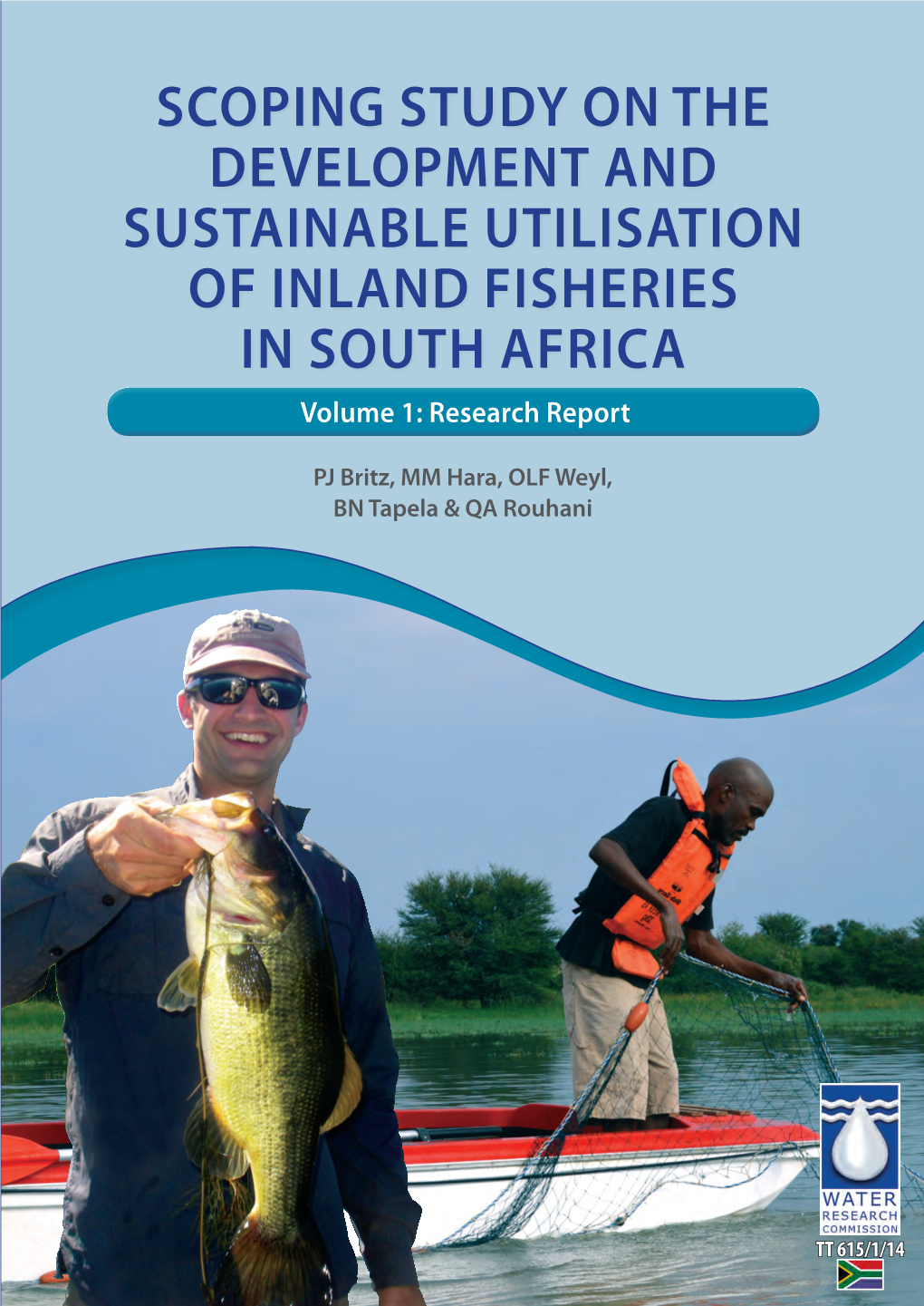

Scoping Study on the Development and Sustainable Utilisation of Inland Fisheries in South Africa Volume 1: Research Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Developmental Municipality That Ensures Sustainable Economic Growth and Equitable Service Delivery

