Metoo Means Who?: Shining a Light on the Darkness a Rhetorical Analysis of Inclusivity and Exclusivity Within the #Metoo Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protecting Children in Virtual Worlds Without Undermining Their Economic, Educational, and Social Benefits

Protecting Children in Virtual Worlds Without Undermining Their Economic, Educational, and Social Benefits Robert Bloomfield* Benjamin Duranske** Abstract Advances in virtual world technology pose risks for the safety and welfare of children. Those advances also alter the interpretations of key terms in applicable laws. For example, in the Miller test for obscenity, virtual worlds constitute places, rather than "works," and may even constitute local communities from which standards are drawn. Additionally, technological advances promise to make virtual worlds places of such significant social benefit that regulators must take care to protect them, even as they protect children who engage with them. Table of Contents I. Introduction ................................................................................ 1177 II. Developing Features of Virtual Worlds ...................................... 1178 A. Realism in Physical and Visual Modeling. .......................... 1179 B. User-Generated Content ...................................................... 1180 C. Social Interaction ................................................................. 1180 D. Environmental Integration ................................................... 1181 E. Physical Integration ............................................................. 1182 F. Economic Integration ........................................................... 1183 * Johnson Graduate School of Management, Cornell University. This Article had its roots in Robert Bloomfield’s presentation at -

A New #Metoo Result: Rejecting Notions of Romantic Consent with Executives

Texas A&M University School of Law Texas A&M Law Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 1-2019 A New #MeToo Result: Rejecting Notions of Romantic Consent with Executives Michael Z. Green Texas A & M University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar Part of the Labor and Employment Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael Z. Green, A New #MeToo Result: Rejecting Notions of Romantic Consent with Executives, 23 Emp. Rts. & Emp. Pol'y J. 115 (2019). Available at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar/1389 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Texas A&M Law Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Texas A&M Law Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A NEW #METOO RESULT: REJECTING NOTIONS OF ROMANTIC CONSENT WITH EXECUTIVES BY MICHAEL Z. GREEN* I. INTRODUCTION: #METOO AND THE GROWING DEBATE ON LEGAL CONSENT......................................... ..... 116 II. #METOO AND THE VILE USE OF POWER-DIFFERENTIAL BY EXECUTIVE HARASSERS ........................... ...... 121 III. #METOO BACKLASH AND CLAIMS OF UNCERTAINTY ABOUT WORKPLACE CONSENT ...................................... 126 A. Increasing "Unwelcome" Sexual Harassment Claims as a Result of #MeToo. ........................... ..... 126 B. Resulting Backlash Based on Consent and Unfair Process.......130 C. Dating at Work Being Unnecessarily Regulated........................135 D. Duplicitous Responses Based on Politics ......... ....... 136 E. The Aziz Ansari Experience. .......................... 139 F. Women as the Violators....................... 144 G. Much More Ado Than Should Be Due in the Workplace........... 145 IV. #METoo AND THE BACKBONE TO COME FORWARD DESPITE EXECUTIVE RETALIATION ............................... -

The Rules of #Metoo

University of Chicago Legal Forum Volume 2019 Article 3 2019 The Rules of #MeToo Jessica A. Clarke Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Clarke, Jessica A. (2019) "The Rules of #MeToo," University of Chicago Legal Forum: Vol. 2019 , Article 3. Available at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol2019/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Chicago Legal Forum by an authorized editor of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Rules of #MeToo Jessica A. Clarke† ABSTRACT Two revelations are central to the meaning of the #MeToo movement. First, sexual harassment and assault are ubiquitous. And second, traditional legal procedures have failed to redress these problems. In the absence of effective formal legal pro- cedures, a set of ad hoc processes have emerged for managing claims of sexual har- assment and assault against persons in high-level positions in business, media, and government. This Article sketches out the features of this informal process, in which journalists expose misconduct and employers, voters, audiences, consumers, or professional organizations are called upon to remove the accused from a position of power. Although this process exists largely in the shadow of the law, it has at- tracted criticisms in a legal register. President Trump tapped into a vein of popular backlash against the #MeToo movement in arguing that it is “a very scary time for young men in America” because “somebody could accuse you of something and you’re automatically guilty.” Yet this is not an apt characterization of #MeToo’s paradigm cases. -

