Learning Web Page Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dossier De Presse Winterhalter

dossier de presse Winterhalter Portraits de cour, entre faste et élégance 30 septembre 2016 - 15 janvier 2017 Musées nationaux du palais de Compiègne place du Général de Gaulle, 60200 Compiègne communiqué p.02 press release p.04 chronologie p.06 parcours muséographique p.08 textes des sections p.09 liste des œuvres exposées p.13 catalogue de l’exposition p.16 extraits du catalogue p.17 quelques notices d’œuvres p.23 programmation culturelle p.32 informations pratiques p.33 les Musées et domaine nationaux du Palais de Compiègne p.34 Spectaculaire Second Empire (1852-1870), au musée d’Orsay p.35 visuels disponibles pour la presse p.37 partenaires média p.41 Franz Xaver Winterhalter, L’Impératrice Eugénie entourée de ses dames d’honneur, 1855, huile sur toile ; 295 x 420 cm, Compiègne, musées nationaux du palais de Compiègne, dépôt du musée national du château de Malmaison, Photo © Rmn-Grand Palais (domaine de Compiègne) / Droits réservés communiqué Winterhalter Portraits de cour, entre faste et élégance 30 septembre 2016 - 15 janvier 2017 Musées nationaux du palais de Compiègne place du Général de Gaulle, 60200 Compiègne Cette exposition est organisée par les musées nationaux du palais de Compiègne et la Réunion des musées nationaux-Grand Palais, les Städtische Museen Freiburg, et The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Dernier grand peintre de cour que l’Europe ait connu, Franz Xaver Winterhalter eut un destin exceptionnel. Né en 1805 dans une humble famille d’un petit village de la Forêt noire, il fit ses études artistiques à Munich, puis fut nommé peintre de la cour de Bade. -

Artists` Picture Rooms in Eighteenth-Century Bath

ARTISTS' PICTURE ROOMS IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY BATH Susan Legouix Sloman In May 1775 David Garrick described to Hannah More the sense of well being he experienced in Bath: 'I do this, & do that, & do Nothing, & I go here and go there and go nowhere-Such is ye life of Bath & such the Effects of this place upon me-I forget my Cares, & my large family in London, & Every thing ... '. 1 The visitor to Bath in the second half of the eighteenth century had very few decisions to make once he was safely installed in his lodgings. A well-established pattern of bathing, drinking spa water, worship, concert and theatre-going and balls meant that in the early and later parts of each day he was likely to be fully occupied. However he was free to decide how to spend the daylight hours between around lOam when the company generally left the Pump Room and 3pm when most people retired to their lodgings to dine. Contemporary diaries and journals suggest that favourite daytime pursuits included walking on the parades, carriage excursions, visiting libraries (which were usually also bookshops), milliners, toy shops, jewellers and artists' showrooms and of course, sitting for a portrait. At least 160 artists spent some time working in Bath in the eighteenth century,2 a statistic which indicates that sitting for a portrait was indeed one of the most popular activities. Although he did not specifically have Bath in mind, Thomas Bardwell noted in 1756, 'It is well known, that no Nation in the World delights so much in Face-painting, or gives so generous Encouragement to it as our own'.3 In 1760 the Bath writer Daniel Webb noted 'the extraordinary passion which the English have for portraits'.4 Andre Rouquet in his survey of The Present State of the Arts in England of 1755 described how 'Every portrait painter in England has a room to shew his pictures, separate from that in which he works. -

