An Overview About Different Sources of Popular Sinhala Songs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learning English Our Way: a Unique Strategy

Monday 5th April, 2010 9 Learning English our way: A unique strategy nal, with this little anec- Colonial Government, was com- stuck when it came to ‘About learning English Our Way. dote. This story was told to manded in English. How they Turn’. As you know, even edu- Another point. The other day, us trainee Police could hope to inspire local foot cated people are bemused ini- I read in your ‘World View’ Probationers in 1964 at soldiers to fight to save their tially by these movements, till pages that Lee Quan Yew, that the Police Training King’s empire by issuing com- they get used to it. One could visionary leader of Singapore College by one of mand in an alien language, is imagine how confusing it would who earlier advocated that all our Drill another matter. But that is how be to village folk to whom even Singaporeans should learn Bernard Shaw Instructors. it was. The British started to the concept of ‘right’ and ‘left’ English for many reasons These Drill recruit Ceylonese to their mili- was of little meaning in their including avoiding the catastro- Instructors, tary, when the WW II broke out. practical life. To them, the idea phe that befell Sri Lanka, is now English though they Many village lads turned up to of ‘About Turn’ would have been advising the Singapore Chinese are very join the Milteriya then, not so simply incomprehensible. community to start talking to without airs strict, and much for the love of the British Try as they might, the drill their children in Mandarin, as uncompro- Empire, but mainly to see the instructors failed to drive home Chinese was going to be the lan- n The Island of 27th mising on world at State expense. -

44Th Convocation University of Sri Jayewardenepura

44th Convocation University of Sri Jayewardenepura Gamhewa Manage Pesala Madhushani Gamage Wijayalathpura Dewage Poornimala Madushani FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Hansani Nisansala Gamage Madugodage Dinusha Madushani AND SOCIAL SCIENCES Meepe Gamage Chathurika Hansamali Gamage Peduru Hewa Harshika Madushani Panawenna Ranadewage Thayomi Dulanji Gansala Amaraweera Wikkrama Gunawardana Lasuni Madushika Liyanagamage Gayan Diyadawa Gamage Niluka Maduwanthi Parana Palliyage Thisara Gayathri Herath Mudiyanselage Shanika Maduwanthi Kongala Hettiarachchige Koshila Gimhani Hewa Rahinduwage Ruwani Maduwanthi Kalubowila Appuhamilage Nipuni Wirajika Gunarathna Sikuradhi Pathige Irosha Maduwanthi Aluth Gedara Champika Prabodani Gunathilaka Wijesekara Gunawardhana Gurusinha Arachchige Maheshika Ahangama Vithanage Maheshika Gunathilaka Dissanayake Mudiyanselage Nadeeka Malkanthi Mestiyage Dona Nihari Manuprabhashani Gunathilaka Hewa Uluwaduge Nadeesha Manamperi Withana Arachchillage Gaya Thejani Gunathilaka Gunasingha Mudiyanselage Rashika Manel Ayodya Lakmali Guniyangoda Widana Gamage Shermila Dilhani Manike Nisansala Sandamali Gurusingha Koonange Mihiri Kanchana Mendis Kariyawasam Bovithanthri Prabodha Hansaji Nikamuni Samadhi Nisansala Mendis Kanaththage Supuni Hansika Warnakulasooriya Wadumesthrige Nadeesha Chathurangi Ranagalage Pawani Hansika Mendis Gama Athige Harshani Morapitiyage Madhuka Dhananjani Morapitiya Rambukkanage Kaushalya Hasanthi Munasinghe Mudiyanselage Uthpala Madushani Munasinghe Henagamage Piyumi Nisansala Henagamage Ella Deniyage Upeksha -

YS% ,Xld M%Cd;Dka;S%L Iudcjd§ Ckrcfha .Eiü M;%H the Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka

