What Is Essential in the Christian Religion? Is Protestantism a Positive Principle? by Ted Peters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concordia Theological Quarterly

Concordia Theological Quarterly Volume 76:3-4 July/October 2012 Table of Contents Justification: Jesus vs. Paul David P. Scaer ..................................................................................... 195 The Doctrine of Justification in the 19th Century: A Look at Schleiermacher's Der christliche Glaube Naomichi Masaki ................................................................................ 213 Evangelicals and Lutherans on Justification: Similarities and Differences Scott R. Murray ................................................................................... 231 The Finnish School of Luther Interpretation: Responses and Trajectories Gordon L. Isaac ................................................................................... 251 Gerhard Forde's Theology of Atonement and Justification: A Confessional Lutheran Response Jack Kilcrease ....................................................................................... 269 The Ministry in the Early Church Joel C. Elowsky ................................................................................... 295 Walther and AC V Roland Ziegler ..................................................................................... 313 Research Notes ................................................................................................. 335 The Gospel of Jesus' Wife: A Modem Forgery? Theological Observer ...................................................................................... 338 Notes on the NIV The Digital 17th Century Preparing the First -

Defending Faith

Spätmittelalter, Humanismus, Reformation Studies in the Late Middle Ages, Humanism and the Reformation herausgegeben von Volker Leppin (Tübingen) in Verbindung mit Amy Nelson Burnett (Lincoln, NE), Berndt Hamm (Erlangen) Johannes Helmrath (Berlin), Matthias Pohlig (Münster) Eva Schlotheuber (Düsseldorf) 65 Timothy J. Wengert Defending Faith Lutheran Responses to Andreas Osiander’s Doctrine of Justification, 1551– 1559 Mohr Siebeck Timothy J. Wengert, born 1950; studied at the University of Michigan (Ann Arbor), Luther Seminary (St. Paul, MN), Duke University; 1984 received Ph. D. in Religion; since 1989 professor of Church History at The Lutheran Theological Seminary at Philadelphia. ISBN 978-3-16-151798-3 ISSN 1865-2840 (Spätmittelalter, Humanismus, Reformation) Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2012 by Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen, Germany. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher’s written permission. This applies particularly to reproduc- tions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was typeset by Martin Fischer in Tübingen using Minion typeface, printed by Gulde- Druck in Tübingen on non-aging paper and bound Buchbinderei Spinner in Ottersweier. Printed in Germany. Acknowledgements Thanks is due especially to Bernd Hamm for accepting this manuscript into the series, “Spätmittelalter, Humanismus und Reformation.” A special debt of grati- tude is also owed to Robert Kolb, my dear friend and colleague, whose advice and corrections to the manuscript have made every aspect of it better and also to my doctoral student and Flacius expert, Luka Ilic, for help in tracking down every last publication by Matthias Flacius. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Leaming 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMI' PHILIP MELANCHTHON, THE FORMULA OF CONCORD, AND THE THIRD USE OF THE LAW DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ken Ray Schurb, B.A., B.S.Ed., M.Div., M.A., S.T.M. -

1 the Study of Luther in Finland Risto Saarinen the Lutheran

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto 1 The Study of Luther in Finland Risto Saarinen The Lutheran Reformation in Finland established the need for Finnish language in the teachings of the church. This need did not, however, lead to any extensive translations of Luther’s writings. Before the year 1800, only the Catechisms, some hymns and prefaces of Luther’s Bible translation had been translated into Finnish. Until the latter part of the 19th century, Latin and Swedish remained the languages of the Finnish university. The pastors received their education in Latin and Swedish; German books were also frequently read. The Finnish University and National Awakening The Finnish university was founded in Turku in 1640. Lutheran orthodoxy flourished especially during the professorship of Enevaldus Svenonius from 1664 to 1688. In the theological dissertations drafted by him, Luther is the most frequently mentioned person (252 times), followed by Beza (161), Augustine (142) and Calvin (114). Calvin and his companion Beza are, however, almost invariably criticized. Finnish Lutheranism has inherited its later critical attitude towards Calvinism from the period of orthodoxy. Svenonius did not practise any real study of Luther, but he quoted the reformer mostly through using common Lutheran textbooks and, sometimes, Luther’s Commentary on Galatians. Among the very few dissertations written about Luther in Turku one can mention the 24-page work Lutherus heros (1703) by Johannes Bernhardi Münster, professor of ethics, politics and history. This modest booklet continues the German genre of praising the heroism of the founding father of the Reformation. -

