Institutionalizing Informality: the Hawkers’ Question in Post-Colonial Calcutta∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

314 Trumbull Was Apparently Ill-Advised Again, Possibly By

314 BOOK REVIEWS Trumbull was apparently ill-advised again, possibly by expatriate administrators, as seen in his claim that, , Finally, the leadership class already existing under ancient custon is being expanded in depth everywhere by the spread of education, and I have found no significant disposition among the conservative oldsters to stifle the progressive young, despite the generation gap that obtrudes in family life. (282) Most observers of Micronesia would agree that one of the saddest aspects of develop- ment and change in the U.S. administered islands is the fact that the traditional leaders were, for the most part, by-passed in both education and political development. Of all the traditional leaders of Micronesia, there are but a few who are reasonably conver- sant in English, which is the language of government. None of the traditional para- mount chiefs holds an elected office of any consequence. Since I seem to be picking at the author, I may as well advise him to avoid giving spurious etymologies of exotic words. The item he cites as ghoose(p. 135) doesn't mean "bribe" or anything else in any of the languages of Fiji. Nor does Guahan by itself mean "we have". It is simply a place name, the Chamorro version of Guam. Possibly the best feature of this book is the anecdotal and personal touches that come from Mr. Trumbull's familiarity with and love for the islands themselves. Like many a Pacific War vet, he feels for the islands in a very special way which comes through in his writing. -

Hawker Policy in Thailand

Legislative Council Secretariat FS12/13-14 FACT SHEET Hawker policy in Thailand 1. Background 1.1 Similar to many other Asian countries, Thailand has a long history of street vending. In Bangkok, the largest city in Thailand, street vending has provided local Thai people with cheap and convenient access to a wide range of goods and a means of making a living. According to a survey conducted by the International Labour Office1, a majority of street vendors surveyed were satisfied with their occupation because of the income earning opportunity and work autonomy.2 In recent years, street vending has also been considered as a way to nurture entrepreneurship, as well as adding to the tourist attractions of Bangkok by bringing vibrancy and vitality to the city. 1.2 In Bangkok, street vending has brought with it urban problems such as obstruction to pedestrian and vehicular traffic. It has also given rise to hygienic problem as many of street vending activities are related to the sale of cooked food along the streets. As such, the local government has designated various locations as street vending areas subject to regulatory controls such as the restrictions on the trading hours of street vendors. This fact sheet makes reference to the Bangkok city for the study of hawker policy in Thailand, covering information on the regulation and management of street vending, different forms of government-run markets, and the emergence of the new-generation street vendors. 1 International Labour Office is the permanent secretariat of the International Labour Organization. 2 See International Labour Office (2006a). -

Durga Pujas of Contemporary Kolkata∗

Modern Asian Studies: page 1 of 39 C Cambridge University Press 2017 doi:10.1017/S0026749X16000913 REVIEW ARTICLE Goddess in the City: Durga pujas of contemporary Kolkata∗ MANAS RAY Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta, India Email: [email protected] Tapati Guha-Thakurta, In the Name of the Goddess: The Durga Pujas of Contemporary Kolkata (Primus Books, Delhi, 2015). The goddess can be recognized by her step. Virgil, The Aeneid,I,405. Introduction Durga puja, or the worship of goddess Durga, is the single most important festival in Bengal’s rich and diverse religious calendar. It is not just that her temples are strewn all over this part of the world. In fact, goddess Kali, with whom she shares a complementary history, is easily more popular in this regard. But as a one-off festivity, Durga puja outstrips anything that happens in Bengali life in terms of pomp, glamour, and popularity. And with huge diasporic populations spread across the world, she is now also a squarely international phenomenon, with her puja being celebrated wherever there are even a score or so of Hindu Bengali families in one place. This is one Bengali festival that has people participating across religions and languages. In that ∗ Acknowledgements: Apart from the two anonymous reviewers who made meticulous suggestions, I would like to thank the following: Sandhya Devesan Nambiar, Richa Gupta, Piya Srinivasan, Kamalika Mukherjee, Ian Hunter, John Frow, Peter Fitzpatrick, Sumanta Banjerjee, Uday Kumar, Regina Ganter, and Sharmila Ray. Thanks are also due to Friso Maecker, director, and Sharmistha Sarkar, programme officer, of the Goethe Institute/Max Mueller Bhavan, Kolkata, for arranging a conversation on the book between Tapati Guha-Thakurta and myself in September 2015. -

