This Is Normal Text

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Historic Recordings of the Song Desafinado: Bossa Nova Development and Change in the International Scene1

The historic recordings of the song Desafinado: Bossa Nova development and change in the international scene1 Liliana Harb Bollos Universidade Federal de Goiás, Brasil [email protected] Fernando A. de A. Corrêa Faculdade Santa Marcelina, Brasil [email protected] Carlos Henrique Costa Universidade Federal de Goiás, Brasil [email protected] 1. Introduction Considered the “turning point” (Medaglia, 1960, p. 79) in modern popular Brazi- lian music due to the representativeness and importance it reached in the Brazi- lian music scene in the subsequent years, João Gilberto’s LP, Chega de saudade (1959, Odeon, 3073), was released in 1959 and after only a short time received critical and public acclaim. The musicologist Brasil Rocha Brito published an im- portant study on Bossa Nova in 1960 affirming that “never before had a happe- ning in the scope of our popular music scene brought about such an incitement of controversy and polemic” (Brito, 1993, p. 17). Before the Chega de Saudade recording, however, in February of 1958, João Gilberto participated on the LP Can- ção do Amor Demais (Festa, FT 1801), featuring the singer Elizete Cardoso. The recording was considered a sort of presentation recording for Bossa Nova (Bollos, 2010), featuring pieces by Vinicius de Moraes and Antônio Carlos Jobim, including arrangements by Jobim. On the recording, João Gilberto interpreted two tracks on guitar: “Chega de Saudade” (Jobim/Moraes) and “Outra vez” (Jobim). The groove that would symbolize Bossa Nova was recorded for the first time on this LP with ¹ The first version of this article was published in the Anais do V Simpósio Internacional de Musicologia (Bollos, 2015), in which two versions of “Desafinado” were discussed. -

Read Full Article in PDF Version

The Subversive Songs of Bossa Nova: Tom Jobim in the Era of Censorship Irna Priore and Chris Stover OSSA nova flourished in Brazil at the end of the 1950s. This was a time of rapid Bdevelopment and economic prosperity in the country, following President Jucelino Kubitschek’s 1956 proclamation of “fifty years of progress in five,” but after the 1964 coup d’état, when General Humberto Castello Branco’s military regime took control of Brazil, the positive energy of the bossa nova era quickly dissipated.1 Soon after the 1964 coup the atmosphere changed: civil rights were suppressed, political dissent was silenced, and many outspoken singer-songwriters, authors and playwrights, journalists, and academics were censored, arrested, and imprisoned. First-generation bossa nova artists, however, were able to avoid such persecution because their music was generally perceived as apolitical.2 This essay challenges this perception by analyzing the ways in which iconic bossa nova composer Antônio Carlos (“Tom”) Jobim inscribed subversive political thought through musical syntax and lyrical allegory in several of his post-1964 songs. We begin by providing a brief overview of the socio-political history of 1960s Brazil, considering some general features of the Brazilian protest song (canção engajada) before focusing on Chico Buarque’s anthemic “Roda viva” as an exemplar of that style. We then move to a detailed examination of the Jobim compositions “Sabiá” and “Ligia,” the lyrics to both of which speak of love, longing, and saudade in the manner of many bossa nova songs, but within which can be found incisive (if carefully coded) critiques of the Castello Branco government. -

Prohibido Full Score

Jazz Lines Publications Presents the jeffrey sultanof master edition prohibido As recorded by benny carter Arranged by benny carter edited by jeffrey sultanof full score from the original manuscript jlp-8230 Music by Benny Carter © 1967 (Renewed 1995) BEE CEE MUSIC CO. All Rights Reserved Including Public Performance for Profit Used by Permission Layout, Design, and Logos © 2010 HERO ENTERPRISES INC. DBA JAZZ LINES PUBLICATIONS AND EJAZZLINES.COM This Arrangement has been Published with the Authorization of the Estate of Benny Carter. Jazz Lines Publications PO Box 1236 Saratoga Springs NY 12866 USA benny carter series prohibido At long last, Benny Carter’s arrangements for saxophone ensembles are now available, authorized by Hilma Carter and the Benny Carter Estate. Carter himself is one of the legendary soloists and composer/arrangers in the history of American music. Born in 1905, he studied piano with his mother, but wanted to play the trumpet. Saving up to buy one, he realized it was a harder instrument that he’d imagined, so he exchanged it for a C-melody saxophone. By the age of fifteen, he was already playing professionally. Carter was already a veteran of such bands as Earl Hines and Charlie Johnson by his twenties. He became chief arranger of the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra when Don Redman left, and brought an entirely new style to the orchestra which was widely imitated by other arrangers and bands. In 1931, he became the musical director of McKinney’s Cotton Pickers, one of the top bands of the era, and once again picked up the trumpet. -

