The Absence of Plurality in Sri Lankan Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learning English Our Way: a Unique Strategy

Monday 5th April, 2010 9 Learning English our way: A unique strategy nal, with this little anec- Colonial Government, was com- stuck when it came to ‘About learning English Our Way. dote. This story was told to manded in English. How they Turn’. As you know, even edu- Another point. The other day, us trainee Police could hope to inspire local foot cated people are bemused ini- I read in your ‘World View’ Probationers in 1964 at soldiers to fight to save their tially by these movements, till pages that Lee Quan Yew, that the Police Training King’s empire by issuing com- they get used to it. One could visionary leader of Singapore College by one of mand in an alien language, is imagine how confusing it would who earlier advocated that all our Drill another matter. But that is how be to village folk to whom even Singaporeans should learn Bernard Shaw Instructors. it was. The British started to the concept of ‘right’ and ‘left’ English for many reasons These Drill recruit Ceylonese to their mili- was of little meaning in their including avoiding the catastro- Instructors, tary, when the WW II broke out. practical life. To them, the idea phe that befell Sri Lanka, is now English though they Many village lads turned up to of ‘About Turn’ would have been advising the Singapore Chinese are very join the Milteriya then, not so simply incomprehensible. community to start talking to without airs strict, and much for the love of the British Try as they might, the drill their children in Mandarin, as uncompro- Empire, but mainly to see the instructors failed to drive home Chinese was going to be the lan- n The Island of 27th mising on world at State expense. -

The Melodies of Sunil Santai

THE MELODIES OF SUNIL SANTAI The object of this paper is to attempt an aesthetic appreciation of the melodies of Sunil Santa (1915-1981), the great composer who was one of the pioneers of modern music in Sri Lanka. 2 After a brief outline of the historical background, I propose to touch on the relation of the melodies to the language and poetry of their lyrics, the impact of various musical traditions, including folk-song, and their salient features. I. Sources and Historical Background Among the sources for a study of Sunil Santa's music, first in importance are the songs themselves. Most of these were published by the composer in book form with music notation, and all these have been reprinted by Mrs. Sunil Santa, who has also brought out posthumously four collections of works which remained largely unprinted during the composer's lifetime. The music is generally in Sinhala letter format, but there are two collections in staff notation,' to which must be added the first two books of Christian lyrics by Fr. Moses Perera which include a number of Sunil Santa's melodies. 4 Many of these songs were recorded for broadcast either by the composer himself or by other singers who were his pupils or associates. Unfortunately, these recordings have not been preserved properly and are rarely heard nowadays. However, the S.L.B.C. has issued one LP, one EP\ and two cassettes of his songs," and a third cassette, Guvan I. This paper was read before the Royal Asiatic Society (Sri Lanka Branch) on 31st January 1994, and is now published with a few emendations. -

LAND of TRIUMPH 21-23 Siri Daru Heladiva Purathane Ananda Samarakoon 13.01.1916-05.04.1962