Appellate Jurisdiction

Appellate Jurisdiction Daily Supplementary List Of Cases For Hearing On Friday, 9th of July, 2021 CONTENT SL COURT PAGE BENCHES TIME NO. ROOM NO. NO. HON'BLE JUSTICE I. P. MUKERJI 3 On 09-07-2021 1 1 HON'BLE JUSTICE ANIRUDDHA ROY DB - II At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE HARISH TANDON 28 On 09-07-2021 2 4 HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBHASIS DASGUPTA DB-III At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SOUMEN SEN 16 On 09-07-2021 3 57 HON'BLE JUSTICE HIRANMAY BHATTACHARYYA DB - IV At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SOUMEN SEN 17 On 09-07-2021 4 66 HON'BLE JUSTICE SAUGATA BHATTACHARYYA DB-IV At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBRATA TALUKDAR 11 On 09-07-2021 5 68 HON'BLE JUSTICE SAUGATA BHATTACHARYYA DB - V At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE TAPABRATA CHAKRABORTY 30 On 09-07-2021 6 74 HON'BLE JUSTICE SUVRA GHOSH DB-VI At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE ARINDAM SINHA 4 On 09-07-2021 7 80 HON'BLE JUSTICE BISWAJIT BASU DB-VII At 11:00 AM 5 On 09-07-2021 8 HON'BLE JUSTICE ARIJIT BANERJEE 89 SB At 11:00 AM 8 On 09-07-2021 9 HON'BLE JUSTICE DEBANGSU BASAK 94 SB II At 11:00 AM 9 On 09-07-2021 10 HON'BLE JUSTICE SHIVAKANT PRASAD 116 SB - III At 11:00 AM 13 On 09-07-2021 11 HON'BLE JUSTICE RAJASEKHAR MANTHA 124 SB - IV At 11:00 AM 7 On 09-07-2021 12 HON'BLE JUSTICE SABYASACHI BHATTACHARYYA 150 SB - V At 11:00 AM 26 On 09-07-2021 13 HON'BLE JUSTICE SHEKHAR B. -

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY of ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University Ofhong Kong

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY OF ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University ofHong Kong Asia today is one ofthe most dynamic regions ofthe world. The previously predominant image of 'timeless peasants' has given way to the image of fast-paced business people, mass consumerism and high-rise urban conglomerations. Yet much discourse remains entrenched in the polarities of 'East vs. West', 'Tradition vs. Change'. This series hopes to provide a forum for anthropological studies which break with such polarities. It will publish titles dealing with cosmopolitanism, cultural identity, representa tions, arts and performance. The complexities of urban Asia, its elites, its political rituals, and its families will also be explored. Dangerous Blood, Refined Souls Death Rituals among the Chinese in Singapore Tong Chee Kiong Folk Art Potters ofJapan Beyond an Anthropology of Aesthetics Brian Moeran Hong Kong The Anthropology of a Chinese Metropolis Edited by Grant Evans and Maria Tam Anthropology and Colonialism in Asia and Oceania Jan van Bremen and Akitoshi Shimizu Japanese Bosses, Chinese Workers Power and Control in a Hong Kong Megastore WOng Heung wah The Legend ofthe Golden Boat Regulation, Trade and Traders in the Borderlands of Laos, Thailand, China and Burma Andrew walker Cultural Crisis and Social Memory Politics of the Past in the Thai World Edited by Shigeharu Tanabe and Charles R Keyes The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I PRESS HONOLULU Editorial Matter © 2002 David Y. -