Chega Saudade

RUY CASTRO CHEGA DE SAUDADE A HISTÓRIA E AS HISTÓRIAS DA BOSSA NOVA Projeto gráfi co Hélio de Almeida 4 ª- edição revista, ampliada e defi nitiva 10224-miolo-chegadesaudade.indd 3 5/30/16 2:23 PM Copyright © 1990 by Ruy Castro Grafia atualizada segundo o Acordo Ortográfico da Língua Portuguesa de 1990, que entrou em vigor no Brasil em 2009. Revisão Isabel Jorge Cury Índice remissivo Luciano Marchiori Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação (cip) (Câmara Brasileira do Livro, sp, Brasil) Castro, Ruy, 1948- Chega de saudade : a história e as histórias da Bossa Nova / Ruy Castro. — 4ª- ed. — São Paulo : Companhia das Letras, 2016. isbn 978-85-359-2752-8 1. Bossa Nova (Música) – Brasil – História e crítica 2. Música popular – Brasil i. Título. 16-03549 cdd-781.630981 Índice para catálogo sistemático: 1. Brasil : Bossa Nova : Música popular : História e crítica 781.630981 [2016] Todos os direitos desta edição reservados à editora schwarcz s.a. Rua Bandeira Paulista, 702, cj. 32 04532-002 — São Paulo — sp Telefone: (11) 3707-3500 Fax: (11) 3707-3501 www.companhiadasletras.com.br www.blogdacompanhia.com.br facebook.com/companhiadasletras instagram.com/companhiadasletras twitter.com/cialetras Em 1960, último show amador da Bossa Nova: João Gilberto na “Noite do amor, do sorriso e da flor” 10224-miolo-chegadesaudade.indd 6 5/30/16 2:23 PM SUMÁRIO Prólogo: Juazeiro, 1948 ...................................................................... 15 PARTE 1: O GRANDE SONHO 1. Os sons que saíam do porão............................................................. 29 2. Tempo quente nas Lojas Murray ..................................................... 45 3. A guerra dos conjuntos vocais ......................................................... 63 4. A montanha, o sol, o mar ................................................................. -

Mixed Folios

mixed folios 447 The Anthology Series – 581 Folk 489 Piano Chord Gold Editions 473 40 Sheet Music Songbooks 757 Ashley Publications Bestsellers 514 Piano Play-Along Series 510 Audition Song Series 444 Freddie the Frog 660 Pop/Rock 540 Beginning Piano Series 544 Gold Series 501 Pro Vocal® Series 448 The Best Ever Series 474 Grammy Awards 490 Reader’s Digest Piano 756 Big Band/Swing Songbooks 446 Recorder Fun! 453 The Big Books of Music 475 Great Songs Series 698 Rhythm & Blues/Soul 526 Blues 445 Halloween 491 Rock Band Camp 528 Blues Play-Along 446 Harmonica Fun! 701 Sacred, Christian & 385 Broadway Mixed Folios 547 I Can Play That! Inspirational 380 Broadway Vocal 586 International/ 534 Schirmer Performance Selections Multicultural Editions 383 Broadway Vocal Scores 477 It’s Easy to Play 569 Score & Sound Masterworks 457 Budget Books 598 Jazz 744 Seasons of Praise 569 CD Sheet Music 609 Jazz Piano Solos Series ® 745 Singalong & Novelty 460 Cheat Sheets 613 Jazz Play-Along Series 513 Sing in the Barbershop 432 Children’s Publications 623 Jewish Quartet 478 The Joy of Series 703 Christian Musician ® 512 Sing with the Choir 530 Classical Collections 521 Keyboard Play-Along Series 352 Songwriter Collections 548 Classical Play-Along 432 Kidsongs Sing-Alongs 746 Standards 541 Classics to Moderns 639 Latin 492 10 For $10 Sheet Music 542 Concert Performer 482 Legendary Series 493 The Ultimate Series 570 Country 483 The Library of… 495 The Ultimate Song 577 Country Music Pages Hall of Fame 643 Love & Wedding 496 Value Songbooks 579 Cowboy Songs -

