Published by the Royal Marine Conservation Society of Jordan. P. O. Box 831051, Abdel Aziz El Thaalbi St., Shmesani 11183. Amman Copyright: © The Royal Marine Conservation Society of Jordan Reproduction of this publication for educational and other non- commercial purposes is authorized without prior written approval from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. ISBN: 978-9957-8740-1-8 Deposit Number at the National Library: 2619/6/2016 Citation: Eid, E and Al Tawaha, M. (2016). A Guide to Harmful and Toxic Creature in the Gulf of Aqaba of Jordan. The Royal Marine Conservation Society of Jordan. ISBN: 978-9957-8740-1-8. Pp 84. Material was reviewed by Dr Nidal Al Oran, International Research Center for Water, Environment and Energy\ Al Balqa’ Applied University,and Dr. Omar Attum from Indiana University Southeast at the United State of America. Cover page: Vlad61; Shutterstock Library All photographs used in this publication remain the property of the original copyright holder, and it should not be reproduced or used in other contexts without permission. 1 Content Index of Creatures Described in this Guide ......................................................... 5 Preface ................................................................................................................ 6 Part One: Introduction ......................................................................................... 8 1.1 The Gulf of Aqaba; Jordan ......................................................................... 8 1.2 Aqaba; -

Euteleost Tree of Life – Web Module Summative Evaluation Report

Euteleost Tree of Life – Web Module Summative Evaluation Report Submitted to: University of Kansas Submitted by: July 2013 Julia Hazer Adam Moylan 595 Market Street Suite 2570 • San Francisco, CA 94105-2802 • 415.544.0788 • FAX 415.544.0789 www.rockman.com Table of Contents Introduction.............................................................................................................................................1 Methodology............................................................................................................................................2 Phase 1: Background Survey & Web Module Activities ............................................................................ 2 Phase 2: Focus Group Discussion........................................................................................................................ 5 Participant Background Information .............................................................................................6 Demographics ............................................................................................................................................................. 6 Prior Science Performance and Attitudes....................................................................................................... 6 Prior Evolutionary Tree Knowledge.................................................................................................................. 7 Findings.....................................................................................................................................................9 -

Proceedings of the United States National Museum

NOTE ON THE GENERA OE SYNANCEINE AND PELORINE FISHES. By Theodore Gill, Honorarii Associate in Zoology. For a long time I have been in doubt respecting- the application of the name Synanceia and the consequent nomenclature of some other genera of the same group. Complication has resulted by reason of the intrusion of the incompetent Swainson into the field. In 1801 Bloch and Schneider's name Synanceja was published (p. 194) with a definition, and the only species mentioned were named as follows: 1. HoRRiDA Synanceia horrida. 2. Uranoscopa Tracldcephalus uranoscopus. 3. Verrucosa Synanceia verrucosa. 4. DiDACTYLA Simopias didactylus. 5. RuBicuNDA Simopias didactylus. 6. Papillosus Scorpsena cottoides. Two of the species having been withdrawn from the genus by Cuvier to foi'm the genus Pelor (1817), and one to serve for the genus Trachi- cephalus (1839), the name Synanceja was thus restricted to tlie horrida and verrucosa. In 1839 Swainson attempted to reclassif}^ the Sjmanceines and named three genera, but on each of the three pages of his work (II, pp. 61, 180, 268) in which he treats of those fishes he has expressed difl'erent views. On page 61 the names of Sj^nanchia, Pelor, Erosa, Trichophasia, and Hemitripterus appear as "genera of the Synanchinte" and analogues of five genera of "Scorpaeninte." On page 180 the following names are given under the head of Synanchinae: Agriopus. Synanchia, with three subgenera, viz: Synanchia. Bufichthys. TrachicephahxH. Trichodon. Proceedings U. S. National Museum, Vol. XXVIII— No. 1394. Proc. N. M. vol. xxviii—0-1 15 221 222 PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL MUSEUM. -