C ONTENTS Page 1. SRI LANKA - LAND OF TRIUMPH 21-23 Siri Daru Heladiva Purathane Ananda Samarakoon 13.01.1916-05.04.1962 2. A CHRISTMAS SONG 24 Seenu Handin Lowa Pibidenava Rev. Father Mercelene Jayakody 3. IN THIS WORLD 25 Ira Ilanda Payana Loke. Sri Chandraratnc Manawasinghe 19.06.1913-04.10.1964 4. LIFE IS A FLOWING RIVER 26 Galana Gangaki Jeevithe Sri Chandraratne Manawasinghe 5. HUSH BABY 27 Sudata Sude Walakulai Arisen Ahubudu 6. BEHOLD, SWEETHEART 28 Anna Sudo Ara Pata Wala Herbert M Senevirathne 24.04.1923-07.06.1987 7. A NIGHT SO MILD 29 Me Saumya Rathriya Herbert M Seneviratne 11 8. SPRING FLOWERS 30 Vasanthaye Mai Pokuru Mahagama Sekara 07.04.1924-14.01.1976 9. LONELY BLUE SKY 31 Palu Anduru Nil Ahasa Mamai Mahagama Sekara 10. THE JOURNEY IS NEVER ENDING 32 Gamana Nonimei Lokaye Mahagama Sekara 11. VILLAGE BLOSSOM 33 Hade Susuman Dalton Alwis 07.12.1926-01.08.1987 12. PEERING THROUGH THE WINDOW 34 Kaurudo Ara Kauluwen Dalton Alwis 13. BEAUTIFUL REAPERS 35 Daathata Walalu C.DeS.Kulathilake-14.12.1926-22.11.2005 14. JOY 36 Shantha Me Ra Yame W. D. Amaradeva 15. SERENADE OF THE HEART 37 Mindada Hee Sara Madawala S Rathnayake 05.12.1929-09.01.1997 12 16. I'M A FERRYMAN 38 Oruwaka Pawena Karunaratne Abeysekara 03.06.1930-20.04.1983 17. WORLD OF TRANSIENCE 39 Chanchala Anduru Lowe Karunaratne Abeysekara 18. THE GO BETWEEN 40 Enna Mandanale Karunarathne Abesekara 19. SINGLE GIRL 41 Awanhale. Karunaratne Abeysekara 20. INFINITY. 42 Anantha Vu Derana Sara Sugathapala Senerath Yapa 21. -

An Overview About Different Sources of Popular Sinhala Songs

AN OVERVIEW ABOUT DIFFERENT SOURCES OF POPULAR SINHALA SONGS Nishadi Meddegoda Abstract Music is considered to be one of the most complex among the fine arts. Although various scholars have given different opinions about the origin of music, the historical perspectives reveal that this art, made by mankind on account of various social needs and occasions, has gradually developed along with every community. It is a well-known fact that any fine art, whether it is painting, sculpture, dance or music, is interrelated with communal life and its history starts with society. Art is forever changing and that change comes along with the change in those societies. This paper looks into the different sources of contemporary popular Sinhala songs without implying a strict border between Sinhala and non-Sinhala beyond the language used. Sources, created throughout history, deliver not only a steady stream of ideas. They are also often converted into labels and icons for specific features within a given society. The consideration of popularity as an economic reasoning and popularity as an aesthetic pattern makes it possible to look at the different important sources using multiple perspectives and initiating a wider discussion that overcomes narrow national definitions. It delivers an overview which should not be taken as an absolute repertoire of sources but as an open pathway for further explorations. Keywords Popular song, Sinhala culture, Nurthi, Nadagam, Sarala Gee INTRODUCTION Previous studies of music have revealed that first serious discussions and analyses of music emerged in Sri Lanka with the focus on so-called tribal tunes. The tunes of tribes who lived in stone caves of Sri Lanka have got special attention of scholars worldwide since they were believed of being some of the few “unchanged original” tunes. -

Wartime Romance

3 Wartime Romance Chapters 1 and 2 center on songwriters and poets who participated in Sri Lankan movements that sought to politicize religion and language as symbols of Sri Lankan or Sinhalese identity. Sinhalese songwriters and poets fashioned their projects in relation or opposition to Western or Indian cultural influence. In this chapter I demonstrate that identity politics suddenly grew faint during World War II. Dur- ing the war songwriters and poets grew weary of didacticism pertaining to religion and linguistic identity. Amid rapidly growing publishing and music industries, they turned toward romanticism to entertain the public. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Sri Lankans feared the Japanese would also bomb the British naval bases in Colombo.1 Daily sirens announced citywide rehearsals to prepare for a similar strike. Protective bomb shelters and trenches were created throughout Colombo in case of an attack. The government ordered residents to place black paper over lamps in the evening to prevent enemy ships from locating heavily populated areas of the city. Three months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese navy launched the Easter Sunday Raid, an air attack against the British naval bases in Sri Lanka. They bombed Colombo and killed thirty-seven Sri Lankan civilians. In September the British armed forces transformed a variety of Sri Lankan institutions into military bases. The Royal Air Force used the radio station as their base, and the armed forces took over schools, such as S. Thomas’ College in Mount Lavinia, Colombo. The city became populated with soldiers from England, France, and India.2 Given Sri Lanka’s political alignment with the Allied powers and the arrival of Allied forces to Colombo from England, France, and India, it is not a coinci- dence that the new forms of Sinhala song and poetry, what I am calling “wartime 56 Wartime Romance 57 romance,” were indebted to works by famous English, French, and Indian poets and novelists. -

