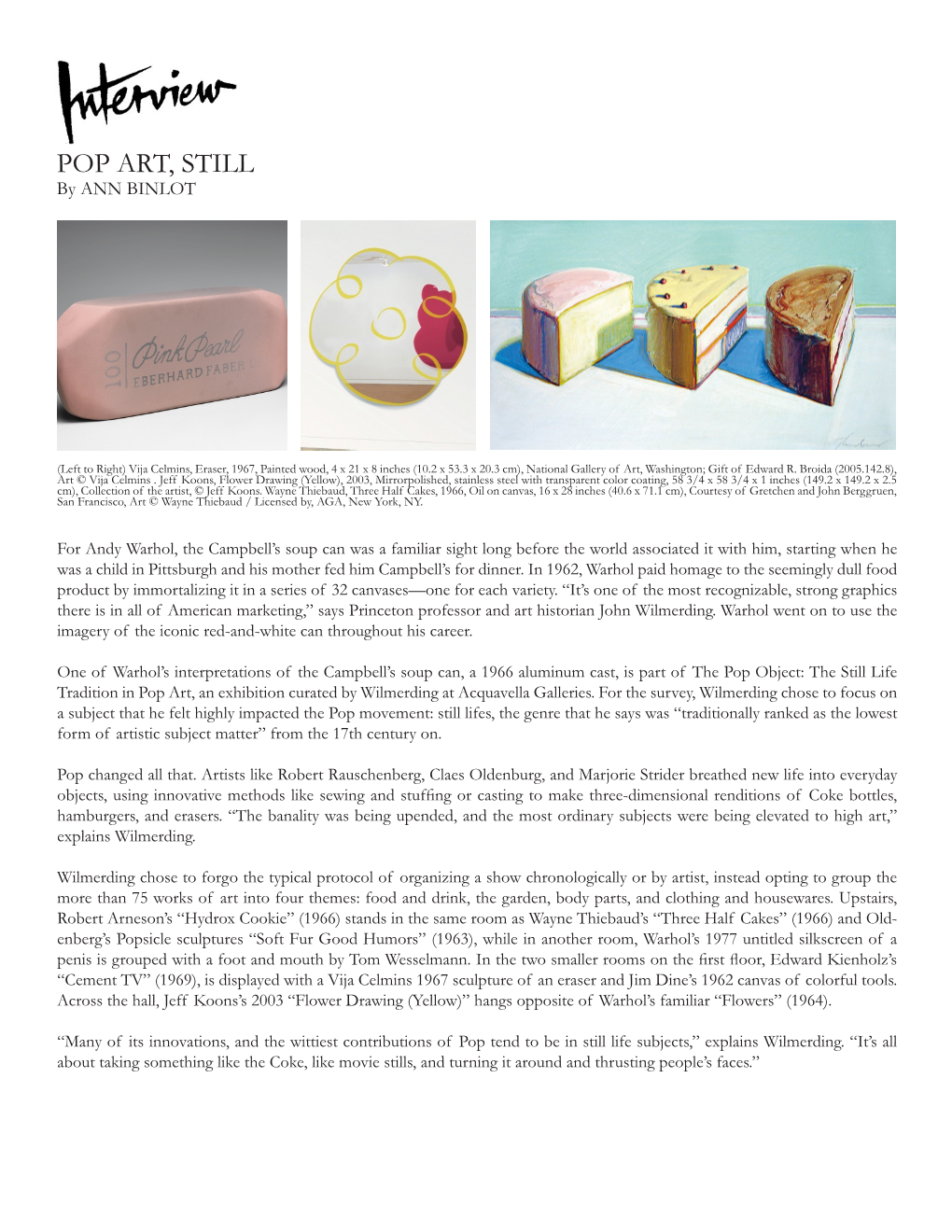

POP ART, STILL by ANN BINLOT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hans Ulrich Obrist a Brief History of Curating

