Breaking the Racial and Poverty Lines Jeffrey C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LGBTIQ+ Health Australia

LGBTIQ+ Health Australia Response to the Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability Issues Paper Executive Summary Question 8 of the Issues Paper on promoting inclusion of the Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability addresses the barriers and challenges to inclusion of LGBTIQ+ people with disability. LGBTIQ+ people with disability experience multi-layered discrimination due to their diverse sexual orientations, gender identity and intersex status. Applying an intersectional lens is fundamental to designing and implementing effective programs to develop more inclusive society for LGBTIQ+ people with disability. LGBTIQ+ Health Australia welcomes the opportunity to respond to the Issues Paper addressing barriers to inclusion of LGBTIQ+ people with disability. The submission highlights evidence-based factors that create exclusive spaces for LGBTIQ+ people with disability, such as lack of feeling of support, psychological distress, violence and harassment against them. It also addresses experience of minority stressors, data collection on LGBTIQ populations with disability, intersectional experiences, the role of self-determined community organisations and the importance of co-design approaches across projects and programs to inclusion of LGBTIQ+ people with disability. Introduction LGBTIQ+ Health Australia (LHA) is the largest national peak organisation working to promote the health and wellbeing of LGBTIQ+ people and communities. LHA is uniquely placed with a diverse membership that spans across states and territories, and includes LGBTIQ+ self-determined community health organisations, LGBTIQ+ community groups and state and territory peak bodies, service providers, researchers, and individuals. LHA is strategically positioned to provide a national focus to improving the health and wellbeing of LGBTIQ+ people through policy, advocacy, representation, research evidence, and capacity building across all health portfolios that are of significance to our communities. -

Compendium of Health Data Sources for Adults with Intellectual Disabilities

2011 Compendium of Health Data Sources for Adults with Intellectual Disabilities Center for Developmental Disabilities Evaluation and Research, Shriver Center, University of Massachusetts Medical School Human Services Research Institute November 2011 Authors: Alexandra Bonardi, Emily Lauer, Courtney Noblett University of Massachusetts Medical School’s Center for Developmental Disabilities Evaluation and Research (CDDER) Sarah Taub, Julie Bershadsky Human Services Research Institute The authors thank Patrick Gleason for his editorial assistance, and members of the RTOI Project Advisory Group for their formative guidance throughout the development of this work. RTOI Project Advisory Group: Robert Baldor, Mary Blauvelt, Val Bradley, Mike Fox, Matt Janicki, Christine Linehan, Chas Moseley, Deirdra Murphy, Susan Parish, Ismaila Ramon, Steven Staugaitis. This compendium was developed as part of the 2010 Research Topic of Interest (RTOI): Health Surveillance of Adults with Intellectual Disability, awarded by the Association of University Centers on Disabilities (AUCD) and funded through a cooperative agreement with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities (NCBDDD). Additional project materials can be accessed by contacting the Principal Investigator at [email protected]. COMPENDIUM OF HEALTH DATA SOURCES FOR ADULTS WITH INTELLECTUAL 2011 DISABILITIES Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................... -

2009-2010 Student Templates Instruction Manual

Nebraska Student and Staff Record System http://www.nde.state.ne.us/nssrs STUDENT Templates Instruction Manual Version 4.2.0 – November 18, 2009 Student Student Snapshot Student Summary Attendance School Enrollment Replaces (all or in part) the following NDE data collections: • NDE02-001 Dropout Report • NDE02-002 Annual Statistical Summary • NDE02-003 Intermediate Education Agency Annual Statistical Summary • NDE02-017 School District Membership • NDE02-043 High School Completer Report • NDE03-018 State Aid Supplement to School District Membership Report • NDE11-005 Limited English Proficient Student Survey • NDE11-009 Emergency Immigrant • NDE16-010 Career and Technical Education Accountability and Annual Report • NDE28-021 Title 1 Free/Reduced Lunch Data Form (Nonpublic) • NDE30-005 Final Count of High Ability Learners 2009-2010 Nebraska Department of Education 301 Centennial Mall South PO Box 94987 Lincoln, NE 68509-4987 888-285-0556 402-471-3151 [email protected] This instruction manual is provided to assist school personnel in submitting data to the Nebraska Department of Education. The information contained herein is intended to be consistent with Rules 10, 14, 21, and 24 and relevant statutes. However, this instruction manual is not a substitute for the actual rules and/or statutes upon which it is based. Please refer to the relevant statutes and/or rules for the actual state requirements and for additional information or clarification. TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................... -

