Sir Thomas Lawrence and the Waterloo Chamber

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tour of Windsor Castle

--Tour of Windsor Castle-- APPENDIX A TOUR OF WINDSOR CASTLE I. Castle layout and external tour (see Page # 4 for the State Apartment tour) A. Main Lower Ward entrance to castle 1. Built by King Henry VIII and named after him 2. Completed in 1509 A.M. 3. Over the archway are: a) Carving of (1) The King's arms (2) A Tudor Rose (3) A pomegranate, badge of Henry's first queen, Catherine of Aragon b) The carvings are repeated above in the battlements 4. St. George's Chapel stands on the opposite side of the Lower Ward from the Henry VIII gate a) St. George's is the spiritual center of the Order of the Garter b) Charles I, beheaded in 1649 during England's Civil War, is buried here 5. The parade ground is to the left, where changing of the guard occurs in winter 6. Between parade ground and St. George's Chapel is small gate leading to the Horseshoe Cloister a) A row of houses built by King Edward IV in 15th century for lesser clergy b) Now houses men singers of the choir and the sacristans c) Was restored in 19th century 7. The Curfew Tower stands just beyond the Cloister and at the castle's westerly extreme (where castle meets Thames Street) a) Built in 13th century b) Part of the last section of the outer wall to be constructed c) Contains: (1) Fine example of a medieval dungeon in basement (2) One end of secret, underground exit from the castle, or "sally port," now sealed at its other entrance A-1 --Tour of Windsor Castle-- (3) Upper story contains the eight bells of St. -

London Calling: BBC External Services, Whitehall and the Cold War 1944- 57

London calling: BBC external services, Whitehall and the cold war 1944- 57. Webb, Alban The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author For additional information about this publication click this link. http://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/jspui/handle/123456789/1577 Information about this research object was correct at the time of download; we occasionally make corrections to records, please therefore check the published record when citing. For more information contact [email protected] LONDON CALLING: SSC EXTERNAL SERVICES, WHITEHALL AND THE COLD WAR, 1944-57 ALBAN WEBB Queen Mary College, University of London A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of London for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D) 1 Declaration: The work presented in this thesis is my own. Signed: '~"\ ~~Ue6b Alban Webb Declaration: The work presented in this thesis is my own. Signed: Alban Webb ABSTRACT The Second World War had radically changed the focus of the BBC's overseas operation from providing an imperial service in English only, to that of a global broadcaster speaking to the world in over forty different languages. The end of that conflict saw the BBC's External Services, as they became known, re-engineered for a world at peace, but it was not long before splits in the international community caused the postwar geopolitical landscape to shift, plunging the world into a cold war. At the British government's insistence a re-calibration of the External Services' broadcasting remit was undertaken, particularly in its broadcasts to Central and Eastern Europe, to adapt its output to this new and emerging world order. -

Russian Art+ Culture

RUSSIAN ART+ CULTURE WINTER GUIDE RUSSIAN ART WEEK, LONDON 23-30 NOVEMBER 2018 Russian Art Week Guide, oktober 2018 CONTENTS Russian Sale Icons, Fine Art and Antiques AUCTION IN COPENHAGEN PREVIEW IN LONDON FRIDAY 30 NOVEMBER AT 2 PM Shapero Modern 32 St George Street London W1S 2EA 24 november: 2 pm - 6 pm 25 november: 11 am - 5 pm 26 november: 9 am - 6 pm THIS ISSUE WELCOME RUSSIAN WORKS ON PAPER By Natasha Butterwick ..................................3 1920’s-1930’s ............................................. 12 AUCTION HIGHLIGHTS FEATURED EVENTS ...........................14 By Simon Hewitt ............................................ 4 RUSSIAN TREASURES IN THE AUCTION SALES ROYAL COLLECTION Christie's, Sotheby's ........................................8 Interview with Caroline de Guitaut ............... 24 For more information please contact MacDougall's, Bonhams .................................9 Martin Hans Borg on +45 8818 1128 Bruun Rasmussen, Roseberys ........................10 RA+C RECOMMENDS .....................30 or [email protected] Stockholms Auktionsverk ................................11 PARTNERS ...............................................32 Above: Georgy Rublev, Anti-capitalist picture "Demonstration", 1932. Tempera on paper, 30 x 38 cm COPENHAGEN, DENMARK TEL +45 8818 1111 Cover: Laurits Regner Tuxen, The Marriage of Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia, 26th November 1894, 1896 BRUUN-RASMUSSEN.COM Credit: Royal Collection Trust/ © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018 russian art week guide_1018_150x180_engelsk.indd 1 11/10/2018 14.02 INTRODUCTION WELCOME Russian Art Week, yet again, strong collection of 19th century Russian provides the necessary Art featuring first-class work by Makovsky cultural bridge between and Pokhitonov, whilst MacDougall's, who Russia and the West at a time continue to provide our organisation with of even worsening relations fantastic support, have a large array of between the two. -