The Music of Antonio Carlos Jobim

FACULTY ARTIST FACULTY ARTIST SERIES PRESENTS SERIES PRESENTS THE MUSIC OF ANTONIO THE MUSIC OF ANTONIO CARLOS JOBIM (1927-1994) CARLOS JOBIM (1927-1994) Samba Jazz Syndicate Samba Jazz Syndicate Phil DeGreg, piano Phil DeGreg, piano Kim Pensyl, bass Kim Pensyl, bass Rusty Burge, vibraphone Rusty Burge, vibraphone Aaron Jacobs, bass* Aaron Jacobs, bass* John Taylor, drums^ John Taylor, drums^ Monday, February 13, 2012 Monday, February 13, 2012 Robert J. Werner Recital Hall Robert J. Werner Recital Hall 8:00 p.m. 8:00 p.m. *CCM Student *CCM Student ^Guest Artist ^Guest Artist CCM has become an All-Steinway School through the kindness of its donors. CCM has become an All-Steinway School through the kindness of its donors. A generous gift by Patricia A. Corbett in her estate plan has played a key role A generous gift by Patricia A. Corbett in her estate plan has played a key role in making this a reality. in making this a reality. PROGRAMSelections to be chosen from the following: PROGRAMSelections to be chosen from the following: A Felicidade Falando de Amor A Felicidade Falando de Amor Bonita The Girl from Ipanema Bonita The Girl from Ipanema Brigas Nunca Mais One Note Samba Brigas Nunca Mais One Note Samba Caminos Cruzados Photograph Caminos Cruzados Photograph Chega de Saudade So Tinha Se Con Voce Chega de Saudade So Tinha Se Con Voce Corcovado Triste Corcovado Triste Desafinado Wave Desafinado Wave Double Rainbow Zingaro Double Rainbow Zingaro Antonio Carlos Jobim was born in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, to Antonio Carlos Jobim was born in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, to cultured parents. -

Jazz Quartess Songlist Pop, Motown & Blues

JAZZ QUARTESS SONGLIST POP, MOTOWN & BLUES One Hundred Years A Thousand Years Overjoyed Ain't No Mountain High Enough Runaround Ain’t That Peculiar Same Old Song Ain’t Too Proud To Beg Sexual Healing B.B. King Medley Signed, Sealed, Delivered Boogie On Reggae Woman Soul Man Build Me Up Buttercup Stop In The Name Of Love Chasing Cars Stormy Monday Clocks Summer In The City Could It Be I’m Fallin’ In Love? Superstition Cruisin’ Sweet Home Chicago Dancing In The Streets Tears Of A Clown Everlasting Love (This Will Be) Time After Time Get Ready Saturday in the Park Gimme One Reason Signed, Sealed, Delivered Green Onions The Scientist Groovin' Up On The Roof Heard It Through The Grapevine Under The Boardwalk Hey, Bartender The Way You Do The Things You Do Hold On, I'm Coming Viva La Vida How Sweet It Is Waste Hungry Like the Wolf What's Going On? Count on Me When Love Comes To Town Dancing in the Moonlight Workin’ My Way Back To You Every Breath You Take You’re All I Need . Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic You’ve Got a Friend Everything Fire and Rain CONTEMPORARY BALLADS Get Lucky A Simple Song Hey, Soul Sister After All How Sweet It Is All I Do Human Nature All My Life I Believe All In Love Is Fair I Can’t Help It All The Man I Need I Can't Help Myself Always & Forever I Feel Good Amazed I Was Made To Love Her And I Love Her I Saw Her Standing There Baby, Come To Me I Wish Back To One If I Ain’t Got You Beautiful In My Eyes If You Really Love Me Beauty And The Beast I’ll Be Around Because You Love Me I’ll Take You There Betcha By Golly -

Bebopnet: Deep Neural Models for Personalized Jazz Improvisations - Supplementary Material

