PIF) for HISTORIC DISTRICTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VMI History Fact Sheet

VIRGINIA MILITARY INSTITUTE Founded in 1839, Virginia Military Institute is the nation’s first state-supported military college. U.S. News & World Report has ranked VMI among the nation’s top undergraduate public liberal arts colleges since 2001. For 2018, Money magazine ranked VMI 14th among the top 50 small colleges in the country. VMI is part of the state-supported system of higher education in the Commonwealth of Virginia. The governor appoints the Board of Visitors, the Institute’s governing body. The superintendent is the chief executive officer. WWW.VMI.EDU HISTORY OF VIRGINIA MILITARY INSTITUTE 540-464-7230 INSTITUTE OFFICERS On Nov. 11, 1839, 23 young Virginians were history. On May 15, 1863, the Corps of mustered into the service of the state and, in Cadets escorted Jackson’s remains to his Superintendent a falling snow, the first cadet sentry – John grave in Lexington. Just before the Battle of Gen. J.H. Binford Peay III B. Strange of Scottsville, Va. – took his post. Chancellorsville, in which he died, Jackson, U.S. Army (retired) Today the duty of walking guard duty is the after surveying the field and seeing so many oldest tradition of the Institute, a tradition VMI men around him in key positions, spoke Deputy Superintendent for experienced by every cadet. the oft-quoted words: “The Institute will be Academics and Dean of Faculty Col. J.T.L. Preston, a lawyer in Lexington heard from today.” Brig. Gen. Robert W. Moreschi and one of the founders of VMI, declared With the outbreak of the war, the Cadet Virginia Militia that the Institute’s unique program would Corps trained recruits for the Confederate Deputy Superintendent for produce “fair specimens of citizen-soldiers,” Army in Richmond. -

The Institute Report

THE INSTITUTE REPORT Volume XVII October27,l989 Number 3 An occasional publication of the Public Information Office, Virginia Military Institute, Lexington, Virginia 24450. Tel (703) 464-7207. VMI to Celebrate 150th with Cake, Cannonade, and Convocation While its focus is clearly set on the 21st century, Events ofthe landmark year began last January VMI will spend the Nov. 10-12 weekend in celebration after several years of planning by a 17-member ofits 150th birthday and the accomplishments that VIRGINIA M1UTARY INSTITUTE Sesquicentennial Committee composed of Institute have marked the years since its opening on Nov. 11, wide representatives, including members ofthe Corps 1839. Hundreds ofalumni and special guests will joi n ofCadets. The committee has been headed by Col. intheculminating events ofthe sesquicentennial year. George M. Brooke, Jr., '36, of Lexington, emeritus The weekend program, which is listed in detail professor of history, with Col. Leonard L. Lewane, elsewhere is this publication, includes a three-day '50B, also of Lexington, as executive director of the schedule ofactivities beginning Friday, Nov. 10, with sesquicentennial office. burial of a time capsule, parade, and what promises The year-long anniversary events leading up to that evening to be a stirring and memorable concert. Founders Day November's grand finale have included special memorial observances; on Saturday will include the dedication ofthe new science hall; a con concerts; lectures; exhibits; a play; a leadership conference; several vocation; post-wide luncheons; and an afternoon football game. commemorative items, including a limited edition sesquicentennial Popular NBC weatherman Willard Scott has also been invited to medallion; and thepublication ofthree books. -