The Pall Mall Collection

The Pall Mall ColleCTion st. james’s London sW1 The Pall Mall ColleCTion 42 paLL maLL st. james’s London sW1 qualiTy living a stunning collection of three Luxury Lateral apartments and one exclusive penthouse the wide open spaces of st. james’s park and Green park are a short walk away. Beyond that are Knightsbridge and Chelsea with the renowned department stores of Harrods and Harvey nichols. to the north is mayfair with it’s fantastic restaurants and private member clubs together with the famous retail haven of Bond street. to the east and within easy walking distance are the famous theatres and cinemas of Haymarket and Leicester square. I6I the pall mall collectIon ST. JaMeS’S Park ST. JaMeS’S PaLaCe raC CLUB THe rITZ HoTeL HYDe Park TraFaLGar SQUare BUCkInGHaM PaLaCe Green Park the pall mall collection MaYFaIr ST. JaMeS’S SQUare I8I THe PaLL MaLL CoLLeCTIon The World’s Capital a unique mix of heritage, culture, business, fashion and fascinating architecture, makes London one of the most cosmopolitan and dynamic cities – truly a world’s capital. I10I the pall mall collectIon a hisTory of sT. jaMes’s 1600s 1690s - 1770s 1828 1960s st. james’s street is laid out. establishment of coffee and chocolate houses Building of Carlton House terrace within the modern office developments built in st. james’s principally in st. james’s street. many evolved grounds of the former Carlton House, designed street and elsewhere, including the economist into fashionable clubs such as Whites, the Cocoa by john nash Building (1964). 1661 tree and Boodles. -

Artists` Picture Rooms in Eighteenth-Century Bath

ARTISTS' PICTURE ROOMS IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY BATH Susan Legouix Sloman In May 1775 David Garrick described to Hannah More the sense of well being he experienced in Bath: 'I do this, & do that, & do Nothing, & I go here and go there and go nowhere-Such is ye life of Bath & such the Effects of this place upon me-I forget my Cares, & my large family in London, & Every thing ... '. 1 The visitor to Bath in the second half of the eighteenth century had very few decisions to make once he was safely installed in his lodgings. A well-established pattern of bathing, drinking spa water, worship, concert and theatre-going and balls meant that in the early and later parts of each day he was likely to be fully occupied. However he was free to decide how to spend the daylight hours between around lOam when the company generally left the Pump Room and 3pm when most people retired to their lodgings to dine. Contemporary diaries and journals suggest that favourite daytime pursuits included walking on the parades, carriage excursions, visiting libraries (which were usually also bookshops), milliners, toy shops, jewellers and artists' showrooms and of course, sitting for a portrait. At least 160 artists spent some time working in Bath in the eighteenth century,2 a statistic which indicates that sitting for a portrait was indeed one of the most popular activities. Although he did not specifically have Bath in mind, Thomas Bardwell noted in 1756, 'It is well known, that no Nation in the World delights so much in Face-painting, or gives so generous Encouragement to it as our own'.3 In 1760 the Bath writer Daniel Webb noted 'the extraordinary passion which the English have for portraits'.4 Andre Rouquet in his survey of The Present State of the Arts in England of 1755 described how 'Every portrait painter in England has a room to shew his pictures, separate from that in which he works. -

St James Conservation Area Audit

ST JAMES’S 17 CONSERVATION AREA AUDIT AREA CONSERVATION Document Title: St James Conservation Area Audit Status: Adopted Supplementary Planning Guidance Document ID No.: 2471 This report is based on a draft prepared by B D P. Following a consultation programme undertaken by the council it was adopted as Supplementary Planning Guidance by the Cabinet Member for City Development on 27 November 2002. Published December 2002 © Westminster City Council Department of Planning & Transportation, Development Planning Services, City Hall, 64 Victoria Street, London SW1E 6QP www.westminster.gov.uk PREFACE Since the designation of the first conservation areas in 1967 the City Council has undertaken a comprehensive programme of conservation area designation, extensions and policy development. There are now 53 conservation areas in Westminster, covering 76% of the City. These conservation areas are the subject of detailed policies in the Unitary Development Plan and in Supplementary Planning Guidance. In addition to the basic activity of designation and the formulation of general policy, the City Council is required to undertake conservation area appraisals and to devise local policies in order to protect the unique character of each area. Although this process was first undertaken with the various designation reports, more recent national guidance (as found in Planning Policy Guidance Note 15 and the English Heritage Conservation Area Practice and Conservation Area Appraisal documents) requires detailed appraisals of each conservation area in the form of formally approved and published documents. This enhanced process involves the review of original designation procedures and boundaries; analysis of historical development; identification of all listed buildings and those unlisted buildings making a positive contribution to an area; and the identification and description of key townscape features, including street patterns, trees, open spaces and building types. -