P22 Layout 1

22 Established 1961 Tuesday, January 22, 2019 Lifestyle Features Russian row over ‘Siege of Leningrad’ black comedy “blasphemous” re-telling of one of the darkest Leningrad to the Nazis in order to save millions of lives?” moments in Soviet history or a much-needed it asked. Acomment on modern Russia? A new comedy set during the Siege of Leningrad has divided the country’s ‘The toughest of times’ This file photo viewers. “Prazdnik” or “Holiday” tells of the Some who lived through the blockade told AFP they shows Italian #MeToo’s Voskresensky family, whose Communist Party connec- were horrified by the concept of the film. “I just can’t actress Asia Argento tions allow them to live a life of luxury in a city encir- imagine that there could be a comedy about the siege,” arriving for the clos- cled by Nazis. During a siege in which some 800,000 said Lidia Ilyinskaya. “I’m 88 years old and I cry every ing ceremony of the people starved to death on official rations of 125 grams 71st edition of the Asia Argento of bread a day, they pile their table high with chicken Cannes Film Festival and champagne to celebrate New Year 1942. in Cannes, southern to model in A slick comedy of manners ensues when the two France. — AFP Voskresensky children bring home unexpected guests, and the family are forced to explain how their table is laid with a festive spread. Award-winning director Alexei Krasovsky Paris fashion show told AFP the film was made to draw attention to inequali- ties and injustices in Russia today, rather than make light of the siege. -

Art, Argento and the Rape-Revenge Film

University of Edinburgh Postgraduate Journal of Culture and the Arts Issue 13 | Autumn 2011 Title The Violation of Representation: Art, Argento and the Rape-Revenge Film Author Alexandra Heller-Nicholas Publication FORUM: University of Edinburgh Postgraduate Journal of Culture and the Arts Issue Number 13 Issue Date Autumn 2011 Publication Date 6/12/2011 Editors Dorothy Butchard & Barbara Vrachnas FORUM claims non-exclusive rights to reproduce this article electronically (in full or in part) and to publish this work in any such media current or later developed. The author retains all rights, including the right to be identified as the author wherever and whenever this article is published, and the right to use all or part of the article and abstracts, with or without revision or modification in compilations or other publications. Any latter publication shall recognise FORUM as the original publisher. FORUM | ISSUE 13 Alexandra Heller-Nicholas 1 The Violation of Representation: Art, Argento and the Rape-Revenge Film Alexandra Heller-Nicholas Swinburne University of Technology Considering the moral controversies surrounding films such as I Spit on Your Grave (Meir Zarch, 1976) and Baise-Moi (Virginie Despentes and Coralie Trinh-Thi, 2000), the rape-revenge film is often typecast as gratuitous and regressive. But far from dismissing rape-revenge in her foundational book Men, Women and Chain Saws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film (1992), Carol J. Clover suggests that these movies permit unique insight into the representation of gendered bodies on screen. In Images of Rape: The ‘Heroic’ Tradition and Its Alternatives (1999), art historian Diane Wolfthal demonstrates that contradictory representations of sexual violence co-existed long before the advent of the cinematic image, and a closer analysis of films that fall into the rape-revenge category reveals that they too resist a singular classification. -

Radiocorrieretv SETTIMANALE DELLA RAI RADIOTELEVISIONE

RadiocorriereTv SETTIMANALE DELLA RAI RADIOTELEVISIONE ITALIANA numero 10 - anno 90 8 marzo 2021 Reg. Trib. n. 673 del 16 dicembre 1997 MANESKIN TRIONFO ROCK ©Maurizio D'Avanzo NELLE LIBRERIE E STORE DIGITALI Nelle librerie e store digitali 2 TV RADIOCORRIERE 3 3 Nelle librerie PERCHE’ SANREMO e store digitali È SANREMO Sanremo è finito. Viva Sanremo. Come ogni anno ci sono vincitori e vinti, ci sono critiche e commenti, applausi e fischi, anche in questa edizione da remoto. Poi ci sono loro. I dipendenti di questa azienda, a volte bistrattata, ma sempre presenti, con forza, capacità e soprattutto con tanta dignità. E allora grazie a tutte, ma proprio tutte, le maestranze della Rai che ancora una volta hanno messo in campo tutto quello che potevano lavorando anche in condizioni di grandissima difficoltà. Grazie a chi ha lasciato per settimane i propri affetti, in questo periodo non era facile, per trasferirsi a lavorare in una città molto diversa da quella glamour e festante degli anni passati. Un lavoro certosino, meticoloso come sempre, solo come quello che i tecnici e giornalisti Rai sanno fare quando sono chiamati a giocare finali. Questo Festival ha portato rispetto e forse non lo ha ricevuto del tutto. Non era facile calarsi con garbo in un periodo fatto di sofferenze e paure. Cercare di entrare nelle case degli italiani spaventati. Per una settimana si è provato a far riscoprire quel desiderio di normalità misto a fiducia. Cinque serate di evasione, di riflessione, ma anche di speranza che il mondo della musica, dello spettacolo, possano tornare quanto prima a regalare emozioni. -

