Composers of Hollywood's Golden Age a Dissertation Submi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nature of Elliot Goldenthal's Music

The Nature of Elliot Goldenthal’s Music & A Focus on Alien 3 (& other scores) There is “something different” about Elliot Goldenthal’s music. There is also considerable brain and brawn in Elliot Goldenthal’s film music. His style is difficult to label because his approach is so eclectic depending on the project. Sometimes I feel he is fundamentally an independent art-house composer (perhaps Frida, say, and The Good Thief) although he can demonstrate thrilling orchestral power in scores such as Sphere and the Batman movies that I personally quite enjoyed. Overall he shows a Late Modernist temperament, musically an American Bohemian, but nevertheless grounded somewhat in the mainstream traditions (certainly at least traditional notation). His polystylism (eclectism) is a postmodern characteristic. An excellent example of polystylism is his score for Titus (and Good Thief to a lesser extent, and even an example or two in Alien 3) with the diverse or even odd juxtaposition of genres (symphonic-classical, rock, etc.) that represents in one score the type of projects he collectively undertook over the last fifteen years or so. There is not one clear-cut musical voice, in other words, but a mixture or fusion of different styles. It is, in part, his method of organization. Loosely speaking, his music is avant-garde but certainly not radically so--as in the case of John Cage with his aleatoric (random) music and quite non-traditional notation (although Goldenthal’s music can at select times be aleatoric in effect when he utilizes electronic music, quarter-toning, and other devices). He is experimental and freewheeling but certainly this tendency is not overblown and expanded into the infinite! He definitely takes advantage of what technology has to offer (MIDI applications, timbre sampling, synthesizer usage, etc.) but does not discard what traditions are useful for him to express his vision of musical art. -

B R I a N K I N G M U S I C I N D U S T R Y P R O F E S S I O N a L M U S I C I a N - C O M P O S E R - P R O D U C E R

B R I A N K I N G M U S I C I N D U S T R Y P R O F E S S I O N A L M U S I C I A N - C O M P O S E R - P R O D U C E R Brian’s profile encompasses a wide range of experience in music education and the entertainment industry; in music, BLUE WALL STUDIO - BKM | 1986 -PRESENT film, television, theater and radio. More than 300 live & recorded performances Diverse range of Artists & Musical Styles UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA Music for Media in NYC, Atlanta, L.A. & Paris For more information; www.bluewallstudio.com • As an administrator, professor and collaborator with USC working with many award-winning faculty and artists, PRODUCTION CREDITS - PARTIAL LIST including Michael Patterson, animation and digital arts, Medeski, Martin and Wood National Medal of Arts recipient, composer, Morton Johnny O’Neil Trio Lauridsen, celebrated filmmaker, founder of Lucasfilm and the subdudes (w/Bonnie Raitt) ILM, George Lucas, and his team at the Skywalker Ranch. The B- 52s Jerry Marotta Joseph Arthur • In music education, composition and sound, with a strong The Indigo Girls focus on establishing relations with industry professionals, R.E.M. including 13-time Oscar nominee, Thomas Newman, and 5- Alan Broadbent time nominee, Dennis Sands - relationships leading to PS Jonah internships in L.A. and fundraising projects with ASCAP, Caroline Aiken BMI, the RMALA and the Musician’s Union local 47. Kristen Hall Michelle Malone & Drag The River Melissa Manchester • In a leadership role, as program director, recruitment Jimmy Webb outcomes aligned with career success for graduates Col. -

A Note from the Composer

Toronto Symphony Orchestra Sir Andrew Davis, Interim Artistic Director Friday, December 6, 2019 at 7:30pm Saturday, December 7, 2019 at 2:00pm Saturday, December 7, 2019 at 7:30pm Constantine Kitsopoulos, conductor Resonance Youth Choir Bob Anderson, director As a courtesy to musicians, guest artists, and fellow concertgoers, please put your phone away and on silent during the performance. A NOTE FROM THE COMPOSER Ever since Home Alone appeared, it has held a unique place in the affections of a very broad public. Director Chris Columbus brought a uniquely fresh and innocent approach to this delightful story, and the film has deservedly become a perennial at holiday time. I took great pleasure in composing the score for the film, and I am especially delighted that the magnificent Toronto Symphony Orchestra has agreed to perform the music in a live presentation of the movie. I know I speak for everyone connected with the making of the film in saying that we are greatly honoured by this event…and I hope that the audience at this performance will experience the renewal of joy that the film brings with it, each and every year. John Williams DECEMBER 6 & 7, 2019 17 TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX Presents A JOHN HUGHES Production A CHRIS COLUMBUS Film HOME ALONE Starring MACAULAY CULKIN JOE PESCI DANIEL STERN JOHN HEARD and CATHERINE O’HARA Music by JOHN WILLIAMS Film Editor RAJA GOSNELL Production Designer JOHN MUTO Director of Photography JULIO MACAT Executive Producers MARK LEVINSON & SCOTT ROSENFELT and TARQUIN GOTCH Written and Produced by JOHN HUGHES Directed by CHRIS COLUMBUS Soundtrack Album Available on CBS Records, Cassettes and Compact Discs Color by DELUXE® Tonight’s program is a presentation of the complete filmHome Alone with a live performance of the film’s entire score, including music played by the orchestra during the end credits. -