Staff Perceptions of Barriers to Workplace Participation

1 DOING IT DIFFERENTLY STAFF PERCEPTIONS OF THE BARRIERS TO WORKPLACE PARTICIPATION EXPERIENCED BY PUBLIC SERVANTS WITH DISABILITY IN THE AUSTRALIAN PUBLIC SERVICE MARK EVANS, MEREDITH EDWARDS, CARMEL McGREGOR AND PENNEY UPTON 2 November 2016 3 CONTENTS 04 Acknowledgements 05 About the Institute for Governance and Policy Analysis 06 About the Authors 08 Acronyms 09 Prologue: – selected perceptions of people with disability 11 Executive Summary 24 1. Introduction 26 2. What the existing evidence tells us 38 3. Research methods 41 4. Research Findings 62 5. In Conclusion – doing it differently 66 6. References 70 ANNEX A: Recruitment Guide for Focus Groups 71 ANNEX B: Focus Group Schedules 77 ANNEX C: Quantitative Survey Questionnaire 81 ANNEX D: Focus Group Perceptions of the State of Play and the Way Forward LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES Figures 20 Figure ES1: Barriers to workplace participation experienced by people with disability 40 Figure 1: Declared disabilities 63 Figure 2: Barriers to workplace participation experienced by people with disability Tables 39 Table 1: Roles and disability status of respondents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 4 This project forms part of a broader program of research on disability policy in Australia which began in 2014. Members of the Institute for Governance and Policy Analysis (IGPA) at the University of Canberra were con- cerned to build on the gains of the National Disability Insurance Scheme and heighten public awareness of the need for disability policy reform in Australia. A Reference Group consisting of David Brady (Deafness Forum of Australia), Laurie Brown (Professor, IGPA), Meredith Edwards AM (Emeritus Professor IGPA), Mark Evans (Director, IGPA), Josh Fear (Mental Health Australia), Owen Livermore (Australian Public Service Commis- sion), Keith Mahar (Mental Illness Education ACT), Carmel McGregor (Adj. -

2015 Annual Report (PDF)

2014 AnnualReport Center for Disability Rights, Inc. 2015 497 State Street Rochester • NY 14608 (585) 546-7510 PAGE Reflecons 02 from President & CEO Dear friends, 2015 marks a major milestone for the Disability Rights Movement, with the celebraon of the 25th Anniversary of the Americans with Disabilies Act (ADA). Events and celebraons were taking place all across the country throughout the year. During the months of June and July, CDR hosted a series of eleven ADA events free of charge and open to the community to help bring awareness of the ADA for the disability community and to truly celebrate such a momentous anniversary! We completed our celebraon with CDR’s annual Gala fundraiser where we recognized several influenal individuals in the Rochester community and across New York State that have posively impacted the work we do towards full integraon, independence, and civil rights for people with disabilies. The celebraons were a lot of fun for all in aendance, however we did not just spend the year celebrang the work that has been done. In true CDR fashion, our Advocacy team was hard at work draing new legislaon to further the work of the ADA and finally make community living an absolute right for people with disabilies; the Disability Integraon Act. CDR and several advocates in the Disability Rights Movement worked closely with Senator Schumer to create this new legislaon, that builds on the 25 years of work that ADAPT has done to end the instuonal bias and provide seniors and people with disabilies home and community‐based services (HCBS) as an alternave to instuonalizaon. -