BEBOPNET: DEEP NEURAL MODELS FOR PERSONALIZED JAZZ IMPROVISATIONS - SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL 1. SUPPLEMENTARY MUSIC SAMPLES We provide a variety of MP3 files of generated solos in: https://shunithaviv.github.io/bebopnet Each sample starts with the melody of the jazz stan- dard, followed by an improvisation whose duration is one chorus. Sections BebopNet in sample and BebopNet out of sample contain solos of Bebop- Net without beam search over chord progressions in and out of the imitation training set, respectively. Section Diversity contains multiple solos over the same stan- Figure 1. Digital CRDI controlled by a user to provide dard to demonstrate the diversity of the model for user- continuous preference feedback. 4. Section Personalized Improvisations con- tain solos following the entire personalization pipeline for the four different users. Section Harmony Guided Improvisations contain solos generated with a har- monic coherence score instead of the user preference score, as described in Section 3.2. Section Pop songs contains solos over the popular non-jazz song. Some of our favorite improvisations by BebopNet are presented in the first sec- Algorithm 1: Score-based beam search tion, Our Favorite Jazz Improvisations. Input: jazz model fθ; score model gφ; batch size b; beam size k; update interval δ; input in τ sequence Xτ = x1··· xτ 2 X 2. METHODS τ+T Output: sequence Xτ+T = x1··· xτ+T 2 X in in in τ×b 2.1 Dataset Details Vb = [Xτ ;Xτ ; :::; Xτ ] 2 X ; | {z } A list of the solos included in our dataset is included in b times scores = [−1; −1; :::; −1] 2 Rb section 4. -

The Norton Jazz Recordings 2 Compact Discs for Use with Jazz: Essential Listening 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE NORTON JAZZ RECORDINGS 2 COMPACT DISCS FOR USE WITH JAZZ: ESSENTIAL LISTENING 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Scott DeVeaux | 9780393118438 | | | | | The Norton Jazz Recordings 2 Compact Discs for Use with Jazz: Essential Listening 1st edition PDF Book A Short History of Jazz. Ships fast. Claude Debussy did have some influence on jazz, for example, on Bix Beiderbecke's piano playing. Miles Davis: E. Retrieved 14 January No recordings by him exist. Subgenres Avant-garde jazz bebop big band chamber jazz cool jazz free jazz gypsy jazz hard bop Latin jazz mainstream jazz modal jazz M-Base neo-bop post-bop progressive jazz soul jazz swing third stream traditional jazz. Special Attributes see all. Like New. Archived from the original on In the mids the white New Orleans composer Louis Moreau Gottschalk adapted slave rhythms and melodies from Cuba and other Caribbean islands into piano salon music. Traditional and Modern Jazz in the s". See also: s in jazz , s in jazz , s in jazz , and s in jazz. Charlie Parker's Re-Boppers. Hoagy Carmichael. Speedy service!. Visions of Jazz: The First Century. Although most often performed in a concert setting rather than church worship setting, this form has many examples. Drumming shifted to a more elusive and explosive style, in which the ride cymbal was used to keep time while the snare and bass drum were used for accents. Season 1. Seller Inventory While for an outside observer, the harmonic innovations in bebop would appear to be inspired by experiences in Western "serious" music, from Claude Debussy to Arnold Schoenberg , such a scheme cannot be sustained by the evidence from a cognitive approach. -

O Imaginêrio De Antonio Carlos Jobim

O IMAGINÁRIO DE ANTONIO CARLOS JOBIM: REPRESENTAÇÕES E DISCURSOS Patrícia Helena Fuentes Lima A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Languages (Portuguese). Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: Advisor: Monica Rector Reader: Teresa Chapa Reader: John Chasteen Reader: Fred Clark Reader: Richard Vernon © 2008 Patrícia Helena Fuentes Lima ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT PATRÍCIA HELENA FUENTES LIMA: Antonio Carlos Jobim: representações e discursos (Under the direction of Monica Rector) My aim with the present work is to describe the personal and creative trajectory of this artist that became known to his audience and people as a hero in the mythological sense—an individual that constructs a series of victories and defeats that continues until death, after which he is glorified by his community. Therefore, I approach the narratives that made him famous: the ones produced by the print press as well as those texts that negotiate meaning, memory, domain and identity created by his fans. I will place special emphasis on the fact that his public produced a definitive narrative about his figure, an account imbued with devotion, familiarity and creativity following his death. More specifically, I identify intertwined relations between the Brazilian audience and the media involved with creating the image of Antonio Carlos Jobim. My hypothesis is that Antonio Carlos Jobim’s image was exhaustively associated with the Brazilian musical movement Bossa Nova for ideological reasons. Specially, during a particular moment in Brazilian history—the Juscelino Kubitschek’s years (1955-1961). -