La Giuria Di X Factor 2018: Fedez, Mara Maionchi

MARTEDì 29 MAGGIO 2018 X Factor 2018 ha la sua giuria: saranno Fedez, Mara Maionchi, Manuel Agnelli e Asia Argentoa sedere al tavolo della prossima edizione del talent show di Sky, prodotto da FremantleMedia Italia. Confermatissimo La giuria di X Factor 2018: Fedez, alla conduzione Alessandro Cattelan. Mara Maionchi, Manuel Agnelli e Asia Argento "Siamo molto felici di ritrovare Fedez a Mara, due fuoriclasse il cui ritorno era confermato da qualche tempo, e molto soddisfatti che Manuel si sia convinto a non prendersi una pausa e rinnovare il suo impegno in questa grande avventura, una presenza, la sua, della quale X Factor non può fare ANTONIO GALLUZZO a meno dopo l'eccellente lavoro fatto in questi due anni - ha dichiarato Nils Hartmann, Direttore produzioni originali di Sky Italia. E siamo entusiasti di dare il benvenuto ad Asia nella famiglia di X Factor, dove siamo certi che il contributo della sua cultura musicale e personalità sarà importantissimo. Asia con Fedez, Mara e Manuel comporranno una straordinaria nuova squadra capace di individuare e coltivare le [email protected] potenzialità dei talenti che incontreranno. SPETTACOLINEWS.IT Alessandro Cattelan con il suo talento saprà poi, ancora una volta, garantire uno straordinario ritmo allo show" "Diamo il benvenuto a tutti i protagonisti di questa nuova edizione, e in particolare ad Asia Argento, che siamo felicissimi di avere a bordo. - ha affermato Gabriele Immirzi, Direttore Generale FremantleMedia Italia - X Factor 2018 inizia nel segno di un ulteriore rinnovamento creativo e produttivo, con l'ambizione di continuare a crescere ed essere sempre di più il punto riferimento degli show musicali italiani e internazionali" Asia si appresta così ad affrontare una nuova sfida, nella sua pluridecennale e multiforme carriera ha spaziato dal cinema, dove è regista e autrice, alla tv, e alla musica, con una visione unica, spaziando nel mondo industrial ed elettropop. -

HIAS Report Template

Roadmap to Recovery A Path Forward after the Remain in Mexico Program March 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................ 1 The Stories of MPP .................................................................................................. 1 Our Work on the Border ......................................................................................... 2 Part One: Changes and Challenges at the Southern Border ................................. 4 Immigration Under the Trump Administration ...................................................... 5 How MPP Worked ................................................................................................... 9 Situation on the Ground ......................................................................................... 12 Nonrefoulement Interviews .................................................................................... 18 Effects on the Legal Cases ....................................................................................... 19 Lack of Access to Legal Counsel .............................................................................. 20 The Coronavirus Pandemic and Title 42 ................................................................. 20 Part Two: Recommendations ................................................................................ 22 Processing Asylum Seekers at Ports of Entry .......................................................... 23 Processing -

The Me Too Movement

TOPIC 2018 #metoo The Me Too Movement A PRIZE TO BE AWARDED AT SPEECH NIGHT • Seeking an outstanding essay that addresses Theissues IGS of globalGlobal complexity Scholar’s and significance •Prize Open Winningto students in EssayYears 10, 11 and 12 TOPIC 2018 The Me Too Movement In an environment like Hollywood that places such a high value on sex, the people who possess the most power treat it so casually. But then again, what else could be expected of a society that perpetuates the belief that sex sells? Across the world, outraged women and seen change clearly only see Hollywood. men who refuse to allow their stories to Because while there is more dialogue and be silenced any longer are speaking out conversation about sexual assault and following the #MeToo movement, a mass gender-based violence now than ever global movement sparked by a single before in Western culture, there is little hashtag. And, as to be expected of 21st to no change happening in developing century Western society, the prime focus nations. When we think of #MeToo stories, of this movement seems to be Hollywood. our minds leap to the words of the likes of But amidst the exposure of the grim Taylor Swift and Simone Biles. We do not reality of Hollywood’s not-so-glamorous think of 8-year-old Afisa Bano, an Indian behind the scenes, many of us seem to be girl who was kidnapped, repeatedly raped forgetting those who cannot tell their own then bludgeoned to death in January. We stories, who need our attention the most. -