Hans Ulrich Obrist A Brief History of Curating JRP | RINGIER & LES PRESSES DU REEL 2 To the memory of Anne d’Harnoncourt, Walter Hopps, Pontus Hultén, Jean Leering, Franz Meyer, and Harald Szeemann 3 Christophe Cherix When Hans Ulrich Obrist asked the former director of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Anne d’Harnoncourt, what advice she would give to a young curator entering the world of today’s more popular but less experimental museums, in her response she recalled with admiration Gilbert & George’s famous ode to art: “I think my advice would probably not change very much; it is to look and look and look, and then to look again, because nothing replaces looking … I am not being in Duchamp’s words ‘only retinal,’ I don’t mean that. I mean to be with art—I always thought that was a wonderful phrase of Gilbert & George’s, ‘to be with art is all we ask.’” How can one be fully with art? In other words, can art be experienced directly in a society that has produced so much discourse and built so many structures to guide the spectator? Gilbert & George’s answer is to consider art as a deity: “Oh Art where did you come from, who mothered such a strange being. For what kind of people are you: are you for the feeble-of-mind, are you for the poor-at-heart, art for those with no soul. Are you a branch of nature’s fantastic network or are you an invention of some ambitious man? Do you come from a long line of arts? For every artist is born in the usual way and we have never seen a young artist. -

Annual Report 2019-2020

Chicano Studies Research Center Annual Report 2019-20 Submitted by Director Chon A. Noriega 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. DIRECTOR’S MESSAGE 3 II. DEVELOPMENT REPORT 8 III. ADMINISTRATION, STAFF, FACULTY, AND ASSOCIATES 10 IV. ACADEMIC AND COMMUNITY RELATIONS 13 V. LIBRARY AND ARCHIVE 22 VI. PRESS 37 VII. RESEARCH 51 VIII. FACILITIES 65 APPENDICES 67 2 I. DIRECTOR’S MESSAGE The UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center (CSRC) was founded in 1969 with a commitment to foster multi-disciplinary research as part of the overall mission of the university. It is one of four ethnic studies centers within the Institute of American Cultures (IAC), which reports to the UCLA Office of the Chancellor. The CSRC is also a co-founder and serves as the official archive of the Inter-University Program for Latino Research (IUPLR, est. 1983), a consortium of Latino research centers that now includes twenty-four institutions dedicated to increasing the number of scholars and intellectual leaders conducting Latino-focused research. The CSRC houses a library and special collections archive, an academic press, externally-funded research projects, community-based partnerships, competitive grant and fellowship programs, and several gift funds. It maintains a public programs calendar on campus; at local, national, and international venues; and online. The CSRC also maintains strategic research partnerships with UCLA schools, departments, and research centers, as well as with major museums across the U.S. The CSRC holds six (6) positions for faculty that are appointed in academic departments. These appointments expand the CSRC’s research capacity as well as the curriculum in Chicana/o and Latina/o studies across UCLA. -

Marcel Broodthaers 1969 Galerie Gerda Bassenge

Antiquariat Querido – Frank Hermann Kunst nach 1945 Roßstraße 13 · 40476 Düsseldorf · Tel. +49 2 11 / 15 96 96 01 Fotografi e · Architektur · Design · Kunst bis 1945 Blücherstraße 7 · 40477 Düsseldorf · Tel. +49 2 11 / 51 50 23 34 Mo bis 17.00 Uhr / Di + Fr bis 15.00 Uhr, Mi + Do bis 19.00 Uhr und nach Vereinbarung Live in your head [email protected] www.antiquariat-querido.de Stadtsparkasse Düsseldorf SWIFT-BIC: DUSSDEDDXXX Antiquariat Querido · Roßstraße 13 · 40476 Düsseldorf IBAN: DE 38 3005 0110 0010 1833 66 Kunst nach 1945 USt-ID-Nr. DE 171/397705 StNr. 105/5108/1390 Künstlerbücher · Galeriekataloge · Künstlermonografi en Werkverzeichnisse · Einladungskarten · Plakate Editionen · Multiple · Grafi ken Die angebotenen Titel sind in guter bis sehr guter Erhaltung. Etwaige Mängel sind möglichst detailliert beschrieben. Alle Bücher können in unserem Ladenlokal Roßstraße 13 angesehen werden. Das Angebot ist freibleibend, Lieferzwang besteht nicht. Die Bestellungen werden in der Reihenfolge des Eingangs ausgeführt. Alle Preise verstehen sich in Euro. Der Versand erfolgt zu Lasten und Risiko des Bestellers, telefonisch erfolgte Bestellung bitten wir per E-Mail oder Fax zu bestätigen. Bei begründeter Beanstandung wird jede Lieferung innerhalb 14 Tagen zurückgenommen. Eigentumsvorbehalte nach § 455 BGB. Erfüllungsort und Gerichtsstand ist Düsseldorf. Rechnungen sind zahlbar innerhalb 14 Tagen ohne Abzüge. Wir sind stets am Erwerb von Büchern unserer Fachgebiete interessiert und kaufen Einzelstücke wie auch ganze Bibliotheken. Wir freuen uns über Ihre Angebote. Antiquariat Querido · Blücherstraße 7 · 40477 Düsseldorf Fotografi e · ArchitekturKatalog 10 · Design · Kunst bis 1945 All items are in fi ne condition, unless otherwise stated. Please ask for specifi c description by e-mail Monografi en und Kataloge zu: Fotografi e im 20. -