Snickers Gap, Loudoun County, Virginia Introduction: Snickers Gap

Snickers Gap, Loudoun County, Virginia Introduction: Snickers Gap, originally Williams Gap, is a wind gap in the Blue Ridge Mount on the border of Loudoun County and Clark County in Virginia. The gap is traversed by Virginia State Route 7. The Appalachian Trail also passes across the gap. Bear’s Den and Raven Rocks are adjacent to the gap. Geography: At 1,056 feet (322 m) the gap is approximately 300 to 600 feet (91 to 183 m) below the adjacent ridge line and 400 to 600 feet (120 to 180 m) above the surrounding countryside. Due to the dwindling height of the Blue Ridge as it approaches the Potomac River, Snickers Gap is one of the lowest wind gaps of the ridge in Virginia, with only Manassas Gap and the adjacent Keyes Gap being lower. The gap connects the northern Virginia piedmont with the lower Shenandoah Valley and serves as a main thoroughfare between the two regions. History: The gap has been a major thoroughfare since before the European colonization of the area. Native Americans originally cut a trail through the gap that continued to be used by settlers. The gap was known as Williams’ Gap until the early 1780’s, when the modern name began to be used. The gap derived its name from Edward Snickers, who owned the gap and surrounding land and operated a ferry across the Shenandoah River on the western side of the gap. But the late 18th century the Snikersville Turnpike and the Snickers Gap Turnpike were completed, and Snickers Gap became the main thoroughfare between Loudoun County and the Shenandoah bypassing Keyes Gap, which to that point had been the preferred route. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

(Rev. 10-90) NPS Farm 10-900 OMB KO. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Sewice NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominattng or requesting determinations for ind~vidualpropefiies and districts. See insmctions in How to Complete theNattonal Register ofHistor~cPlaces Registration Farm (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking"^" in the appropriate bax or by enterlng the ~nformat~onrequested. lfany item does not apply to the property beingdacumented, enter "NIP for "not applicable " For functions, architecmral classificat~an.materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the ~nstructions.Place additional entrles and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Unison Historic District other nameslsite number VDHR # 53-692 2. Location street & number Area including parts of Unison and Bloomfield roads not for publication N/A state Virginia codex county Loudoun code 107 Zip a 3. StatelFederal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this -X- nomination -request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property -X- meets -does not meet the National Register Criteria. 1 recommend that this property be considered significant -nationally -statewide _X- locally. ( See continuation i 1 Signature- of certifvi6Lofficial. -

Nomination Form Date Entered See Instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type All Entries-Complete Applicable Sections 1

NPS Form 10.800 OM6 NO. 1024-0018 -. \/LR# 1/17/g+ IJKHP- >/=/gy Exp. 30-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received Inventory-Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries-complete applicable sections 1. Name or7 6Jb\ historic BLUEMONT HISTORIC DISTRICT - (VHLC File No. &-) and or common N/A 2. Location Intersection of VA routes 734 & 760 street & number N/A not for publication city, town B1uemOnt N/Avicinity of Virginia 51 county state code code 107 3. Classification ~~~ ~ -- Category Ownership Status Present Use district -public X occupied -agriculture -museum -building(s) -private X unoccupied -Lcommercial -park -structure both -work in progress -educational 1L private residence -site Public Acquisition Accessible -entertainment 2+-religious -object -in process X yes: restricted -government -scientific -being considered X- yes: unrestricted -industrial -transportation N/A -no -military -other: . 4. Owner of Property name Multiple Owners (See Continuation Sheet 14) street & number N/A citv. town B1uemOnt N/A vicinity of state Virginia 22012 -- ~ - 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Loudoun County Clerkts Office street & number East Market Street clty, town Leesburg state Virginia 22075 6. Reoresentation in Existing Surveys Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission title Survev (F has this property been determined eligible? yes X no - :1p /+Oh-13') - - date -

Addendum No. 2

Addendum No. 2 Issue Date: 22 May 2017 To: Bidding Contractors - Plan Holders Project: Blue Ridge (Crozet) Tunnel Rehabilitation and Trail Project Nelson County Board of Supervisors The following items are being issued here for clarification, addition or deletion and have been incorporated into the Construction Documents and Project Manual, and shall be included as part of the bid documents. All Contractors shall acknowledge this Addendum No. 2 in the Bid Form. Failure of acknowledgment may result in rejection of your bid. All Bidders shall be responsible for seeing that their subcontractors are properly apprised of the contents of this addendum. BID DATE AND TIME: 1. The sign in sheet from the pre-bid meeting held on Friday May 12 th is included with Addenda 2. 2. At this time, the bid opening remains May 31 st at 2.00 PM. CLARIFICATIONS / CONTRACTOR QUESTIONS: 1. Q: The unit of measurement for the aggregate base material is in cubic yards. Can the units be revised to reflect the number of tons? A: Section 607.12 Unit Costs and Measures provides for the acceptable units for measurement. The quantity reflected in the bid form is based upon the area x thickness of the material. Please note that the volume is measured as “in-place and does not account for any volumetric loss due to compaction. The conversion from cubic yards to tons is based upon the unit weight of the material. For example, assuming a unit weight of 130 lbs/ft 3, which may be considered normal for VDOT 21B material, the conversion to tons would be 1 CY x (27 ft 3 / yd 3) x (130 lbs/ft 3) x (1 ton/2000 lbs). -

