The Maenclochog Community Excavation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women in the Rural Society of South-West Wales, C.1780-1870

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses Women in the rural society of south-west Wales, c.1780-1870. Thomas, Wilma R How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Thomas, Wilma R (2003) Women in the rural society of south-west Wales, c.1780-1870.. thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa42585 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ Women in the Rural Society of south-west Wales, c.1780-1870 Wilma R. Thomas Submitted to the University of Wales in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of History University of Wales Swansea 2003 ProQuest Number: 10805343 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Autumn / Winter 2013 River Special Area of Conservation (SAC) – Concentrating on the Area from the Source of the Afon Syfynwy to the Dam at Llys Y Frân

Llys y Frân Catchment Project Work began on the Llys y Frân Catchment Pro- ject in July. This new initiative, led by Afonydd Cymru in association with Pembrokeshire Riv- ers Trust, is a trial collaborative partnership with Dŵr Cymru Welsh Water and Natural Re- sources Wales (NRW). The project is based on the Afon Syfynwy catchment, a tributary of the Eastern Cleddau, which drains into the Rosebush and Llys y Frân Volume 10 Issue 3 Reservoirs and lies within the Eastern Cleddau Autumn / Winter 2013 River Special Area of Conservation (SAC) – concentrating on the area from the source of the Afon Syfynwy to the dam at Llys y Frân. In this Issue Llys y Frân Reservoir has been susceptible to Llys y Frân Catchment Blue Green Algae blooms in recent years. The Project project aims to achieve a better understanding Pages 1 & 2 of factors impacting on water quality and nutri- ent loading within the catchment in relation to Hedgehogs in land use, looking at activities such as forestry Pembrokeshire operations, sewage inputs and farming. It is Pages 2 - 4 hoped that this initiative will deliver positive measures to help improve water quality, mini- mise the risk of pollution incidents and help to Habitat for Rare Dragonfly gain favourable conservation status. Saved Pages 4 - 5 Rare Fish Caught in the Haven Pages 5 - 6 Wildlife Trust Supports Local Charcoal Maker Pages 6 - 7 Hang on to your Tackle! Pages 8 - 9 Courses and Events Pages 10 - 11 Contact details Blue Green Algae at Llys y Frân Page12 Photo: Natural Resources Wales Ant Rogers — Biodiversity Implementation Officer [email protected] 01437764551 Page 1 Further information about the project can be obtained by emailing the Catchment Project Officer, Ro Rogers at: [email protected] Pembrokeshire Rivers Trust is always keen to recruit new volunteers. -

The Fates of the Princes of Dyfed Cenydd Morus (Kenneth Morris) Illustrations by Reginald Machell

Theosophical University Press Online Edition The Fates of the Princes of Dyfed Cenydd Morus (Kenneth Morris) Illustrations by Reginald Machell Copyright © 1914 by Katherine Tingley; originally published at Point Loma, California. Electronic edition 2000 by Theosophical University Press ISBN 1- 55700-157-x. This edition may be downloaded for off-line viewing without charge. For ease of searching, no diacritical marks appear in the electronic version of the text. To Katherine Tingley: Leader and Official Head of the Universal Brotherhood and Theosophical Society, whose whole life has been devoted to the cause of Peace and Universal Brotherhood, this book is respectfully dedicated Contents Preface The Three Branches of the Bringing-in of it, namely: The Sovereignty of Annwn I. The Council of the Immortals II. The Hunt in Glyn Cuch III. The Slaying of Hafgan The Story of Pwyll and Rhianon, or The Book of the Three Trials The First Branch of it, called: The Coming of Rhianon Ren Ferch Hefeydd I. The Making-known of Gorsedd Arberth, and the Wonderful Riding of Rhianon II. The First of the Wedding-Feasts at the Court of Hefeydd, and the Coming of Gwawl ab Clud The Second Branch of it, namely: The Basket of Gwaeddfyd Newynog, and Gwaeddfyd Newynog Himself I. The Anger of Pendaran Dyfed, and the Putting of Firing in the Basket II. The Over-Eagerness of Ceredig Cwmteifi after Knowledge, and the Putting of Bulrush-Heads in the Basket III. The Circumspection of Pwyll Pen Annwn, and the Filling of the Basket at Last The First Branch of it again: III. -