Swingville Label Discography

Swingville Label Discography: 2000 Series: SVLP 2001 - Coleman Hawkins and The Red Garland Trio - Coleman Hawkins and The Red Garland Trio [1960] It’s a Blue World/I Want to Be Loved/Red Beans/Bean’s Blues/Blues For Ron SVLP 2002 - Tiny In Swingville - Tiny Grimes with Richardson [1960] Annie Laurie/Home Sick/Frankie & Johnnie/Down with It/Ain’t Misbehaving/Durn Tootin’ SVLP 2003 - Tate's Date - Buddy Tate [1960] Me ‘n’ You/Idling/Blow Low/Moon Dog/No Kiddin’/Miss Ruby Jones SVLP 2004 - Callin' the Blues - Tiny Grimes [1960] Reissue of Prestige 7144. Callin’ the Blues/Blue Tiny/Grimes’ Times/Air Mail Special SVLP 2005 – Coleman Hawkins’ All Stars - Coleman Hawkins with Joe Thomas and Vic Dickenson [1960] You Blew Out the Flame/More Bounce to the Vonce/I’m Beginning to See the Light/Cool Blue/Some Stretching SVLP 2006 - The Happy Jazz of Rex Stewart - Rex Stewart [1960] Red Ribbon/If I Could Be with You/Four or Five Times/Rasputin/Please Don’t Talk About me When I’m Gon/San/You Can Depend on Me/I Would Do Most Anything For You/Tell Me/Nagasaki SVLP 2007 - Buck Jumpin' - Al Casey [1960] Buck Jumpin’/Casey’s Blues/Don’t Blame Me/Ain’t Misbehavin’/Honeysuckle Rose/Body & Soul/Rosetta SVLP 2008 - Swingin' with Pee Wee - Pee Wee Russell [1960] What Can I Say Dear/Midnight Blue/Very Thought of You/Lulu’s Back in Town/I Would Do Most Anything For You/Wrap Your Troubles in Dreams/Englewood SVLP 2009 - Yes Indeed! - Claude Hopkins [1960] It Don’t Mean a Thing/Willow Weep For Me/Yes Indeed/Is It So/Empty Bed Blues/What Is This Thing Called Love/Morning Glory SVLP 2010 – Rockin’ in Rhythm - Swingville All Stars (Al Sears, T. -

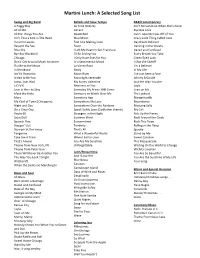

A Selected Song List

Martini Lunch: A Selected Song List Swing and Big Band Ballads and Slow Tempo R&R/Contemporary A Foggy Day As Time Goes By Ain’t No Sunshine When She’s Gone All of Me At Last Bye Bye Love All the Things You Are Bewitched Can’t Take My Eyes Off of You Ain’t That a Kick in The Head Blue Moon Crazy Little Thing Called Love Autumn Leaves Feel Like Making Love Daydream Believer Beyond the Sea Fever Dancing in the Streets Blue Sky I Left My Heart in San Francisco Dazed and Confused Bye Bye Blackbird I’ll Be Seeing You Every Breath You Take Chicago I Only Have Eyes for You Green Eyed Lady Don’t Get Around Much Anymore In a Sentimental Mood I Shot the Sheriff Fly Me to the Moon La Vie en Rose I’m a Believer In the Mood Misty In My Life Isn’t It Romantic Moon River I’ve Just Seen a Face It Had to Be You Moonlight Serenade Johnny B Goode Jump, Jive, Wail My Funny Valentine Just the Way You Are L-O-V-E Nearness of You Layla Love is Here to Stay Someday My Prince Will Come Lean on Me Mack the Knife Someone to Watch Over Me The Luckiest More Sometime Ago Margaritaville My Kind of Town (Chicago is) Somewhere My Love Moondance Night and Day Somewhere Over the Rainbow Mustang Sally On a Clear Day Speak Softly Love (Godfather theme) My Girl Route 66 Strangers in the Night Pick Up the Pieces Satin Doll Summer Wind Rock Around the Clock Spanish Flea Summertime Rock This Town Steppin’ Out Tenderly Rolling in the Deep Stompin’at the Savoy That’s All Spooky Tangerine What a Wonderful World Stand by Me Take the A Train When I Fall in Love Sweet Caroline That’s Amore You Are My Sunshine This Masquerade Theme from New York, NY Unforgettable Waiting On the World to Change Theme from Peter Gun Wichita Lineman There Will Never Be Another You Latin/Bossa Nova You Are So Beautiful The Way You Look Tonight And I Love Her You Are the Sunshine of My Life Witchcraft Blue Bossa Your Song When the Saints Go Marching In Caravan Cantaloupe Island Ethnic and Special Occasion Blues and Soul Days of Wine and Roses Beer Barrel Polka All Blues Desafinado Holidays/Christmas songs .