Eugene Barilo Von Reisberg, M

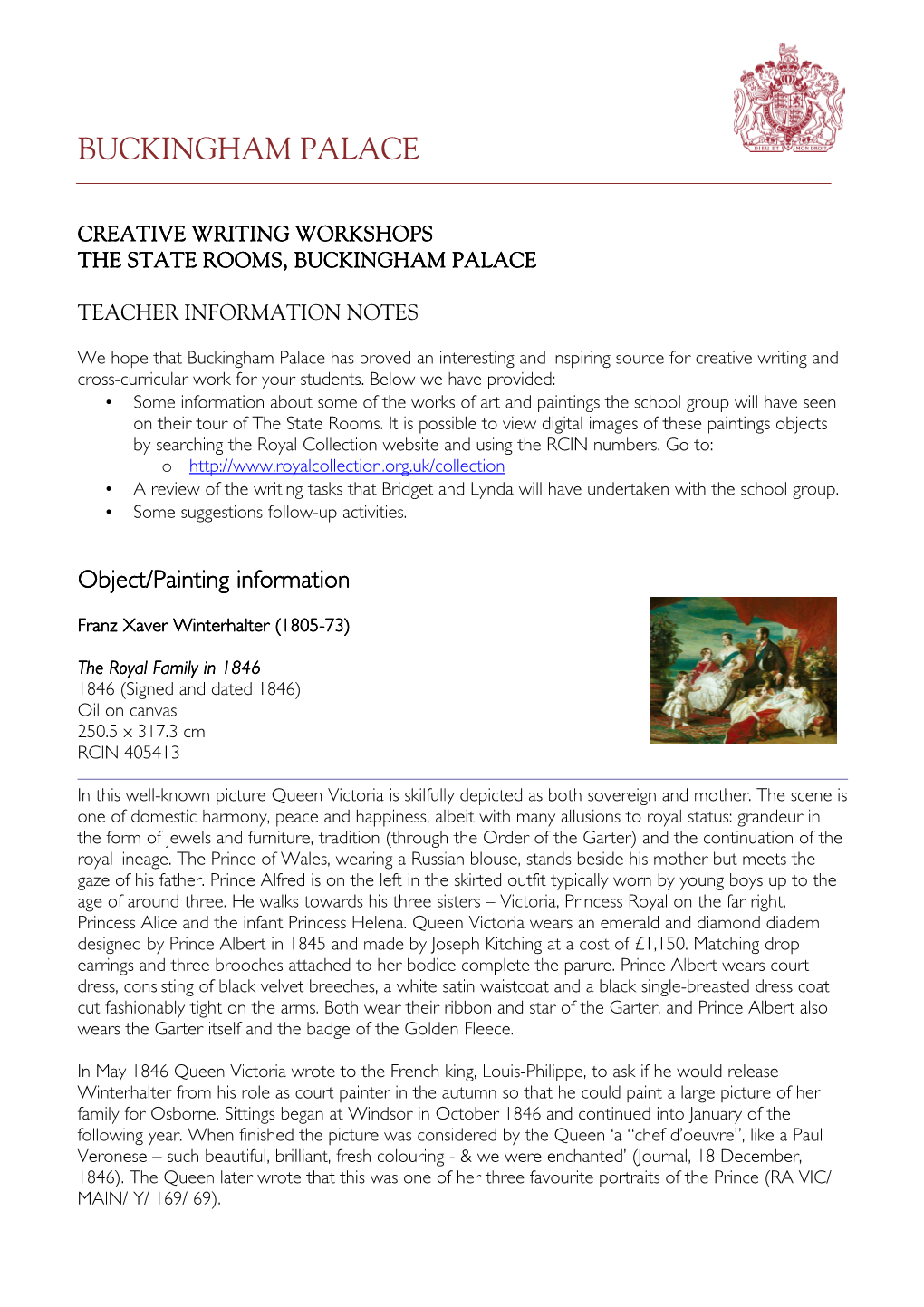

Eugene Barilo von Reisberg, Garters and Petticoats: Franz Xaver Winterhalter’s 1843 Portraits of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert EUGENE BARILO VON REISBERG Garters and Petticoats: Franz Xaver Winterhalter’s 1843 Portraits of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert ABSTRACT What does official royal iconography tell us? What messages does it communicate about the sitters – and from the sitters? This paper deconstructs two official portraits of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert painted by Franz Xaver Winterhalter (1805-1873) in 1843. It outlines the complex semantic layering within this pair of British royal portraits, and explores in particular the emphasis on Prince Albert‘s newly-acquired ‗Englishness‘ and the notion of an iconographic ‗gender reversal‘ within the context of traditional marital pendants. The Honourable Eleanor Stanley wrote in a letter that a ‗regular dull evening‘ at Windsor Castle on 24 March 1845 was enlivened by the youthful Queen Victoria‘s impassioned speech about the state of British portraiture, ‗a terrible broadside at English artists, both as regards their works and … their prices, and their charging her particularly outrageously high.‘1 The twenty-six-year-old queen spoke from experience. As the heir apparent to the British throne, she had been painted from infancy by a succession of artists, vying for the patronage of the future sovereign. From her accession in 1837, the queen sat to numerous painters who failed to satisfy the requirements of official portraiture in the eyes of the monarch, her courtiers, and the critics. David Wilkie‘s (1785-1841) portrait of the queen was condemned by the critics as being ‗execrable‘.2 The queen considered her portrait by Martin Archer Shee (1769- 1850) as ‗monstrous‘;3 while the Figaro compared her countenance in the portrait by George Hayter (1792-1871) as that of an ‗ill-tempered and obstinate little miss.‘4 Portraits of Prince Albert, whom the queen married in February 1840, did not fair much better. -