MUTALE LOCAL MUNICIPALITY A DEVELOPMENTAL MUNICIPALITY THAT ENSURES SUSTAINABLE ECONOMIC GROWTH AND EQUITABLE SERVICE DELIVERY INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2016/17 5/30/2016 0 MAYORS FOREWORD It gives me pleasure to represent to you our integrated development plan for 2016/2017- which is a collective blueprint for future development trajectory of our municipality emanating from our continued engagement with our stakeholders. I therefore commend all our partners in development and stakeholders for their continued support in shaping our development. Census 2011 results on unemployment indicate that 40% of Mutale Local Municipality lives in poverty. This economic data compels us to marshal the municipality resources efficiently and complement the strategic role on national and provincial governments in creation of sustainable jobs. This IDP/Budget for 2016/2017 therefore opens yet another chapter in our gallant effort to dislodge the stranglehold of poverty and free more of our people out of hunger and diseases. We have also moved a step in a right direction by getting a qualified audit reports from the Auditor General in the previous financial year. It is the evidence of our hard work to ensure compliance and proper management of the public funds. We have, in this IDP, endeavored to present the development priorities contained in the election manifesto of the ANC, the party that is in government, as well as our constitutional mandate as the sphere of government that is closest to the people. The key word is delivery, service delivery alongside the infrastructure development that has become necessary to maintain acceptable life standard for all sectors of the local community. -

Conference Proceedings 2006

FOSAF THE FEDERATION OF SOUTHERN AFRICAN FLYFISHERS PROCEEDINGS OF THE 10 TH YELLOWFISH WORKING GROUP CONFERENCE STERKFONTEIN DAM, HARRISMITH 07 – 09 APRIL 2006 Edited by Peter Arderne PRINTING & DISTRIBUTION SPONSORED BY: sappi 1 CONTENTS Page List of participants 3 Press release 4 Chairman’s address -Bill Mincher 5 The effects of pollution on fish and people – Dr Steve Mitchell 7 DWAF Quality Status Report – Upper Vaal Management Area 2000 – 2005 - Riana 9 Munnik Water: The full picture of quality management & technology demand – Dries Louw 17 Fish kills in the Vaal: What went wrong? – Francois van Wyk 18 Water Pollution: The viewpoint of Eco-Care Trust – Mornē Viljoen 19 Why the fish kills in the Vaal? –Synthesis of the five preceding presentations 22 – Dr Steve Mitchell The Elands River Yellowfish Conservation Area – George McAllister 23 Status of the yellowfish populations in Limpopo Province – Paul Fouche 25 North West provincial report on the status of the yellowfish species – Daan Buijs & 34 Hermien Roux Status of yellowfish in KZN Province – Rob Karssing 40 Status of the yellowfish populations in the Western Cape – Dean Impson 44 Regional Report: Northern Cape (post meeting)– Ramogale Sekwele 50 Yellowfish conservation in the Free State Province – Pierre de Villiers 63 A bottom-up approach to freshwater conservation in the Orange Vaal River basin – 66 Pierre de Villiers Status of the yellowfish populations in Gauteng Province – Piet Muller 69 Yellowfish research: A reality to face – Dr Wynand Vlok 72 Assessing the distribution & flow requirements of endemic cyprinids in the Olifants- 86 Doring river system - Bruce Paxton Yellowfish genetics projects update – Dr Wynand Vlok on behalf of Prof. -

Review of Existing Infrastructure in the Orange River Catchment

Study Name: Orange River Integrated Water Resources Management Plan Report Title: Review of Existing Infrastructure in the Orange River Catchment Submitted By: WRP Consulting Engineers, Jeffares and Green, Sechaba Consulting, WCE Pty Ltd, Water Surveys Botswana (Pty) Ltd Authors: A Jeleni, H Mare Date of Issue: November 2007 Distribution: Botswana: DWA: 2 copies (Katai, Setloboko) Lesotho: Commissioner of Water: 2 copies (Ramosoeu, Nthathakane) Namibia: MAWRD: 2 copies (Amakali) South Africa: DWAF: 2 copies (Pyke, van Niekerk) GTZ: 2 copies (Vogel, Mpho) Reports: Review of Existing Infrastructure in the Orange River Catchment Review of Surface Hydrology in the Orange River Catchment Flood Management Evaluation of the Orange River Review of Groundwater Resources in the Orange River Catchment Environmental Considerations Pertaining to the Orange River Summary of Water Requirements from the Orange River Water Quality in the Orange River Demographic and Economic Activity in the four Orange Basin States Current Analytical Methods and Technical Capacity of the four Orange Basin States Institutional Structures in the four Orange Basin States Legislation and Legal Issues Surrounding the Orange River Catchment Summary Report TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................... 6 1.1 General ......................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Objective of the study ................................................................................................ -

