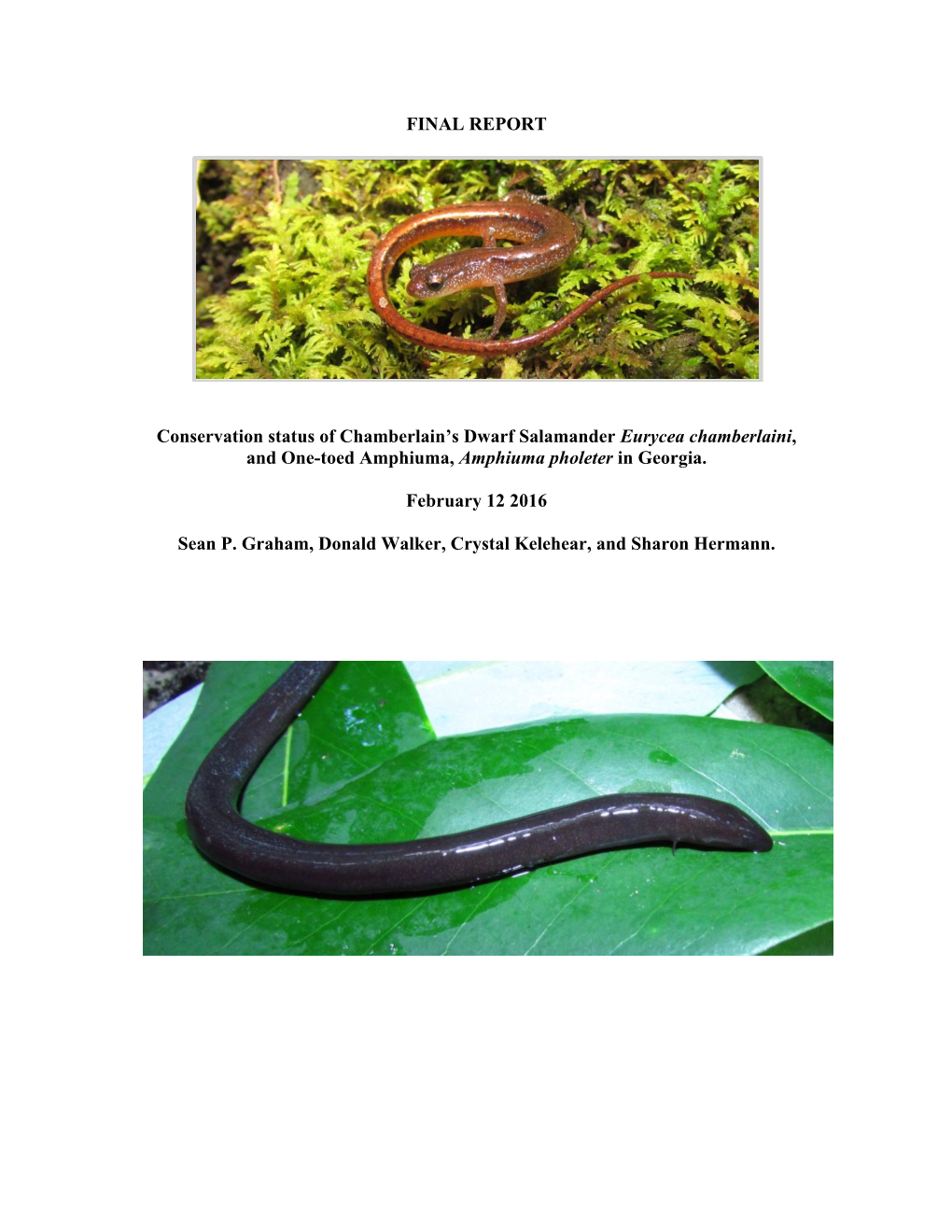

Conservation Status of Chamberlain's Dwarf Salamander and One-Toed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Limb Chondrogenesis of the Seepage Salamander, Desmognathus Aeneus (Amphibia: Plethodontidae)