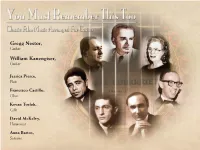

Gregg Nestor, William Kanengiser

Gregg Nestor, Guitar William Kanengiser, Guitar Jessica Pierce, Flute Francisco Castillo, Oboe Kevan Torfeh, Cello David McKelvy, Harmonica Anna Bartos, Soprano Executive Album Producers for BSX Records: Ford A. Thaxton and Mark Banning Album Produced by Gregg Nestor Guitar Arrangements by Gregg Nestor Tracks 1-5 and 12-16 Recorded at Penguin Recording, Eagle Rock, CA Engineer: John Strother Tracks 6-11 Recorded at Villa di Fontani, Lake View Terrace, CA Engineers: Jonathan Marcus, Benjamin Maas Digitally Edited and Mastered by Jonathan Marcus, Orpharian Recordings Album Art Direction: Mark Banning Mr. Nestor’s Guitars by Martin Fleeson, 1981 José Ramirez, 1984 & Sérgio Abreu, 1993 Mr. Kanengiser’s Guitar by Miguel Rodriguez, 1977 Special Thanks to the composer’s estates for access to the original scores for this project. BSX Records wishes to thank Gregg Nestor, Jon Burlingame, Mike Joffe and Frank K. DeWald for his invaluable contribution and oversight to the accuracy of the CD booklet. For Ilaine Pollack well-tempered instrument - cannot be tuned for all keys assuredness of its melody foreshadow the seriousness simultaneously, each key change was recorded by the with which this “concert composer” would approach duo sectionally, then combined. Virtuosic glissando and film. pizzicato effects complement Gold's main theme, a jaunty, kaleidoscopic waltz whose suggestion of a Like Korngold, Miklós Rózsa found inspiration in later merry-go-round is purely intentional. years by uniting both sides of his “Double Life” – the title of his autobiography – in a concert work inspired by his The fanfare-like opening of Alfred Newman’s ALL film music. Just as Korngold had incorporated themes ABOUT EVE (1950), adapted from the main title, pulls us from Warner Bros. -

BBC Four Programme Information

SOUND OF CINEMA: THE MUSIC THAT MADE THE MOVIES BBC Four Programme Information Neil Brand presenter and composer said, “It's so fantastic that the BBC, the biggest producer of music content, is showing how music works for films this autumn with Sound of Cinema. Film scores demand an extraordinary degree of both musicianship and dramatic understanding on the part of their composers. Whilst creating potent, original music to synchronise exactly with the images, composers are also making that music as discreet, accessible and communicative as possible, so that it can speak to each and every one of us. Film music demands the highest standards of its composers, the insight to 'see' what is needed and come up with something new and original. With my series and the other content across the BBC’s Sound of Cinema season I hope that people will hear more in their movies than they ever thought possible.” Part 1: The Big Score In the first episode of a new series celebrating film music for BBC Four as part of a wider Sound of Cinema Season on the BBC, Neil Brand explores how the classic orchestral film score emerged and why it’s still going strong today. Neil begins by analysing John Barry's title music for the 1965 thriller The Ipcress File. Demonstrating how Barry incorporated the sounds of east European instruments and even a coffee grinder to capture a down at heel Cold War feel, Neil highlights how a great composer can add a whole new dimension to film. Music has been inextricably linked with cinema even since the days of the "silent era", when movie houses employed accompanists ranging from pianists to small orchestras. -

