A Knowledge Structure in the Form of a Classification Scheme for Sinhala Music to Store in a Domain Specific Digital Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learning English Our Way: a Unique Strategy

Monday 5th April, 2010 9 Learning English our way: A unique strategy nal, with this little anec- Colonial Government, was com- stuck when it came to ‘About learning English Our Way. dote. This story was told to manded in English. How they Turn’. As you know, even edu- Another point. The other day, us trainee Police could hope to inspire local foot cated people are bemused ini- I read in your ‘World View’ Probationers in 1964 at soldiers to fight to save their tially by these movements, till pages that Lee Quan Yew, that the Police Training King’s empire by issuing com- they get used to it. One could visionary leader of Singapore College by one of mand in an alien language, is imagine how confusing it would who earlier advocated that all our Drill another matter. But that is how be to village folk to whom even Singaporeans should learn Bernard Shaw Instructors. it was. The British started to the concept of ‘right’ and ‘left’ English for many reasons These Drill recruit Ceylonese to their mili- was of little meaning in their including avoiding the catastro- Instructors, tary, when the WW II broke out. practical life. To them, the idea phe that befell Sri Lanka, is now English though they Many village lads turned up to of ‘About Turn’ would have been advising the Singapore Chinese are very join the Milteriya then, not so simply incomprehensible. community to start talking to without airs strict, and much for the love of the British Try as they might, the drill their children in Mandarin, as uncompro- Empire, but mainly to see the instructors failed to drive home Chinese was going to be the lan- n The Island of 27th mising on world at State expense. -

Download the PDF File

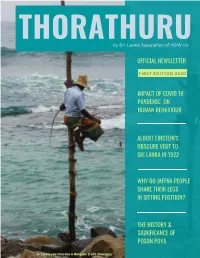

THORATHURUby Sri Lanka Association of NSW Inc OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER FIRST EDITION 2020 IMPACT OF COVID 19 PANDEMIC ON HUMAN BEHAVIOUR ALBERT EINSTEIN’S OBSCURE VISIT TO SRI LANKA IN 1922 WHY DO JAFFNA PEOPLE SHAKE THEIR LEGS IN SITTING POSITION? THE HISTORY & SIGNIFICANCE OF POSON POYA Sri Lankan pole fishermen in Midigama Credit: @woolgarz Let us acknowledge the traditional owners of this land where we are across NSW and pay our respect to elders past and present. The land and their culture have over 65 thousand years’ history and today with more than 270 multicultural nations enriching this land. PAGE 1 EDITOR'S MESSAGE 1 PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE 2 EDITOR'S MESSAGE DINESH RANASINGHE COMMITTEE 2020 4 [email protected] HIGHLIGHTS OF FIRST HALF “Life imposes things on you that you can’t control, OF YEAR ACTIVITIES 5 but you still have the choice of how you’re going to EVENTS live through this." Sri Lankan Flag Raising Ceremony 7 - Celine Dion Young Achiever 9 Senior Luncheon 15 It is indeed a great honour to A huge thank you to all the be the Editor for Thorathuru people who contributed ARTICLES and it is an immense writing the wonderful and pleasure to launch this first inspiring articles, without Impact of Covid 19 Pandemic edition for 2020. which there wouldn’t have on Human Behaviour 16 been this newsletter issue. In this issue, we will recount Cow’s MILK Considered a the various projects and Last but not least, I would like Holy Drink 23 activities in which SLANSW to thank SLANSW President, members were actively Nalika Padmasena, and The History and Significance of involved. -

