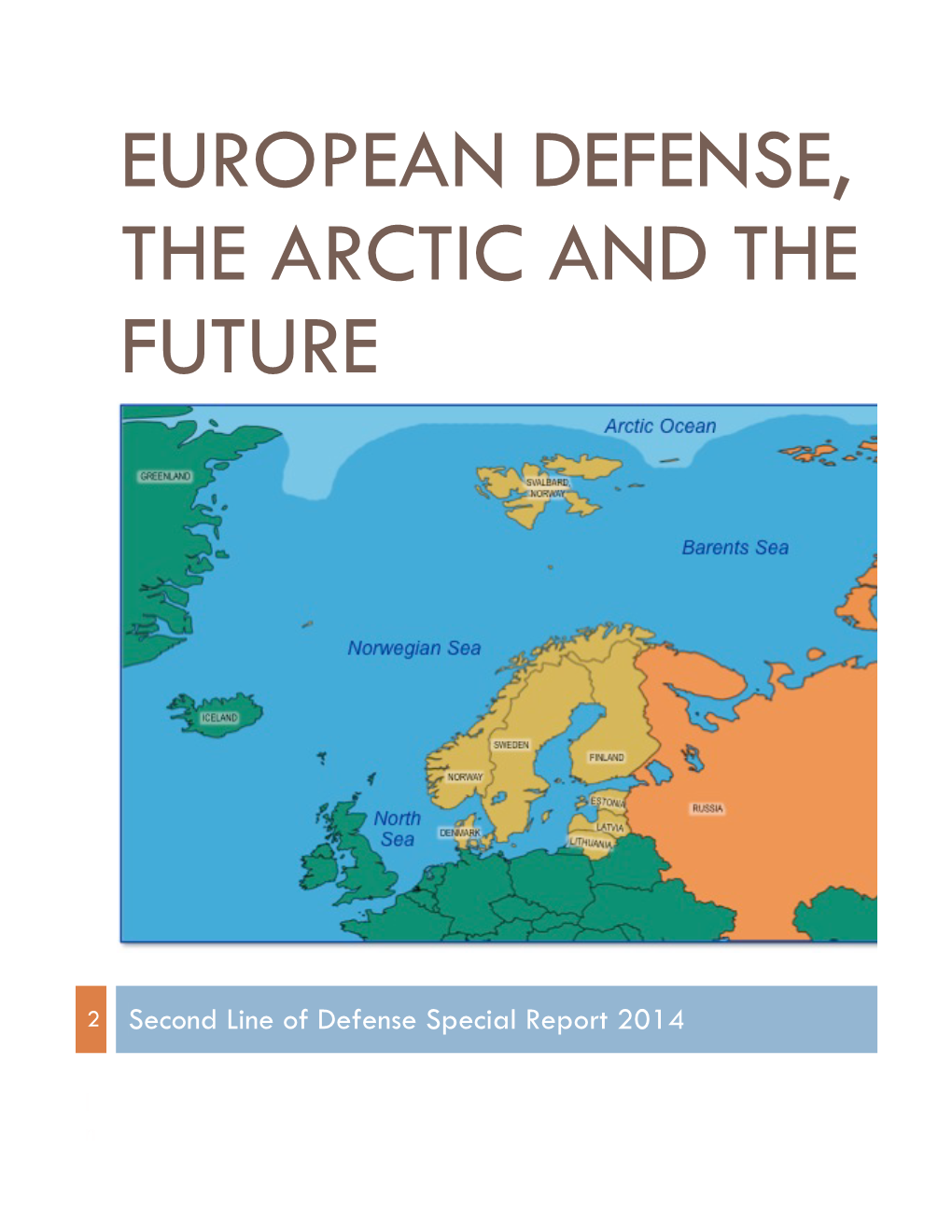

European Defense June 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EXPOSED Living with Scandal, Rumour, and Gossip

EXPOSED Living with scandal, rumour, and gossip L /� MIA-MARIE HAMMARLIN EXPOSED Living with scandal, rumour, and gossip Exposed Living with scandal, rumour, and gossip MIA-MARIE HAMMARLIN Lund University Press Copyright © Mia-Marie Hammarlin 2019 The right of Mia-Marie Hammarlin to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Lund University Press The Joint Faculties of Humanities and Theology P.O. Box 117 SE-221 00 LUND Sweden http://lunduniversitypress.lu.se Lund University Press books are published in collaboration with Manchester University Press. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library An earlier version of this book appeared in Swedish, published by Hammarlin Bokförlag in 2015 as I stormens öga ISBN 978-91-9793-812-9 ISBN 978-91-983768-3-8 hardback ISBN 978-91-983768-4-5 open access First published 2019 An electronic version of this book is also available under a Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) licence, thanks to the support of Lund University, which permits non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction provided the author(s) and Manchester University Press are fully cited and no modifications or adaptations are made. Details of the licence can be viewed at https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for any external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. -