Pop Culture and Art

Colorado Teacher-Authored Instructional Unit Sample Visual Arts 6th Grade Unit Title: Pop Culture and Art INSTRUCTIONAL UNIT AUTHORS Pueblo County School District Amie Holmberg Brenna Reedy Colorado State University Patrick Fahey, PhD BASED ON A CURRICULUM OVERVIEW SAMPLE AUTHORED BY Denver School District Capucine Chapman Fountain School District Sean Norman Colorado’s District Sample Curriculum Project This unit was authored by a team of Colorado educators. The template provided one example of unit design that enabled teacher- authors to organize possible learning experiences, resources, differentiation, and assessments. The unit is intended to support teachers, schools, and districts as they make their own local decisions around the best instructional plans and practices for all students. DATE POSTED: MARCH 31, 2014 Colorado Teacher-Authored Sample Instructional Unit Content Area Visual Arts Grade Level 6th Grade Course Name/Course Code Sixth Grade Visual Arts Standard Grade Level Expectations (GLE) GLE Code 1. Observe and Learn to 1. The characteristics and expressive features of art and design are used in unique ways to respond to two- and VA09-GR.6-S.1-GLE.1 Comprehend three-dimensional art 2. Art created across time and cultures can exhibit stylistic differences and commonalities VA09-GR.6-S.1-GLE.2 3. Specific art vocabulary is used to describe, analyze, and interpret works of art VA09-GR.6-S.1-GLE.3 2. Envision and Critique to 1. Visual symbols and metaphors can be used to create visual expression VA09-GR.6-S.2-GLE.1 Reflect 2. Key concepts, issues, and themes connect the visual arts to other disciplines such as the humanities, sciences, VA09-GR.6-S.2-GLE.1 mathematics, social studies, and technology 3. -

Encyklopédia Kresťanského Umenia

Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia americká architektúra - pozri chicagská škola, prériová škola, organická architektúra, Queen Anne style v Spojených štátoch, Usonia americká ilustrácia - pozri zlatý vek americkej ilustrácie americká retuš - retuš americká americká ruleta/americké zrnidlo - oceľové ozubené koliesko na zahnutej ose, užívané na zazrnenie plochy kovového štočku; plocha spracovaná do čiarok, pravidelných aj nepravidelných zŕn nedosahuje kvality plochy spracovanej kolískou americká scéna - american scene americké architektky - pozri americkí architekti http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:American_women_architects americké sklo - secesné výrobky z krištáľového skla od Luisa Comforta Tiffaniho, ktoré silno ovplyvnili európsku sklársku produkciu; vyznačujú sa jemnou farebnou škálou a novými tvarmi americké litografky - pozri americkí litografi http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:American_women_printmakers A Anne Appleby Dotty Atti Alicia Austin B Peggy Bacon Belle Baranceanu Santa Barraza Jennifer Bartlett Virginia Berresford Camille Billops Isabel Bishop Lee Bontec Kate Borcherding Hilary Brace C Allie máj "AM" Carpenter Mary Cassatt Vija Celminš Irene Chan Amelia R. Coats Susan Crile D Janet Doubí Erickson Dale DeArmond Margaret Dobson E Ronnie Elliott Maria Epes F Frances Foy Juliette mája Fraser Edith Frohock G Wanda Gag Esther Gentle Heslo AMERICKÁ - AMES Strana 1 z 152 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia Charlotte Gilbertson Anne Goldthwaite Blanche Grambs H Ellen Day -