Maenclochog Countryside Smaller Settlements Associated Settlement

Potential site analysis for site 388, Rosebush - Near Belle Vue Associated settlement Countryside LDP settlement tier Smaller settlements Community Council area Maenclochog Site area (hectares) 0.33 Site register reference(s) (if proposed as development site for LDP) No LDP site registration Relationship to designated areas Not within 100500 metres of a SSSI.SAC. Not within 500 metres of a SPA. Not within 500 metres of a National Nature Reserve. Not within 100 metres of a Local Nature Reserve. Not within 500 metres of a Marine Nature Reserve. Not within 100 metres of a Woodland Trust Nature Reserve. Not within 100 metres of a Wildlife Trust Nature Reserve. Not within 100 metres of Access Land. Not within 100 metres of a Scheduled Ancient Monument. Not within 50 metres of a Listed Building. NotPartly within within 100 a Historicmetres ofLandscape a Conservation Area. Area. Not within 100 metres of a Historic Garden. Not within 50 metres of Contaminated Land. Not within airfield safeguarding zones for buildings under 15m high. Not within HSE safeguarding zones. Not within MoD safeguarding zones for buildings under 15m high. Not within 10 metres of a Tree Protection Order. Not within 100 metres of ancient or semi-natural woodland. Underlying Agricultural Land Classification: 4 (1 is Agriculturally most valuable, 5 is least valuable). Not within a quarry buffer zone. Not within safeguarded route for roads or cycleways. Site includes Public Right of Way. Not a Village Green. Report prepared on 30 November 2009 Page 1 of 5 Stage one commentary Site is not wholly within a Site of Special Scientific Interest; Natura 2000 site; National, Local, Marine, Woodland Trust or Wildlife Trust nature reserve; or Scheduled Ancient Monument. -

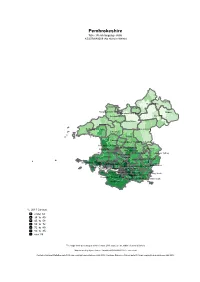

Pembrokeshire Table: Welsh Language Skills KS207WA0009 (No Skills in Welsh)

Pembrokeshire Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0009 (No skills in Welsh) Cilgerran St. Dogmaels Goodwick Newport Fishguard North West Fishguard North East Clydau Scleddau Crymych Dinas Cross Llanrhian St. David's Solva Maenclochog Letterston Wiston Camrose Haverfordwest: Prendergast,Rudbaxton Haverfordwest: Garth Haverfordwest: Portfield Haverfordwest: Castle Narberth Martletwy Haverfordwest: Priory Narberth Rural Lampeter Velfrey Merlin's Bridge Johnston The Havens Llangwm Kilgetty/Begelly Amroth Milford: North Burton St. Ishmael's Neyland: West Milford: WestMilford: East Milford: Hakin Milford: Central Saundersfoot Milford: Hubberston Neyland: East East Williamston Pembroke Dock:Pembroke Market Dock: Central Carew Pembroke Dock: Pennar Penally Pembroke Dock: LlanionPembroke: Monkton Tenby: North Pembroke: St. MaryLamphey North Manorbier Pembroke: St. Mary South Pembroke: St. Michael Tenby: South Hundleton %, 2011 Census under 34 34 to 45 45 to 58 58 to 72 72 to 80 80 to 85 over 85 The maps show percentages within Census 2011 output areas, within electoral divisions Map created by Hywel Jones. Variables KS208WA0022−27 corrected Contains National Statistics data © Crown copyright and database right 2013; Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2013 Pembrokeshire Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0010 (Can understand spoken Welsh only) St. Dogmaels Cilgerran Goodwick Newport Fishguard North East Fishguard North West Crymych Clydau Scleddau Dinas Cross Llanrhian St. David's Letterston Solva Maenclochog Haverfordwest: Prendergast,Rudbaxton Wiston Camrose Haverfordwest: Garth Haverfordwest: Castle Haverfordwest: Priory Narberth Haverfordwest: Portfield The Havens Lampeter Velfrey Merlin's Bridge Martletwy Narberth Rural Llangwm Johnston Kilgetty/Begelly St. Ishmael's Milford: North Burton Neyland: West East Williamston Amroth Milford: HubberstonMilford: HakinMilford: Neyland:East East Milford: West Saundersfoot Milford: CentralPembroke Dock:Pembroke Central Dock: Llanion Pembroke Dock: Market Penally LampheyPembroke:Carew St. -