BIBLIOGRAPHY Primary Sources: Secondary Sources

BIBLIOGRAPHY Primary Sources: Records and Proceedings, Private and party organizational papers Autobiographies and Memoirs Personal Interviews with some important Political Leaders and Journalists of West Bengal Newspapers and Journals Other Documents Secondary Sources: Books (in English) Article (in English) Books (in Bengali) Article (in Bengali) Novels (in Bengali) 11 BIBLIOGRAPHY Primary Sources Records and Proceedings 1. Bengal Legislative Assembly Proceedings Vol. LII, No.4, 1938. 2. Bengal Legislative Assembly Proceedings, 1939, Vol. LIV, No.2, 3. Bengal Legislative Assembly Proceedings, 1940, vol. LVII, No.5. 4. Bengal Legislative Assembly Proceedings-Vol. LIII, No. 4. 5. Election Commission of India; Report on the First, Second, Third, Fourth, Fifth and Sixth General Election. 6. Fortnightly Report on the Political Situation in Bengal, 2nd half of April, 1947. Govt. of Bengal. 7. Home Department’s Confidential Political Records (West Bengal State Archives), (WBSA). 8. Police Records, Special Branch ‘PM’ and ‘PH’ Series, Calcutta (SB). 9. Public and Judicial Proceedings (L/P & I) (India Office Library and Records), (IOLR). 10. Summary of the Proceedings of the Congress Working Committee’, AICC-1, G-30/1945-46. 11. West Bengal Legislative Assembly Proceedings 1950-1972, 1974-1982. Private and party organizational papers 1. All India Congress committee Papers (Nehru Memorial Museum and Library), (NMML). 2. All Indian Hindu Mahasabha Papers (NMML) 3. Bengal Provislal Hindu Mahasabha Papers (NMML). 4. Kirn Sankar Roy Papers (Private collection of Sri Surjya Sankar Roy, Calcutta) 414 5. Ministry of Home Affairs Papers (National Achieves of India), (NAI). 6. Syama Prasad Mookerjee Papers (NMML). Autobiographies and Memoirs 1. Basu Hemanta Kumar, Bhasan O Rachana Sangrahra (A Collection of Speeches and Writings), Hemanta Kumar Basu Janma Satabarsha Utjapan Committee, Kolkata, 1994. -

Hawkers' Movement in Kolkata, 1975-2007

NOTES hawkers’ cause. More than 32 street-based Hawkers’ Movement hawker unions, with an affiliation to the mainstream political parties other than the in Kolkata, 1975-2007 ruling Communist Party of India (Marxist), better known as CPI(M), constitute the body of the HSC. The CPI(M)’s labour wing, Centre Ritajyoti Bandyopadhyay of Indian Trade Unions (CITU), has a hawk- er branch called “Calcutta Street Hawkers’ In Kolkata, pavement hawking is n recent years, the issue of hawkers Union” that remains outside the HSC. The an everyday phenomenon and (street vendors) occupying public space present paper seeks to document the hawk- hawkers represent one of the Iof the pavements, which should “right- ers’ movement in Kolkata and also the evo- fully” belong to pedestrians alone, has lution of the mechanics of management of largest, more organised and more invited much controversy. The practice the pavement hawking on a political ter- militant sectors in the informal of hawking attracts critical scholarship rain in the city in the last three decades, economy. This note documents because it stands at the intersection of with special reference to the activities of the hawkers’ movement in the city several big questions concerning urban the HSC. The paper is based on the author’s governance, government co-option and archival and field research on this subject. and reflects on the everyday forms of resistance (Cross 1998), property nature of governance. and law (Chatterjee 2004), rights and the Operation Hawker, 1975 very notion of public space (Bandyopadhyay In 1975, the representatives of Calcutta 2007), mass political activism in the context M unicipal Corporation (henceforth corpora- of electoral democracy (Chatterjee 2004), tion), Calcutta Metropolitan Development survival strategies of the urban poor in the Authority (CMDA), and the public works context of neoliberal reforms (Bayat 2000), d epartment (PWD) jointly took a “decision” and so forth. -

Ritajyoti Bandyopadhyay: Archiving from Below

Archiving from Below: The Case of the Mobilised Hawkers in Calcutta by Ritajyoti Bandyopadhyay University of California, Berkeley and Jadavpur University Sociological Research Online 14(5)7 <http://www.socresonline.org.uk/14/5/7.html> doi:10.5153/sro.2008 Received: 17 Mar 2009 Accepted: 4 Oct 2009 Published: 30 Nov 2009 Abstract In the last two decades or more, critical scholarship in the human sciences has been commenting on different aspects of the 'archive'. While much has been said on the archive of the state, especially in the historiography of colonial South Asia, very little is known about the archival functions of political parties, movements, grassroots community organisations, and trade unions that are involved in the governance of populations in the post-colonial state. The paper argues that archival claims lie at the heart of negotiations between the state and population groups. It looks at the archival function of the Hawker Sangram Committee (HSC) in Calcutta to substantiate the point. Following Operation Sunshine (1996), a move by the state to forcibly evict hawkers from some selected pavements of Calcutta, in order to reclaim such 'public' spaces, a mode of collective resistance developed under the banner of the HSC. The HSC has subsequently come to occupy a central position in the governance of the realm of pavement-hawking through the creation and maintenance of an archival database that articulates the entrepreneurial capacity of the 'poor hawker' and his ability to deliver goods and services at low-cost. The significance of the HSC's archive is that, it enables the organisation to form a moral and rational critique of the exclusionary discourses on the hawker, mostly propagated by a powerful combination of a few citizens' associations, the judiciary and the press. -

