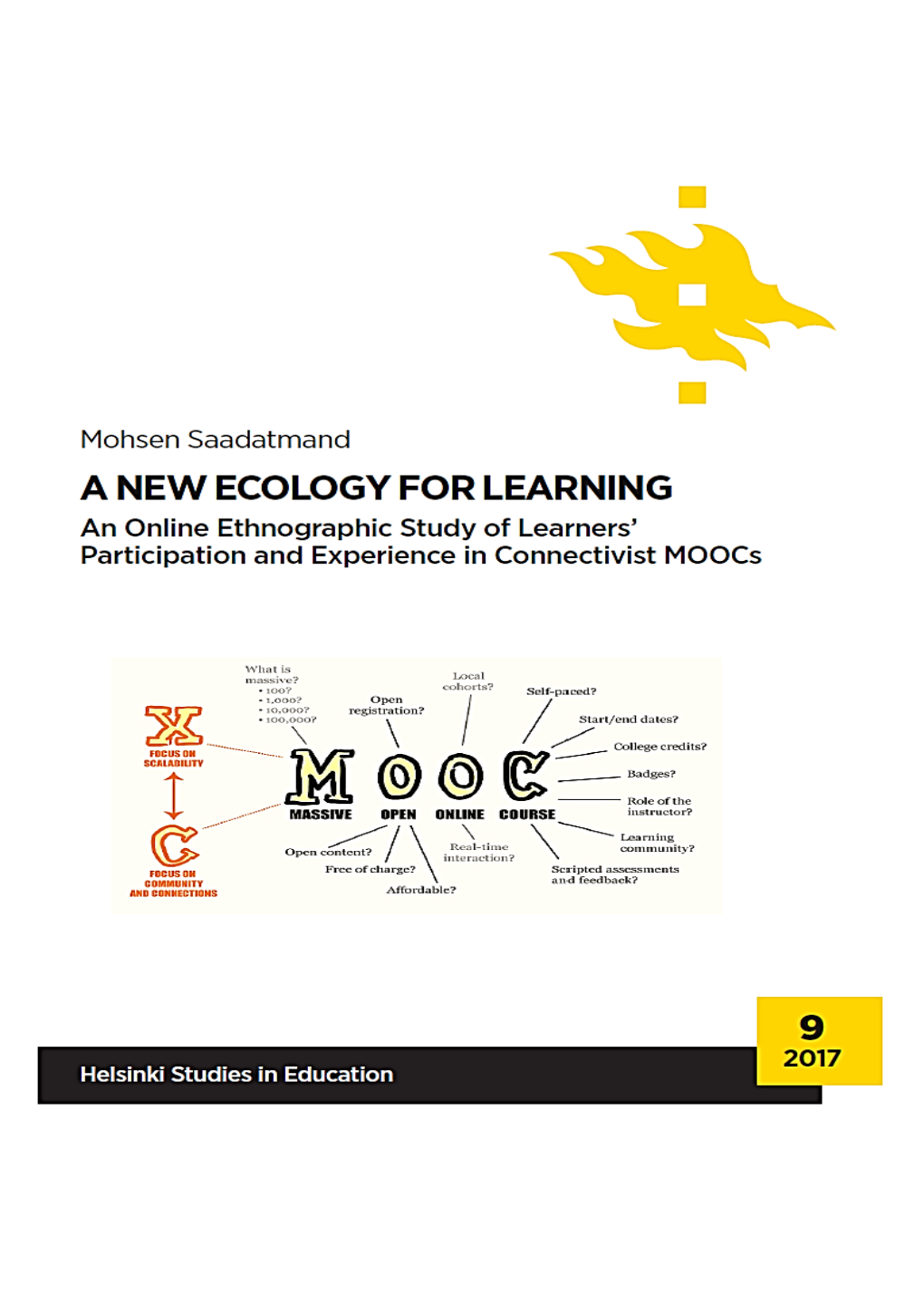

A NEW ECOLOGY for LEARNING : an Online Ethnographic Study Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethnographies of Science Education: Situated Practices of Science Learning for Social/Political Transformation