Existing Electoral Arrangements

COUNTY OF PEMBROKESHIRE EXISTING COUNCIL MEMBERSHIP Page 1 2012 No. OF ELECTORS PER No. NAME DESCRIPTION ELECTORATE 2012 COUNCILLORS COUNCILLOR 1 Amroth The Community of Amroth 1 974 974 2 Burton The Communities of Burton and Rosemarket 1 1,473 1,473 3 Camrose The Communities of Camrose and Nolton and Roch 1 2,054 2,054 4 Carew The Community of Carew 1 1,210 1,210 5 Cilgerran The Communities of Cilgerran and Manordeifi 1 1,544 1,544 6 Clydau The Communities of Boncath and Clydau 1 1,166 1,166 7 Crymych The Communities of Crymych and Eglwyswrw 1 1,994 1,994 8 Dinas Cross The Communities of Cwm Gwaun, Dinas Cross and Puncheston 1 1,307 1,307 9 East Williamston The Communities of East Williamston and Jeffreyston 1 1,936 1,936 10 Fishguard North East The Fishguard North East ward of the Community of Fishguard and Goodwick 1 1,473 1,473 11 Fishguard North West The Fishguard North West ward of the Community of Fishguard and Goodwick 1 1,208 1,208 12 Goodwick The Goodwick ward of the Community of Fishguard and Goodwick 1 1,526 1,526 13 Haverfordwest: Castle The Castle ward of the Community of Haverfordwest 1 1,651 1,651 14 Haverfordwest: Garth The Garth ward of the Community of Haverfordwest 1 1,798 1,798 15 Haverfordwest: Portfield The Portfield ward of the Community of Haverfordwest 1 1,805 1,805 16 Haverfordwest: Prendergast The Prendergast ward of the Community of Haverfordwest 1 1,530 1,530 17 Haverfordwest: Priory The Priory ward of the Community of Haverfordwest 1 1,888 1,888 18 Hundleton The Communities of Angle. -

Camrose Community Audit

Heartlands Hub Heritage and Natural Environment Audit Part B Camrose Community Audit For: PLANED May 2012 Heartlands Hub Heritage and Natural Environment Audit Part B Camrose Community Audit By Jenny Hall, MIfA & Paul Sambrook, MIfA Trysor Trysor Project No. 2011/230 For: PLANED May 2012 Cover photograph: Camrose Baptist Chapel, 2012 Heartlands Hub Heritage & Natural Resources Audit Camrose Community RHIF YR ADRODDIAD - REPORT NUMBER: Trysor 2011/230 DYDDIAD 4ydd Mai 2012 DATE 4th May 2012 Paratowyd yr adroddiad hwn gan bartneriad Trysor. Mae wedi ei gael yn gywir ac yn derbyn ein sêl bendith. This report was prepared by the Trysor partners. It has been checked and received our approval. JENNY HALL MIfA Jenny Hall PAUL SAMBROOK MIfA Paul Sambrook DYDDIAD DATE 04/05/2012 Croesawn unrhyw sylwadau ar gynnwys neu strwythur yr adroddiad hwn. We welcome any comments on the content or structure of this report. 38, New Road, Treclyn Gwaun-cae-Gurwen Eglywswrw Ammanford Crymych Carmarthenshire Pembrokeshire SA18 1UN SA41 3SU 01269 826397 01239 891470 www.trysor.net [email protected] CONTENTS 1. Community Overview 1 Landscape and Geology 1 2. Natural Heritage (Designatons and Attractions) 3 3. Heritage (Archaeology, History and Culture) 5 Heritage Overview 5 Designated Heritage Sites and Areas 9 List of Sites by Period 10 Cultural Sites 12 4. Interpretation 14 5. Tourism-Related Commerce 15 6. Observations 18 7. Camrose Heritage Gazetteer Index 20 8. Camrose Heritage Gazetteer 24 9. Camrose Culture Gazetteer 91 10. Camrose Natural Attractions Gazetteer 96 Camrose Heritage & Natural Resources Audit CAMROSE COMMUNITY 1. COMMUNITY OVERVIEW Camrose is a large, inland community, covering an area of 45.92km2, see Figure 1. -

The Development of Key Characteristics of Welsh Island Cultural Identity and Sustainable Tourism in Wales