BADISCHE HEIMAT M Ein Heimatland 53

BADISCHE HEIMAT M ein Heimatland 53. Jahrg. 1973, Heft 3 Zum 100.Todestag des Malers Franz Xaver Winterhalter Am 8. Juli 1973 veranstaltete die nie verleugneten Heimat und Herkunft. In Schwarz waldgemeinde Menzenschwand zur seinem Testament hat der Künstler den Ge Erinnerung an ihren großen Sohn eine wür meinden Menzenschwand Vorderhof und dige Feierstunde, bei der Dr. Werner Zim Hinterdorf eine Stiftung von 50 000 Fr. aus mermann von der Staatl. Kunsthalle Karls gesetzt, die Winterhalter-Stiftung genannt ruhe folgende Gedenkrede hielt: werden sollte, und deren Zinsen zur Unter stützung der Jugend, die nützliche Hand Wir sind hier zusammengekommen, um werke, Künste oder Wissenschaften erlernen des großen Sohnes der Gemeinde Menzen wollte und teils zur Unterstützung Hilfs schwand zu gedenken, des Malers Franz bedürftiger und Armer verwendet werden Xaver Winterhalter, der heute vor 100 sollten. Jahren die Augen für immer geschlossen hat. F. X. Winterhalter wurde am 20. April Ein arbeitsreiches und bewegtes Leben lag 1805 hier in Menzenschwand geboren. Zwei hinter ihm, in welchem ihm als dem ge Schwestern, Justine und Theresia, waren vor feiertsten Porträtmaler seiner Zeit Ruhm ihm geboren worden. Am 23. September und Bewunderung in einem Maße zuteil ge 1808 erblickte Hermann, als Jüngster der worden waren, wie das keinem deutschen Geschwister, das Licht der Welt. Er blieb Maler des 19. Jh. zu Lebzeiten je vergönnt wie Franz Xaver unverheiratet und ist gewesen ist. Alles was Rang und Namen im diesem ein treuer Freund und Mitarbeiter damaligen Europa besaß, hat Winterhalter geworden. In beiden Brüdern muß die gehuldigt und mit Recht wird er der Prin künstlerische Neigung schon früh erwacht zen- oder Fürstenmaler genannt; denn die sein. -

The Dispersal and Formation of Sir Thomas Lawrence's Collection

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-55133-5 - The Drawings of Michelangelo and his Followers in the Ashmolean Museum Paul Joannides Excerpt More information the dispersal and formation of sir thomas lawrence’s collection of drawings by michelangelo i. the dispersal from Michelangelo apart – in its essentials has not changed since 1846, although one sheet of drawings hitherto In 1846 the University of Oxford acquired, through the placed in the Raphael school is here included as a copy generosity of a number of benefactors but supremely that after Michelangelo – an identification, indeed, made in of Lord Eldon, a large number of drawings by, attributed 1830 but subsequently overlooked.5 to, or associated with Michelangelo and Raphael. Put The two series that came to Oxford were the remains on display in the University Galleries were fifty-three of two much larger series of drawings, both owned by mountings of drawings associated with Michelangelo, and the man who has clear claim to be the greatest of all 137 by Raphael.1 Some of these mountings comprised English collectors of Old Master Drawings: Sir Thomas two or more drawings and the overall total of individual Lawrence. It is Lawrence’s collection that provided all drawings was somewhat larger.2 This exhibition and – the drawings by, and most of those after, Michelangelo consequently – its catalogue included most, but not the now in the Ashmolean Museum. Lawrence, himself a totality, of the drawings by these artists offered for sale fine draughtsman, whose precision and skill in this area -