Radio TV Mirror

JANICE GILBERT The girl who gave away MIRRO $3,000,000! ARTHUR GODFREY BROOK BYRON BETTY LU ANN SIMMS ANN GROVE ! ^our new Lilt home permaTient will look , feel and stay like the loveliest naturally curly hair H.1 **r Does your wave look as soft and natural as the Lilt girl in our picture? No? Then think how much more beautiful you can be, when you change to Lilt with its superior ingredients. You'll be admired by men . envied by women ... a softer, more charming you. Because your Lilt will look, feel and stay like naturally curly hair. Watch admiring eyes light up, when you light up your life with a Lilt. $150 Choose the Lilt especially made for your type of hair! plus tax Procter £ Gambles new Wt guiJ. H Home Permanent tor hard-to-wave hair for normal hair for easy-to-wave hair for children's hair — . New, better way to reduce decay after eating sweets Always brush with ALL- NEW IPANA after eating ... as the Linders do . the way most dentists recommend. New Ipana with WD-9 destroys tooth-decay bacteria.' s -\V 77 If you eat sweet treats (like Stasia Linder of Massa- Follow Stasia Linder's lead and use new Ipana regularly pequa, N. Y., and her daughter Darryl), here's good news! after eatin g before decay bacteria can do their damage. You can do a far better job of preventing cavities by Even if you can't always brush after eating, no other brushing after eatin g . and using remarkable new Ipana tooth paste has ever been proved better for protecting Tooth Paste. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Lowell E. Graham 1058 Eagle Ridge El Paso, Texas 79912 Residence Work Home e-mail (915) 581-9741 (915) 747-7825 [email protected] Education Doctor of Musical Arts, Catholic University of America, 1977, Orchestral Conducting Graduate Studies in Music, University of Missouri at Kansas City, summers 1972 and 1973 Master of Arts, University of Northern Colorado, 1971, Clarinet Performance Bachelor of Arts, University of Northern Colorado, 1970, Music Education Military Professional Education Air War College, 1996 Air Command and Staff College, 1983 Squadron Officer School, 1977 Work Experience 2009 to Present Director of Orchestral Activities Music Director, UTEP Symphony Orchestra University of Texas at El Paso El Paso, Texas As the Director or Orchestral Activities I am responsible for the training and development of major orchestral ensembles at the university. I began a tradition of featuring faculty soloists as well as winners of the annual student Concerto Competition, now with an award offered by Olivas Music, providing the orchestra the opportunity to perform significant concerto literature as well as learning the art of accompanying. In 2012, I developed a new chamber orchestra called the “UTEP Virtuosi” focusing on significant string orchestra repertoire. I initiated a concert featuring music in movies and for stage in which that music is presented and integrated via multimedia with lectures and video. It has become the capstone event for the year featuring the artistry of faculty soloists and comments per classical music used in movies and music composed exclusively for that medium. Each year six performances are scheduled. Repertoire for each year covers all eras and styles. -

A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughn Williams and Britten Through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums

A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughn Williams and Britten through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Jensen, Joni Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 05/10/2021 21:33:53 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/193556 A COMPARISON OF ORIGINS AND INFLUENCES IN THE MUSIC OF VAUGHAN WILLIAMS AND BRITTEN THROUGH ANALYSIS OF THEIR FESTIVAL TE DEUMS by Joni Lynn Jensen Copyright © Joni Lynn Jensen 2005 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC AND DANCE In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS WITH A MAJOR IN MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 5 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Joni Lynn Jensen entitled A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughan Williams and Britten through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Bruce Chamberlain _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Elizabeth Schauer _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Josef Knott Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. -

Contemporary Film Music

Edited by LINDSAY COLEMAN & JOAKIM TILLMAN CONTEMPORARY FILM MUSIC INVESTIGATING CINEMA NARRATIVES AND COMPOSITION Contemporary Film Music Lindsay Coleman • Joakim Tillman Editors Contemporary Film Music Investigating Cinema Narratives and Composition Editors Lindsay Coleman Joakim Tillman Melbourne, Australia Stockholm, Sweden ISBN 978-1-137-57374-2 ISBN 978-1-137-57375-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-57375-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017931555 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017 The author(s) has/have asserted their right(s) to be identified as the author(s) of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