44Th Convocation University of Sri Jayewardenepura

44th Convocation University of Sri Jayewardenepura Gamhewa Manage Pesala Madhushani Gamage Wijayalathpura Dewage Poornimala Madushani FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Hansani Nisansala Gamage Madugodage Dinusha Madushani AND SOCIAL SCIENCES Meepe Gamage Chathurika Hansamali Gamage Peduru Hewa Harshika Madushani Panawenna Ranadewage Thayomi Dulanji Gansala Amaraweera Wikkrama Gunawardana Lasuni Madushika Liyanagamage Gayan Diyadawa Gamage Niluka Maduwanthi Parana Palliyage Thisara Gayathri Herath Mudiyanselage Shanika Maduwanthi Kongala Hettiarachchige Koshila Gimhani Hewa Rahinduwage Ruwani Maduwanthi Kalubowila Appuhamilage Nipuni Wirajika Gunarathna Sikuradhi Pathige Irosha Maduwanthi Aluth Gedara Champika Prabodani Gunathilaka Wijesekara Gunawardhana Gurusinha Arachchige Maheshika Ahangama Vithanage Maheshika Gunathilaka Dissanayake Mudiyanselage Nadeeka Malkanthi Mestiyage Dona Nihari Manuprabhashani Gunathilaka Hewa Uluwaduge Nadeesha Manamperi Withana Arachchillage Gaya Thejani Gunathilaka Gunasingha Mudiyanselage Rashika Manel Ayodya Lakmali Guniyangoda Widana Gamage Shermila Dilhani Manike Nisansala Sandamali Gurusingha Koonange Mihiri Kanchana Mendis Kariyawasam Bovithanthri Prabodha Hansaji Nikamuni Samadhi Nisansala Mendis Kanaththage Supuni Hansika Warnakulasooriya Wadumesthrige Nadeesha Chathurangi Ranagalage Pawani Hansika Mendis Gama Athige Harshani Morapitiyage Madhuka Dhananjani Morapitiya Rambukkanage Kaushalya Hasanthi Munasinghe Mudiyanselage Uthpala Madushani Munasinghe Henagamage Piyumi Nisansala Henagamage Ella Deniyage Upeksha -

The Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka Wxl 2"165 – 2020 Fmnrjdß Ui 28 Jeks Isl=Rdod – 2020'02'28 No

YS% ,xld m%cd;dka;s%l iudcjd§ ckrcfha .eiÜ m;%h The Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka wxl 2"165 – 2020 fmnrjdß ui 28 jeks isl=rdod – 2020'02'28 No. 2,165 – fRiDAy, fEBRuARy 28, 2020 (Published by Authority) PART I : SECTION (I) – GENERAL (Separate paging is given to each language of every Part in order that it may be filed separately) PAGE PAGE Proclamations, &c., by the President … — Government Notifications … … 220 Appointments, &c., by the President … 196 Price Control Orders … … — Appointments, &c., by the Cabinet of Ministers … 196 Central Bank of Sri Lanka Notices… … — Appointments, &c., by the Public Service Commission — Accounts of the Government of Sri Lanka … — Revenue and Expenditure Returns… … — Appointments, &c., by the Judicial Service Commission — Miscellaneous Departmental Notices … 250 Other Appointments, &c. … … 197 Notice to Mariners … … — Appointments, &c., of Registrars … — “Excise Ordinance” Notices … … — IMportant NOTICE REGARDING Acceptance OF NOTICES FOR PUBlication IN THE WEEKLY “GAZETTE” AttENtiON is drawn to the Notification appearing in the 1st week of every month, regarding the latest dates and times of acceptance of Notices for publication in the weekly Gazettes, at the end of every weekly Gazette of Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. All notices to be published in the weekly Gazettes shall close at 12.00 noon of each friday, two weeks before the date of publication. All Government Departments, Corporations, Boards, etc. are hereby advised that Notifications fixing closing dates and times of applications in respect of Post-Vacancies, Examinations, tender Notices and dates and times of Auction Sales, etc. should be prepared by giving adequate time both from the date of despatch of notices to Govt. -

Silence in Sri Lankan Cinema from 1990 to 2010

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Director of Copyright Services sydney.edu.au/copyright SILENCE IN SRI LANKAN CINEMA FROM 1990 TO 2010 S.L. Priyantha Fonseka FACULTY OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES THE UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy at the University of Sydney 2014 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor material previously published or written by another person nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma of a university or other institute of higher learning, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. -