The Origins and Nature of Romanticism This Evening I Want To

The Origins and Nature of Romanticism This evening I want to say something about the origin and nature of romanticism. Generally speaking, it would be fair to conclude, it seems to me, that the neo-classical movement was official, conservative and in its later phases actively reactionary in the rigidity of its rules, though must qualify this by observing that early neo-classical architectural theory and practice gave birth to the modern theory of functionalism, so important for the twentieth century, and neo-classical paining in France under David gave birth to realism, so important for nineteenth century French painting. There can be no doubt that after 1815 the Romantic movement expressed the tensions and mood of the new age more profoundly than Neo-classicism. ‘To say the word Romanticism is to say modern art—that is, intimacy, spirituality, colour, aspiration towards the infinite, expressed by every means available to the arts’ wrote Baudelaire in his critical review of the Salon of 1846. ‘For me, Romanticism is the most recent, the latest expression of the beautiful’. The sources of romanticism lie outside of art itself and I shall not discuss them in detail, for they are often discussed. The rise of popular democracy, of industrialism, and of capitalism, changed utterly the artist’s relation to society. He importance of his old patrons the church, the court, the nobility declined swiftly. In the new situation the artist became an individualist forced to rely upon himself. Romanticism was the consequence of the new situation. It was not a style like Gothic or Baroque (this is important to grasp at once) not a style but as Baudelaire says ‘a mode of feeling’. -

Franz Xavier Winterhalter

Franz Xavier Winterhalter German painter, 1805-1873 Franz Xaver Winterhalter (20 April 1805 – 8 July 1873) was a German painter and lithographer, known for his portraits of royalty in the mid-nineteenth century. His name has become associated with fashionable court portraiture. Among his best known works are Empress Eugénie Surrounded by her Ladies in Waiting (1855) and the portraits he made of Empress Elisabeth of Austria (1865). Katarzyna Branicka Countess Potocka Picture ID 37239-Katarzyna_Branicka_Countess_Potocka.jpg Oil Painting ID: 37239 La Siesta Picture ID 37240-La_Siesta.jpg Oil Painting ID: 37240 Lady Clementina Augusta Wellington Child Villiers Picture ID 37241-Lady_Clementina_Augusta_Wellington_Child_Villiers.jpg Oil Painting ID: 37241 Leopold Duke of Brabant Picture ID 37242-Leopold_Duke_of_Brabant.jpg Oil Painting ID: 37242 1/6 Madame Sofya Petrovna Naryschkina Picture ID 37243-Madame_Sofya_Petrovna_Naryschkina.jpg Oil Painting ID: 37243 Malcy Louise Caroline Frederique Berthier de Wagram Princess Murat Picture ID 37244-Malcy Louise Caroline Frederique Berthier de Wagram Princess Murat.jpg Oil Painting ID: 37244 Melanie de Bussiere Comtesse Edmond de Pourtales Picture ID 37245-Melanie_de_Bussiere_Comtesse_Edmond_de_Pourtales.jpg Oil Painting ID: 37245 Napoleon Alexandre Louis Joseph Berthier Picture ID 37246-Napoleon_Alexandre_Louis_Joseph_Berthier.jpg Oil Painting ID: 37246 Pauline Sandor Princess Metternich Picture ID 37247-Pauline_Sandor_Princess_Metternich.jpg Oil Painting ID: 37247 2/6 Portrait of a Lady -

Born in 1769, by the Age of 10 Thomas Lawrence Was Already Showing Remarkable Artistic Ability. Our Expert, Amina Wright, Explor

