The Living Structures of Ken Isaacs June 21–October 5, 2014 Fig

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2016 Newsletter

Fall 2016 CHI College Dean’s welcome CHI Theatre & Music 2016/17 theatre season LA Art & Art History Marientina Gotsis and the art of solving problems CHI, DXB, Architecture JED Adrian SmithCHI comes to Projecting the Forum CHI College Projecting the future: a UIC legacy the future: a DET Design Industrial Design at IDSA conference UIC legacy LIS, VCE Architecture City views: School of Architecture represented in Lisbon and Venice CHI College In memoriam CHI Architecture Legos Brick by Brick at the Museum of Science and Industry DET Industrial CHI Design High in the Modern Wing: Amir Berbic’s installation at the Art Institute of Chicago Design at IDSA CHI College Alumni step out at Steppenwolf NYC Design conference The future, now ACC Art & Art History Congratulations, Daniel Dunson CHI College Sides to our story: east side/ west side collaborationsLIS School of University of Illinois at Chicago College of Architecture, Design, and the Arts Architecture to Lisbon and Venice CHI East side/ west side collaborations Dean’s UIC College of Architecture, Design, and the Arts 2 Fall 2016 has arrived at the University of an arts center for UIC and the city of Geissler, Beate, Oliver Sann, and Brian Illinois at Chicago College of Architecture, Chicago. You can also read descriptions and Recent faculty publications Holmes. Volatile Smile. Nuremberg: Moderne welcomeDesign, and the Arts (CADA), and the see images of luminous design concepts Kunst Nurnberg, 2014. learning environment here is as vibrant as for a new visual and performing arts facility The faculty of UIC's College of Harmansah, Omur. -

Green Good Design 2009

G O O D D E S I G N GREEN GOOD DESIGN 2009 AWARDS FOR THE WORLD'S LEADING SUSTAINABLE DESIGNS THE CHICAGO ATHENAEUM: MUSEUM OF ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN THE EUROPEAN CENTRE FOR ARCHITECTURE ART DESIGN AND URBAN STUDIES PRODUCTS/INDUSTRIAL DESIGN 2009 Bosch Evolution Dishwasher (108) Designers: Marken Design Bosch, Robert Bosch Electrogeräte GmbH., Munich, Germany Manufacturer: BSH Home Appliances Corporation, New Bern, North Carolina, USA Bosch Integra® Refrigeration Dishwasher (109) Designers: Marken Design Bosch, Robert Bosch Electrogeräte GmbH., Munich, Germany Manufacturer: BSH Home Appliances Corporation, New Bern, North Carolina, USA Bosch Nexxt Laundry (110) Designers: Marken Design Bosch, Robert Bosch Electrogeräte GmbH., Munich, Germany Manufacturer: BSH Home Appliances Corporation, New Bern, North Carolina, USA Hansgrohe Electronic Bath Faucets, 2007 (100) Designers: GROHE Design Team, Grohe AG., Düsseldorf, Germany Manufacturer: Grohe AG., Düsseldorf, Germany Full Contact™ Microwaveable Freeze Containers (114) Designers: Jan-Hendrik De Groote and Dimitri Backaert, Tupperware General Services N.V., Aalst, Belgium Manufacturer: Tupperware France S.A., Jove-Les-Tours, France ASKO Line Series Washing Machine (118) Designers: Tobias Stralman, ASKO Appliances, Jung, Sweden and Propeller, Stockholm, Sweden Manufacturer: ASKO Cylinda AB., Vara, Sweden Linoleum xf (122) Designers: Johnsonite/Tarkett, Narni Scalo (TR), Italy Manufacturer: Johnsonite/Tarkett, Narni Scalo (TR), Italy Kast™ LED Task Light (124) Designers: Tom Newhouse, Thomas -