Western Music

Western Music Grade - 13 Teacher’s Instructional Manual (This syllabus would be implemented from 2010) Department of Aesthetic Education National Institute of Education Maharagama FOREWORD Curriculum developers of the NIE were able to introduce Competency Based Learning and Teaching curricula for grades 6 and 10 in 2007 and were also able to extend it to 7,8 and 11 progressively every year and even to GCE (A/L) classes in 2009. In the same manner syllabi and Teacher's Instructional Manuals for grades 12 and 13 for different subjects with competencies and competency levels that should be developed in students are presented descriptively. Information given on each subject will immensely help the teachers to prepare for the Learning - Teaching situations. I would like to mention that curriculum developers have followed a different approach when preparing Teacher's Instructional Manuals for Advanced Level subjects when compared to the approaches they followed in preparing Junior Secondary and Senior Secondary curricula. (Grades 10,11) In grades 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11 teachers were oriented to a given format as to how they should handel the subject matter in the Learning - Teaching process, but in designing AL syllabi and Teacher's Instructional Manuals freedom is given to the teachres to work as they wish. At this level we expect teachers to use a suitable learning method form the suggested learning methods given in the Teacher's Instructional Manuals to develop competencies and competency levels relevant to each lesson or lesson unit. Whatever the trarning approach the teacher uses it should be done effectively and satisfactorily to realize the expected competencies and competency levels. -

The Regional Nationalism of Rapiyel Tennakoon's Bat Language and Sunil Santa's "Song for the Mother Tongue"

Commonalities of Creative Resistance Commonalities of Creative Resistance: The Regional Nationalism of Rapiyel Tennakoon's Bat Language and Sunil Santa's "Song for the Mother Tongue" Abstract This article highlights commonalities of regional nationalism between the poetry and song of two Hela Havula (The Pure Sinhala Fraternity) members: Rapiyel Tennakoon and Sunil Santha. I reveal how their creative works advocated indigenous empowerment in opposition to Indian cultural hegemony, and against state solicitations for foreign consultation about Sinhala language planning and Sinhalese music development. Tennakoon challenged the negative portrayal of Sri Lankan characters in the Indian epic, the Ramayana, and Santa fashioned a Sri Lankan form of song that could stand autonomous from Indian musical influence. Tennakoon lashed out against the Sinhala-language dictionary office's hire of German professor Wilhelm Geiger as consultant, and Santa quit Radio Ceylon in 1953 when the station appealed to Professor S.N. Ratanjankar, from North India, for advice on designing a national form of Sri Lankan music. Such dissent betrays an effort to define the nation not in relation to the West, but to explicitly position it in relation to India. A study of Tennekoon's and Santa's careers and compositions supplement the many works that focus on how native elite in South Asia fashioned a modern national culture in relation to the West, with an awareness of the regional nationalist, non-elite communities—who also had a stake in defining the nation— that were struggling against inter-South Asian cultural hegemony. Keywords: Regional nationalism; Sinhala poetry; Sinhala music; Linguistic politics; Song text; Modernist reforms. -