Save the Date 2013

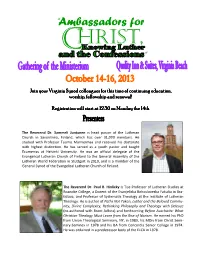

“Ambassadors for HRIST, C “ Join your Virginia Synod colleagues for this time of continuing education, worship, fellowship and renewal! Registration will start at 12:30 on Monday the 14th The Reverend Dr. Sammeli Juntunen is head pastor of the Lutheran Church in Savonlinna, Finland, which has over 31,000 members. He studied with Professor Tuomo Mannermaa and received his doctorate with highest distinction. He has served as a youth pastor and taught Ecumenics at Helsinki University. He was an official delegate of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland to the General Assembly of the Lutheran World Federation in Stuttgart in 2010, and is a member of the General Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland. The Reverend Dr. Paul R. Hinlicky is Tise Professor of Lutheran Studies at Roanoke College, a Docent of the Evanjelicka Bohoslovecka Fakulta in Bra- tislava, and Professor of Systematic Theology at the Institute of Lutheran Theology. He is author of Paths Not Taken , Luther and the Beloved Commu- nity , Divine Complexity, Rethinking Philosophy and Theology with Deleuze (co-authored with Brent Adkins) and forthcoming Before Auschwitz: What Christian Theology Must Learn from the Rise of Nazism . He earned his PhD from Union Theological Seminary, NY, in 1983, his MDiv from Christ Semi- nary-Seminex in 1978 and his BA from Concordia Senior College in 1974. He was ordained in a predecessor body of the ELCA in 1978. Ambassadors“ for HRIST “ C The Reverend Tobby Eleasar , president of the New Guinea Island District of the Evangeli- cal Lutheran Church in Papua New Guinea . Dr. Kathryn Kleinhans is Professor of Religion at Wartburg College, Waverly, Iowa, where she has taught since 1993. -

Porvoo and the Leuenberg Concord - Are They Compatible?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto PORVOO AND THE LEUENBERG CONCORD - ARE THEY COMPATIBLE? Risto Saarinen (Department of Systematic Theology, P.O. Box 33, FIN-00014 University of Helsinki, fax 358-9-19123033, email [email protected]) The Nordic Background During the 1970s the Nordic European Lutheran churches discussed intensively whether they should join the Leuenberg Concord, a continental European theological agreement which declares a church fellowship among various churches coming from Lutheran, United and Reformed traditions. After long considerations the Nordic churches did not sign the concord, although they continued to participate in the so-called Leuenberg doctrinal discussions. Reasons for this decision have largely remained unexplored. It is sometimes claimed that while the negative answer in Denmark and Norway was based on the assumption that the national church order does not easily allow for binding ecumenical agreements, the Finnish and Swedish churches had serious doubts in regard to the theology applied in the Leuenberg Concord.1) At least in the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland this was clearly the case. In May 1977 the Finnish Synod decided not to sign the Concord, although many prominent Finnish theologians, e.g. the Lutheran World Federation (LWF) President Mikko Juva, were among its supporters. The majority of the synod found that the theological method of the Concord was not acceptable; they also pointed out that the eucharistic articles of the Concord were not in agreement with Lutheran theology.2) The Finnish doubts concerning Leuenberg found an elaborate theological expression in Tuomo Mannermaa’s monograph study which appeared in Finnish 1978 and in German 1981. -

W7j65 (2003): 231-44 Is the Finnish Line a New Beginning

W7J65 (2003): 231-44 IS THE FINNISH LINE A NEW BEGINNING? A CRITICAL ASSESSMENT OF THE READING OF LUTHER OFFERED BY THE HELSINKI CIRCLE* CARL R. TRUEMAN he 1998 collection of essays on the Finnish perspective on Luther, edited Tby Carl Braaten and Robert Jenson, is both a fascinating contribution to modern ecumenical debates and an interesting challenge to accepted interpre- tations of Luther's theology. Many of the issues raised are extremely complex and a short paper such as this cannot aspire to do much more than offer a few passing comments and criticisms on the whole.1 The context of the collection is the ecumenical dialogue between the Evan- gelical Lutheran Church of Finland and the Russian Orthodox Church.2 While we must beware of reading too much significance into this context in terms of research outcomes, it undoubtedly shapes the contours of debate in which the protagonists engage. Tuomo Mannermaa and his colleagues in the "Helsinki Circle" are clearly driven by a desire to find in Luther's writings more ecumeni- cal potential with reference to Lutheran-Orthodox relations than has typically been assumed to be available. That the research of the Finns has borne just such fruit, and is significant precisely because it is pragmatically so useful for ecumenical relations, is confirmed with great and unmitigated enthusiasm by Robert Jenson in his own response to the group's work.3 Without wishing to endorse all of the enthusiasm which surrounds the Hel- sinki Circle, I would like to note at the start a number of points at which this group makes extremely valid points and thus renders a useful contribution to the wider field of Luther interpretation. -