Tom Wesselmann Programs and Statewide Offerings

COMMUNICATIONS & MARKETING VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS 200 N. Boulevard I Richmond, Virginia 23220-4007 www.vmfa.museum/pressroom I T 804.204.2704 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 21, 2013 Tom Wesselmann Programs and Statewide Offerings American artist Tom Wesselmann (1931-2004) is one of the leading figures in the American Pop Art movement with a career spanning more than four decades. Opening April 6, VMFA offers the first comprehensive North American retrospective of Wesselmann’s work. VMFA is the only East Coast venue for this exhibition. In honor of Pop Art and Beyond: Tom Wesselmann, the museum is offering programs, lectures, self- directed tours and more. Student groups, K–College: Self-directed student group tours are available for Pop Art and Beyond: Tom Wesselmann, seven days a week, April 6 – July 28, 2013. Please note: This is not a guided tour. Cost: Group tickets are $12 per student, with one chaperone for every 10 students admitted free. Additional chaperones are $12 each. VMFA members are free, but tickets are required. Audio guides of this exhibition are also available at $5 per person. Please call Tour Services at 804.340.1419 or visit: http://www.vmfa.state.va.us/Learn/Educators/Self-guided_Tours.aspx Smoker #1, 1967. Oil on shaped canvas, in two parts, 9.87 x 7.1 in. © The Museum of Adult Groups Modern Art, New York/Estate of Tom Self-directed student adult tours are available for Pop Art and Beyond: Tom Wesselmann/Licensed by VAGA, New Wesselmann, seven days a week, April 6 – July 28, 2013. -

Axell, Pauline Boty and Rosalyn Drexler

Downloaded from Pop’s Ladies and Bad Girls: Axell, Pauline Boty andkall Rosalyn Drexler ioaj.oxfordjournals.org Kalliopi Minioudaki daki at University of California, Irvine on October 3, 2010 Downloaded from oaj.oxfordjournals.org at University of California, Irvine on October 3, 2010 Pop’s Ladies and Bad Girls: Axell, Pauline Boty and Rosalyn Drexler Kalliopi Minioudaki Dada must have something to do with Pop ... the names are really synonyms. (Andy Warhol1) In entertainment slang, bad girls ... describes female performers, musicians, actors and 1. G.R. Swenson, ‘What Is Pop Art’, Art News, comedians ... who challenge audiences to see women as they have been, as they are and as November 1963, pp. 24–7. they want to be ... In the visual arts, increasing numbers of women artists ... are defying the 2. Marcia Tucker, Bad Girls (New Museum of Downloaded from conventions and proprieties of traditional femininity to define themselves according ... to Contemporary Art: New York, 1994), pp. 4–6. their own pleasures ... by using a delicious and outrageous sense of humor. (Marcia Tucker2) 3. Aside from the hybrid yet still understudied case of Warhol’s Superstars. See for instance The accepted story of Pop Art, as in many modernist tales, is one of male Leanne Gilbertson, ‘Andy Warhol’s Beauty #2: 3 subjects and female objects. Its canon has relied exclusively on male Demystifying and Reabstracting the Feminine Mystique, Obliquely’, Art Journal, Spring 2003, artists whose iconography has often objectified women. Yet there were oaj.oxfordjournals.org women who were initially, or can be retroactively, associated with Pop pp. 25–33. -