Labeo Capensis (Orange River Mudfish) Ecological Risk Screening Summary

Orange River Mudfish (Labeo capensis) Ecological Risk Screening Summary U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, 2014 Revised, May and July 2019 Web Version, 9/19/2019 Image: G. A. Boulenger. Public domain. Available: https://archive.org/stream/catalogueoffres01brit/catalogueoffres01brit. (July 2019). 1 Native Range and Status in the United States Native Range From Froese and Pauly (2019): “Africa: within the drainage basin of the Orange-Vaal River system [located in Lesotho, Namibia, and South Africa] to which it is possibly restricted. Hitherto thought to occur in the Limpopo system and in southern Cape watersheds [South Africa] which records may be erroneous.” From Barkhuizen et al. (2017): “Native: Lesotho; Namibia; South Africa (Eastern Cape Province - Introduced, Free State, Gauteng, Mpumalanga, Northern Cape Province, North-West Province)” 1 Status in the United States This species has not been reported as introduced or established in the United States. There is no indication that this species is in trade in the United States. Means of Introductions in the United States This species has not been reported as introduced or established in the United States. Remarks A previous version of this ERSS was published in 2014. 2 Biology and Ecology Taxonomic Hierarchy and Taxonomic Standing From ITIS (2019): “Kingdom Animalia Subkingdom Bilateria Infrakingdom Deuterostomia Phylum Chordata Subphylum Vertebrata Infraphylum Gnathostomata Superclass Actinopterygii Class Teleostei Superorder Ostariophysi Order Cypriniformes Superfamily Cyprinoidea Family Cyprinidae Genus Labeo Species Labeo capensis (Smith, 1841)” From Fricke et al. (2019): “Current status: Valid as Labeo capensis (Smith 1841). Cyprinidae: Labeoninae.” Size, Weight, and Age Range From Froese and Pauly (2019): “Max length : 50.0 cm FL male/unsexed; [de Moor and Bruton 1988]; common length : 45.0 cm FL male/unsexed; [Lévêque and Daget 1984]; max. -

The Maloti Drakensberg Experience See Travel Map Inside This Flap❯❯❯

exploring the maloti drakensberg route the maloti drakensberg experience see travel map inside this flap❯❯❯ the maloti drakensberg experience the maloti drakensberg experience …the person who practices ecotourism has the opportunity of immersing him or herself in nature in a way that most people cannot enjoy in their routine, urban existences. This person “will eventually acquire a consciousness and knowledge of the natural environment, together with its cultural aspects, that will convert him or her into somebody keenly involved in conservation issues… héctor ceballos-lascuráin internationally renowned ecotourism expert” travel tips for the maloti drakensberg region Eastern Cape Tourism Board +27 (0)43 701 9600 www.ectb.co.za, [email protected] lesotho south africa Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife currency Maloti (M), divided into 100 lisente (cents), have currency The Rand (R) is divided into 100 cents. Most +27 (0)33 845 1999 an equivalent value to South African rand which are used traveller’s cheques are accepted at banks and at some shops www.kznwildlife.com; [email protected] interchangeably in Lesotho. Note that Maloti are not accepted and hotels. Major credit cards are accepted in most towns. Free State Tourism Authority in South Africa in place of rand. banks All towns will have at least one bank. Open Mon to Fri: +27 (0)51 411 4300 Traveller’s cheques and major credit cards are generally 09h00–15h30, Sat: 09h00–11h00. Autobanks (or ATMs) are www.dteea.fs.gov.za accepted in Maseru. All foreign currency exchange should be found in most towns and operate on a 24-hour basis. -