YS% ,xld m%cd;dka;s%l iudcjd§ ckrcfha .eiÜ m;%h The Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka wxl 1"991 – 2016 Tlaf;dan¾ ui 28 jeks isl=rdod – 2016'10'28 No. 1,991 – fRiDAy, OCtOBER 28, 2016 (Published by Authority) PART I : SECTION (I) – GENERAL (Separate paging is given to each language of every Part in order that it may be filed separately) PAGE PAGE Proclamations, &c., by the President … — Government Notifications … … 1204 Appointments, &c., by the President … 1128 Price Control Orders … … — Appointments, &c., by the Cabinet of Ministers … — Central Bank of Sri Lanka Notices… … — Accounts of the Government of Sri Lanka … — Appointments, &c., by the Public Service Commission — Revenue and Expenditure Returns… … — Appointments, &c., by the Judicial Service Commission — Miscellaneous Departmental Notices … 1206 Other Appointments, &c. … … 1192 Notice to Mariners … … — Appointments, &c., of Registrars … — “Excise Ordinance” Notices … … — Note.– (i) Code of Criminal Procedure (Amendment) Bill was published as a supplement to the part ii of the Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka of August 12, 2016. (ii) Nation Building tax (Amendment) Bill was published as a supplement to the part ii of the Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka of August 19, 2016. (iii) Land (Restrictions on Alienation) (Amendment) Bill was published as a supplement to the part ii of the Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka of September 02, 2016. IMportant NOTICE REGARDING Acceptance OF NOTICES FOR PUBlication IN THE WEEKLY “GAZETTE” AttENtiON is drawn to the Notification appearing in the 1st week of every month, regarding the latest dates and times of acceptance of Notices for publication in the weekly Gazettes, at the end of every weekly Gazette of Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. -

Packed with Recommendations and the Full List of 2500+ Channels

PACKED WITH RECOMMENDATIONS AND THE FULL LIST OF 2500+ CHANNELS Voted World’s Best Infl ight Entertainment for the Digital Widescreen | December 2017 13th consecutive year! Meet your match in ATOMIC BLONDE and more sizzling action thrillers NEW MOVIES | DOCUMENTARIES | SPORT | ARABIC MOVIES | COMEDY TV | KIDS | BOLLYWOOD | DRAMA | NEW MUSIC | BOX SETS | AND MORE OBCOFCDec17EX2.indd 51 09/11/2017 15:13 EMIRATES ICE_EX2_DIGITAL_WIDESCREEN_62_DECEMBER17 051_FRONT COVER_V1 200X250 44 An extraordinary ENTERTAINMENT experience... Wherever you’re going, whatever your mood, you’ll find over 2500 channels of the world’s best inflight entertainment to explore on today’s flight. THE LATEST Information… Communication… Entertainment… Track the progress of your Stay connected with in-seat* phone, Experience Emirates’ award- MOVIES flight, keep up with news SMS and email, plus Wi-Fi and mobile winning selection of movies, you can’t miss movies and other useful features. roaming on select flights. TV, music and games. from page 16 527 ...AT YOUR FINGERTIPS STAY CONNECTED 4 Connect to the 1500 OnAir Wi-Fi network on all A380s and most Boeing 777s 1 Choose a channel Go straight to your chosen programme by typing the channel WATCH LIVE TV 2 3 number into your handset, or use the onscreen channel entry pad Live news and sport channels are available on 1 3 Swipe left and Search for Move around most fl ights. Find out right like a tablet. movies, TV using the games more on page 9. Tap the arrows shows, music controller pad onscreen to and system on your handset scroll features and select using the green game 2 4 Create and Tap Settings to button 4 access your own adjust volume playlist using and brightness Favourites Home Again Many movies are 113 available in up to eight languages. -

Silence in Sri Lankan Cinema from 1990 to 2010

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Director of Copyright Services sydney.edu.au/copyright SILENCE IN SRI LANKAN CINEMA FROM 1990 TO 2010 S.L. Priyantha Fonseka FACULTY OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES THE UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy at the University of Sydney 2014 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor material previously published or written by another person nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma of a university or other institute of higher learning, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. -