JOURNAL OF MORPHOLOGY 265:87–101 (2005) Limb Chondrogenesis of the Seepage Salamander, Desmognathus aeneus (Amphibia: Plethodontidae) R. Adam Franssen,1 Sharyn Marks,2 David Wake,3 and Neil Shubin1* 1University of Chicago, Department of Organismal Biology and Anatomy, Chicago, Illinois 60637 2Humboldt State University, Department of Biological Sciences, Arcata, California 95521 3University of California, Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, Department of Integrative Biology, Berkeley, California 94720 ABSTRACT Salamanders are infrequently mentioned in referred to two amniote model systems (Gallus, analyses of tetrapod limb formation, as their development chicken; Mus, mouse), on which most research has varies considerably from that of amniotes. However, focused. However, the differences between urodeles urodeles provide an opportunity to study how limb ontog- and amniotes are so great that it has been proposed eny varies with major differences in life history. Here we assess limb development in Desmognathus aeneus,a that the vertebrate limb may have evolved twice direct-developing salamander, and compare it to patterns (Holmgren, 1933; Jarvik, 1965). Further, the differ- seen in salamanders with larval stages (e.g., Ambystoma ences between urodeles and anurans are significant mexicanum). Both modes of development result in a limb enough to have suggested polyphyly within amphib- that is morphologically indistinct from an amniote limb. ians (Holmgren, 1933; Nieuwkoop and Sutasurya, Developmental series of A. mexicanum and D. aeneus were 1976; Jarvik, 1965; reviewed by Hanken, 1986). Re- investigated using Type II collagen immunochemistry, Al- searchers have studied salamander morphology cian Blue staining, and whole-mount TUNEL staining. In (e.g., Schmalhausen, 1915; Holmgren, 1933, 1939, A. mexicanum, as each digit bud extends from the limb 1942; Hinchliffe and Griffiths, 1986), described the palette Type II collagen and proteoglycan secretion occur patterns of amphibian limb development with refer- almost simultaneously with mesenchyme condensation. -

2020 Mississippi Bird EA

ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT Managing Damage and Threats of Damage Caused by Birds in the State of Mississippi Prepared by United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Wildlife Services In Cooperation with: The Tennessee Valley Authority January 2020 i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Wildlife is an important public resource that can provide economic, recreational, emotional, and esthetic benefits to many people. However, wildlife can cause damage to agricultural resources, natural resources, property, and threaten human safety. When people experience damage caused by wildlife or when wildlife threatens to cause damage, people may seek assistance from other entities. The United States Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, Wildlife Services (WS) program is the lead federal agency responsible for managing conflicts between people and wildlife. Therefore, people experiencing damage or threats of damage associated with wildlife could seek assistance from WS. In Mississippi, WS has and continues to receive requests for assistance to reduce and prevent damage associated with several bird species. The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) requires federal agencies to incorporate environmental planning into federal agency actions and decision-making processes. Therefore, if WS provided assistance by conducting activities to manage damage caused by bird species, those activities would be a federal action requiring compliance with the NEPA. The NEPA requires federal agencies to have available -

Revision of the Eurycea Quadridigitata

Revision of the Eurycea quadridigitata (Holbrook 1842) Complex of Dwarf Salamanders (Caudata: Plethodontidae: Hemidactyliinae) with a Description of Two New Species Author(s): Kenneth P. Wray, D. Bruce Means, and Scott J. Steppan Source: Herpetological Monographs, 31(1):18-46. Published By: The Herpetologists' League DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1655/HERPMONOGRAPHS-D-16-00011 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1655/HERPMONOGRAPHS-D-16-00011 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Herpetological Monographs, 31, 2017, 18–46 Ó 2017 by The Herpetologists’ League, Inc. Revision of the Eurycea quadridigitata (Holbrook 1842) Complex of Dwarf Salamanders (Caudata: Plethodontidae: Hemidactyliinae) with a Description of Two New Species 1,3 1,2 1 KENNETH P. WRAY ,D.BRUCE MEANS , AND SCOTT J. STEPPAN 1 Department of Biological Science, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306-4295, USA 2 Coastal Plains Institute and Land Conservancy, 1313 Milton Street, Tallahassee, FL 32303-5512, USA ABSTRACT: The Eurycea quadridigitata complex is currently composed of the nominate species and E. -