Ethnographies of science education: situated practices of science learning for social/political transformation By: Carol B. Brandt, Heidi Carlone Brandt, C. & Carlone, H.B. (2012). Ethnographies of science education: Situated practices of science learning for social/political transformation. Ethnography and Education, 7(2), 143-150. This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis Group in Ethnography and Education on 18 Jul 2012, available online at: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/17457823.2012.693690. ***© Taylor & Francis. Reprinted with permission. No further reproduction is authorized without written permission from Taylor & Francis. This version of the document is not the version of record. Figures and/or pictures may be missing from this format of the document. *** Abstract: This article is an introductory essay to the Ethnography and Education special issue Ethnographies of science education: situated practices of science learning for social/political transformation. Keywords: Science Education | Ethnography | Culture Article: Transforming science education has been cited as a global imperative in terms of: producing technological innovation to maintain economic security (Bybee and Fuchs 2006; Tytler 2007); creating critical consumers of scientific knowledge (Osborne and Dillon2008) and fostering a more environmentally sustainable and equitable world (Calabrese Barton 2001; Carter 2008). In light of these agendas, viewing science as a cultural process has significantly contributed to our understanding -

The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences Edited by R

Cambridge University Press 0521845548 - The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences Edited by R. Keith Sawyer Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences Learning sciences is an interdisciplinary field that studies teaching and learning. The sciences of learning include cognitive science, educational psychology, computer sci- ence, anthropology, sociology, neuroscience, and other fields. The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences shows how educators can use the learning sciences to design more effective learning environments, including school classrooms and informal settings such as science centers or after-school clubs, online distance learning, and computer- based tutoring software. The chapters in this handbook describe exciting new classroom environments, based on the latest science about how children learn. CHLS is a true handbook: readers can use it to design the schools of the future – schools that will prepare graduates to participate in a global society that is increasingly based on knowledge and innovation. R. Keith Sawyer is Associate Professor of Education at Washington University in St. Louis. He received his Ph.D. in Psychology at the University of Chicago and his S.B. in Computer Science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He studies cre- ativity, collaboration, and learning. Dr. Sawyer has written or edited eight books. His most recent book is Explaining Creativity: The Science of Human Innovation (2006). © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521845548 - The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences Edited by R. Keith Sawyer Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences Edited by R. Keith Sawyer Washington University © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521845548 - The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences Edited by R. -

The Learning Sciences: the Very Idea Liam Rourkea* and Norm Friesenb Ananyang Technological University, Singapore; Bsimon Fraser University, Canada

Educational Media International, Vol. 43, No. 4, December 2006, pp. 271–284 The learning sciences: the very idea Liam Rourkea* and Norm Friesenb aNanyang Technological University, Singapore; bSimon Fraser University, Canada TaylorREMI_A_192539.sgm10.1080/09523980600926226Educational0952-3987Original2006434000000DecemberLiamRourkeliam.rourke@gmail.com and& Article Francis (print)/1469-5790Francis Media 2006 LtdInternational (online) Attempts to frame the study of teaching and learning in explicitly scientific terms are not new, but they have been growing in prominence. Journals, conferences, and centres of learning science are appearing with remarkable frequency. However, in most of these invocations of an educational science, science itself is understood largely in progressivist, positivistic terms. More recent theory, sociology, and everyday practice of science are ignored in favour of appeals to apparently idealized scientific rigour and efficiency. We begin this article by considering a number of examples of prominent scholarship undermining this idealization. We then argue that learning and education are inescapably interpretive activities that can only be configured rhetorically rather than substantially as science. We conclude by arguing for the relevance of a broader and self-consciously rhetorical/metaphorical conception of science, one that would include the possibility of an interpretive human science. Science et apprentissage: l’idée elle-même Les tentatives visant à enchâsser l’étude de l’enseignement et de l’apprentissage dans des termes explicitement scientifiques, ne sont pas nouvelles mais elles sont de plus en plus marquées. Des revues, des conférences et des centres de science de l’apprentissage apparaissent de plus en plus fréquemment. Dans la plupart de ces invoca- tions à une science éducative le mot science est toutefois pris dans un sens largement positiviste et progressiste. -

A Compendium of Case Studies and Interviews with Experts About Open Education Practices and Resources