Newsletter for the Baltics Week 47 2017

Royal Danish Embassy T. Kosciuskos 36, LT-01100 Vilnius Tel: +370 (5) 264 8768 Mob: +370 6995 7760 The Defence Attaché To Fax: +370 (5) 231 2300 Estonia, Latvia & Lithuania Newsletter for the Baltics Week 47 2017 The following information is gathered from usually reliable and open sources, mainly from the Baltic News Service (BNS), respective defence ministries press releases and websites as well as various newspapers, etc. Table of contents THE BALTICS ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Baltic States discuss how to contribute to fight against jihadists ............................................... 3 THE BALTICS AND RUSSIA .................................................................................................................. 3 Russian aircraft crossed into Estonian airspace ............................................................................ 3 NATO military aircraft last week scrambled 3 times over Russian military aircraft .................... 3 Belgian aircraft to conduct low-altitude flights in Estonian airspace .......................................... 3 Three Russian military aircraft spotted near Latvian borders ...................................................... 4 THE BALTICS AND EXERCISE .............................................................................................................. 4 Estonia’s 2nd Infantry Brigade takes part in NATO’s Arcade Fusion exercise ........................... -

2020 Fellowship Profile

2020 Fellowship Profile BY THE NUMBERS Europe DENMARK SLOVAK REPUBLIC New Returning 3 Countries 8 Countries Lieutenant Colonel Lene Lillelund Colonel Ivana Gutzelnig, MD North America Battalion Commander Director Oceania Logistics Regiment Military Centre of Aviation Medicine Ministry of Defence of the Slovak Republic CANADA Danish Army AUSTRALIA Higher Colonel Geneviève Lehoux SWITZERLAND Languages FRANCE Colonel Rebecca Talbot Education Director 9 Spoken 29 Chief of Staff Degrees Military Careers Administration Canadian Armed Forces Colonel Valérie Morcel Major General Germaine Seewer Supply Chain Branch Head Commandant, Armed Forces College Australian Defence Force 54th Signals Regiment Deputy Chief, Training and Education UNITED STATES French Army Command Swiss Armed Forces NEW ZEALAND Years of Colonel Katharine Barber GERMANY Deployments Combined Wing Commander for the Air Force UNITED KINGDOM 31 285 Group Captain Carol Abraham Service Technical Applications Center Colonel Dr. Stephanie Krause Patrick Air Force Base Florida Chief Commander Colonel Melissa Emmett Defence Strategy Management United States Air Force Medical Regiment No 1 Corps Colonel New Zealand Defence Force German Armed Forces Intelligence Corps INTERESTS Captain Rebecca Ore British Army Commander Sector Los Angeles-Long Beach o Leadership in Conflict Zones United States Coast Guard THE NETHERLANDS o Impacts of Climate and Food Insecurity on Stability Colonel Rejanne Eimers-van Nes Commander o Space Policy Personnel Logistics o Effective and Ethical Uses of AI Royal -

The History of Danish Military Aircraft Volume 1 Danish Military Aircraft Introduction

THE HISTORY OF DANISH MILITARY AIRCRAFT VOLUME 1 DANISH MILITARY AIRCRAFT INTRODUCTION This is a complete overview of all aircraft which has served with the Danish military from the first feeble start in 1912 until 2017 Contents: Volume 1: Introduction and aircraft index page 1-4 Chapter 1 - Marinens Flyvevæsen (Navy) page 5-14 Chapter 2 - Hærens Flyvertropper (Army) page 15-30 Chapter 3 – 1940-45 events page 31-36 Chapter 4 – Military aircraft production page 37-46 Chapter 5 – Flyvevåbnet (RDAF) page 47-96 Volume 2: Photo album page 101-300 In this Volume 1 Each of the five overview chapters shows a chronological list of the aircraft used, then a picture of each type in operational paintscheme as well as some special colourschemes used operationally and finally a list of each aircraft’s operational career. The material has been compiled from a multitude of sources the first of which is my research in the Danish National and Military archives, the second is material from the archives of Flyvevåbnet with which I had a fruitful cooperation in the years 1966 to 1980 and the third are the now (fortunately) many books and magasines as well as the Internet which contains information about Danish military aircraft. The pictures in Volume 1 and Volume 2-the photo album- have mainly been selected from the viewpoint of typicality and rarety and whereever possible pictures of operational aircraft in colour has been chosen. Most of the b/w picures in some way originate from the FLV historical archives, some were originally discovered there by me, whereas others have surfaced later. -