Justification and Theosis (Deification) the Joint Declaration On

248 Piero Codø reciproco (cf. Gv 13,31-35;15,I2-I3), riflesso e realizzaztone antropologi ca delle relazioni d' amore vissute nella Santissima Trinità, è dunque chiamataa scoprire in Maria il suo archetipo e la sua for- ma generatrice. Solo così, dove si vive l'agápe secondo 1o stile di Maria, il corpo di cristo viene anche esistenzialmente configurato, a parlire dalla grazia sacramentale, come koinonìa che annuncia, teitimonia e dona cristo salvatore al mondo. La vita di Maria, plasmata e condotta dallo Spirito, sia nel suo itinerario terreno sia nell'esercizio della sua missione dal seno della Trinità ov'è assunta, è sempre e solo un "lasciar che qccada" nella storia della salvezza I'awento del Dio uno e trino salvezza della storia. Justification and Theosis Mi pare, in tal senso, che vada attentamente meditata I'afîerunazione che troviamo nella descrizione dellatetza parte del (deification) "segreto" di Fatima: "E vedemmo in una Luce immensa che è ts, simbolico-profetica del significato D io . .." cui segue una narr azione The on della storia del '900 per la chiesa. Tutto è visto in Dio. La storia Joint Declaration umana, con i suoi drammi e le sue tragedie, palcoscenico della libertà umana, è avvolta, penetrata e indirizzata dall'amore del Padre che Justification and the Dialogue ha inviato il Figlio suo nella carne, nato da Maria, e lo Spirito Santo. come scrive il card. Ratzinger: "Da quando Dio stesso ha un cuore between East and'West umano ed ha così rivolto la libertà dell'uomo verso il bene, verso Dio, la libertà per il male non ha più l'ultima parola. -

Tuomo Mannermaa *29.9.1937 †19.1.2015

Kuva Yliopistolainen. Tuomo Mannermaa *29.9.1937 †19.1.2015 elsingin yliopiston teologisen tie- Tuomo Mannermaan vaikuttamistyö pe- dekunnan emeritusprofessori ja rustui julkaisujen ohella aivan erityisesti Hsuomalaisen kristillisyyden voima- kykyyn luoda pitkäaikaisia ja aatteelliselta kas vaikuttaja Tuomo Mannermaa kuoli pit- vaikutukseltaan syvällisiä opettaja-oppilas- kään sairastettuaan Espoossa 19. tammi- suhteita. Suomalaisen teologian kansainvä- kuuta 2015. Mannermaa syntyi Oulussa 29. listymistä Mannermaa edisti yhteistyössään syyskuuta 1937 ja tuli ylioppilaaksi vuonna Mainzin Euroopan historian instituutin se- 1957 Oulun lyseosta. Hän valmistui teologi- kä amerikkalaisen Center for Catholic and an kandidaatiksi Helsingissä vuonna 1964 Evangelical Theology:n kanssa. Monista ja jäi pysyvästi Helsingin yliopiston teolo- Mannermaan oppilaista tuli merkittäviä vai- gisen tiedekunnan palvelukseen, ensin as- kuttajia yliopistossa, kirkossa ja koko suo- sistenttina ja apulaisprofessorina sekä malaisessa yhteiskunnassa. 1980–2000 ekumeniikan professorina. Köö- Kansainvälisesti Tuomo Mannermaa tun- penhaminan yliopiston kunniatohtorin ar- netaan niin kutsutun uuden suomalaisen von hän sai vuonna 2000. Suomalaisen Tie- Luther-tutkimuksen alullepanijana ja sen deakatemian jäseneksi professori Manner- keskeisten ajatusten muotoilijana. Hän maa valittiin vuonna 1986. omistautui koko professorikautensa ajan Mannermaa oli yliopistouransa ohella aivan erityisesti Luther-tutkimukselle ja poikkeuksellisen aktiivinen vaikuttaja Suo- saavutti sen -