RECONFIGURING POP by Saul Ostrow

RECONFIGURING POP By Saul Ostrow "Seductive Subversion: Women Pop Artists 1958-1968" is the rare show that encourages you to rethink an entire period. Curated by Sid Sachs of the Rosenwald-Wolf Gallery at University of the Arts in Philadelphia, where it premiered last winter, it is billed as the first-ever all-woman survey of Pop art. Affording us the opportunity to rediscover artists and see unfamiliar work, the show revisits the origins of Pop art and the influence wielded by popular culture internationally during the decade in question.1 In subject matter, content and esthetics, the work on view departs in surprising and significant ways from what one might expect of Pop art, and in so doing challenges much received wisdom about the movement. Marjorie Strider: Green Triptych, 1963, acrylic paint and laminated pine on Masonite, 72 by 105 inches. Collection Michael T. Chutko. In the early '60s, the term "Pop" was generally applied to art that depicted mundane objects or banal commercial products, and whose imagery and style referenced advertising or graphic design. Pop's defining exhibitions-"New Painting of Common Objects," curated by Walter Hopps at the Pasadena Art Museum; "The New Realists," at Sidney Janis Gallery in New York (both 1962); and "Six Painters and the Object," organized by Lawrence Alloway at the Guggenheim Museum (1963)-were all-male affairs (though Marisol was included in the Janis show). Sachs reminds us that there is much more to Pop-to its artistic sources and objectives-than the critical and art historical canon would lead us to believe. -

Seductive-Subversion

Ovation TV is grateful to the New York City Department of Education, Office of Arts and Special Projects, for its support of the Arts Ed Toolkit. Lesson Plan for Ovation TV documentary Seductive Subversion Grade Level – 9-12 Visual Arts (lessons) Language Arts (activity) Materials for teacher Evaluation Sheets Ovation TV’s website www.ovationtv.com/educators National Visual Arts Standards Grades 9-12 Reprinted with permission from the National Art Education Association. See www.arteducators.org * denotes selected art terms that may be found in the glossary Note: It is strongly recommended that teachers review all selected programming clips contained in these lessons, prior to using them in classes. Page | 1 1. Content Standard: Understanding and applying media, techniques, and processes Achievement Standard, Proficient: Students a. apply media, techniques, and processes with sufficient skill, confidence, and sensitivity that their intentions are carried out in their artworks b. conceive and *create works of visual art that demonstrate an understanding of how the communication of their ideas relates to the media, techniques, and processes they use Achievement Standard, Advanced: Students c. communicate ideas regularly at a high level of effectiveness in at least one visual arts medium d. initiate, define, and solve challenging *visual arts problems independently using intellectual skills such as analysis, synthesis, and evaluation 2. Content Standard: Using knowledge of *structures and functions Achievement Standard, Proficient: Students a. demonstrate the ability to form and defend judgments about the characteristics and structures to accomplish commercial, personal, communal, or other purposes of art b. evaluate the effectiveness of artworks in terms of organizational structures and functions c. -

Jean-Noel Archive.Qxp.Qxp

THE JEAN-NOËL HERLIN ARCHIVE PROJECT Jean-Noël Herlin New York City 2005 Table of Contents Introduction i Individual artists and performers, collaborators, and groups 1 Individual artists and performers, collaborators, and groups. Selections A-D 77 Group events and clippings by title 109 Group events without title / Organizations 129 Periodicals 149 Introduction In the context of my activity as an antiquarian bookseller I began in 1973 to acquire exhibition invitations/announcements and poster/mailers on painting, sculpture, drawing and prints, performance, and video. I was motivated by the quasi-neglect in which these ephemeral primary sources in art history were held by American commercial channels, and the project to create a database towards the bibliographic recording of largely ignored material. Documentary value and thinness were my only criteria of inclusion. Sources of material were random. Material was acquired as funds could be diverted from my bookshop. With the rapid increase in number and diversity of sources, my initial concept evolved from a documentary to a study archive project on international visual and performing arts, reflecting the appearance of new media and art making/producing practices, globalization, the blurring of lines between high and low, and the challenges to originality and quality as authoritative criteria of classification and appreciation. In addition to painting, sculpture, drawing and prints, performance and video, the Jean-Noël Herlin Archive Project includes material on architecture, design, caricature, comics, animation, mail art, music, dance, theater, photography, film, textiles and the arts of fire. It also contains material on galleries, collectors, museums, foundations, alternative spaces, and clubs. -