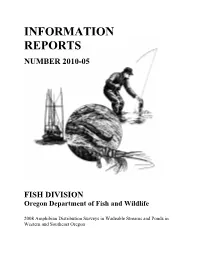

2008 Amphibian Distribution Surveys in Wadeable Streams and Ponds in Western and Southeast Oregon

INFORMATION REPORTS NUMBER 2010-05 FISH DIVISION Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife 2008 Amphibian Distribution Surveys in Wadeable Streams and Ponds in Western and Southeast Oregon Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife prohibits discrimination in all of its programs and services on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, sex or disability. If you believe that you have been discriminated against as described above in any program, activity, or facility, or if you desire further information, please contact ADA Coordinator, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, 3406 Cherry Drive NE, Salem, OR, 503-947-6000. This material will be furnished in alternate format for people with disabilities if needed. Please call 541-757-4263 to request 2008 Amphibian Distribution Surveys in Wadeable Streams and Ponds in Western and Southeast Oregon Sharon E. Tippery Brian L. Bangs Kim K. Jones Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Corvallis, OR November, 2010 This project was financed with funds administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service State Wildlife Grants under contract T-17-1 and the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, Oregon Plan for Salmon and Watersheds. Citation: Tippery, S. E., B. L Bangs and K. K. Jones. 2010. 2008 Amphibian Distribution Surveys in Wadeable Streams and Ponds in Western and Southeast Oregon. Information Report 2010-05, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, Corvallis. CONTENTS FIGURES....................................................................................................................................... -

Comparative Osteology and Evolution of the Lungless Salamanders, Family Plethodontidae David B

COMPARATIVE OSTEOLOGY AND EVOLUTION OF THE LUNGLESS SALAMANDERS, FAMILY PLETHODONTIDAE DAVID B. WAKE1 ABSTRACT: Lungless salamanders of the family Plethodontidae comprise the largest and most diverse group of tailed amphibians. An evolutionary morphological approach has been employed to elucidate evolutionary rela tionships, patterns and trends within the family. Comparative osteology has been emphasized and skeletons of all twenty-three genera and three-fourths of the one hundred eighty-three species have been studied. A detailed osteological analysis includes consideration of the evolution of each element as well as the functional unit of which it is a part. Functional and developmental aspects are stressed. A new classification is suggested, based on osteological and other char acters. The subfamily Desmognathinae includes the genera Desmognathus, Leurognathus, and Phaeognathus. Members of the subfamily Plethodontinae are placed in three tribes. The tribe Hemidactyliini includes the genera Gyri nophilus, Pseudotriton, Stereochilus, Eurycea, Typhlomolge, and Hemidac tylium. The genera Plethodon, Aneides, and Ensatina comprise the tribe Pleth odontini. The highly diversified tribe Bolitoglossini includes three super genera. The supergenera Hydromantes and Batrachoseps include the nominal genera only. The supergenus Bolitoglossa includes Bolitoglossa, Oedipina, Pseudoeurycea, Chiropterotriton, Parvimolge, Lineatriton, and Thorius. Manculus is considered to be congeneric with Eurycea, and Magnadig ita is congeneric with Bolitoglossa. Two species are assigned to Typhlomolge, which is recognized as a genus distinct from Eurycea. No. new information is available concerning Haptoglossa. Recognition of a family Desmognathidae is rejected. All genera are defined and suprageneric groupings are defined and char acterized. Range maps are presented for all genera. Relationships of all genera are discussed. -

Vernacular Name AMPHIUMA, ONE-TOED (Aka: Congo Eel, Congo Snake, Ditch Eel, Fish Eel and Lamprey Eel)