European Methods to Catchthe Illustrious

European Methods to Catch the Illustrious CARP photo-Jim Gronaw favorite.” But, he does “put carp ahead of Largemouth by Marilyn Black Bass and trout, because carp are far more difficult to catch than most people think.” Although he does not eat carp, Gronaw fishes for them, because they are big. “I love big fish,” said Gronaw. For the past 8 years, Gronaw has been fishing for carp Just as Aretha Franklin declared in song, she’s looking for with the European/bite alarm methodology, strictly from respect. Carp fishing in the United States today is also shore. “Carp fishing is most successful with a still, static looking for respect. In fact, carp should be viewed as an presentation, which includes bringing carp to a particular acronym for “Cautious, Alien, Rugged and Powerful,” area by pre-baiting with prepared corn, and then providing which they certainly are when caught on hook and line. The the bottom feeders with sweet items on a hook or hair rig, current State Record Common Carp was caught in 1962. said Gronaw.” The fish weighed 52 pounds and was taken from the Juniata River in Huntingdon County by George Brown, Saltillo. European technique The Common Carp species (Cyprinus carpio) originated Methods and equipment developed in Europe have in Europe. Breaded and fried, it’s part of traditional proven effective stateside. Generally speaking, serious carp Christmas Eve dinners in Poland and in the Czech anglers use baitrunner style spinning reels that can easily Republic. Originally introduced to the United States by handle 15-pound-test monofilament line, paired with 9- to the Pennsylvania Fish Commission in the 1870s as a fish 11-feet rods for distance casting. -

Biodiversity Plan V1.0 Free State Province Technical Report (FSDETEA/BPFS/2016 1.0)

Biodiversity Plan v1.0 Free State Province Technical Report (FSDETEA/BPFS/2016_1.0) DRAFT 1 JUNE 2016 Map: Collins, N.B. 2015. Free State Province Biodiversity Plan: CBA map. Report Title: Free State Province Biodiversity Plan: Technical Report v1.0 Free State Department of Economic, Small Business Development, Tourism and Environmental Affairs. Internal Report. Date: $20 June 2016 ______________________________ Version: 1.0 Authors & contact details: Nacelle Collins Free State Department of Economic Development, Tourism and Environmental Affairs [email protected] 051 4004775 082 4499012 Physical address: 34 Bojonala Buidling Markgraaf street Bloemfontein 9300 Postal address: Private Bag X20801 Bloemfontein 9300 Citation: Report: Collins, N.B. 2016. Free State Province Biodiversity Plan: Technical Report v1.0. Free State Department of Economic, Small Business Development, Tourism and Environmental Affairs. Internal Report. 1. Summary $what is a biodiversity plan This report contains the technical information that details the rationale and methods followed to produce the first terrestrial biodiversity plan for the Free State Province. Because of low confidence in the aquatic data that were available at the time of developing the plan, the aquatic component is not included herein and will be released as a separate report. The biodiversity plan was developed with cognisance of the requirements for the determination of bioregions and the preparation and publication of bioregional plans (DEAT, 2009). To this extent the two main products of this process are: • A map indicating the different terrestrial categories (Protected, Critical Biodiversity Areas, Ecological Support Areas, Other and Degraded) • Land-use guidelines for the above mentioned categories This plan represents the first attempt at collating all terrestrial biodiversity and ecological data into a single system from which it can be interrogated and assessed. -

Evaluating the Criteria for Allocation of Development Projects in the Context of Spatial Development Frameworks in Thulamela Local Municipality