Submission 58

National Disability Agreement Review Productivity Commission Locked Bag 2, Collins St East Melbourne VIC 8003 National Disability Agreement review—Productivity Commission Issues Paper The AIHW welcomes the opportunity to provide a submission to the Productivity Commission’s review into the National Disability Agreement. The AIHW has an active role in collecting, analysing and making publicly available information relating to people with disability. Within this context, our submission (attached) highlights the importance of ensuring that a strong evidence base is available to support policy decisions for people with disability. This requires considering the broader system of supports and payments for people with disability and their carers, and taking a strategic, connected approach to developing associated data and reporting requirements. The AIHW is a major national agency producing independent, relevant and reliable health and welfare information and statistics to support better decisions, leading to better health and wellbeing for Australians. We inform policy development and public discussion through data development activities and by producing reports, datasets and other products—adding to the evidence base that is critical to good policy making and effective service delivery. We cover nearly 50 individual health and welfare topics in addition to our compendium flagship publications Australia’s health and Australia’s welfare. We make our data, information and analytical products available widely, in accessible formats, and currently release hundreds of information products annually—including on disability, ageing and aged care, mental health, disease, injury, hospitals, homelessness, housing, child protection, and health and welfare expenditure. We would be very pleased to meet with Commission staff to expand on the matters raised in this submission, as required. -

Annual Report (Right)

ACCESSIBILITY • ADVOCACY • AMERICANS WITH DISABILITIES ACT • BELOVED COMMUNITY • CIVIL RIGHTS • COLLECTIVE ACTION • COMMUNITY • DISABILITY RIGHTS • ECONOMIC EMPOWERMENT • EDUCATION • EMPATHY • EMPLOYMENT • EQUAL OPPORTUNITY • FAMILY • FRIENDSHIP • GRASSROOTS • HUMAN RIGHTS • INCLUSION • INTERDEPENDENCE • LOVE • OLMSTEAD • REAL CAREERS • REAL COMMUNITIES • REAL HOMES • REAL INFLUENCE • REAL LEARNING • REAL SUPPORTS • SOCIAL JUSTICE • VOTING RIGHTS • ACCESSIBILITY • ADVOCACY • AMERICANS WITH DISABILITIES ACT • BELOVED COMMUNITY • CIVIL RIGHTS • COLLECTIVE ACTION • COMMUNITY • DISABILITY RIGHTS • ECONOMIC EMPOWERMENT • EDUCATION • EMPATHY • EMPLOYMENT • EQUAL OPPORTUNITY • FAMILY • FRIENDSHIP • GRASSROOTS • HUMAN RIGHTS • INCLUSION • INTERDEPENDENCE • LOVE • OLMSTEAD • REAL CAREERS • REAL COMMUNITIES • REAL HOMES • REAL INFLUENCE • REAL LEARNING • REAL SUPPORTS • SOCIAL JUSTICE • VOTING RIGHTS • ACCESSIBILITY • ADVOCACY • AMERICANS WITH DISABILITIES ACT • BELOVED COMMUNITY • CIVIL RIGHTS • COLLECTIVE ACTION • COMMUNITY • DISABILITY RIGHTS • ECONOMIC EMPOWERMENT • EDUCATION • EMPATHY • EMPLOYMENT • EQUAL OPPORTUNITY • FAMILY • FRIENDSHIP • GRASSROOTS • HUMAN RIGHTS • INCLUSION • INTERDEPENDENCE • LOVE • OLMSTEAD • REAL CAREERS • REAL COMMUNITIES • REAL HOMES • REAL INFLUENCE • REAL LEARNING • REAL SUPPORTS • SOCIAL JUSTICE • VOTING RIGHTS • ACCESSIBILITY • ADVOCACY • AMERICANS WITH DISABILITIES ACT • BELOVED COMMUNITY • CIVIL RIGHTS • COLLECTIVE ACTION • COMMUNITY • DISABILITY RIGHTS • ECONOMIC EMPOWERMENT • EDUCATION • EMPATHY • EMPLOYMENT -