A Compendium of Case Studies and Interviews with Experts about Open Education Practices and Resources A Compendium of Case Studies and Interviews with Experts Practices about Open Education 1 To read the full report, please visit: www.openmedproject.eu This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Inter- national License (CC BY 4.0). This means that you are free to: • Share – copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format • Adapt – remix, transform, and build upon the material You may do so for any purpose, even commercially. However, you must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. Please credit this Executive Summary of the report to: Wimpenny, K., Merry, S.K., Tombs, G. & Villar-Onrubia, D. (eds) (2016), Opening Up Education in South Mediterranean Countries: A Compendi- um of Case Studies and Interviews with Experts about Open Education- al Practices and Resources. OpenMed, ISBN 978-1-84600-0 The European Commission support for the production of this publication does not con- stitute an endorsement of the contents which reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. 2 Introduction OpenMed is an international cooperation project co-funded by the Erasmus + Capacity Building in HE programme of the European Union during the period 15 October 2015 - 14 October 2018 involving five partners from Europe and eight from South-Mediterranean (S-M) countries (Morocco, Palestine, Egypt and Jordan). -

Clemson University, Ph.D., Learning Sciences, Program Proposal, CAAL, 8/7/2014 – Page 1 CAAL 8/7/14 Agenda Item 4C

CAAL 8/7/14 Agenda Item 4c New Program Proposal Doctor of Philosophy in Learning Sciences Clemson University Summary Clemson University requests approval to offer a program leading to the Doctor of Philosophy in Learning Sciences to be implemented in January 2015. The proposed program is to be offered through traditional instruction. The following chart outlines the stages for approval of the proposal; the Advisory Committee on Academic Programs (ACAP) voted to recommend approval of the proposal. The full program proposal is attached. Stages of Consideration Date Comments Program Planning Summary 2/11/14 received and posted for comment Program Planning Summary 3/30/14 One ACAP member noted that the research considered by ACAP through methods courses appear strong in this degree, electronic review but also suggested adding coursework in cognitive theory and design. Another ACAP member stated that the proposed program is similar to USC Columbia’s Ph.D. program in Educational Psychology and Research. Program Proposal Received 5/15/14 ACAP Consideration 6/19/14 ACAP members suggested the proposal include statements about how the program differs from Educational Psychology programs. ACAP also recommended the addition of recruitment strategy statements to address USC Columbia’s concerns about competition. ACAP requested a revised budget and budget justification. Comments and suggestions 6/20/14 Staff requested additional information about from CHE staff sent to the potential employment opportunities and institution specificity about what students will be able to do and in which positions they might reasonably expect employment. Staff also requested a new letter of evaluation because the letter provided did not adequately address the proposed courses/curriculum, faculty, or resources required. -

Refining Qualitative Ethnographies Using Epistemic Network Analysis: a Study of Socioemotional Learning Dimensions in a Humanistic Knowledge Building Community

Computers & Education 156 (2020) 103943 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Computers & Education journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/compedu Refining qualitative ethnographies using Epistemic Network Analysis: A study of socioemotional learning dimensions in a Humanistic Knowledge Building Community Yotam Hod a,*, Shir Katz a, Brendan Eagan b a University of Haifa, Israel b University of Wisconsin, Madison, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Contemporary educational research has increasingly pointed to socioemotional dimensions of Cooperative/collaborative learning learning as important in promoting academic progress and sociocognitive developments. Data science applications in education Epistemic Network Analysis, a methodology for producing quantitative ethnographies based on Learning communities complex learning environments, has only begun to examine socioemotional facets of learning in Pedagogical issues classrooms. The aim of this research is to investigate what and how Epistemic Network Analysis Post-secondary education can contribute to qualitative, socioemotionally-focused ethnographies of classroom learning communities. To do this, we employed Epistemic Network Analysis to analyze data collected during a semester of studies, in parallel to a stage developmental analysis of the same community using qualitative methods. The results of this study specifically show the importance of prior experience and how this interacts with participants’ connectedness to the community, as well as how group dynamics are a vital aspect of community discourse and that the socioemotional di mensions that people attach to it may be the determinants of stage advancement. More generally, this study shows how Epistemic Network Analysis can be used to better understand complex socioemotional phenomena in learning communities by combining it with deep, qualitative ethnographies. -