EVALUATING THE CRITERIA FOR ALLOCATION OF DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS IN THE CONTEXT OF SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORKS IN THULAMELA LOCAL MUNICIPALITY BY THIBA M.C UNIVERSITY OF VENDA 2018 UNIVERSITY OF VENDA SCHOOL OF ENVIRONMELTAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF URBAN AND REGIONAL PLANNING DISSERTATION TITLE: EVALUATING THE CRITERIA FOR ALLOCATION OF DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS IN THE CONTEXT OF SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORKS IN THULAMELA LOCAL MUNICIPALITY BY THIBA MC STUDENT NO: 11523180 SUPERVISOR: Prof P. BIKAM CO-SUPERVISOR: Dr J. CHAKWIZIRA THIS DISSERTATION IS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE M.URP DEGREE TO THE DEPARTMENT OF URBAN AND REGIONAL PLANNING UNDER THE SCHOOL OF ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF VENDA DECLARATION I, Thiba M.C declare that this research titled “Evaluating the criteria for allocation of development projects to communities using Spatial Development Frameworks in Thulamela local municipality” is my own work, it has never been submitted for another degree at any university and all reference material contained therein has been duly acknowledged. Student’s Signature…………………………………………. Date………………………………… Supervisor: Prof P. Bikam Signature…………………………………………. ……………Date………………………………… Co-Supervisor: Dr James Chakwizira Signature…………………………………………. ……………Date………………………………… HOD: Dr James Chakwizira Signature…………………………………………. ……………Date………………………………… Evaluating the Criteria for Allocation of Development Projects in the Context of Spatial Development Frameworks in Thulamela Local Municipality i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is a great pleasure to acknowledge the assistance I have received in conducting this research which has culminated in the writing of this dissertation. I wish to express my indebtedness’s to Prof. Peter Bikam, my supervisor, for his inspiring guidance, constructive criticisms and invaluable supervision during the preparation of this dissertation. -

In This Issue

VOLUME 22, NUMBER 2 FREE JULY 2012 TM in This issue FREE THIS ISSUE COMPLIMENTS OF • The carp whisperer • diamond jim on The loose • mahi - mahi • Gunpowder Bass challenGe 2012 • pittman - roBerTson acT 75 Years of savinG america’s wildlife July 2012 www.fishingandhuntingjournal.com 1 $10,000 Diamond Jim on the Loose More than $25,000 in prizes up for grabs during this year’s DNR fishing challenge The hunt is on. The Diamond 600 imposters worth at least $500 passes to the Maryland Fishing Jim component of the 2012 Mary- each and one genuine Diamond Challenge Finale, which will land Fishing Challenge kicked off Jim will be pursued by anglers. be held in conjunction with the today when Maryland Department Each month Diamond Jim goes Maryland Seafood Festival at of Natural Resources (DNR) biolo- uncaught the bounty increases ─ Sandy Point State Park on Sep- gists and some eager young an- from $10,000 in June, to $20,000 tember 8, 2012. This year’s Cel- glers caught, tagged and released in July, and $25,000 in August. ebration will include chances dozens of striped bass into the The contest features a guaran- to win a boat, trailer and motor Chesapeake Bay. One of today’s teed $25,000 payout: If Diamond package from Tracker Marine, a tagged fish is the official Diamond Jim is not caught by Labor Day, tropical vacation package from Jim worth $10,000 to the angler the cash prize will be split equally the World Fishing Network, who catches it before midnight on among the anglers who catch im- tackle packages from Bill’s June 30. -

Outdoorillinois July 2005 What's a Boile Bait?

Paul Wells takes dough ball baits to a new level. WWhhaatt’’ss aa BBooiillee BBaaiitt?? ost ingredients for boilie baits can Mbe found at natural, organic or health food stores, or food cooperatives. Search the Internet for the term “hair rig” to learn how to fish boilies off the hook. 50/50 Base Mix 8 oz. semolina flour 4 oz. soy flour 4 oz. yellow corn meal 5 ml. mulberry florentine or another strong fruit flavoring 5 to 10 ml. liquid saccharine 10 ml. corn steep liquor (corn flavoring) 1 ⁄4 tsp. garlic powder Story By P.J. Perea 5 to 6 large eggs Photos by Adele Hodde Bird Food Mix 6 oz. bird food (pellets not bird seeds) 6 oz. semolina flour 4 oz. soy flour he delectable aromas wafting For a different twist on carp 2 oz. whey 5 ml. butterscotch, vanilla or other from Chicagoan Paul Wells’ fishing, and to keep the fish kitchen spell trouble, not for his creamy flavor guessing, experiment with crafting 5 ml. liquid saccharine waistline but for the target of an 1 homemade boilie baits. ⁄4 tsp. garlic powder T upcoming fishing expedition— 5 to 6 large eggs the common carp, a plentiful, transplant - For either recipe: ed species that has taken over many OK to eat and what will one day have a Mix the ingredients in a bowl until a river and lake systems. hidden hook. stiff and slightly sticky dough has Wells’ kitchen concoctions are boilie “I recommend carp anglers fish formed. Roll into long strips, cut and roll baits, a European creation designed to slow- to medium-flowing waters at first into bait-sized balls. -