W-22 Ingrid Sahlin.Pdf

Who's homeless and whose homeless? Sahlin, Ingrid 2017 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Sahlin, I. (2017). Who's homeless and whose homeless?. Paper presented at European Network for Housing Research, Tirana, Albania. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 ENHR Tirana Sept. 4–6, 2017 (W-22) WHO’S HOMELESS AND WHOSE HOMELESS? Ingrid Sahlin School of Social Work, Lund University (Sweden) [email protected] Abstract This paper discusses what the persistent construction of ‘the homeless’ and the revitalized term ‘our homeless’ include, imply, and exclude, respectively. Departing from Simmel’s essay ‘The poor’, in which the poor is defined as the stratum that gets (or would get) public assistance, I claim that “the homeless” comprise only those to whom the society, municipalities and charities acknowledge a responsibility to give shelter. -

Norrland and Sustainable Development As Envisioned by the Ecological Modernization and Environmental Justice Discourses

Master thesis in Sustainable Development 2019/2 Examensarbete i Hållbar utveckling Sustained Asymmetries: Norrland and sustainable development as envisioned by the ecological modernization and environmental justice discourses Lisa Diehl DEPARTMENT OF EARTH SCIENCES INSTITUTIONEN FÖR GEOVETENSKAPER Master thesis in Sustainable Development 2019/2 Examensarbete i Hållbar utveckling Sustained Asymmetries: Norrland and sustainable development as envisioned by the ecological modernization and environmental justice discourses Lisa Diehl Supervisors: Annika Egan Sjölander Evaluator: Madeleine Eriksson Copyright © Lisa Diehl. Published at Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University (www.geo.uu.se), Uppsala, 2019. Contents 1. Introduction 1 1.1. Aim and research questions 3 2. Methods 4 2.1. Quantitative content analysis 4 2.2. Discourse analysis 4 2.2.1. Critical discourse analysis 5 2.3. Criticism and limitations 5 2.4. Material and selection 6 3. Theoretical framework 9 3.1. Discourse analysis and theoretical implications 9 3.2. Core-Periphery framework 9 3.3. Dependence theory 11 3.4. Sustainable development 12 3.4.1. Ecological modernization 12 3.4.2. Environmental justice 13 3.5. Previous research 13 3.5.1. Norrland in political rhetoric 13 3.5.2. Rural areas and environmental change 14 4. Results and analysis 15 4.1. In-depth analysis of land-use based industries 19 4.1.1. Norrland in general 19 4.1.2. Wind power 19 4.1.3. Forestry 21 4.1.4. Mining 22 4.1.5. Tourism 24 4.1.6. Reindeer husbandry 25 4.1.7. Hydropower 27 5. Discussion 28 5.1. Norrland and ecological modernization 28 5.2. -

Stabilization Operations Through Military Capacity Building--Integration Between Danish Conventional Forces and Special Operations Forces

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis and Dissertation Collection 2016-12 Stabilization operations through military capacity building--integration between Danish conventional forces and special operations forces Andreassen, Jesper J. D. Monterey, California: Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/51710 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA DEFENSE ANALYSIS CAPSTONE PROJECT REPORT STABILIZATION OPERATIONS THROUGH MILITARY CAPACITY BUILDING—INTEGRATION BETWEEN DANISH CONVENTIONAL FORCES AND SPECIAL OPERATIONS FORCES by Jesper J. D. Andreassen Kenneth Boesgaard Anders D. Svendsen December 2016 Capstone Project Advisor: Kalev I. Sepp Project Advisor: Anna Simons Approved for public release. Distribution is unlimited. THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704–0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington, DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED (Leave blank) December 2016 Capstone project report 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS STABILIZATION OPERATIONS THROUGH MILITARY CAPACITY BUILDING—INTEGRATION BETWEEN DANISH CONVENTIONAL FORCES AND SPECIAL OPERATIONS FORCES 6. AUTHOR(S) Jesper J. D. Andreassen, Kenneth Boesgaard, Anders D. -