CCIM-11B.Pdf

Sl No REGISTRATION NOS. NAME FATHER / HUSBAND'S NAME & DATE 1 06726 Dr. Netai Chandra Sen Late Dharanindra Nath Sen Dated -06/01/1962 2 07544 Dr. Chitta Ranjan Roy Late Sahadeb Roy Dated - 01-06-1962 3 07549 Dr. Amarendra Nath Pal late Panchanan Pal Dated - 01-06-1962 4 07881 Dr. Suraksha Kohli Shri Krishan Gopal Kohli Dated - 30 /05/1962 5 08366 Satyanarayan Sharma Late Gajanand Sharma Dated - 06-09-1964 6 08448 Abdul Jabbar Mondal Late Md. Osman Goni Mondal Dated - 16-09-1964 7 08575 Dr. Sudhir Chandra Khila Late Bhuson Chandra Khila Dated - 30-11-1964 8 08577 Dr. Gopal Chandra Sen Gupta Late Probodh Chandra Sen Gupta Dated - 12-01-1965 9 08584 Dr. Subir Kishore Gupta Late Upendra Kishore Gupta Dated - 25-02-1965 10 08591 Dr. Hemanta Kumar Bera Late Suren Bera Dated - 12-03-1965 11 08768 Monoj Kumar Panda Late Harish Chandra Panda Dated - 10/08/1965 12 08775 Jiban Krishna Bora Late Sukhamoya Bora Dated - 18-08-1965 13 08910 Dr. Surendra Nath Sahoo Late Parameswer Sahoo Dated - 05-07-1966 14 08926 Dr. Pijush Kanti Ray Late Subal Chandra Ray Dated - 15-07-1966 15 09111 Dr. Pratip Kumar Debnath Late Kaviraj Labanya Gopal Dated - 27/12/1966 Debnath 16 09432 Nani Gopal Mazumder Late Ramnath Mazumder Dated - 29-09-1967 17 09612 Sreekanta Charan Bhunia Late Atul Chandra Bhunia Dated - 16/11/1967 18 09708 Monoranjan Chakraborty Late Satish Chakraborty Dated - 16-12-1967 19 09936 Dr. Tulsi Charan Sengupta Phani Bhusan Sengupta Dated - 23-12-1968 20 09960 Dr. -

Public Health Research Series

UNIVERSITY Public Health Research Series 2012 Vol.1, Issue 1 School of Public Health I Preface “A scientist writes not because he wants to say something, but because he has something to say” – F. Scott Fitzgerald The above quote more or less summarizes the essence of this publication. The School of Public Health, SRM University takes great pride and honor in bringing out the first of its Public Health Research Series, a compilation of research papers by the bright and intelligent students of the school. The Series has come out to provide a platfrom for sharing of research work by students and faculty in the field of publuc health. The studies reported in this Series are small pilot projects with scope for scaling up in larger scale to address important public health issues in India. They come from diverse settings spanning the length and breadth of the country, neighboring countries like Nepal and Bhutan, diverse linguistic, cultural and socio economic backgrounds. Some of the projects have generated important hypothesis for further testing, some have done qualitative exploration of interesting concepts and yet others have tried to quantify certain constructs in public health. This book is organized into a set of 25 full reports and 5 briefs. The full reports give an elaborate description of the study objectives, methods and findings with interpretations and discussions of the authors. The briefs are unstructured concept abstracts. The studies were done by the students of the school of public health as their term project under the guidance of the faculty mentors to whom they were assigned at the time of enrolment into the course. -