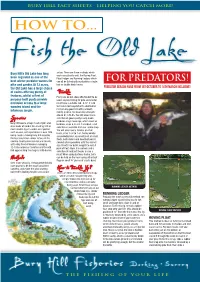

Learn How to Fish the Old Lake for Predators

BURY HILL FACT SHEETS - helping you catch more! HOW TO... Fish the Old Lake Bury Hill’s Old Lake has long action. There are three methods which work consistently well, the Roving Float, been regarded as one of the Float Ledger and Running Ledger, which FOR PREDATORS! best winter predator waters for can all be fished with our barbless single, pike and zander. At 12 acres, hair or double hook traces. the Old Lake has a large choice PREDATOR SEASON RUNS FROM 1ST OCTOBER TO 14TH MARCH INCLUSIVE! of swims offering plenty of Tackle features, whilst a fleet of Firstly we do not allow SEA TACKLE to be purpose built punts provide used, anyone fishing for pike and zander exclusive access to a large must have a suitable rod. A 12’ 2 ¾ lb wooded island and the test curve rod coupled with a baitrunner infamous jungle. reel (or any good reel with a smooth clutch) is ideal, minimum line strength should be 12lb BS. You will also need a selection of good quality ready-made Species predator single hook rigs, which must be Bury Hill boasts a huge head of pike and barbless, sizes 8, 6 and 4 are ideal, a full shed loads of zander. An amazing 100 or selection is available from our tackle shop. more double-figure zander are reported You will also need a handful of small each season, with specimens to over 16lb leads, sizes ½ oz to 2 oz, Arsley bombs being caught, making Bury Hill arguably are probably best, an assortment of small the best day ticket zander fishery in the floats, both sliders and dead bait pencil country. -

Private Game Reserves and State Reserves

PRIVATEGAMERESERVESANDSTATERESERVES 59 PRIVATEGAMERESERVESANDSTATERESERVES P. Knott,*H. Knott*,J. Kruger**C.vanderWaal*** *Greater Kuduland Safaris ***Mara Resaerch Station Sourcesofinformation • Plaas Marius and Conservancy, 5000 ha: plains gameandLeopard. The information on game ranching in the study area is Lesheba Ranch, not sure about size: plains game and scant. Limpopo Province’s Department of Finance and • Rhino. Environmental Affairs have a database of game ranches with exemption permits. This database is not complete. • Goro Ranch,7000ha:plainsgame. 17 of the more prominent ranches and reserves in the • Bergtop Ranch,4000ha:plainsgameandRhino. study area cover an area in excess of 150 000 ha. Com- pared to provincial statistics for 1998, 26% of the surface • Western Soutpansberg Conservancy, 90000 ha, area of the province was game fenced by that time. It has plainsgameandLeopard. been estimated that more than 80% of former cattle farms • Blouberg NatureReserve,8000ha:plainsgame. have been converted to game ranches in the area north of the Soutpansberg Mountain. Obviously the database is • Maleboch NatureReserve,5000ha:plainsgame. not complete and needs updating. Game resources are utilised in different ways. These in- Summarystatistics clude hunting, live capture, intensive breeding and non-consumptive eco-tourism activities (photo safaris, Large mammals commonly found on game ranches in the etc.). area include: kudu, impala, blue wildebeest, zebra, gi- raffe, warthog, gemsbuck, eland, leopard, brown hyena Majorstudiesandpublications and bushpig. Species that have been re-introduced in- clude: sable, roan, buffalo, elephant, nyala, waterbuck, DU TOIT, J. T. 1995. Determinants of the composition white rhino and lion. and distribution of wildlife communities in Southern Africa. Ambio 24(1):2–6.