The Melodies of Sunil Santai

THE MELODIES OF SUNIL SANTAI The object of this paper is to attempt an aesthetic appreciation of the melodies of Sunil Santa (1915-1981), the great composer who was one of the pioneers of modern music in Sri Lanka. 2 After a brief outline of the historical background, I propose to touch on the relation of the melodies to the language and poetry of their lyrics, the impact of various musical traditions, including folk-song, and their salient features. I. Sources and Historical Background Among the sources for a study of Sunil Santa's music, first in importance are the songs themselves. Most of these were published by the composer in book form with music notation, and all these have been reprinted by Mrs. Sunil Santa, who has also brought out posthumously four collections of works which remained largely unprinted during the composer's lifetime. The music is generally in Sinhala letter format, but there are two collections in staff notation,' to which must be added the first two books of Christian lyrics by Fr. Moses Perera which include a number of Sunil Santa's melodies. 4 Many of these songs were recorded for broadcast either by the composer himself or by other singers who were his pupils or associates. Unfortunately, these recordings have not been preserved properly and are rarely heard nowadays. However, the S.L.B.C. has issued one LP, one EP\ and two cassettes of his songs," and a third cassette, Guvan I. This paper was read before the Royal Asiatic Society (Sri Lanka Branch) on 31st January 1994, and is now published with a few emendations. -

LAND of TRIUMPH 21-23 Siri Daru Heladiva Purathane Ananda Samarakoon 13.01.1916-05.04.1962

C ONTENTS Page 1. SRI LANKA - LAND OF TRIUMPH 21-23 Siri Daru Heladiva Purathane Ananda Samarakoon 13.01.1916-05.04.1962 2. A CHRISTMAS SONG 24 Seenu Handin Lowa Pibidenava Rev. Father Mercelene Jayakody 3. IN THIS WORLD 25 Ira Ilanda Payana Loke. Sri Chandraratnc Manawasinghe 19.06.1913-04.10.1964 4. LIFE IS A FLOWING RIVER 26 Galana Gangaki Jeevithe Sri Chandraratne Manawasinghe 5. HUSH BABY 27 Sudata Sude Walakulai Arisen Ahubudu 6. BEHOLD, SWEETHEART 28 Anna Sudo Ara Pata Wala Herbert M Senevirathne 24.04.1923-07.06.1987 7. A NIGHT SO MILD 29 Me Saumya Rathriya Herbert M Seneviratne 11 8. SPRING FLOWERS 30 Vasanthaye Mai Pokuru Mahagama Sekara 07.04.1924-14.01.1976 9. LONELY BLUE SKY 31 Palu Anduru Nil Ahasa Mamai Mahagama Sekara 10. THE JOURNEY IS NEVER ENDING 32 Gamana Nonimei Lokaye Mahagama Sekara 11. VILLAGE BLOSSOM 33 Hade Susuman Dalton Alwis 07.12.1926-01.08.1987 12. PEERING THROUGH THE WINDOW 34 Kaurudo Ara Kauluwen Dalton Alwis 13. BEAUTIFUL REAPERS 35 Daathata Walalu C.DeS.Kulathilake-14.12.1926-22.11.2005 14. JOY 36 Shantha Me Ra Yame W. D. Amaradeva 15. SERENADE OF THE HEART 37 Mindada Hee Sara Madawala S Rathnayake 05.12.1929-09.01.1997 12 16. I'M A FERRYMAN 38 Oruwaka Pawena Karunaratne Abeysekara 03.06.1930-20.04.1983 17. WORLD OF TRANSIENCE 39 Chanchala Anduru Lowe Karunaratne Abeysekara 18. THE GO BETWEEN 40 Enna Mandanale Karunarathne Abesekara 19. SINGLE GIRL 41 Awanhale. Karunaratne Abeysekara 20. INFINITY. 42 Anantha Vu Derana Sara Sugathapala Senerath Yapa 21. -