POPULAR LIST 1.ABA RUK SAVANALLY 2.Adara Madura

POPULAR LIST 1.ABA RUK SAVANALLY 2.Adara Madura Athethay 3.ADARA MAL PAVANE 5.AIY NAVEY 6.ANNA SUDO 7.Anndha Sagaray 8.Asoka mal mala 9.BILDA NALAVAY 10.CHANDRMEY RA PAYA 11.DANNA PRIYE 12.DASA RIDANAVA 13.DILEEPA PODI PUTHU 14.DINAKA ME NADI 15.DURA KATHANAKIN 16.EDA RAA 17.Egodath Megodath 18.GAGAVAY MAHA MHUDA 19.GIYAKIN KESY 20.Hethay Irsha Hanga 21.JEVANYE MEE VANYE 22.Kakiri Palena 23.KAL;AK AVAMAN 24.KALAK THISSE 25.KESYE KIYANADA 26.KIMADA NAVAY 27.KIMADA SUMI HIRIYE 28.Kodi Ga Yata 29.MA ITHIN YANNA 30.MABALA KALLE 31.MAGE SUDU MAME 32.MAL BARA HIMDIRIYE 33.Mal Hegena 34.MANA MALI 35.MAVINDA VADANAVA 36.May Mayi Gaha 37.May Mayi Gaha 38.MEE PIRUNU 39.MEE VADAYAKI 40.MEEDUM GALA KANNDE 41.MHA DANATHI VANA BABARA 42.MHUDU RALLA OSSE 43.MINI KINKINI 44.MULADI BANDA 45.OBA MASATHU VAYY 46.OBA NIDANNA 47.PAYA AIY HINAHANNE 48.PIYAMHI PANI BOTHI 49.RA THRAKA OO 50.RUVAN PURAYA 51.SADA MODU VALA 52.SADA VATA RAN THRU 53.SADAY THARUY 54.SADE SADUN 55.SAEREY PIPASEY 56.SHINA LOVE 57.Shinen Oba Mata 58.SODURU LOVATA 59.SUDU PATA MHIDUM 60.SULAGE PAVEE 61.SULAN KURULLO 62.Sulan Ralla Say 63.SURAGANA VASA VALA 64.SURAGANA VASA VALA KAROKE FROM DVD'S 1.ADARA MAL PAWEENE 2.ADHA WEYI IRUDENA 3.AHA NEELA WARAL PERALA 4.AWASARA NATHA MATA-R 5.DASA WEEDHALA 6.DAWASAK THEEWAVI 7.DENEKA RAN SALU PALANDHA 8.DHASAK MAL PIPELHA 9.DOLOS MAHE PAHANA 10.DONA KATHIREENA 11.DOTIN DOTHI 12.EGODA GODAY MAL 13.ELA DOLHA PERUNA 14.ERA PAYA 15.ETHA EPITA AKASAY 16.GEVEETHE PRITHI SANSARAY 17.GEYA KIYA DAMALA 18.HADAPATULAY 19.HANDANA EPHA DAN 20.HANIKA YAMAN -

Nimal Dunuhinga - Poems

Poetry Series nimal dunuhinga - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive nimal dunuhinga(19, April,1951) I was a Seafarer for 15 years, presently wife & myself are residing in the USA and seek a political asylum. I have two daughters, the eldest lives in Austalia and the youngest reside in Massachusettes with her husband and grand son Siluna.I am a free lance of all I must indebted to for opening the gates to this global stage of poets. Finally, I must thank them all, my beloved wife Manel, daughters Tharindu & Thilini, son-in-laws Kelum & Chinthaka, my loving brother Lalith who taught me to read & write and lot of things about the fading the loved ones supply me ingredients to enrich this life's bitter-cake.I am not a scholar, just a sailor, but I learned few things from the last I found Man is not belongs to anybody, any race or to any religion, an independant-nondescript heaviest burden who carries is the Brain. Conclusion, I guess most of my poems, the concepts based on the essence of Buddhist personal belief is the Buddha who was the greatest poet on this planet earth.I always grateful and admire him. My humble regards to all the readers. www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 * I Was Born By The River My scholar friend keeps his late Grandma's diary And a certain page was highlighted in the color of yellow. My old ferryman you never realized that how I deeply loved you? Since in the cradle the word 'depth' I heard several occasions from my parents. -

The Melodies of Sunil Santai

THE MELODIES OF SUNIL SANTAI The object of this paper is to attempt an aesthetic appreciation of the melodies of Sunil Santa (1915-1981), the great composer who was one of the pioneers of modern music in Sri Lanka. 2 After a brief outline of the historical background, I propose to touch on the relation of the melodies to the language and poetry of their lyrics, the impact of various musical traditions, including folk-song, and their salient features. I. Sources and Historical Background Among the sources for a study of Sunil Santa's music, first in importance are the songs themselves. Most of these were published by the composer in book form with music notation, and all these have been reprinted by Mrs. Sunil Santa, who has also brought out posthumously four collections of works which remained largely unprinted during the composer's lifetime. The music is generally in Sinhala letter format, but there are two collections in staff notation,' to which must be added the first two books of Christian lyrics by Fr. Moses Perera which include a number of Sunil Santa's melodies. 4 Many of these songs were recorded for broadcast either by the composer himself or by other singers who were his pupils or associates. Unfortunately, these recordings have not been preserved properly and are rarely heard nowadays. However, the S.L.B.C. has issued one LP, one EP\ and two cassettes of his songs," and a third cassette, Guvan I. This paper was read before the Royal Asiatic Society (Sri Lanka Branch) on 31st January 1994, and is now published with a few emendations. -