SCIENTIFIC CULTURE, Vol. 3, No 1, (2017), pp. 23-39 Copyright © 2017 SC Open Access. Printed in Greece. All Rights Reserved. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.192842 THE DEVELOPMENT OF KEY CHARACTERISTICS OF WELSH ISLAND CULTURAL IDENTITY AND SUSTAINABLE TOURISM IN WALES Brychan Thomas, Simon Thomas and Lisa Powell Business School, University of South Wales Received: 24/10/2016 Accepted: 20/12/2016 Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper considers the development of key characteristics of Welsh island culture and sustainable tourism in Wales. In recent years tourism has become a significant industry within the Principality of Wales and has been influenced by changing conditions and the need to attract visitors from the global market. To enable an analysis of the importance of Welsh island culture a number of research methods have been used, including consideration of secondary data, to assess the development of tourism, a case study analysis of a sample of Welsh islands, and an investigation of cultural tourism. The research has been undertaken in three distinct stages. The first stage assessed tourism in Wales and the role of cultural tourism and the islands off Wales. It draws primarily on existing research and secondary data sources. The second stage considered the role of Welsh island culture taking into consideration six case study islands (three with current populations and three mainly unpopulated) and their physical characteristics, cultural aspects and tourism. The third stage examined the nature and importance of island culture in terms of sustainable tourism in Wales. This has involved both internal (island) and external (national and international) influences. -

Little Haven Conservation Area Proposals

LittleHaven_proposals_Layout 1 18/10/2011 12:38 Page 1 Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Authority Little Haven Conservation Area Proposals Supplementary Planning Guidance to the Local Development Plan for the Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Adopted 12 October 2011 LittleHaven_proposals_Layout 1 18/10/2011 12:38 Page 1 LITTLE HAVEN CONSERVATION AREA PROPOSALS CONTENTS PAGE NO. FOREWORD . 3 1. Introduction. 5 2. Character Statement Synopsis . 7 3. SWOT Analysis. 11 4. POST Analysis . 15 5. Resources . 18 6. Public Realm . 20 7. Traffic Management. 22 8. Community Projects. 23 9. Awareness . 24 10. Development . 25 11. Control . 26 12. Study & Research. 27 13. Boundaries . 28 14. Next Steps . 30 15. Programme . 31 16. Abbreviations Used . 32 Appendix A: Key to Conservation Area Features Map October 2011 LittleHaven_proposals_Layout 1 18/10/2011 12:38 Page 2 PEMBROKESHIRE COAST NATIONAL PARK Poppit A 487 Aberteifi Bae Ceredigion Llandudoch Cardigan Cardigan Bay St. Dogmaels AFON TEIFI A 484 Trewyddel Moylegrove Cilgerran A 487 Nanhyfer Nevern Dinas Wdig Eglwyswrw Boncath Pwll Deri Goodwick Trefdraeth Felindre B 4332 Newport Abergwaun Farchog Fishguard Aber-mawr Cwm Gwaun Crosswell Abercastle Llanychaer Gwaun Valley B 4313 Trefin Bryniau Preseli Trevine Mathry Presely Hills Crymych Porthgain A 40 Abereiddy Casmorys Casmael Mynachlog-ddu Castlemorris Croesgoch W Puncheston Llanfyrnach E Treletert S Rosebush A 487 T Letterston E B 4330 R Caerfarchell N C L Maenclochog E Tyddewi D Cas-blaidd Hayscastle DAU Wolfscastle B 4329 B 4313 St Davids Cross Ambleston Llys-y-fran A 487 Country Park Efailwen Solfach Spittal EASTERN CLEDDAU Solva Treffgarne Newgale A 478 Scolton Country Park Llandissilio Llanboidy Roch Camrose Ynys Dewi Ramsey Island Clunderwen Simpson Cross Clarbeston Road St. -