An Overview About Different Sources of Popular Sinhala Songs

AN OVERVIEW ABOUT DIFFERENT SOURCES OF POPULAR SINHALA SONGS Nishadi Meddegoda Abstract Music is considered to be one of the most complex among the fine arts. Although various scholars have given different opinions about the origin of music, the historical perspectives reveal that this art, made by mankind on account of various social needs and occasions, has gradually developed along with every community. It is a well-known fact that any fine art, whether it is painting, sculpture, dance or music, is interrelated with communal life and its history starts with society. Art is forever changing and that change comes along with the change in those societies. This paper looks into the different sources of contemporary popular Sinhala songs without implying a strict border between Sinhala and non-Sinhala beyond the language used. Sources, created throughout history, deliver not only a steady stream of ideas. They are also often converted into labels and icons for specific features within a given society. The consideration of popularity as an economic reasoning and popularity as an aesthetic pattern makes it possible to look at the different important sources using multiple perspectives and initiating a wider discussion that overcomes narrow national definitions. It delivers an overview which should not be taken as an absolute repertoire of sources but as an open pathway for further explorations. Keywords Popular song, Sinhala culture, Nurthi, Nadagam, Sarala Gee INTRODUCTION Previous studies of music have revealed that first serious discussions and analyses of music emerged in Sri Lanka with the focus on so-called tribal tunes. The tunes of tribes who lived in stone caves of Sri Lanka have got special attention of scholars worldwide since they were believed of being some of the few “unchanged original” tunes. -

A Lecture by Prof Raj Somadeva Be Screened on October 24 Oct the Dramatist Singing

DN page 16 EVENTS MONDAY, OCTOBER 22, 2012 Five dramas to be staged at Punchi theatre ‘Muhunu … oct Thunak’ (Three short plays) direct- 22 ed by Tharin- du, Tharaka Windtalkers and Athauda, ‘Madyawedi- yekuge Asipatha’ directed Windtalkers (2002) will by Namel Weeramuni, be screened on October 23 ‘Sinidu Kirilli’ directed by at 6pm at the American Buddhika Damayantha, Centre, No 44, Galle Road, ‘Ekadhipathi’ directed by Colombo 3. (Running SARASHI SAMARASINGHE Dharmasiri Bandaranayake Time: 134 minutes) and ‘Nattukkari’ directed Having earned Holly- This week’s `Cultural Diary’ brings you details about several other by Namel Weeramuni will ‘Sinidu Kirilli’ and ‘Eka- staged at 6.45 pm. Namel wood’s respect with block- fascinating events happening in the city. Take your pick of stage be staged on October 22, dhipathi’ will be staged at Weeramuni’s script of busters like Face/Off and plays, exhibitions or dance performance and add colour to your 23, 25, 26 and 28 at the 3.30 pm and 6.45 pm ‘Madyawediyekuge Asipa- Mission: Impossible 2, routine life. You can make merry and enjoy the adventures or sit Namel Malini Punchi thea- respectively while tha’ too will be launched at Hong Kong action master back, relax and enjoy a movie of your choice. Make a little space tre, Borella. ‘Madyawediyekuge Asipa- 4.30 pm besides the perfor- John Woo lends his signa- to kick into high gear amid the busy work schedules to enjoy the ‘Muhunu Thunak,’ tha’ and ‘Nattukkari’ will be mance. ture style to serious World exciting events happening at venues around the city. -

Tourist Drivers / Assistants Who Obtained the Covid-19 Tourism

Tourist Drivers / Assistants who Obtained the Covid-19 Tourism Operational Guidelines Awareness and Knowledge under the Supervision of Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority Published by Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority Serial No. Name. Category Contact Number 1 SLTDA/CAS/1427 W.Prabagaran Tourist Driver O77 6 676 338 2 SLTDA/CAS/2308 G.H.Janaka Saman Tourist Driver 0785 947 538 3 SLTDA/CAS/2053 S D Gamini Senarath Tourist Driver 078 9 568 862 4 SLTDA/CAS/1296 S.M.J.N.Suriyagoda Tourist Driver 078 8 882 727 5 SLTDA/CAS/2482 Weerasingha Arachchige Ranesh Lakmal Tourist Driver 078 8 765 392 6 SLTDA/CAS/2498 W.K.S.Fernando Tourist Driver 078 8 015 003 7 SLTDA/CAS/2395 M.P.champika Janadara Van Driver 078 7 064 026 8 SLTDA/CAS/1615 R.M.C.T.Ratnayake Tourist Driver 078 7 050 777 9 SLTDA/CAS/3387 M.F.M.Ruhaib Tourist Driver 078 6 432 303 10 SLTDA/CAS/2256 S.V.L Senavirathna. Tourist Driver 078 6 293 632 11 SLTDA/CAS/2655 W.W.Prasanna Pathmakumara Mendis Tourist Driver 078 5 701 701 12 SLTDA/CAS/3247 Mohamed Riyas Tourist Driver 078 5 628 648 13 SLTDA/CAS/2667 Ross Pereira Tourist Driver 078 5 624 327 14 SLTDA/CAS/3038 P.P.E.Wijayaweera Tourist Driver 078 5 365 827 15 SLTDA/CAS/2010 Anthonidura Prasal Nilujpriya De Silva Tourist Driver 078 5 014 088 16 SLTDA/CAS/2798 A.W.R.S.D.M.R. Upali Baminiwatta Tourist Driver 078 4 977 373 17 SLTDA/CAS/2169 D.V.Dewin De Silva Tourist Driver 078 4 451396 18 SLTDA/CAS/1125 R.P.S.Priyantha Tourist Driver 078 3 565 371 19 SLTDA/CAS/1382 B.G.S.Jayatissa Tourist Driver 078 1 784 651 20 SLTDA/CAS/3141 -