Symphony Orchestra of Sri Lanka Westlife

With Chamikara Weerasinghe IN TUNE SATURDAY,SEPTEMBER 5,2009 DN Symphony Orchestra of Sri Lanka presents Classics in Harmony today Abeysekera said about music fans and oriental the concert on being asked classical music fans. ” about the the concert Victor Ratnayaka will whether it be a fusion of sing a set of six songs at Western classical music the Classics in harmony and oriental music, it will concert. Unlike in Western not be a concert of fusion classical music , North of the two great traditions. Indian classical music “ In order to produce recognise voice to be pre- fusion, the two styles have dominant to fashion a Rag. to be blended to produce a According to Sangeeth different sound,” he Ratnakara by Pandit Sar- explained and added ,” nagadeva, music is defined Classics in Harmony will as the combination of vocal stand to complement the President, Sri Lankan Sym- music, instrumental music phony Orchestra, Prof. Ajith two music traditions rather and dance. Nanda Malini Abeysekera than creating “fusion”. It Even without Dance and will preserve the orchestral ern classical music fans to classical music and vice Instrumental music , vocal color of both Western and appreciate Western classi- versa. Singers like Victor music alone can be called Eastern traditions ,” he cal music,” he said. Ratnayaka, Nanda Malini, music. A performer said. ”We do not want to “The concert will ‘not’ W.D.Amaradewa and T.M, should not forget that create a monstrous hybrid be a pop show and the Jayaratna are high caliber voice is predominant in the as such by fusing the two,” experience will be be total- vocalists. -

LAND of TRIUMPH 21-23 Siri Daru Heladiva Purathane Ananda Samarakoon 13.01.1916-05.04.1962

C ONTENTS Page 1. SRI LANKA - LAND OF TRIUMPH 21-23 Siri Daru Heladiva Purathane Ananda Samarakoon 13.01.1916-05.04.1962 2. A CHRISTMAS SONG 24 Seenu Handin Lowa Pibidenava Rev. Father Mercelene Jayakody 3. IN THIS WORLD 25 Ira Ilanda Payana Loke. Sri Chandraratnc Manawasinghe 19.06.1913-04.10.1964 4. LIFE IS A FLOWING RIVER 26 Galana Gangaki Jeevithe Sri Chandraratne Manawasinghe 5. HUSH BABY 27 Sudata Sude Walakulai Arisen Ahubudu 6. BEHOLD, SWEETHEART 28 Anna Sudo Ara Pata Wala Herbert M Senevirathne 24.04.1923-07.06.1987 7. A NIGHT SO MILD 29 Me Saumya Rathriya Herbert M Seneviratne 11 8. SPRING FLOWERS 30 Vasanthaye Mai Pokuru Mahagama Sekara 07.04.1924-14.01.1976 9. LONELY BLUE SKY 31 Palu Anduru Nil Ahasa Mamai Mahagama Sekara 10. THE JOURNEY IS NEVER ENDING 32 Gamana Nonimei Lokaye Mahagama Sekara 11. VILLAGE BLOSSOM 33 Hade Susuman Dalton Alwis 07.12.1926-01.08.1987 12. PEERING THROUGH THE WINDOW 34 Kaurudo Ara Kauluwen Dalton Alwis 13. BEAUTIFUL REAPERS 35 Daathata Walalu C.DeS.Kulathilake-14.12.1926-22.11.2005 14. JOY 36 Shantha Me Ra Yame W. D. Amaradeva 15. SERENADE OF THE HEART 37 Mindada Hee Sara Madawala S Rathnayake 05.12.1929-09.01.1997 12 16. I'M A FERRYMAN 38 Oruwaka Pawena Karunaratne Abeysekara 03.06.1930-20.04.1983 17. WORLD OF TRANSIENCE 39 Chanchala Anduru Lowe Karunaratne Abeysekara 18. THE GO BETWEEN 40 Enna Mandanale Karunarathne Abesekara 19. SINGLE GIRL 41 Awanhale. Karunaratne Abeysekara 20. INFINITY. 42 Anantha Vu Derana Sara Sugathapala Senerath Yapa 21. -