1/6 Vernacular Name AMPHIUMA, ONE-TOED (aka: Congo Eel, Congo Snake, Ditch Eel, Fish Eel and Lamprey Eel) GEOGRAPHIC RANGE Eastern Gulf coast. HABITAT Wetlands: slow moving or stagnant freshwater rivers/streams/creeks and bogs, marshes, swamps, fens and peat lands. CONSERVATION STATUS IUCN: Near Threatened (2016). Population Trend: Decreasing. Because of the limited extent of its occurrence and because of the declining extent and quality of its habitat, this species is close to qualifying for Vulnerable. COOL FACTS Amphiumas are commonly known as "Congo eels," a misnomer. First of all, amphiumas are amphibians, rather than fish (which eels are). This notwithstanding, amphiumas bear resemblance to the elongate fishes. It is easy to overlook the diminutive legs, and the lack of any external gills adds to the similarity between the amphiumas and eels. Amphiumas are adapted for digging and tunneling. They seem to spend most of the time in muddy burrows and are rarely observed in the wild. They never fully metamorphose and retain larval characteristics in varying degrees into adulthood: one pair of the larval gill slits is retained and never disappears, no eyelids, no tongue and the presence of 4 gill arches with a single respiratory opening between the 3 rd--4th arches. Amphiumas have two pairs of limbs, and the three species, all of which occur in the S.E. U.S, differ in regard to the number of toes at the ends of these limbs: one, two or three. These amphiumas possess tiny, single-toed limbs, one pair just behind the small gill opening at each side of the neck and another pair just ahead of the longitudinal anal slit . -

1 Southeastern Us Coastal Plain

1 In Press: 2000. Chapter XX. Pages __-__ in Richard C. Bruce, Robert J. Jaeger, and Lynn D. Houck, editors. The Biology of the Plethodontidae. Plenum Publishing Corp., New York, N. Y. SOUTHEASTERN U. S. COASTAL PLAIN HABITATS OF THE PLETHODONTIDAE: THE IMPORTANCE OF RELIEF, RAVINES, AND SEEPAGE D. BRUCE MEANS Coastal Plains Institute and Land Conservancy, 1313 N. Duval Street, Tallahassee, FL 32303, USA 1. INTRODUCTION Because the Coastal Plain is geologically and biologically a very distinct region of the southeastern United States -- the southern portion having a nearly subtropical climate -- the life cycles, ecology, and evolutionary relationships of its plethodontid salamanders may be significantly different from plethodontids in the Appalachians and Piedmont. Little attention has been paid, however, to Coastal Plain plethodontids. For instance, of the 133 scientific papers and posters presented at the four plethodontid salamander conferences held in Highlands, North Carolina, since 1972, only three (2%) dealt with Coastal Plain plethodontids. And yet, while it possesses fewer total species than the Appalachians and Piedmont, the Coastal Plain boasts of slightly more plethodontid diversity at the generic level. The genera Phaeognathus, Haideotriton, and Stereochilus are Coastal Plain endemics, whereas in the Appalachians and Piedmont Gyrinophilus is the only endemic genus unless one accepts Leurognathus apart from Desmognathus. In addition, Aneides is found in the Appalachians and not the Coastal Plain, but the genus also occurs in the western U. S. All the rest of the plethodontid genera east of the Mississippi River are shared by the Coastal Plain with the Appalachians and Piedmont. Geographically, the Coastal Plain includes Long Island in New York, and stretches south from the New Jersey Pine Barrens to include all of Florida, then west to Texas (Fig. -