Ethnography of Human Development, Cognition and Learning

EDPSY 582A —Methods Seminar: Ethnography of Human Development, Cognition and Learning Fall 2014 Wednesdays 1:30 to 3:50 Miller 112 INSTRUCTORS Philip Bell Megan Bang LIFE Center LIFE Center [email protected] [email protected] Office Hours: By appt Office Hours: By appt COURSE OVERVIEW “The situated nature of learning, remembering, and understanding is a central fact. It may appear obvious that human minds develop in social situations, and that they use the tools and representational media that culture provides to support, extend, and reorganize mental functioning. But cognitive theories of knowledge representation and educational practice, in school and in the workplace, have not been sufficiently responsive to questions about these relationships.” — Roy Pea & John Seely Brown, 1991 “If ethnography produces cultural interpretations through intense field research experience, how is such unruly experience transformed into an authoritative written account? How, precisely, is a garrulous, overdetermined, cross-cultural encounter, shot through with power relations and personal cross purposes circumscribed as an adequate version of a more-or-less discrete ‘otherworld,’ composed by an individual author?” — James Clifford Learning and development are complex phenomena. The cultural and cognitive processes bound up in learning can be crucially contingent on the history of local community practices, the social and material conditions of specific situations, and they can span across social settings, activity systems, and cultural groupings and deeply relate to the local history. Learning processes and outcomes can play out across short to long time scales from milliseconds to decades. These complexities pose particular conceptual, methodological, and representational challenges. Studies of human development and learning have taken an ethnographic turn over the last twenty years. -

The Study Group

The future of learning: Grounding educational innovation in the learning sciences R. Keith Sawyer University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill To appear as the final chapter in Sawyer, R. K. (Ed.) The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences, Second Edition, to be published in 2014 by Cambridge University Press. The education landscape has changed dramatically since 2006, when the first edition of this handbook was published. In 2006, the following innovations did not yet exist; today, each of them is poised to have a significant impact on education: Tablet computers, like Apple’s iPad and Microsoft’s Surface. In 2012, Apple released iBooks Author, a free textbook authoring app for instructors to develop their own customized textbooks. Although smartphones were well-established among businesspeople in 2006 (then-popular devices included the BlackBerry and Palm Treo), their market penetration has grown dramatically since the 2007 release of the iPhone, especially among school-age children. The App store—Owners of smartphones including Apple’s iPhone, and phones running Google’s Android and Microsoft’s Draft: Please do not cite Copyright © 2013 Keith Sawyer The future of learning Page 2 Windows Phone, can easily download free or very cheap applications, choosing from hundreds of thousands available. Inexpensive e-readers, like the Kindle and the Nook, have sold well, and are connected to online stores that allow books to be downloaded easily and quickly. Furthermore, since 2006, the following Internet-based educational innovations have been widely disseminated, widely used, and widely discussed: Massive open online courses (MOOCs). MOOCs are college courses, delivered on the Internet, that are open to anyone and are designed to support tens of thousands of students. -

2016 Guide-On-Moocs-For-Policy

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Making Sense of MOOCs A Guide for Policy-Makers in Developing Countries Mariana Patru and Venkataraman Balaji Editors Published by the United Nations Educational, Scientic and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France, and Commonwealth of Learning (COL), 4710 Kingsway, Suite 2500, Burnaby, BC V5H 4M2, Canada © UNESCO and Commonwealth of Learning, 2016 ISBN 978-92-3-100157-4 This publication is available in Open Access under the Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-SA 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/igo/). By using the content of this publication, the users accept to be bound by the terms of use of the UNESCO Open Access Repository (http://www.unesco.org/open-access/terms-use-ccbysa-en) and the Co-Publisher Open Access Repository (http://oasis.col.org). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they are not necessarily those of UNESCO or COL and do not commit the Organizations. Editors: Mariana Patru and Venkataraman Balaji Cover design: Aurelia Mazoyer Cover photo: ©shutterstock/Katty2016 Designed and printed by UNESCO Printed in France Foreword by the President and CEO, Commonwealth of Learning COL’s interest in massive open online courses (MOOCs) is rooted in its mission to increase access to quality education and training in an equitable and affordable manner. -