Oral History Interview with Niels Diffrient, 2010 July 28-August 31

Oral history interview with Niels Diffrient, 2010 July 28-August 31 Funding for this interview was provided by the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Niels Diffrient on July 28 and August 30, 2010. The interview took place in Ridgefield, Connecticut, and was conducted by Matilda McQuaid for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This interview is part of the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Niels Diffrient has reviewed the transcript and has made corrections and emendations. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview MATILDA MCQUAID: So this is Matilda McQuaid. I'm interviewing Niels Diffrient at the artist's home and studio in Ridgefield, Connecticut, on July 28 [2010]. And this is for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. And this is card number one. So Niels, I wanted to just see if you could just establish or sort of begin talking about your childhood, where you were born, when you were born. And what specific things in your childhood helped you to get to where you are now — if there was anything or if it happened later. But let's just start at the very beginning. NIELS DIFFRIENT: Well, I was born in Mississippi in 1928, a year before the Great Depression, a small town called Star and the population was, at the time I was born, something like 264. -

Thomas Lamb's “Wedge-Lock”

DESIGN TO ENABLE THE BODY: THOMAS LAMB’S “WEDGE-LOCK” HANDLE, 1941-1962 by Rachel Elizabeth Delphia A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Early American Culture Spring 2005 © 2005 Rachel Elizabeth Delphia All Rights Reserved Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 1426014 Copyright 2005 by Delphia, Rachel Elizabeth All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 1426014 Copyright 2005 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. DESIGN TO ENABLE THE BODY: THOMAS LAMB’S “WEDGE-LOCK” HANDLE, 1941-1962 by Rachel Elizabeth Delphia Approved: J. Rfitchie Garrison, Ph.D. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee a ^ 4 Approved: X —-_____2k J. Ritchie Garrison, Ph.D. Director of the Winterthur Program in Early American Culture Approved: Conrado M. -

50 Notable IDSA Members

QUARTERLY OF THE INDUSTRIAL DESIGNERS SOCIETY OF AMERICA WINTER 2015 50/35/50 50 NOTABLE MEMBERS 35 YEARS OF DESIGN EXCELLENCE 50 MEMORABLE MOMENTS QUARTERLY OF THE INDUSTRIAL DESIGNERS SOCIETY OF AMERICA WINTER 2015 ® Publisher Executive Editor Sr. Creative Director Advertising Annual Subscriptions IDSA Mark Dziersk, FIDSA Karen Berube Katrina Kona Within the US $85 555 Grove St., Suite 200 Managing Director IDSA IDSA Canada & Mexico $100 Herndon, VA 20170 LUNAR | Chicago 703.707.6000 x102 703.707.6000 x100 International $150 P: 703.707.6000 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] F: 703.787.8501 Single Copies www.innovationjournal.org Advisory Council Contributing Editor Subscriptions/Copies Fall/Yearbook $50+ S&H www.idsa.org Gregg Davis, IDSA Jennifer Evans Yankopolus IDSA All others $25+ S&H Alistair Hamilton, IDSA [email protected] 703.707.6000 678.612.7463 [email protected] ® The quarterly publication of the Industrial Designers Society of America (IDSA), INNOVATION provides in-depth cover- age of design issues and long-term trends while communicating the value of design to business and society at large. 50/35/50 14 In Memory IN EVERY ISSUE IDSA AMBASSADORS Carroll Gantz, FIDSA 4 From the Editor 3M, St. Paul, MN By Bret Smith, IDSA, and By Mark Dziersk, FIDSA Banner & Witcoff, Chicago; Washington, DC; Vicki Matranga, H/IDSA 15 What a Difference 50 Years 6 Design Defined Boston; Portland, OR Makes! By Byron Bloch, IDSA Cesaroni Design Associates Inc., Glenview, IL; By Carroll Gantz, FIDSA 8 Beautility Santa Barbara, -