Final Appendices

Bibliography ADORNO, THEODOR W (1941). ‘On Popular Music’. On Record: Rock, Pop and the Written Word (ed. S Frith & A Goodwin, 1990): 301-314. London: Routledge (1publ. in Philosophy of Social Sci- ence, 9. 1941, New York: Institute of Social Research: 17-48). —— (1970). Om musikens fetischkaraktär och lyssnandets regression. Göteborg: Musikvetenskapliga in- stitutionen [On the fetish character of music and the regression of listening]. —— (1971). Sociologie de la musique. Musique en jeu, 02: 5-13. —— (1976a). Introduction to the Sociology of Music. New York: Seabury. —— (1976b) Musiksociologi – 12 teoretiska föreläsningar (tr. H Apitzsch). Kristianstad: Cavefors [The Sociology of Music – 12 theoretical lectures]. —— (1977). Letters to Walter Benjamin: ‘Reconciliation under Duress’ and ‘Commitment’. Aesthetics and Politics (ed. E Bloch et al.): 110-133. London: New Left Books. ADVIS, LUIS; GONZÁLEZ, JUAN PABLO (eds., 1994). Clásicos de la Música Popular Chilena 1900-1960. Santiago: Sociedad Chilena del Derecho de Autor. ADVIS, LUIS; CÁCERES, EDUARDO; GARCÍA, FERNANDO; GONZÁLEZ, JUAN PABLO (eds., 1997). Clásicos de la música popular chilena, volumen II, 1960-1973: raíz folclórica - segunda edición. Santia- go: Ediciones Universidad Católica de Chile. AHARONIÁN, CORIúN (1969a). Boom-Tac, Boom-Tac. Marcha, 1969-05-30. —— (1969b) Mesomúsica y educación musical. Educación artística para niños y adolescentes (ed. Tomeo). 1969, Montevideo: Tauro (pp. 81-89). —— (1985) ‘A Latin-American Approach in a Pioneering Essay’. Popular Music Perspectives (ed. D Horn). Göteborg & Exeter: IASPM (pp. 52-65). —— (1992a) ‘Music, Revolution and Dependency in Latin America’. 1789-1989. Musique, Histoire, Dé- mocratie. Colloque international organisé par Vibrations et l’IASPM, Paris 17-20 juillet (ed. A Hennion. -

The Musical Contexts GCSE Music Study and Revision Guide For

GCSE MUSIC – FILM MUSIC S T U D Y A N D REVISION GUIDE The Musical Contexts GCSE Music Study and Revision Guide for Film Music Designed to support: Eduqas GCSE Music – Area of Study 3: Film Music OCR GCSE Music – Area of Study 4: Film Music Pearson Edexcel GCSE Music – Area of Study: Music for Stage and Screen P a g e 1 o f 32 © WWW.MUSICALCONTEXTS.CO.UK GCSE MUSIC – FILM MUSIC S T U D Y A N D REVISION GUIDE The Purpose of Film Music Film Music is a type of DESCRIPTIVE MUSIC that represents a mood, story, scene or character through music; it is designed to support the action and emotions of the film on screen. Film music serves many different purposes including: 1. To create or enhance a mood 2. To function as a LEITMOTIF 3. To link one scene to another providing continuity 4. To emphasise a gesture (known as MICKEY-MOUSING) 5. To give added commercial impetus 6. To provide unexpected juxtaposition or to provide irony 7. To illustrate geographic location or historical period 8. To influence the pacing of a scene 1. To create or enhance a mood Music aids (and is sometimes essential to effect) the suspension of our disbelief: film attempts to convince us that what we are seeing is really happening and music can help break down any resistance we might have. It can also comment directly on the film, telling us how to respond to the action. Music can also enhance a dramatic effect: the appearance of a monster in a horror film, for example, rarely occurs without a thunderous chord! Sound effects (like explosions and gunfire) can be incorporated into the film soundtrack to create a feeling of action and emotion, particularly in war films. -

Alban Berg's Filmic Music

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 Alban Berg's filmic music: intentions and extensions of the Film Music Interlude in the Opera Lula Melissa Ursula Dawn Goldsmith Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Goldsmith, Melissa Ursula Dawn, "Alban Berg's filmic music: intentions and extensions of the Film Music Interlude in the Opera Lula" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2351. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2351 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. ALBAN BERG’S FILMIC MUSIC: INTENTIONS AND EXTENSIONS OF THE FILM MUSIC INTERLUDE IN THE OPERA LULU A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The College of Music and Dramatic Arts by Melissa Ursula Dawn Goldsmith A.B., Smith College, 1993 A.M., Smith College, 1995 M.L.I.S., Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, 1999 May 2002 ©Copyright 2002 Melissa Ursula Dawn Goldsmith All rights reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is my pleasure to express gratitude to my wonderful committee for working so well together and for their suggestions and encouragement. I am especially grateful to Jan Herlinger, my dissertation advisor, for his insightful guidance, care and precision in editing my written prose and translations, and open mindedness.