The Life of William Ewart Gladstone (Vol 2 of 3) by John Morley

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Life of William Ewart Gladstone (Vol 2 of 3) by John Morley This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Life of William Ewart Gladstone (Vol 2 of 3) Author: John Morley Release Date: May 24, 2010, 2009 [Ebook 32510] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE LIFE OF WILLIAM EWART GLADSTONE (VOL 2 OF 3)*** The Life Of William Ewart Gladstone By John Morley In Three Volumes—Vol. II. (1859-1880) Toronto George N. Morang & Company, Limited Copyright, 1903 By The Macmillan Company Contents Book V. 1859-1868 . .2 Chapter I. The Italian Revolution. (1859-1860) . .2 Chapter II. The Great Budget. (1860-1861) . 21 Chapter III. Battle For Economy. (1860-1862) . 49 Chapter IV. The Spirit Of Gladstonian Finance. (1859- 1866) . 62 Chapter V. American Civil War. (1861-1863) . 79 Chapter VI. Death Of Friends—Days At Balmoral. (1861-1884) . 99 Chapter VII. Garibaldi—Denmark. (1864) . 121 Chapter VIII. Advance In Public Position And Other- wise. (1864) . 137 Chapter IX. Defeat At Oxford—Death Of Lord Palmer- ston—Parliamentary Leadership. (1865) . 156 Chapter X. Matters Ecclesiastical. (1864-1868) . 179 Chapter XI. Popular Estimates. (1868) . 192 Chapter XII. Letters. (1859-1868) . 203 Chapter XIII. Reform. (1866) . 223 Chapter XIV. The Struggle For Household Suffrage. (1867) . 250 Chapter XV. -

The Dispersal and Formation of Sir Thomas Lawrence's Collection

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-55133-5 - The Drawings of Michelangelo and his Followers in the Ashmolean Museum Paul Joannides Excerpt More information the dispersal and formation of sir thomas lawrence’s collection of drawings by michelangelo i. the dispersal from Michelangelo apart – in its essentials has not changed since 1846, although one sheet of drawings hitherto In 1846 the University of Oxford acquired, through the placed in the Raphael school is here included as a copy generosity of a number of benefactors but supremely that after Michelangelo – an identification, indeed, made in of Lord Eldon, a large number of drawings by, attributed 1830 but subsequently overlooked.5 to, or associated with Michelangelo and Raphael. Put The two series that came to Oxford were the remains on display in the University Galleries were fifty-three of two much larger series of drawings, both owned by mountings of drawings associated with Michelangelo, and the man who has clear claim to be the greatest of all 137 by Raphael.1 Some of these mountings comprised English collectors of Old Master Drawings: Sir Thomas two or more drawings and the overall total of individual Lawrence. It is Lawrence’s collection that provided all drawings was somewhat larger.2 This exhibition and – the drawings by, and most of those after, Michelangelo consequently – its catalogue included most, but not the now in the Ashmolean Museum. Lawrence, himself a totality, of the drawings by these artists offered for sale fine draughtsman, whose precision and skill in this area -

London 252 High Holborn

rosewood london 252 high holborn. london. wc1v 7en. united kingdom t +44 2o7 781 8888 rosewoodhotels.com/london london map concierge tips sir john soane’s museum 13 Lincoln's Inn Fields WC2A 3BP Walk: 4min One of London’s most historic museums, featuring a quirky range of antiques and works of art, all collected by the renowned architect Sir John Soane. the old curiosity shop 13-14 Portsmouth Street WC2A 2ES Walk: 2min London’s oldest shop, built in the sixteenth century, inspired Charles Dickens’ novel The Old Curiosity Shop. lamb’s conduit street WC1N 3NG Walk: 7min Avoid the crowds and head out to Lamb’s Conduit Street - a quaint thoroughfare that's fast becoming renowned for its array of eclectic boutiques. hatton garden EC1N Walk: 9min London’s most famous quarter for jewellery and the diamond trade since Medieval times - nearly 300 of the businesses in Hatton Garden are in the jewellery industry and over 55 shops represent the largest cluster of jewellery retailers in the UK. dairy art centre 7a Wakefield Street WC1N 1PG Walk: 12min A private initiative founded by art collectors Frank Cohen and Nicolai Frahm, the centre’s focus is drawing together exhibitions based on the collections of the founders as well as inviting guest curators to create unique pop-up shows. Redhill St 1 Brick Lane 16 National Gallery Augustus St Goswell Rd Walk: 45min Drive: 11min Tube: 20min Walk: 20min Drive: 6min Tube: 11min Harringtonn St New N Rd Pentonville Rd Wharf Rd Crondall St Provost St Cre Murray Grove mer St Stanhope St Amwell St 2 Buckingham -