Long-Term Effects of Snake Envenoming

toxins Review Long-Term Effects of Snake Envenoming Subodha Waiddyanatha 1,2, Anjana Silva 1,2 , Sisira Siribaddana 1 and Geoffrey K. Isbister 2,3,* 1 Faculty of Medicine and Allied Sciences, Rajarata University of Sri Lanka, Saliyapura 50008, Sri Lanka; [email protected] (S.W.); [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (S.S.) 2 South Asian Clinical Toxicology Research Collaboration, Faculty of Medicine, University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya 20400, Sri Lanka 3 Clinical Toxicology Research Group, University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW 2308, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +612-4921-1211 Received: 14 March 2019; Accepted: 29 March 2019; Published: 31 March 2019 Abstract: Long-term effects of envenoming compromise the quality of life of the survivors of snakebite. We searched MEDLINE (from 1946) and EMBASE (from 1947) until October 2018 for clinical literature on the long-term effects of snake envenoming using different combinations of search terms. We classified conditions that last or appear more than six weeks following envenoming as long term or delayed effects of envenoming. Of 257 records identified, 51 articles describe the long-term effects of snake envenoming and were reviewed. Disability due to amputations, deformities, contracture formation, and chronic ulceration, rarely with malignant change, have resulted from local necrosis due to bites mainly from African and Asian cobras, and Central and South American Pit-vipers. Progression of acute kidney injury into chronic renal failure in Russell’s viper bites has been reported in several studies from India and Sri Lanka. Neuromuscular toxicity does not appear to result in long-term effects. -

Venom Evolution Widespread in Fishes: a Phylogenetic Road Map for the Bioprospecting of Piscine Venoms

Journal of Heredity 2006:97(3):206–217 ª The American Genetic Association. 2006. All rights reserved. doi:10.1093/jhered/esj034 For permissions, please email: [email protected]. Advance Access publication June 1, 2006 Venom Evolution Widespread in Fishes: A Phylogenetic Road Map for the Bioprospecting of Piscine Venoms WILLIAM LEO SMITH AND WARD C. WHEELER From the Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Environmental Biology, Columbia University, 1200 Amsterdam Avenue, New York, NY 10027 (Leo Smith); Division of Vertebrate Zoology (Ichthyology), American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, NY 10024-5192 (Leo Smith); and Division of Invertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, NY 10024-5192 (Wheeler). Address correspondence to W. L. Smith at the address above, or e-mail: [email protected]. Abstract Knowledge of evolutionary relationships or phylogeny allows for effective predictions about the unstudied characteristics of species. These include the presence and biological activity of an organism’s venoms. To date, most venom bioprospecting has focused on snakes, resulting in six stroke and cancer treatment drugs that are nearing U.S. Food and Drug Administration review. Fishes, however, with thousands of venoms, represent an untapped resource of natural products. The first step in- volved in the efficient bioprospecting of these compounds is a phylogeny of venomous fishes. Here, we show the results of such an analysis and provide the first explicit suborder-level phylogeny for spiny-rayed fishes. The results, based on ;1.1 million aligned base pairs, suggest that, in contrast to previous estimates of 200 venomous fishes, .1,200 fishes in 12 clades should be presumed venomous. -

Z:\My Documents\WPDOCS\IACUC

ZOONOTIC DISEASES OF LABORATORY, AGRICULTURAL, AND WILDLIFE ANIMALS July, 2007 Michael S. Rand, DVM, DACLAM University Animal Care University of Arizona PO Box 245092 Tucson, AZ 85724-5092 (520) 626-6705 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.ahsc.arizona.edu/uac Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Amebiasis ............................................................................................................................................... 5 B Virus .................................................................................................................................................... 6 Balantidiasis ........................................................................................................................................ 6 Brucellosis ........................................................................................................................................ 6 Campylobacteriosis ................................................................................................................................ 7 Capnocytophagosis ............................................................................................................................ 8 Cat Scratch Disease ............................................................................................................................... 9 Chlamydiosis .....................................................................................................................................