Ideas Recibidas Un Vocabulario Para La Cultura Artística Contemporánea

ideas recibidas un vocabulario para la cultura artística contemporánea Índice 105 Documento 221 Pop Documento, ficción El arte pop: repetición, y presencia del cuerpo diferencia, contingencia Gabriel Villota Toyos Juan Antonio Suárez 7 Presentación Documento y espectáculo El pop consiste en Jorge Ribalta Jean-Louis Comolli que gusten las cosas Jonathan Flatley 9 Cine 125 Gentrificación El aparato atrapado por la cola Transformaciones en las ciudades 245 Público Eugeni Bonet Josep Maria Montaner Las paradojas de la visión pública El sujeto y el dispositivo: ¿Son los museos tan solo un vehículo Marcelo Expósito del cine al ciberespacio al servicio del desarrollo inmobiliario? Sobre «público» Arlindo Machado Neil Smith Rosalyn Deutsche 31 Conceptualismo 151 Industria cultural 265 Relación De 1966 a 2008: el conceptualismo Una referencia en los estudios Un nuevo mundo de regiones en la historia del arte culturales de Gran Bretaña Francisco-J. Hernández Adrián María Ruido Mari Paz Balibrea Una nueva región del mundo Hagámoslo nosotros mismos Industria cultural Édouard Glissant Lucy Lippard Angela McRobbie 283 Subjetividad 53 Crítica 173 Museo Una ética afirmativa del devenir Nelly Richard y las itinerancias Los museos como laboratorios Raúl Sánchez Cedillo del ejercicio crítico de gubernamentalidad Afirmación, dolor y capacitación Ana Longoni Jesús Carrillo Rosi Braidotti La crítica: entre lo artístico Museo y lo cultural Tony Bennett Nelly Richard 316 Participantes 197 Performance 73 Cubo blanco Antes de Pictures: el valor Adiós al cubo blanco crítico de la memoria Carles Guerra Jesús Carrillo La poética del espacio aumentado Acción en los márgenes Lev Manovich Douglas Crimp Presentación Jorge Ribalta Este libro recoge las aportaciones a las series de conferencias que tuvieron lugar en el Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA) a lo largo de dos años consecutivos, en otoño de 2007 y 2008. -

Rosalyn Drexler Featured in the New York Times

http://nyti.ms/1amJfIH ART & DESIGN When the World Went Pop By RANDY KENNEDY APRIL 8, 2015 MINNEAPOLIS — For art lovers, and certainly for the collectors now paying tens of millions of dollars per painting at auction, Pop art and its trademark images — Marilyns, Ben-Day dots, Coca-Cola bottles, lipsticked lips — have become 20th century classicism, as canonical as Cubism and as appealing as candy. But for many artists working outside the United States during Pop’s birth in the early 1960s, the movement presented itself with all the charm of a steamroller. “In those years,” said Thomas Bayrle, a German painter who was making Mao’s portrait years before Andy Warhol did, “it was like a football match in which one side was always winning and the other side couldn’t even score a single goal.” Art history moved with unprecedented speed in defining Pop — the great curator Henry Geldzahler said it towed “instant art history” in its wake — and the narrative that unfolded in museums and books has been predominantly American, with a pioneering British adjunct. But a half-century into the movement’s existence, its map is being redrawn with a vengeance. An exhibition opening here at the Walker Art Center on Saturday, “International Pop,” one of the museum’s most ambitious historical shows in years, makes the case not only that Pop was sprouting in countless homegrown versions around the world but also that the term itself has become too narrow to encompass the revolution in thinking it represented for a generation of artists. In September, the Tate Modern in London will plow into much of the same underexplored territory with “The World Goes Pop.” Taken together, the exhibitions are likely to bring the reputations of dozens of overlooked artists — from Japan, South America, Eastern Europe and even the Middle East — into a new kind of spotlight, while showing that many well-known artists who came of age in the early 1960s were Poppier than they might have thought, or appeared.