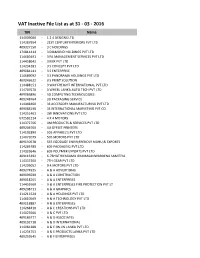

VAT Inactive File List As at 31

VAT Inactive File List as at 31 - 03 - 2016 TIN Name 134009080 - 1 2 4 DESIGNS LTD 114287954 - 21ST CENTURY INTERIORS PVT LTD 409327150 - 3 C HOLDINGS 174814414 - 3 DIAMOND HOLDINGS PVT LTD 114689491 - 3 FA MANAGEMENT SERVICES PVT LTD 114458643 - 3 MIX PVT LTD 114234281 - 3 S CONCEPT PVT LTD 409084141 - 3 S ENTERPRISE 114689092 - 3 S PANORAMA HOLDINGS PVT LTD 409243622 - 3 S PRINT SOLUTION 114488151 - 3 WAY FREIGHT INTERNATIONAL PVT LTD 114707570 - 3 WHEEL LANKA AUTO TECH PVT LTD 409086896 - 3D COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES 409248764 - 3D PACKAGING SERVICE 114448460 - 3S ACCESSORY MANUFACTURING PVT LTD 409088198 - 3S INTERNATIONAL MARKETING PVT CO 114251461 - 3W INNOVATIONS PVT LTD 672581214 - 4 X 4 MOTORS 114372706 - 4M PRODUCTS & SERVICES PVT LTD 409206760 - 4U OFFSET PRINTERS 114102890 - 505 APPAREL'S PVT LTD 114072079 - 505 MOTORS PVT LTD 409150578 - 555 EGODAGE ENVIR;FRENDLY MANU;& EXPORTS 114265780 - 609 PACKAGING PVT LTD 114333646 - 609 POLYMER EXPORTS PVT LTD 409115292 - 6-7BHATHIYAGAMA GRAMASANWARDENA SAMITIYA 114337200 - 7TH GEAR PVT LTD 114205052 - 9.4.MOTORS PVT LTD 409274935 - A & A ADVERTISING 409096590 - A & A CONSTRUCTION 409018165 - A & A ENTERPRISES 114456560 - A & A ENTERPRISES FIRE PROTECTION PVT LT 409208711 - A & A GRAPHICS 114211524 - A & A HOLDINGS PVT LTD 114610569 - A & A TECHNOLOGY PVT LTD 409118887 - A & B ENTERPRISES 114268410 - A & C CREATIONS PVT LTD 114023566 - A & C PVT LTD 409186777 - A & D ASSOCIATES 409192718 - A & D INTERNATIONAL 114081388 - A & E JIN JIN LANKA PVT LTD 114234753 - A & E PRODUCTS LANKA PVT -

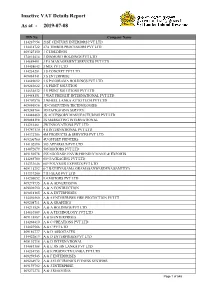

Inactive VAT Details Report As at - 2019-07-08

Inactive VAT Details Report As at - 2019-07-08 TIN No Company Name 114287954 21ST CENTURY INTERIORS PVT LTD 114418722 27A TIMBER PROCESSORS PVT LTD 409327150 3 C HOLDINGS 174814414 3 DIAMOND HOLDINGS PVT LTD 114689491 3 FA MANAGEMENT SERVICES PVT LTD 114458643 3 MIX PVT LTD 114234281 3 S CONCEPT PVT LTD 409084141 3 S ENTERPRISE 114689092 3 S PANORAMA HOLDINGS PVT LTD 409243622 3 S PRINT SOLUTION 114634832 3 S PRINT SOLUTIONS PVT LTD 114488151 3 WAY FREIGHT INTERNATIONAL PVT LTD 114707570 3 WHEEL LANKA AUTO TECH PVT LTD 409086896 3D COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES 409248764 3D PACKAGING SERVICE 114448460 3S ACCESSORY MANUFACTURING PVT LTD 409088198 3S MARKETING INTERNATIONAL 114251461 3W INNOVATIONS PVT LTD 114747130 4 S INTERNATIONAL PVT LTD 114372706 4M PRODUCTS & SERVICES PVT LTD 409206760 4U OFFSET PRINTERS 114102890 505 APPAREL'S PVT LTD 114072079 505 MOTORS PVT LTD 409150578 555 EGODAGE ENVIR;FRENDLY MANU;& EXPORTS 114265780 609 PACKAGING PVT LTD 114333646 609 POLYMER EXPORTS PVT LTD 409115292 6-7 BATHIYAGAMA GRAMASANWARDENA SAMITIYA 114337200 7TH GEAR PVT LTD 114205052 9.4.MOTORS PVT LTD 409274935 A & A ADVERTISING 409096590 A & A CONTRUCTION 409018165 A & A ENTERPRISES 114456560 A & A ENTERPRISES FIRE PROTECTION PVT LT 409208711 A & A GRAPHICS 114211524 A & A HOLDINGS PVT LTD 114610569 A & A TECHNOLOGY PVT LTD 409118887 A & B ENTERPRISES 114268410 A & C CREATIONS PVT LTD 114023566 A & C PVT LTD 409186777 A & D ASSOCIATES 114422819 A & D ENTERPRISES PVT LTD 409192718 A & D INTERNATIONAL 114081388 A & E JIN JIN LANKA PVT LTD 114234753 A &