BY ARTS SOCIETY LECTURER AMINA WRIGHT Born in 1769, by the age of 10 Thomas Lawrence was already showing remarkable artistic ability. Our expert, Amina Wright, explores the story of the boy that went on to become president of the Royal Academy of Arts 1. PORTRAIT OF THE ARTIST AS A YOUNG PRODIGY The portrait painter Thomas Lawrence first came to public attention as a boy in the 1770s, when his father kept a superior coaching inn, the Black Bear at Devizes, Wiltshire. Travelling from London to the fashionable spa town of Bath, the novelist, diarist and playwright Fanny Burney was one of many famous guests at the Bear; stopping there in 1780 she found the innkeeper’s family to be well read and musically gifted. Their youngest son, Thomas, was ‘a most lovely boy of 10 years of age, who seems to be not merely the wonder of their family, but of the times for his astonishing skill in drawing'. The actor David Garrick, a regular at the Bear, was equally impressed by Tommy’s acting skills and he foresaw his future success ‘poised between the pencil and the stage’. The child regularly attended performances at the Theatre Royal in Bath with his father, an aspiring thespian and poet who would return actors’ hospitality in the green room with a welcome at the Bear. This ensured that Lawrence’s reputation as a rising star spread through the literary and artistic networks of Bath and Wiltshire. Head of Minerva Drawn at Oxford by Master Lawrence at the Age of 11 Years (1779) 2. -

The Patronage and Collections of Louis-Philippe and Napoléon III During the Era of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert

Victoria Albert &Art & Love Victoria Albert &Art & Love The patronage and collections of Louis-Philippe and Napoléon III during the era of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert Emmanuel Starcky Essays from a study day held at the National Gallery, London on 5 and 6 June 2010 Edited by Susanna Avery-Quash Design by Tom Keates at Mick Keates Design Published by Royal Collection Trust / © HM Queen Elizabeth II 2012. Royal Collection Enterprises Limited St James’s Palace, London SW1A 1JR www.royalcollection.org ISBN 978 1905686 75 9 First published online 23/04/2012 This publication may be downloaded and printed either in its entirety or as individual chapters. It may be reproduced, and copies distributed, for non-commercial, educational purposes only. Please properly attribute the material to its respective authors. For any other uses please contact Royal Collection Enterprises Limited. www.royalcollection.org.uk Victoria Albert &Art & Love The patronage and collections of Louis-Philippe and Napoléon III during the era of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert Emmanuel Starcky Fig. 1 Workshop of Franz Winterhalter, Portrait of Louis-Philippe (1773–1850), 1840 Oil on canvas, 233 x 167cm Compiègne, Musée national du palais Fig. 2 After Franz Winterhalter, Portrait of Napoleon III (1808–1873), 1860 Tapestry from the Gobelin manufactory, 241 x 159cm Compiègne, Musée national du palais The reputation of certain monarchs is so distorted by caricaturists as to undermine their real achievements. Such was the case with Louis-Philippe (1773–1850; fig. 1), son of Philippe Egalité, who had voted for the execution of his cousin Louis XVI, and with his successor, Napoléon III (1808–73; fig. -

Was Queen Charlotte Black? | the Hook - Charlottesville's Weekly News

Was Queen Charlotte black? | The Hook - Charlottesville's weekly news... http://www.readthehook.com/98341/cover-was-queen-charlotte-black COVER STORIES Was Queen Charlotte black? By VIRGINIA DAUGHERTY Published online Thursday Feb 2nd, 2006 and in print issue #0505 dated Thursday Feb 2nd, 2006 Was Queen Charlotte, our city's namesake, black? Her African heritage is part of the legends and facts that cling to the petite German woman who married "mad King George" and who inspired not only Charlotte, North Carolina, but at least eight other places in North America– including our town. Although she was German, Charlotte was directly descended from Margarita de Castro y Sousa, a member of the black branch of the Portuguese royal house. Whether her lineage affected her appearance is contested. Historian Mario de Valdes y Cocom says that her features, as seen in royal portraits, were conspicuously "negroid" and reports that they were noted by numerous contemporaries including the queen's personal physician, Baron Stockmar, who described her at age 84 as "small and crooked, with a true mulatto face." Wikipedia, the online encyclopedia, explains that Charlotte's ancestor, Margarita de Castro, descended from Portuguese monarch Alfonso III and his mistress, Mourana Gil, an African of Moorish descent. The Wikipedia blog contains an ongoing argument, with one blogger writing, "This is precisely the kind of thing historians would love to cover up." Another objects, "The whole 'Queen Charlotte was black' thing is total garbage." A third answers, "It's apparent that racist sentiments seem to find their way into the simplist [sic] of argume nts." "An African ancestry doesn't mean she's black." "It is actually quite certain that all European royalty has a slight amount of black ancestry." And so on. -