Lithuania: White Paper on the Lithuanian Defence Policy

WHITE LITHUANIAN DEFENCE POLICY P A P E R MINISTRY OF NATIONAL DEFENCE VILNIUS, 2006 WHITE UDKPAPER 355(474.5) 2 Vh-05 Chief editor Kæstutis Paulauskas Translators: Giedrimas Jeglinskas, Kæstutis Paulauskas, Edmundas Èapas Photos: Alfredo Pliadþio, Egidijaus Mitkaus, Kæstuèio Dijoko, Luko Kalvaièio, Martyno Gutniko, Rièardo Uzelkos, Skomanto Pavilionio, Valentino Ðlepiko, Vytauto Palubinsko, and other photos from the archive of the Ministry of National Defence Designer Edita Namajûnienë 2006 05 29. Tiraþas 1000. Uþsakymas GL-217 Lietuvos Respublikos kraðto apsaugos ministerija Totoriø g. 25/3, LT-01121 Vilnius, www.kam.lt Maketavo KAM Leidybos ir informacinio aprûpinimo tarnyba, Totoriø g. 25/3, LT-01121 Vilnius Spausdino LK karo kartografijos centras, Muitinës g. 4, Domeikava, LT-54359 Kauno r. ISBN 9986-738-78-4 3 WHITE PAPER CONTENT Foreword ........................................................................................................................5 1. Changing Global Security Environment .....................................................................7 2. New Role and New Missions of the Armed Forces ....................................................11 3. The Main Directions of Lithuania’s Defence Policy ..................................................15 3.1. Srengthening of Euro-Atlantic Security ..................................................................16 3.2. Projection of Stability ..........................................................................................19 3.3. International Defence -

Swedens-Geopolitical-Case-Against

SWEDEN’S GEOPOLITICAL CASE AGAINST ASSANGE 2010-2019 By Prof. Marcello Ferrada de Noli. Published by Libertarian Books - Sweden. December 2019. Edition updated 11 January 2020. ISBN 978-91-88747-13-6 online edition ISBN 978-91-88747-14-3 paperback edition Cover: Artwork by Arte de Noli (Bergamo, Italy), using a background photo, unidentified author, downloaded in the Internet. Previously reproduced in the Indicter Magazine. @ 2019 Marcello Ferrada de Noli @ 2019 Libertarian Books – Sweden SWEDEN’S GEOPOLITICAL CASE AGAINST ASSANGE 2010-2019 By Marcello Ferrada de Noli LIBERTARIAN BOOKS – Sweden Science, Culture, & Human Rights Libertarianbooks.eu Author’s note: Although this book refers to events of the case arisen 2010-2019, a main coverage of the episodes 2010-2014 is given in my previous book SWEDEN VS. ASSANGE. HUMAN RIGTS ISSUES. (PDF and paperback, 342 pages): Alternative download links for the above book (PDF, 11.2 MB): Libertarianbooks.eu L’Essistenza Sweden’s Geopolitical Case Against Assange 2010-2019 – Marcello Ferrada de Noli CONTENTS FOREWORD ......................................................................................................... 11 INTRODUCTION. SWEDISH GEOPOLITICS AND THE ASSANGE CASE. ........ 17 Summary ..................................................................................................... 18 The real case against Assange .................................................................... 22 Why Sweden? ............................................................................................. -

CHRONICLE 05.Qxp

[Commentary] Presenting the first copy of the 2007 KFOR Booklet to COMKFOR Dear friends, After eleven enjoyable and work-loaded months in Kosovo it's time for me to say "Good bye". As Chief Internal Information and Editor in Chief of your "KFOR Chronicle" magazine, I leave you with sorrow. I want to personally thank COMKFOR General Kather, to CPIO Col. Knop and all members of the "PIO-family"; it was a great pleasure for me working with such an experienced team. I express my special thanks to my "KFOR Chronicle" team - Cheryl, Armend and Ihor - for all your efforts! I know together we achieved a lot. Working in PIO was an exciting task with many challenges but I also gained a lot of invaluable experiences. I really enjoyed working in KFOR, I love the international environment and the beautiful country of Kosovo. Now I'm looking forward seeing my partner, family and friends at home with a lot of positive feelings and memories of my mission here. I wish you all a safe tour in Kosovo and a good time back home! Have fun! Best wishes, Major Alexander Unterweger Commander KFOR: The KFOR Chronicle is Nations within KFOR: KFOR CHRONICLE Lt. Gen. Roland Kather, DE Army produced and fully funded by HQ HQ KFOR MNTF (S) KFOR. It is published for KFOR Argentina Germany Chief Public Information: forces in the area of responsibility. Estonia Austria Col. Michael Knop, DE Army The contents are not necessarily Hungary Azerbaijan the official views of, or endorsed Netherlands Bulgaria Chief Internal Information by, the coalition governments’ Norway Georgia & Editor in Chief: Portugal Switzerland Maj. -