Provider Town ABC Pre-School Nursery Haverfordwest Amanda

Provider Town ABC Pre-School Nursery Haverfordwest Amanda Davies St Florence Childcare Tenby Amanda's Registered Childcare Tenby Amy's Acorns Childminding Pembroke Dock Anne-Marie Hancock Haverfordwest Arabella’s Childminding KILGETTY Beverley Raymond Haverfordwest Bloomfield After School and Holiday Club Narberth Breda Griffiths, Childminding Services Fishguard Bright Start Day Nursery Haverfordwest Broad Haven Playgroup Haverfordwest Busy Beehive Haverfordwest Camrose and Roch Playgroup Haverfordwest Claire John Childminding Narberth CLAIRE LAVINIA SMITH HAVERFORDWEST Claudia’s Childminding Tenby Coastlands CP School Club Haverfordwest Crwban Bach Crymych Cubs Corner Pre-School Nursery Haverfordwest Cylch Meithrin Bwlchygroes Llanfyrnach Cylch Meithrin Arbeth Narberth Cylch Meithrin Abergwaun Abergwaun Cylch Meithrin Caer Elen (Hwlffordd) Haverfordwest Cylch Meithrin Croesgoch Haverfordwest Cylch Meithrin Crymych Crymych Cylch Meithrin Hermon Crymych Cylch Meithrin Llandysilio Clunderwen Cylch Meithrin Tonnau Bach Tenby Cylch Meithrin Eglwyswrw Eglwyswrw Cylch Meirthin Maenclochog Maenclochog Cylch Meithrin Ysgol Cilgerran Cilgerran Delyth Bryan Clarbeston Road Doodles Childminding Milford Haven Elizabeth McSweeney Haverfordwest Felicity Baker Childminding Cardigan Golden Manor Nursery Pembroke Happy Days Childcare Centre Milford Haven Milford Haven Happy Days Haverfordwest Haverfordwest Happy Feet Childminding Tenby Happy House Childminding Milford Haven Heathers Childminding Sevice Kilgetty Hook's Little Diamonds HAVERFORDWEST Isobel -

Vorlan, Maenclochog Clynderwen SA66 7LH Offers in the Region of £380,000

Vorlan, Maenclochog Clynderwen SA66 7LH Offers in the region of £380,000 • 5 Bed Period Smallholding • Set in Approx 5 Acres • Secluded,Gently Sloping Land Large Barn and Static Caravan with Services • EPC Rating D John Francis is a trading name of John Francis (Wales) Ltd which is Authorised and Regulated by the Financial Services Authority. We endeavour to make our sales details accurate and reliable but they should not be relied on as statements or representations of fact and they do not constitute any part of an offer or contract. The seller does not make any representation to give any warranty in relation to the property and we have no authority to do so on behalf of the seller. Any information given by us in these details or otherwise is given without responsibility on our part. Services, Đttings and equipment referred to in the sales details have not been tested (unless otherwise stated) and no warranty can be given as to their condition. We strongly recommend that all the information which we provide about the property is veriĐed by yourself or your advisers. Please contact us before viewing the property. If there is any point of particular importance to you we will be pleased to provide additional information or to make further enquiries. We will also conĐrm that the property remains available. This is particularly important if you are contemplating travelling some distance to view the property. Double glazed window to side 22'6 x 14'4 (6.86m x 4.37m) DESCRIPTION and rear, double glazed door 2 Velux style windows, double A RARE OPPORTUNITY TO to side, inglenook fireplace glazed window to rear. -

Post Medieval and Modern

A Research Framework for the Archaeology of Wales Select Bibliography, Southwest Wales Post Medieval and Modern A Research Framework for the Archaeology of Wales Southwest Wales – Post Medieval, bibliography 22/12/2003 This list is drawn from a number of sources : a small number derive from the original audit by Cambria Archaeology; more from a trawl through Ceredigion County Library, Aberystwyth; some from published bibliographies, but most from an incomplete search of current periodical literature. The compiler does not claim to have run all these to earth at first hand, so some page references, the names of publishers and some places of publication are missing. It should be noted that not all apparently authoritative published bibliographies - on the web and off it - are necessarily as complete as might be expected. Some may be biased by the interests or prejudices of their compilers. The Website on Mining Bilbiography is a good example. It excludes certain materials on processing and hydrology, and omits virtually everything the present writer has written on dating mines! The present writer regrets if his equally subjective selection inadvertently omits anything significant to the interests of its readers, but welcomes notification of it. Bibliographical Sources Dyfed 1990. Dyfed Llayfryddiaeth Ddethol: A Select Reading List, Adran Gwasanaethau Diwylliannol: Cultural Services Department. [This is a very useful document as far as it goes. However, it is carelessly edited and rather thin on archaeology]. Jones, G. Lewis, u. D. (c1968) A Bibliography of Cardiganshire, Cardiganshire Joint Library Committee. General BBC Wales Southwest website. Cadw 1998. Register of Landscapes of Outstanding Historic Interest in Wales, Cadw: Cardiff.