Expert Adviser's Statement.Pdf

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Brief Description of item Watercolour by John Martin (1789-1854) (b. Heydon Bridge, Northumberland, d. Douglas, Isle of Man), The Destruction of Pharaoh’s Host, signed and dated: ‘J. Martin/1836’ (lower right) Pencil and watercolour with gum arabic heightened with bodycolour and with scratching out; 23 x 33 ¾ in. (584 x 857 mm) (No condition report provided) The watercolour illustrates the passage in Exodus, 14:26-31, when the Lord instructed Moses to stretch out his hand to release the waters and drown the Egyptians pursuing the fleeing Israelites across the Red Sea which had been miraculously parted to allow them passage: And the waters returned, and covered the chariots and the horsemen, and all the host of Pharaoh that came into the sea after them; and there remained not so much as one of them. But the children of Israel walked upon dry land in the midst of the sea; and the waters were a wall unto them on the right hand, and on their left. Moses stands on a promontory on the right of the image, commanding the waters, accompanied by the saved Israelites. Employing a panoramic composition to magnificent effect, Martin exaggerates the scale of the waves by sketching in the massed crowds of Israelites along the coast to the right and by diminishing the size of the drowning figures, horses and chariots, and two pyramids on the horizon. A blood red sunset below a sweeping black sky symbolizing mass death and retribution looms over the Red Sea. 2. Context Provenance and Prices (Probably) J.E. -

Dokumente Zu Leben Und Werk

waren Architektur, Kunst und Historie. Mit seiner Gemahlin hatte er acht Kinder, von denen der zweite Sohn, Prinz Friedrich von Baden, als Großherzog Friedrich I. sein Nachfolger wurde. Gleich nach seinem Regierungsantritt (J 830) wurde W. mit der Ausführung der offiziellen Herrscherporträts beauftragt. Die hier gezeigten, durch Lithographie im ganzen Land verbrei teten Porträts zeigen den Großherzog mit einer Schriftrolle, wohl der Verfassung, als konstitu tionell regierenden Landesvater. W. erhielt 1832 das Großherzogliehe Privileg für das alleinige Recht zur lithographischen Vervielfältigung dieser Portraits (s. Dokumente V). Leopold unterstützte W. durch Stipendien, die diesem auch die für ihn so bedeutsame Italienreise in den Jahren 1832-34 ermöglichten, und ernannte ihn dann 1834 zum Badischen Hofmaler. Im Dezember 1834, kurze Zeit nach der Rückkehr aus Italien, siedelte W. nach Paris um und begann damit seine mehr als 35 Jahre dauernde Pariser Zeit, bis er während des Deutsch-Französischen Krieg 1870/71. den er in der Schweiz erlebte, seinen Wohnsitz zu sammen mit seinem Bruder Herrmann F. wieder in Karlsruhe nahm. Die biographischen Angaben sind folgenden Werken entnommen: Ehlert, Michael: Familiengeschichte von Menzenschwand, St. Blasien 1998; für Menzenschwander Daten. Häusler, Gustav: Der Maler Johann Martin Morat aus Stühlingen, in: Mein Heimatland No. 25, 1938, S. 271; zu dem Maler Morat, der die alten Dorfansichten von Menzenschwand (um 1860) ge malt hat Hirsch, Flitz: 100 Jahre Bauen und Schauen, Bd. 2, Karlsruhe 1932; für von EichthaI, Kusel, Berck müller und die Großherzogliche Familie. Klüber, Karl Wemer: Hans Thomas Ahnenschaft, in: Mein Heimatland No. 21. 1939, S. 337 ff.; für Winterhalter-Ahnen. Meister, Fl'anz: Das alte Herdersche Kunstinstitut, Fl'eiburg 1916, S.