Sweden Manual

Communicating Europe: Sweden Manual Information and contacts on the Swedish debate on EU enlargement in the Western Balkans Supported by the Strategic Programme Fund of the UK Foreign & Commonwealth Office 2 Communicating Europe: Sweden Manual ABOUT THIS MANUAL Who shapes the debate on the future of EU enlargement in Sweden today as the country takes over the EU Presidency in July 2009? This manual aims to provide an overview by introducing the key people and key institutions. It starts with a summary of core facts about Sweden. It looks at the packed timetable of the Swedish EU Presidency and the many issues on its agenda – including EU enlargement and visa liberalisation for the Western Balkan states. As background to one of the most intensive EU presidencies in recent years the manual describes the Swedish scene; the most important interest groups, the key government institutions, the current government, parliament and the main political parties and the key think-tanks. It looks at the country‟s mix of economic liberalism and welfare policies. It offers an overview of the policy debates on the EU, on future enlargement and the Western Balkans. Space is also given to the media landscape; TV, radio and print media and the internet-based media. As the British academic Timothy Garton Ash has recently written: “Talking here to a leading figure in the upcoming Swedish presidency of the EU, one understands what a hectic circus it will be in the last few months of 2009.” Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt has commented on the government‟s intensive presidency planning: “Sometimes things turn out like the John Lennon song: „Life is what happens to you while you are busy making other plans‟.” The prime minister added: “Planning is important, but things seldom turn out the way you intended.” Any debate in a vibrant democracy is characterised by a range of views. -

Jakob Löndahl

List of publications, Jakob Löndahl Four children aged 4-12 yrs. Parental leave for in total more than three years during 2007-2020. Summary: 51 accepted peer-reviewed original articles in international scientific journals (8 as first author, 14 as last), 157 peer-reviewed abstracts at international conferences, 5 chapters in books or reports, 1 accepted patent, 8 comprehensive computer programs (LabVIEW), >40 popular science articles both nationally and internationally, blog writer about science for Forskning&Framsteg. In total 77 talks: 35 invited research talks at conferences and meetings, 12 invited popular science talks, 25 oral presentations at international scientific conferences and 6 times invited as lecturer on PhD courses outside Sweden. ORCID: 0000-0001-9379-592X Author identifier: B-8217-2014 (Londahl, J) Doctoral Thesis, Löndahl, J., 2009. Experimental Determination of the Deposition of Aerosol Particles in the Human Respiratory Tract. Lund University. ISBN 978-91-628-7702-6 Licentiate dissertation, Löndahl, J. 2006. Health-related aerosol particle studies – respiratory tract deposition and indoor source identification. Doc: LUTFD2/(TFKF-3099)/1-35/2006 Peer-reviewed articles in international journals 51) Alsved, M., Widell, A., Dahlin, H., Karlson, S., Medstrand, P., Löndahl, J. (2020), “Aerosolization and Recovery of Viable Murine Norovirus in an Experimental Setup”, accepted for publication in Scientific Reports 50) Alsved, M., Matamis, A., Bohlin, R., Richter, M., Bengtsson, P-E, Fraenkel, C-J, Medstrand, P., Löndahl, J., (2020), “Exhaled respiratory particles during singing and talking”, accepted for publication in Aerosol Science and Technology 49) Hussein, T., Alameer, A., Jaghbeir, O., Albeitshaweesh, K., Malkawi, M., Boor, B.E., Koivisto, A.J., Löndahl, J., Alrifai, O., Al-Hunaiti, A., (2020) “Indoor Particulate Matter and Gaseous Pollutant Exposure levels inside Middle Eastern Microenvironments”, Atmosphere, 11:41 48) Alsved, M., Bourouiba, L., Duchaine, C., Löndahl, J., Marr, L.C., Parker, S.T., Prussin II, A.J., Thomas, R.J.