Wartime Romance

3 Wartime Romance Chapters 1 and 2 center on songwriters and poets who participated in Sri Lankan movements that sought to politicize religion and language as symbols of Sri Lankan or Sinhalese identity. Sinhalese songwriters and poets fashioned their projects in relation or opposition to Western or Indian cultural influence. In this chapter I demonstrate that identity politics suddenly grew faint during World War II. Dur- ing the war songwriters and poets grew weary of didacticism pertaining to religion and linguistic identity. Amid rapidly growing publishing and music industries, they turned toward romanticism to entertain the public. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Sri Lankans feared the Japanese would also bomb the British naval bases in Colombo.1 Daily sirens announced citywide rehearsals to prepare for a similar strike. Protective bomb shelters and trenches were created throughout Colombo in case of an attack. The government ordered residents to place black paper over lamps in the evening to prevent enemy ships from locating heavily populated areas of the city. Three months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese navy launched the Easter Sunday Raid, an air attack against the British naval bases in Sri Lanka. They bombed Colombo and killed thirty-seven Sri Lankan civilians. In September the British armed forces transformed a variety of Sri Lankan institutions into military bases. The Royal Air Force used the radio station as their base, and the armed forces took over schools, such as S. Thomas’ College in Mount Lavinia, Colombo. The city became populated with soldiers from England, France, and India.2 Given Sri Lanka’s political alignment with the Allied powers and the arrival of Allied forces to Colombo from England, France, and India, it is not a coinci- dence that the new forms of Sinhala song and poetry, what I am calling “wartime 56 Wartime Romance 57 romance,” were indebted to works by famous English, French, and Indian poets and novelists. -

Rukmani Devi and Her Talents Groups Within the Agricultural Sector Should Be Introduced

The Island Opinion Saturday 29th October, 2011 9 Potgul Statue Water scarcity - reply in Seeduwa eply to Siri Gunasinghe’s ’m writing this to report to you of a ‘Interpreting problem that has risen due to an R the Past: A look Iincreased number of illicit water back at the Potgul pumping plants in Seeduwa and sur- Statue’, The Island rounding areas. As a result of this exer- 26 and 27 October. cise the ground water availability has The only way of reduced to dangerous levels leaving the Don’t ruin identifying an area residents in a very bad predica- ancient religious ment. statue is by a con- Our hometown is Seeduwa, which is a sideration of its highly residential area very close to the he audio visual media in the Parakrama ings of thousands of school chil- iconographic attrib- Katunayake Airport and the Export utes, which are Processing Zone. Over the past few recent past highlighted some dren and spectators. How disap- detailed in texts to years a large number of illegal busi- Tdistressing and depressing pointing it would have been for the enable devotees to recognize them. nesses that extract water for industrial happennings over the thoughtless spectators to see the game being I have (Digging into the Past, 2005), washing plants and other various pur- actions of some individuals abusing Samudra disrupted for several hours and given reasons why Siri Gunasinghe’s poses through high-powered pumps have authority. One TV channel showed then being abandoned. (1958) rejection of the statue having sprung up like mushroom. They dig people who are earning their liveli- In the wake of such unexpected alienate farmers and fishermen.