Productbook Ipad 1011.Pdf

WELCOME TO HUMANSCALE Contents • What We Stand For • The Result • Meet Niels Diffrient • The Humanscale Design Studio • Our Design Philosophy • Our Environmental Stance • Our Products WHAT WE STAND FOR Superior Performance Effortless Operation Excellent Quality THE RESULT A more comfortable place to work Named a design “Tastemaker” by Forbes.com, Diffrient has amassed an impressive roster of honors, including a 2005 Legend Award from Contract magazine, the 2002 National Design Award from the Smithsonian’s Cooper- Hewitt, National Design Museum, the 1999 Chrysler Award for Innovation, and a 1987 Honorary Royal Designer for Industry designation from England. MEET NIELS DIFFRIENT A Beautiful Relationship The renowned designer Niels Diffrient has worked with Humanscale for 12 years. As an engineer, artist and pioneer in the fi eld of ergonomics, his approach meshes perfectly with our design philosophy. Like us, Diffrient is passionate about performance, comfort and ease of use. He begins by questioning every aspect of conventional design. Why do things look the way they look? Why do they operate the way they operate? How can functionality and performance be elevated without adding cumbersome controls? From his early days working with Eero Saarinen, Marco Zanuso and Henry Dreyfuss, he has insisted that form follow function. What sets Diffrient apart is his ability to achieve timeless beauty, exceptional performance and unparalleled comfort through remarkably simple designs. Among his numerous design innovations are three of the most comfortable chairs imaginable—the Freedom, Liberty and Diffrient World chairs for Humanscale. THE HUMANSCALE DESIGN STUDIO Simply Passionate Humanscale starts with people. Talented people. Accomplished designers who bring exceptional thinking to every challenge. -

1336998933 47.Pdf

WELCOME TO HUMANSCALE Contents • What We Stand For • The Result • Meet Niels Diffrient • The Humanscale Design Studio • Our Design Philosophy • Our Environmental Stance • Our Products WHAT WE STAND FOR Superior Performance Effortless Operation Excellent Quality THE RESULT A more comfortable place to work Named a design “Tastemaker” by Forbes.com, Diffrient has amassed an impressive roster of honors, including a 2005 Legend Award from Contract magazine, the 2002 National Design Award from the Smithsonian’s Cooper- Hewitt, National Design Museum, the 1999 Chrysler Award for Innovation, and a 1987 Honorary Royal Designer for Industry designation from England. MEET NIELS DIFFRIENT A Beautiful Relationship The renowned designer Niels Diffrient has worked with Humanscale for 12 years. As an engineer, artist and pioneer in the field of ergonomics, his approach meshes perfectly with our design philosophy. Like us, Diffrient is passionate about performance, comfort and ease of use. He begins by questioning every aspect of conventional design. Why do things look the way they look? Why do they operate the way they operate? How can functionality and performance be elevated without adding cumbersome controls? From his early days working with Eero Saarinen, Marco Zanuso and Henry Dreyfuss, he has insisted that form follow function. What sets Diffrient apart is his ability to achieve timeless beauty, exceptional performance and unparalleled comfort through remarkably simple designs. Among his numerous design innovations are three of the most comfortable chairs imaginable—the Freedom, Liberty and Diffrient World chairs for Humanscale. THE HUMANSCALE DESIGN STUDIO Simply Passionate Humanscale starts with people. Talented people. Accomplished designers who bring exceptional thinking to every challenge. -

NEA-Annual-Report-1974.Pdf

For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $2.60 National Endowment for the Arts National Council on the Arts Annual Report Fiscal Year 1974 Washington, D.C. To the Cq.ngress oftheUnite~ States am pleased to transmit to the In September 1974, the National Congress the Annual Report Council on the Arts celebrated its I of the National Council on the Tenth Anniversary, and I had the op Arts and the National Endow portunity to congratulate the Council ment for the Arts for the Fiscal and this relatively new Federal agency Year 1974. on its success in creating interest in the Arts throughout the Nation. Our Nation has a diverse and ex tremely rich cultural heritage. It is I believethat theworkoftheNational source of pride and strength to mil Counciland the NationalEndowment lions of Americans who look to the for the Arts has been a great addition arts for inspiration, communication to our society in the United States and and the opportunity for creative we can be very proud of it. self- expression. With the bicentennial of our Nation This Annual Report reflects the role approaching soon, we shall need the of the government in preserving this creative gifts of our artists and the cultural legacy and encouraging fresh capabilities ofour cultural institutions activity, in developing our cultural re- to help us celebrate this great anniver sources and making new connections sary. between the arts and our people. It is my hope that every member of Congress will share my conviction that the arts are ah important and integral part of our society. -