Understanding the Biden Win from an Aesthetic Perspective Pierce Henderson 8

PRESIDENT FOX NEWS SHUTDOWNS MODERNAPRESIDENT FOX NEWS SHUTDOWNS MODERNA ELECTION BELFER CENTER FOR SCIENCE ELECTION& BELFER CENTER FOR SCIENCE & INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS CONGRESS JOSEPH R. INTBIDEERNATIONALN AFFAIRS CONGRESSIn This Issue: JOSEPH R. BIDEN Kennedy 8 | Understanding the Biden Win from TRUTH CONSERVATIVE ZOOM CHINA AMERI TRUTHCAN CONSERVATIVE ZOOMan Aesthetic CHINA Perspective AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE SENATE85 | OF A Clash betweenTHE Classical UNITED Liberalism, STATES ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATESSchool Public Health, and the Constitution SCHOOLS NANCY PELOSI WALL STREET JOUR SCHOOLSNAL NANCY PELOSI 56 |WALL On Race, Womanhood, STREET and Medicine JOURNAL LOCKDOWN JOHNSON & JOHNSON CENTER LOCKDOWNFORReview JOHNSON & JOHNSON CENTER FOR AMERICAN PROGRESS SOCIAL DISTANCING AM FERICANREE PROGRESS SOCIAL DISTANCING FREE MARKETS MIKE PENCE WASHINGTON POST RECESSMAIORKETSN MIKE PENCE WASHINGTON POST RECESSION STIMULUS VOTING MASKS CAPITOL HILL HERIT STAGEIMULUS VOTING MASKS CAPITOL HILL HERITAGE FOUNDATION WUHAN RESTORE THE SOUL OFFO UNDATIONTHE WUHAN RESTORE THE SOUL OF THE COUNTRY NEW YORK TIMES MITCH MCCONNELLCO CNUNTRYN NEW20 YORK TIMES MITCH20 MCCONNELL CNN JOURNALIST IN-PERSON FREEDOM HOUSE J OURNALISTOF IN-PERSON FREEDOM HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VACCINE DIPLOMACY PROGRESREPRESENTATIVESSIVE VACCINE DIPLOMACY PROGRESSIVE ECONOMY JUSTICE RECALL SHORENSTEIN CEN ECONOMYTER 20JUSTICE RECALL SHORENSTEIN21 CENTER INSURRECTION LIBERTY EQUALITY SPACE FORCE INPRSURRECTIONESS LIBERTY EQUALITY SPACE FORCE PRESS CORPS -

Mapping of Shared Economy Platforms

Mapping of Shared Economy Platforms The Mapping of Shared Economy Platforms has been produced with the technical assistance of 1 TABLE OF CONTENT A. Background and Context B. Purpose of the mission C. Methodology D. Preliminary Findings E. Selection of platforms for further analysis F. Analysis of the platforms G. Recommendations H. About Jamaity The Mapping of Shared Economy Platforms has been produced with the technical assistance of 2 A. Background and Context Within the framework of developing the second generation of the Sharing Economy Platform Youth Without Borders (YWB) in coordination with the Innovation for Change MENA Hub, a mapping will be conducted with the objective of analyzing and understanding the existing similar platforms in the MENA region (their work, target, challenges faced, needs, contain and potential growth and development.). The second generation of the Sharing Economy Platform will be developed to create an inclusive and supportive space. Comprised of civil society organizations from the MENA region, this generation will promote the exchange of services and knowledge among the to strengthen their capacities and encourage dynamic fundraising that enables civic activism across the MENA region. By Conducting a comparative analysis of the existing Sharing Economy Platforms in the MENA region and an assessment of potential features to be developed, this mapping will help form the following: a clear understanding on how to build and manage a platform, a deeper idea on how to set the objectives of the platform, the services, the rules and the benefits of the members. B. Purpose of the mission This mission consists in conducting a mapping on the Sharing Economy Platforms exiting in the MENA region. -

EDUC 639: Design of Learning Environments: Theories, Methods, Designs, and Applications

EDUC 639: Design of Learning Environments: Theories, Methods, Designs, and Applications Professor: Dr. Susan Yoon Class Hours: Tuesday 2pm-4pm TA: Dr. Betty Chandy Office: GSE 437 Room: GSE 200 Phone: 215-746-2526 Office Hours: By appointment Email: [email protected] Course Description This course is a survey of the kinds of theories, methods, design considerations, and applications through which educational researchers understand and design environments to improve learning. The course features the most recent trends in learning primarily through educational technologies. It includes perspectives that consider, who is learning, how it is being learned, what design variables are needed to ensure learning takes place in different learning environments, and societal and technological influences on learning. The educational field that most of the course draws on is called the learning sciences. The learning sciences is a relatively new field of research in education that began in the late 80s. It is an interdisciplinary field consisting of researchers who study among other things, cognition, science and math education, language literacy, anthropological and sociological perspectives, computer science, and educational psychology. Learning scientists study learning as it happens in real world contexts and design resources and environments to improve learning in those contexts. This can happen in school, in informal places, and online. Designing resources and environments can include curricula, instructional strategies, digital and computational tools, and professional development programs. Four main learning goals underpin the course content: 1. Understanding learning needs of youth as they interact in society and in school. 2. Investigating the main learning theories and methods influencing the field and how they are instantiated in practice.