Chassahowitzka Chassahowitzka Plan Comprehensive Conservation

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Chassahowitzka NationalWildlifeRefuge Chassahowitzka National Wildlife Refuge Refuge Manager: Michael Lusk, (Project Leader) 1502 S.E. Kings Bay Drive Crystal River, FL 34429 Phone: (352) 563-2088 / ext. 202 Fax: (352) 795-7961 E-mail: [email protected] U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service 1 800/344 WILD http://www.fws.gov Chassahowitzka National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive ConservationPlan September 2012 Comprehensive Conservation Plan USFWS Photos Photo Credits: Operation Migration, by Keith Ramos Dog Island, by Amber Breland Chass Aerial, by Joyce Kleen Comprehensive Conservation Plans provide long-term guidance for manage- ment decisions; set forth goals, objectives, and strategies needed to accom- plish refuge purposes; and identify the Fish and Wildlife Service’s best esti- mate of future needs. These plans detail program planning levels that are sometimes substantially above current budget allocations and, as such, are primarily for Service strategic planning and program prioritization purposes. The plans do not constitute a commitment for staffing increases, operational and maintenance increases, or funding for future land acquisition. Chassahowitzka National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region September 2012 COMPREHENSIVE CONSERVATION PLAN CHASSAHOWITZKA NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE Citrus and Hernando Counties, Florida U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia September -

AMPHIBIANS of OHIO F I E L D G U I D E DIVISION of WILDLIFE INTRODUCTION

AMPHIBIANS OF OHIO f i e l d g u i d e DIVISION OF WILDLIFE INTRODUCTION Amphibians are typically shy, secre- Unlike reptiles, their skin is not scaly. Amphibian eggs must remain moist if tive animals. While a few amphibians Nor do they have claws on their toes. they are to hatch. The eggs do not have are relatively large, most are small, deli- Most amphibians prefer to come out at shells but rather are covered with a jelly- cately attractive, and brightly colored. night. like substance. Amphibians lay eggs sin- That some of these more vulnerable spe- gly, in masses, or in strings in the water The young undergo what is known cies survive at all is cause for wonder. or in some other moist place. as metamorphosis. They pass through Nearly 200 million years ago, amphib- a larval, usually aquatic, stage before As with all Ohio wildlife, the only ians were the first creatures to emerge drastically changing form and becoming real threat to their continued existence from the seas to begin life on land. The adults. is habitat degradation and destruction. term amphibian comes from the Greek Only by conserving suitable habitat to- Ohio is fortunate in having many spe- amphi, which means dual, and bios, day will we enable future generations to cies of amphibians. Although generally meaning life. While it is true that many study and enjoy Ohio’s amphibians. inconspicuous most of the year, during amphibians live a double life — spend- the breeding season, especially follow- ing part of their lives in water and the ing a warm, early spring rain, amphib- rest on land — some never go into the ians appear in great numbers seemingly water and others never leave it. -

Distribution and Conservation Genetics of the Cow Knob Salamander, Plethodon Punctatus Highton (Caudata: Plethodontidae)

Distribution and Conservation Genetics of the Cow Knob Salamander, Plethodon punctatus Highton (Caudata: Plethodontidae) Thesis submitted to The Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree Master of Science Biological Sciences by Matthew R. Graham Thomas K. Pauley, Committee Chairman Victor Fet, Committee Member Guo-Zhang Zhu, Committee Member April 29, 2007 ii Distribution and Conservation Genetics of the Cow Knob Salamander, Plethodon punctatus Highton (Caudata: Plethodontidae) MATTHEW R. GRAHAM Department of Biological Sciences, Marshall University Huntington, West Virginia 25755-2510, USA email: [email protected] Summary Being lungless, plethodontid salamanders respire through their skin and are especially sensitive to environmental disturbances. Habitat fragmentation, low abundance, extreme habitat requirements, and a narrow distribution of less than 70 miles in length, makes one such salamander, Plethodon punctatus, a species of concern (S1) in West Virginia. To better understand this sensitive species, day and night survey hikes were conducted through ideal habitat and coordinate data as well as tail tips (10 to 20 mm in length) were collected. DNA was extracted from the tail tips and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was used to amplify mitochondrial 16S rRNA gene fragments. Maximum parsimony, neighbor-joining, and UPGMA algorithms were used to produce phylogenetic haplotype trees, rooted with P. wehrlei. Based on our DNA sequence data, four disparate management units are designated. Surveys revealed new records on Jack Mountain, a disjunct population that expands the known distribution of the species 10 miles west. In addition, surveys by Flint verified a population on Nathaniel Mountain, WV and revealed new records on Elliot Knob, extending the known range several miles south. -