Disability-Related Questions for Administrative Datasets

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Disability-Related Questions for Administrative Datasets Rosamond H. Madden 1,*, Sue Lukersmith 1,2,*, Qingsheng Zhou 1,3 , Melita Glasgow 4,5 and Scott Johnston 4,6 1 Centre for Disability Research and Policy, Centre for Disability Research and Policy, Sydney School of Health Sciences, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney, Sydney 2006, Australia; [email protected] 2 Research School Population Health, Australian National University, Canberra 2601, Australia 3 Western New South Wales Local Health District, Dubbo 2830, Australia 4 Public Service Commission, New South Wales, Sydney 2001, Australia; [email protected] (M.G.); [email protected] (S.J.) 5 Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, Wellington 6004, New Zealand 6 Revenue NSW, Parramatta 2150, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected] (R.H.M.); [email protected] (S.L.) Received: 27 May 2020; Accepted: 16 July 2020; Published: 28 July 2020 Abstract: High rates of unemployment among people with disability are long-standing and persistent problems worldwide. For public policy,estimates of prevalence and population profiles are required for designing support schemes such as Australia’s National Disability Insurance Scheme; for monitoring implementation of the United Nations Convention on Rights of Persons with Disabilities; and for monitoring service access, participation, and equity for people with disability in mainstream systems including employment. In the public sector, creating a succinct identifier for disability in administrative systems is a key challenge for public policy design and monitoring. This requires concise methods of identifying people with disability within systems, producing data comparable with population data to gauge accessibility and equity. -

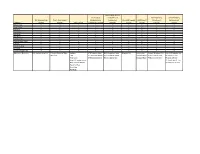

Elements Fall Membership Dataset Dec 1 Child Count Dataset Test

Annual High School CTE Program Graduates and Postsecondary Postsecondary Fall Membership Dec 1 Child Count Graduates and Completers Annual Dropouts OGR Cohort Enrollment Achievement Elements Dataset Dataset Test Dataset Completers Dataset Dataset Dataset Dataset Dataset Dataset School Year Level Code Div Num Div Name Sch Num Sch Name Grade Code Federal Race Code Gender Disability Flag LEP Flag Disadvantaged Flag Additional Elements Fall Membership Cnt Primary Disability Type Subject CTE Program Num HS Completion Num Dropout Cnt Cohort Cnt Cohort Graduate Cnt Cohort Graduate Cnt Dec1 Cnt Test CTE Program Name HS Completer Name Diploma Rate PS Institution Type PS Credit DE Cnt Test Level CTE Completer Cnt HS Completer Cnt Dropout Rate PS Enrollment Cnt PS Unkn DE Cnt Avg SOL Scaled Score PS Credit wo DE Cnt Pass Advanced Rate PS Unkn wo DE Cnt Pass Prof Rate Pass Rate Fail Rate Dataset Description VDOE annually collects statistics on the number of students enrolled in public school on September 30. This report, known as Fall Membership, is submitted by each school in Virginia that officially enrolls students (student records are maintained on a Virginia teacher's register or automated system). Fall Membership Data are collected at the student-level and are limited to one active record per student within the state. Aggregated totals reflect an Dataset unduplicated head count of all public school students. Suppression Rules: Membership totals for groups based on grade, gender and/or race are included in the data regardless of how many students are in the group. Any group filtered on economically disadvantaged status, Limited English Proficiency status and/or disability status with fewer than 10 students is not included in the data. -