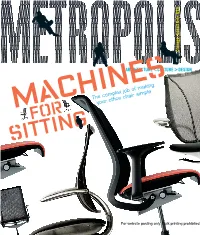

DESIGN the Complex Job of Making Your Office Chair Simple

Green City, USA Green City, Green City, USA Green City, : : METROPOLIS Chicago Chicago ARCHITECTURE <CULTURE >DESIGN July 2004 The complex job of making Machinesyour office chair simple for Sitting For website posting only. Bulk printing prohibited. Features July 2004 Continuing his life-long quest toward an impossible goal—ergonomic perfection—Niels Diffrient is designing a second task chair for Humanscale, a company named after the booklets he co-wrote in the 1970s, a guide to designing for the human body that quickly became the industry standard. Photography by Walter Smith for Metropolis METROPOLIS July 2004 3 Function’s Zen Master Photography by Walter Smith for Metropolis Niels Diffrient’s 50-year quest for ergonomic perfection is, by his own admission, an impossible task, but that hasn’t stopped him from trying. 4 METROPOLIS July 2004 By Peter Hall Up in the barnlike studio he built for him- self and his wife on the site of a former farm in Connecticut, Niels Diffrient is demonstrat- ing one of his inventions. For his wife, tapes- try weaver Helena Hernmarck, he has designed a rather peculiar-looking fan, which is suspended by thin low-voltage wires below the 30-foot-high ceiling. At the flick of a switch, a propeller containing the fan motor whirs around in circles, pulling a larger wing blade and moving the air around with quiet effectiveness. Diffrient figured out he could avoid installing a large central ceiling motor by having the motor fly in circles under its own momentum. “It was a simple way to move it,” he says. -

Design Since 1945 This Book Has Received Significant Support from The

Design Since1945 PHILADELPHIA MUSEUM ART i Design Since 1945 This book has received significant support from the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts. Major funding has also been provided by COLLAB: The Contemporary Design Group for the Philadelphia Museum of Art; The Pew Memorial Trust; and the Design Arts Program of the National Endowment for the Arts, a Federal agency. Design Since 1945 Organized by Jack Lenor Larsen Kathryn B. Hiesinger Olivier Mourgue George Nelson Editors Carl Pott Kathryn B. Hiesinger Jens Quistgaard George H. Marcus Dieter Rams Paul Reilly Contributing Authors Philip Rosenthal Max Bill Timo Sarpaneva Achille Castiglioni Ettore Sottsass, Jr. Bruno Danese Hans J. Wegner Niels Diffrient Marco Zanuso Herbert J. Gans Philadelphia Museum of Art 1983 This book accompanies the exhibition "Design Since 1945" at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, October 16, 1983, through January 8, 1984. The exhibition has been supported by generous grants from Best Products Company, Inc., The Pew Memorial Trust, and the National Endowment for the Humanities, a Federal agency. ERRATA 10: p 228 Dieter Rams biography, line delete "(1-37)." second sentence p. 235 Remhold Weiss biography, should read mixer Mi40 (1-37) are His award-winning table fan (1-50) and hand advo- considered models of the austere design and scientific method themselves to cated by both Ulm and Braun, products that lent of interre- systematic mathematical analysis, ordered assemblages lated component parts, p 246 Index, should read. Rams, Dieter 1-34-36, 111-72 Weiss, Remhold 1-37, 50 c Copyright 1983 by the Composition by Folio Typographers, Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Philadelphia Museum of Art All Pennsauken, N.J.