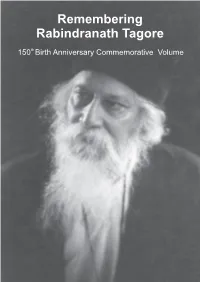

Remembering Rabindranath Tagore Volume

Remembering Rabindranath Tagore 150th Birth Anniversary Commemorative Volume Compiled and edited by Sandagomi Coperahewa University of Colombo High Commission of India, Colombo Indian Cultural Centre, Colombo India-Sri Lanka Foundation, Colombo University of Colombo Cover Portrait of Tagore taken while he was in Sri Lanka in 1934. Courtesy : Rabindra Bhavana, Santiniketan. Views expressed in the articles are those of the contributors and not necessarily of the High Commission of India, the Indian Cultural Centre and the University of Colombo. Published by University of Colombo 2011 Printer Softwave Printing & Packaging (Pvt) Ltd. 107 D, Havelock Road, Colombo 05. Contents Message from His Excellency the President of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka Message from His Excellency the High Commissioner of India Message from the Vice Chancellor, University of Colombo Introduction Page 1. Tagore and Sri Lanka: The Highlights of an Abiding Relationship 01 K.N.O. Dharmadasa 2. “ The Inside Story” : Gender and Modernity in Chokher Bali 08 Radha Chakaravarty 3. A South Asian Alter-realism: Tagore's Art of Short Story (in Sinhala) 15 Liyanage Amarakeerti 4. The Musical Journey of Rabindranath Tagore 32 Reba Som 5. An Insight into the Impact of Rabindranath Tagore on Sinhala Art 39 and Music Sunil Ariyaratne 6. Bengali Renaissance, Tagore and Sri Lanka (in Sinhala) 48 Chintaka Ranasinghe 7. Nationalism and National Freedom: Tagore’s Perspective 71 Nirosha Paranavitana 8. Modern Sinhala Literary Arts Discourse and 81 Rabindranath Tagore (in Sinhala) Sarath Wijesooriya 9. Philosophy of Humanistic Universalism of Rabindranath Tagore 91 (in Tamil) Mallika Rajaratnam 10. Educational Thoughts of Tagore (in Sinhala) 97 Piyal Somaratne 11. -

Parliamentary Election 2020

N.B. - ThisI Extraordinary fldgi ( ^I& GazettefPoh -is YS%printed ,xld in m%cd;dka;s%l Sinhala, Tamil iudcjd§ and English ckrcfha Languages w;s separately. úfYI .eiÜ m;%h - 2020'06'09 1 A PART I : SEC. (I) - GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA - 09.06.2020 Y%S ,xld m%cd;dka;%sl iudcjd§ ckrcfha .eiÜ m;%h w;s úfYI The Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka EXTRAORDINARY wxl 2179$7 - 2020 cqks ui 09 jeks w`.yrejdod - 2020'06'09 No. 2179/7 - TUESDAY, JUNE 09, 2020 (Published by Authority) PART I : SECTION (I) — GENERAL Government Notifications THE PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS ACT, No. 1 OF 1981 Notice Under Section 24(1) (b) and (d) GENERAL ELECTIONS OF MEMBERS OF THE PARLIAMENT WITH REFERENCE TO THE NOTICE NO. 2167/12 DATED 20.03.2020 ISSUED BY THE ELECTION COMMISSION NOTICE is hereby given under Section 24(1) (b) and (d) of the Parliamentary Elections Act, No. 1 of 1981 that – (I) the order in which the name of each recognized Political Party and the distinguishing number of each Independent Group and the symbol allotted to each such Party or Group appearing in the ballot paper of each such Electoral District shall be in the same order as given in the Schedule hereto ; and the names of candidates (as indicated by the candidates) of each recognized Political Party or Independent Group, placed in alphabetical order in accordance with the Sinhala alphabet, nominated for election as Members of Parliament from each such Electoral District and the preferential number assigned to each candidate, are as specified in the Schedule hereto ; (II) the situation of the polling station or stations for each of the polling districts in each such Electoral District, and the particular polling stations reserved for female voters, if any, are as specified in the Schedule hereto. -

A Knowledge Structure in the Form of a Classification Scheme for Sinhala Music to Store in a Domain Specific Digital Library