SVA Perspectives: Disability

SVA Perspectives: Disability Plain English version November 2019 Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................... 2 SVA’s vision – having a say ............................................. 3 Steps to better outcomes ............................................... 5 The issue ........................................................................ 6 SVA insights ................................................................. 11 Understanding what works ........................................... 12 1. Making sure people with disability are heard ........ 12 2. People with disability: inclusion and access ......... 14 3. People with disability have the right to choose the specialist services and supports that are best for them ......................................................... 24 Better intel .................................................................... 33 1 SVA PERSPECTIVES: DISABILITY Introduction Social Ventures Australia (SVA) is working towards an Australia where everyone is leading a fulfilling life. While there has been some great work done, one in four people in Australia experience disadvantage. SVA is committed to finding solutions and bringing about change. Since 2002, we have developed an understanding of what it takes to tackle disadvantage. In 2016 SVA released a series of Perspective Papers on education, employment, housing and the things that improve the lives of First Australian people and communities. We have used these insights to focus on two new areas: -

The Disability and Wellbeing Monitoring Framework and Indicators: Technical Report

THE DISABILITY AND WELLBEING MONITORING FRAMEWORK AND INDICATORS: TECHNICAL REPORT in partnership with Acknowledgements Thanks to the members of the Expert Panel of Advice who provided invaluable input into the development of the monitoring framework and indicators, and to the NSW Council for Intellectual Disability for hosting a facilitated focus group as part of the consultation process. The authors are grateful for feedback provided by the Centre of Research Excellence in Disability and Health (CRE-DH) Partner Advisory Group and members of the wider CRE-DH research team. Thanks also to Laura Davy who developed easy-read versions of the consultation materials. Authors Nicola Fortune1, Hannah Badland2, Shane Clifton1, Eric Emerson3, Jerome Rachele4, Roger J Stancliffe1, Qingsheng Zhou1 and Gwynnyth Llewellyn1 1. Centre for Disability Research and Policy, The University of Sydney 2. Centre for Urban Research, RMIT University 3. Centre for Disability Research, Lancaster University 4. Disability and Health Unit, Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, The University of Melbourne All of the authors are affiliated with the Centre of Research Excellence in Disability and Health. ISBN 978 0 7340 5577 4 Suggested citation Fortune N, Badland H, Clifton S, Emerson E, Rachele J, Stancliffe RJ, Zhou Q & Llewellyn G (2020). The Disability and Wellbeing Monitoring Framework and Indicators: Technical report. Centre of Research Excellence in Disability and Health, Melbourne. Contact information Centre of Research Excellence in Disability and Health (CRE-DH) Telephone +61 3 8344 0717 Email [email protected] Website www.credh.org.au Twitter @DisabilityHlth 2 CRE-DH | Disability and Wellbeing Monitoring Framework and Indicators CONTENTS Executive Summary 5 1. -

Health and Disability System Review – Final Report – Pūrongo Whakamutunga

HEALTH AND DISABILITY SYSTEM REVIEW | AROTAKE PŪNAHA HAUORA, WHAIKAHA HOKI Published March 2020 by the Health and Disability System Review. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. In essence, you are free to copy, distribute and adapt the work, as long as you attribute the work to the Crown (Health and Disability Sector Review, New Zealand) and abide by the other licence terms. To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Attribution should be in written form and not by reproduction of any such emblem, logo, or Coat of Arms. Liability While all care and diligence has been used in processing, analysing, and extracting data and information in this publication, the Health and Disability System Review gives no warranty it is error free and will not be liable for any loss or damage suffered by the use directly, or indirectly, of the information in this publication. ISBN print: 978-0-473-52333-6 ISBN online: 978-0-473-51856-1 Citation: Health and Disability System Review. 2020. Health and Disability System Review – Final Report – Pūrongo Whakamutunga. Wellington: HDSR. This report is available from www.systemreview.health.govt.nz/final-report PAGE | ii FINAL REPORT | PŪRONGO WHAKAMUTUNGA Whakataukī E kore e taea te whenu kotahi ki te raranga i te whāriki kia mōhio tātou ki ā tātou. Mā te mahi tahi ō ngā whenu, mā te mahi tahi ō ngā kairaranga, ka oti tenei whāriki. I te otinga me titiro tātou ki ngā mea pai ka puta mai.