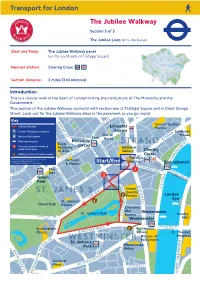

The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5

Transport for London. The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5. The Jubilee Loop (anti-clockwise). Start and finish: The Jubilee Walkway panel (on the south side of Trafalgar Square). Nearest station: Charing Cross . Section distance: 2 miles (3 kilometres). Introduction. This is a circular walk in the heart of London linking the institutions of The Monarchy and the Government. This section of the Jubilee Walkway connects with section one at Trafalgar Square and at Great George Street. Look out for the Jubilee Walkway discs in the pavement as you go round. Directions. This walk starts from Trafalgar Square. Did you know? Trafalgar Square was laid out in 1840 by Sir Charles Barry, architect of the new Houses of Parliament. The square, which is now a 'World Square', is a place for national rejoicing, celebrations and demonstrations. It is dominated by Nelson's Column with the 18-foot statue of Lord Nelson standing on top of the 171-foot column. It was erected in honour of his victory at Trafalgar. With Trafalgar Square behind you and keeping Canada House on the right, cross Cockspur Street and keep right. Go around the corner, passing the Ugandan High Commission to enter The Mall under the large stone Admiralty Arch - go through the right arch. Keep on the right-hand side of the broad avenue that is The Mall. Did you know? Admiralty Arch is the gateway between The Mall, which extends southwest, and Trafalgar Square to the northeast. The Mall was laid out as an avenue between 1660-1662 as part of Charles II's scheme for St James's Park. -

The Origins and Nature of Romanticism This Evening I Want To

The Origins and Nature of Romanticism This evening I want to say something about the origin and nature of romanticism. Generally speaking, it would be fair to conclude, it seems to me, that the neo-classical movement was official, conservative and in its later phases actively reactionary in the rigidity of its rules, though must qualify this by observing that early neo-classical architectural theory and practice gave birth to the modern theory of functionalism, so important for the twentieth century, and neo-classical paining in France under David gave birth to realism, so important for nineteenth century French painting. There can be no doubt that after 1815 the Romantic movement expressed the tensions and mood of the new age more profoundly than Neo-classicism. ‘To say the word Romanticism is to say modern art—that is, intimacy, spirituality, colour, aspiration towards the infinite, expressed by every means available to the arts’ wrote Baudelaire in his critical review of the Salon of 1846. ‘For me, Romanticism is the most recent, the latest expression of the beautiful’. The sources of romanticism lie outside of art itself and I shall not discuss them in detail, for they are often discussed. The rise of popular democracy, of industrialism, and of capitalism, changed utterly the artist’s relation to society. He importance of his old patrons the church, the court, the nobility declined swiftly. In the new situation the artist became an individualist forced to rely upon himself. Romanticism was the consequence of the new situation. It was not a style like Gothic or Baroque (this is important to grasp at once) not a style but as Baudelaire says ‘a mode of feeling’. -

NEW COACH PARKING FACILITY on the MALL • Tourist Coaches Coming to Buckingham Palace Will Enter the Mall Via Admiralty Arch

NEW COACH PARKING FACILITY ON THE MALL • Tourist coaches coming to Buckingham Palace will enter The Mall via Admiralty Arch. Having parked in the coach park, tourists can then take the short walk along the Mall with the magnificent view of The Queen Victoria Memorial and Buckingham Palace ahead of them – the perfect approach to one of London’s biggest tourist attractions • The Mall is the perfect location for other royal attractions including St James’s Palace and Clarence House. In addition, it is ideally situated for St James’s Park and other major attractions such as Horse Guard’s Parade, The Household Cavalry Museum, Trafalgar Square, the Churchill War Rooms and the Guards Museum and Chapel • New secure, on-line booking facility and easy • 8 coach parking bays available access/exit arrangements • Special introductory rate of £8 plus VAT** for • Open 9am – 6pm (or dusk if earlier) 2.5 hours parking including drive through Monday – Saturday* permit *subject to closure of Mall for special events/emergencies. • Available to book in 2.5 hour slots **Special introductory rate for drive through only permit of £6 plus VAT. Introductory rates will apply for the first year of operation and will then be subject for use at any time to review by The Royal Parks REGISTER AND START BOOKING NOW www.royalparks.org.uk/coachparking Y D NATIONAL ILL U D K GALLERY A S CC E I T t P E O PICCADILLY CIRCUS TRE 3.6.9.12.13.15 R F M S 10 mins walk from St James’s Park N 23.