I: Introduction

I: INTRODUCTION The West Bengal state assembly elections were conducted in five phases. Polling for the Phase-I, II, III, IV and phase-V was held on the 17, 22, and 27 April, 3 and 8 May, 2006 respectively for 294 assembly constituencies. A post-poll survey conducted in 44 out of 294 assembly constituencies. The objective of the survey was to reflect the nature of voting behaviour and attitudes of people on electoral politics in the state. The survey was an attempt to understand the people’s perception on the performance of state government as well as the government at the Centre. Another aim of the CSDS is to generate data bank of surveys held over the years in different parts of the country which helps to make interstate comparison on disposition of the electorates opinion towards different political parties, socio-economic, political, development, and governance issues and to understand electorates’ behavior pattern which varies with region, community, religion, class, and gender. Table -1: Background of the Assembly election in West Bengal , 2006 Total Number of Assembly Constituencies(AC) 294 Number of seats for General Category 218 Number of seats reserved for Scheduled Caste 59 Number of seats reserved for Scheduled Tribe 17 Total Number of Voters 48165201 Voter turn out (%) 82 Source: Indian election statistics are available at the Election Commission of India’s website: www.eci.gov.in. Table-2: Election Results Party Seats Contested Seats won Votes Share (percent) 294 235 50 Left Front (Alliance) 13 8 2 • CPI 212 176 37 • CPM 23 20 4 • RSP 34 23 6 • FBL 4 4 1 • WBSP 12 8 1 • Other * INC**(Alliance) 292 21 15 NDA (Alliance) 294 31 29 • TRMC 257 30 27 • NDAIND 8 1 0.4 • Others*** 159 0 2.7 Independent**** 656 5 4 SourceIndian election statistics are available at the Election Commission of India’s website: www.eci.gov.in. -

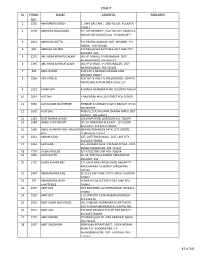

Sl Form No. Name Address Remarks

STARLIT SL FORM NAME ADDRESS REMARKS NO. 1 2235 ABHIMANYU SINGH 2, UMA DAS LANE , 2ND FLOOR , KOLKATA- 700013 2 1998 ABHISHEK MAJUMDER R.P. APPARTMENT , FLAT NO-303 PRAFULLA KANAN (W) KOLKATA-101 P.S-BAGUIATI 3 1922 ABHRANIL DUTTA P.O-PRAFULLANAGAR DIST-24PGS(N) , P.S- HABRA , PIN-743268 4 860 ABINASH HALDER 139 BELGACHIA EAST HB-6 SALT LAKE CITY KOLKATA -106 5 2271 ABU HENA MONIRUL ALAM VILL+P.O-MILKI, P.S-REJINAGAR DIST- MURSHIDABAD, PIN-742163 6 1395 ABU HENA SAHINUR ALAM VILL+P.O-MILKI , P.S-REGINAGAR , DIST- MURSHIDABAD, PIN-742163 7 446 ABUL HASAN B 32 1AH 3 MIAJAN OSTAGAR LANE KOLKATA 700017 8 3286 ADA AFREEN FLAT NO 9I PINES IV GREENWOOD SONATA NEWTOWN ACTION AREA II KOL 157 9 1623 ADHIR GIRI 8 DURGA CHANDRA ROAD KOLKATA 700014 10 2807 AJIT DAS 6 RAJENDRA MULLICK STREET KOL-700007 11 3650 AJIT KUMAR MUKHERJEE SHIBBARI K,S ROAD P.O &P.S NAIHATI DT 24 PGS NORTH 12 1602 AJOY DAS PO&VILL SOUTH GARIA CHARAK MATH DIST 24 PGS S PIN 743613 13 1261 AJOY KUMAR GHOSH 326 JAWPUR RD. DUMDUM KOL-700074 14 1584 AKASH CHOUDHURY DD-19, NARAYANTALA EAST , 1ST FLOOR BAGUIATI , KOLKATA-700059 15 2460 AKHIL CHANDRA ROY MNJUSRI 68 RANI RASHMONI PATH CITY CENTRE ROY DURGAPUR 713216 16 2311 AKRAM AZAD 227, DUTTABAD ROAD, SALT LAKE CITY , KOLKATA-700064 17 1441 ALIP JANA VILL-KHAMAR CHAK P.O-NILKUNTHIA , DIST- PURBA MIDNAPORE PIN-721627 18 2797 ALISHA BEGUM 5/2 B DOCTOR LANE KOL-700014 19 1956 ALOK DUTTA AC-64, PRAFULLA KANAN KRISHNAPUR KOLKATA -101 20 1719 ALOKE KUMAR DEY 271 SASHI BABU ROAD SAHID NAGAR PO KANCHAPARA PS BIZPUR 24PGSN PIN 743145 21 3447