Herpetofaunal Communities in Ephemeral Wetlands Embedded Within Longleaf Pine Flatwoods of the Gulf Coastal Plain

20162016 SOUTHEASTERNSoutheastern NaturalistNATURALIST 15(3):431–447Vol. 15, No. 3 K.J. Erwin, H.C. Chandler, J.G. Palis, T.A. Gorman, and C.A. Haas Herpetofaunal Communities in Ephemeral Wetlands Embedded within Longleaf Pine Flatwoods of the Gulf Coastal Plain Kenneth J. Erwin1, Houston C. Chandler1,2,*, John G. Palis3, Thomas A. Gorman1,4, and Carola A. Haas1 Abstract - Ephemeral wetlands surrounded by Pinus palustris (Longleaf Pine) flatwoods support diverse herpetofaunal communities and provide important breeding habitat for many species. We sampled herpetofauna in 3 pine flatwoods wetlands on Eglin Air Force Base, Okaloosa County, FL, over 2 time periods (1 wetland [1] from 1993 to1995 and 2 wetlands [2 and 3] from 2010 to 2015) using drift fences that completely encircled each wetland. We documented 37, 46, and 43 species of amphibians and reptiles at wetlands 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Herpetofaunal communities were remarkably similar across all 3 wetlands (Sorenson Index values > 0.97) despite sampling that occurred 15–20 years apart on wetlands located approximately 10 km apart. Ambystoma bishopi (Reticulated Flat- woods Salamander), Pseudacris ornata (Ornate Chorus Frog), and Eurycea quadridigitata (Dwarf Salamander), all species of conservation concern, were captured at all 3 wetlands, indicating that these wetlands provide habitat for specialist species. Overall, habitat con- servation and management has succeeded in maintaining suitable habitat for herpetofauna in recently surveyed wetlands, despite continued range-wide threats from changes to his- toric fire regimes and climate change. Introduction Ephemeral wetlands often support diverse amphibian and reptile communities (Dodd and Cade 1998, Gibbons et al. 2006, Means et al. -

TRAPPING SUCCESS and POPULATION ANALYSIS of Siren Lacertina and Amphiuma Means

TRAPPING SUCCESS AND POPULATION ANALYSIS OF Siren lacertina AND Amphiuma means By KRISTINA SORENSEN A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2003 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank my committee members Lora Smith, Franklin Percival, and Dick Franz for all their support and advice. The Department of Interior's Student Career Experience Program and the U.S. Geological Survey's Amphibian Research and Monitoring Initiative provided funding for this project. I thank those involved with these programs who have helped me over the last three years: David Trauger, Ken Dodd, Jamie Barichivich, Jennifer Staiger, Kevin Smith, and Steve Johnson. Numerous people helped with field work: Audrey Owens, Maya Zacharow, Chris Gregory, Matt Chopp, Amanda Rice, Paul Loud, Travis Tuten, Steve Johnson, and Jennifer Staiger, Lora Smith, and the UF Wildlife Field Techniques Courses of2001-2002. Paul Moler and John Jensen provided advice and shared their wealth of herpetological knowledge. I thank the staff of Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge and Steve Coates, manager of the Ordway Preserve, for their assistance on numerous occasions and for permission to conduct research on their property. Marinela Capanu of the IFAS Statistical Consulting Unit assisted with statistical analysis. Julien Martin, Bob Dorazio, Rob Bennets, and Cathy Langtimm provided advice on population analysis. I also thank the administrative staff of the Florida Caribbean Science Center and the Florida Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit. I am much indebted to all of these people, without whom this thesis would not have been possible.