One for Knowlege Bank

Seeking Reconciliation Without Capitulation: The History of Justification in Lutheran-Roman Catholic Dialogue Undergraduate Research Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with honors research distinction in History in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Gregory McCollum The Ohio State University May 2018 Project Advisor: Professor David Brakke, Department of History McCollum !1 Introduction In 1999, the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity and the Lutheran World Federation claimed to have reached a “high degree of agreement” on the doctrine of justification with the signing of the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification.1 Catholics and Lutherans, the document claimed, could “articulate a common understanding” of justification that “encompass[es] a consensus on basic truths of the doctrine” (JD §5). So great was this agreement on justification, which was of “central importance” to the Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century, that the Joint Declaration declared that the “remaining differences” between the communions’ understanding of justification are today “no longer the occasion for doctrinal condemnations (JD §1,5).” The anathemas and condemnations relating to justification that the two churches issued during the sixteenth century are no longer considered to apply to the two communions’ understanding of justification today. The Joint Declaration claims that the doctrinal condemnations of the 16th century, in so far as they relate to the doctrine of justification, appear in a new light: The teaching of the Lutheran churches presented in this Declaration does not fall under the condemnations from the Council of Trent. The condemnations in the Lutheran Confessions do not apply to the teaching of the Roman Catholic Church presented in this Declaration (JD §41). -

Remarks on Tuomo Mannermaa's Interpretation of Martin Luther's

Remarks on Tuomo Mannermaa’s Interpretation of Martin Luther’s Lectures on Galatians Miikka Ruokanen hen introducing new Finnish research on Luther, Risto Saarinen W points out in his recent book Luther and the Gift: ”I believe that the critics are right on this point: we do have a program but we also have to work it out in more detail.”1 And then Saarinen goes on making his own proposal to outline such a theological program which is closely related with Risto’s philosophy and theology of giving which we have learned, for instance, from his book God and the Gift: An Ecumenical Theology of Giving.2 In the following, I intend to offer my little contribution to the discussion on how to work out in more detail the Finnish interpretation of Luther. I will make some remarks on Tuomo Mannermaa’s interpretation of Luther’s doctrine of grace in his Lectures on Galatians. My comments are linked with my analysis of Luther’s De servo arbitrio in my forthcoming book The Trinitarian Doctrine of Grace in Martin Luther’s The Bondage of the Will. The more comprehensive and detailed justification of my argumentation represented in the article at hand can be found in this book.3 Tuomo Mannermaa’s analysis of Luther’s Lectures on Galatians (1531/1535) establishes the idea of the justification of the sinner through 1 Saarinen 2017, 182. 2 Saarinen 2005. Saarinen pointed to the potential of elaborating the Finnish Luther interpretation in terms of the theology of giving also in his article in The Oxford Handbook of Martin Luther’s Theology; see Saarinen 2014. -

Five Types of Lutheran Confessional Theology

Five Types of Lutheran Confessional Theology Five Types of Lutheran Confessional Theology: Toward a Method of Lutheran Confessional Theology in America for the Twenty-First Century Erik Thorstein Reid Samuelson Three Trees Press Berkeley, California The Press of the Society of the Three Trees publishes books and periodicals in support of the aims of the society: support of Pacific Lutheran Theological Seminary and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, continued study of the Bible and the Lutheran Confessions, and discernment and support of call among all ministers of the Church, lay and ordained. www.threetreespress.com Copyright © 2006 by Erik T. R. Samuelson Portions of this manuscript are copyright © 2006 Blackwell Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the author. Queries regarding rights and permissions should be addressed to: [email protected] Cover artwork: Altar of St. Mary’s Church, Wittenberg, Germany. Painted in 1547 by Lucas Cranach the Elder. Manufactured in the United States of America. For James D. Holloway (1960-2001) and Timothy F. Lull (1943-2003) Doctors of the Church CONTENTS Chapter I: Introduction 1 Chapter II: Five Centuries of Interpretations and Uses of the Confessional Documents 6 Lutheran Confessions: Context and Purpose 6 Lutheran Confessions in the Sixteenth Century