Post-Cinematic Affect: on Grace Jones, Boarding Gate and Southland Tales

Film-Philosophy 14.1 2010 Post-Cinematic Affect: On Grace Jones, Boarding Gate and Southland Tales Steven Shaviro Wayne State University Introduction In this text, I look at three recent media productions – two films and a music video – that reflect, in particularly radical and cogent ways, upon the world we live in today. Olivier Assayas’ Boarding Gate (starring Asia Argento) and Richard Kelly’s Southland Tales (with Justin Timberlake, Dwayne Johnson, Seann William Scott, and Sarah Michelle Gellar) were both released in 2007. Nick Hooker’s music video for Grace Jones’s song ‘Corporate Cannibal’ was released (as was the song itself) in 2008. These works are quite different from one another, in form as well as content. ‘Corporate Cannibal’ is a digital production that has little in common with traditional film. Boarding Gate, on the other hand, is not a digital work; it is thoroughly cinematic, in terms both of technology, and of narrative development and character presentation. Southland Tales lies somewhat in between the other two. It is grounded in the formal techniques of television, video, and digital media, rather than those of film; but its grand ambitions are very much those of a big-screen movie. Nonetheless, despite their evident differences, all three of these works express, and exemplify, the ‘structure of feeling’ that I would like to call (for want of a better phrase) post-cinematic affect. Film-Philosophy | ISSN: 1466-4615 1 Film-Philosophy 14.1 2010 Why ‘post-cinematic’? Film gave way to television as a ‘cultural dominant’ a long time ago, in the mid-twentieth century; and television in turn has given way in recent years to computer- and network-based, and digitally generated, ‘new media.’ Film itself has not disappeared, of course; but filmmaking has been transformed, over the past two decades, from an analogue process to a heavily digitised one. -

Newsletter 15/10 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 15/10 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 278 - September 2010 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 11 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 15/10 (Nr. 278) September 2010 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, auch jede Menge Filme auf dem liebe Filmfreunde! Fantasy Filmfest inspiziert. Diese sind Herzlich willkommen zum ersten jedoch in seinem Blog nicht enthalten, Newsletter nach unserer Sommer- sondern werden wie üblich zu einem pause. Es ist schon erstaunlich, wie späteren Zeitpunkt in einem separaten schnell so ein Urlaub vorbeigehen Artikel besprochen werden. Als ganz kann. Aber wie sollten wir es auch besonderes Bonbon werden wir in ei- merken? Denn die meiste Zeit ha- ner der nächsten Ausgaben ein exklu- ben wir im Kino verbracht. Unser sives Interview mit dem deutschstäm- Filmblogger Wolfram Hannemann migen Regisseur Daniel Stamm prä- hat es während dieser Zeit immer- sentieren, das unser Filmblogger wäh- hin auf satte 61 Filme gebracht! Da rend des Fantasy Filmfests anlässlich bleibt nicht viel Zeit für andere Ak- des Screenings von Stamms Film DER tivitäten, zumal einer der gesichte- LETZTE EXORZISMUS geführt ten Filme mit einer Lauflänge von 5 hat. ½ Stunden aufwartete. Während wir dieses Editorial schreiben ist er Sie sehen – es bleibt spannend! schon längst wieder dabei, Filmein- führungen für das bevorstehende Ihr Laser Hotline Team 70mm-Filmfestival der Karlsruher Schauburg zu schreiben. Am 1. Ok- tober geht’s los und hält uns und viele andere wieder für drei ganze Tage und Nächte auf Trab. -

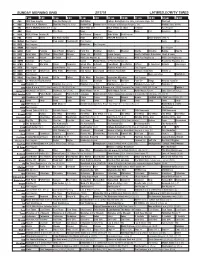

Sunday Morning Grid 2/17/19 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/17/19 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Bull Riding College Basketball Ohio State at Michigan State. (N) PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Hockey Day Hockey New York Rangers at Pittsburgh Penguins. (N) Hockey: Blues at Wild 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid American Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb Paid Program 1 1 FOX Planet Weird Fox News Sunday News PBC Face NASCAR RaceDay (N) 2019 Daytona 500 (N) 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Freethought Paid Program News Paid 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Christina Baking How To 2 8 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Curios -ity Biz Kid$ Grand Canyon Huell’s California Adventures: Huell & Louie 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva (N) 4 0 KTBN Jeffress Win Walk Prince Carpenter Intend Min.