A Knowledge Structure in the Form of a Classification Scheme for Sinhala Music to Store in a Domain Specific Digital Library BY S.P. Ratnayake (2009/MISM/29) Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of MASTERS I IFORMATIO SYSTEMS MAAGEMET At the UIVERSITY OF COLOMBO SUPERVISOR: Mrs. S. C. Jayasuriya December 2011 1 DECLARATION I certify that this Dissertation does not incorporate without acknowledgement any material previously submitted for the Degree or Diploma in any University, and to the best of my knowledge and belief it does not contain any material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made in the text Date ……………………. ………………………………………… S. P. Ratnayake The undersigned, have supervised the dissertation entitled A knowledge structure in the form of a classification scheme for Sinhala music to store in a domain specific digital librar y presented by S. P. Ratnayake, a candidate for the degree of Masters in Information Systems Management, and hereby certify that, in my opinion, it is worthy of submission for examination. Date: …………………….. …………………………………… S. C. Jayasuriya Supervisor 2 Table of contents Page i. Declaration i ii. List of Figures vi iii. List of Tables vii iv. Acknowledgements x v. Abbreviations xii 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Background of the study 1 1.2 Significance of the study 3 1.3 Problem statement 4 1.4 Objectives 5 1.5 Limitations 6 1.6 Methodology 6 2. Literature review 8 2.1 Literature review of the evolution of Sinhala music in Sri Lanka 8 2.1.1 Pre-Historic period 8 2.1.2 Ancient History 8 2.1.3 Medieval History 11 2.1.4 Modern History 16 2.1.5 British Colonial Period 31 2.1.6 Main attributes of Sinhala Music 39 2.2 Literature review of the digital libraries and related technologies 55 2.2.1 Digital music libraries implemented in the world 55 3 2.2.2 The influences of Client Server technologies to implement digital music libraries 57 2.2.3 Organization, classification and information retrieval techniques in libraries 58 3. -

Revisiting Rabindranath Tagore's Legacy

Revisiting Rabindranath Tagore’s Legacy Revisiting Rabindranath Tagore’s Legacy Revisiting Rabindranath Tagore’s Legacy Based on the Proceedings of the International Seminar held on 4 August 2016 at the University of Colombo, Sri Lanka to mark the 75th Death Anniversary of Rabindranath Tagore Edited by Sandagomi Coperahewa Centre for Contemporary Indian Studies (CCIS) University of Colombo, Sri Lanka Indian Cultural Centre, Colombo Revisiting Rabindranath Tagore’s Legacy Edited by Sandagomi Coperahewa Editorial assistance: Chaturika Karunanayake © Centre for Contemporary Indian Studies | Indian Cultural Centre, Colombo, 2014 All Rights Reserved ISBN - Views expressed in the articles are those of the contributors and not necessarily of the Centre for Contemporary Indian Studies (CCIS) or Indian Cultural Centre. Published by Indian Cultural Centre. Colombo, Sri Lanka Tel/Fax: Printed and bound in Sri Lanka by ……………………….. Contents Remarks by His Excellency Y.K. Sinha, High Commissioner of India Remarks by Senior Professor Lakshman Dissanayake, Vice Chancellor | University of Colombo Introduction by Professor Sandagomi Coperahewa, Director | CCIS 1. Rabindranath Tagore’s Legacy Seventy-five Years after his Demise Martin Kämpchen 2. Bridges of Culture: Performing Shapmochan ( The Redemption) Amrit Sen 3. A Very Modern Tagore Madhubhashini Disanayaka Ratnayaka 4. Towards a Clearer Understanding of the Impact of Tagore’s Legacy in Sri Lanka Susil Sirivardana 5. De – Anglicizing Tagore Daya Dissanayaka Remarks by His Excellency Y.K. Sinha, Former High Commissioner of India Senior Professor Lakshman Dissanayake - Vice Chancellor, Dr. Martin Kämpchen – today’s keynote speaker, Prof. Amrit Sen and other eminent speakers of the academic panel, Prof. Nayani Melegoda, Dean |FGS, Professor Sandagomi Coperahewa, Director |CCIS, Ms.