Century West Point and the Invention of the Blackboard

An Officer and a Scholar: Nineteenth-Century West Point and the Invention of the Blackboard Christopher J. Phillips Over two centuries after the invention of blackboards, they still fea- ture prominently in many American classrooms. The blackboard has outlasted most other educational innovations and technologies, and has always been more than an aide memoire. Students and teachers have long assumed inscriptions on its surface made mental processes visible. As early as 1880, in fact, the A.H. Andrews & Co. catalog described the blackboard as a “mirror reflecting the workings, character, and quality of the individual mind.”1 The blackboard’s ultimate origins are un- clear but in North America one institution, the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, played a particularly important Christopher J. Phillips is an Assistant Professor & Faculty Fellow at the NYU Gallatin School of Individualized Study and has been appointed assistant professor in Carnegie Mellon University’s Department of History. For help with the preparation of this arti- cle, he would like to especially acknowledge Michael Barany, Bruno Belhoste, Stephanie Dick, Peggy Kidwell, Fred Rickey, David Roberts, Brittany Shields, and Alma Steingart, as well as audiences at meetings of the History of Science Society and American Math- ematical Society, and the anonymous referees for History of Education Quarterly. He also wishes to thank the librarians and archivists of the United States Military Academy in West Point, New York. 1A.H. Andrews & Co., Illustrated Catalogue of School Merchandise (Chicago, IL: A.H. Andrews & Co.,1881), 73, quoted in David Tyack and Larry Cuban, Tinkering Toward Utopia: A Century of Public School Reform (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995), 121. -

Download Guidebook to Richmond

SIA RVA SOCIETY FOR INDUSTRIAL ARCHEOLOGY 47th ANNUAL CONFERENCE MAY 31 - JUNE 3, 2018 RICHMOND, VIRGINIA GUIDEBOOK TO RICHMOND SIA RVA SOCIETY FOR INDUSTRIAL ARCHEOLOGY 47th ANNUAL CONFERENCE MAY 31 - JUNE 3, 2018 RICHMOND, VIRGINIA OMNI RICHMOND HOTEL GUIDEBOOK TO RICHMOND SOCIETY FOR INDUSTRIAL ARCHEOLOGY MICHIGAN TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY 1400 TOWNSEND DRIVE HOUGHTON, MI 49931-1295 www.sia-web.org i GUIDEBOOK EDITORS Christopher H. Marston Nathan Vernon Madison LAYOUT Daniel Schneider COVER IMAGE Philip Morris Leaf Storage Ware house on Richmond’s Tobacco Row. HABS VA-849-31 Edward F. Heite, photog rapher, 1969. ii CONTENTS Acknowledgements ..................................................................................iv INTRODUCTION Richmond’s Industrial Heritage .............................................................. 3 THURSDAY, MAY 31, 2018 T1 - The University of Virginia ................................................................19 T1 - The Blue Ridge Tunnel ....................................................................22 T2 - Richmond Waterfront Walking Tour ..............................................24 T3 - The Library of Virginia .....................................................................26 FRIDAY, JUNE 1, 2018 F1 - Strickland Machine Company ........................................................27 F1 - O.K. Foundry .....................................................................................29 F1 & F2 - Tobacco Row / Philip Morris USA .......................................32 F1 & -

Backpacking Suggestions the Best Idea for a First Backpacking Trip Is A

"First" Backpacking Suggestions The best idea for a first backpacking trip is a 3-day (2-night) 15-mile trip that can be safely taken by a relatively inexperienced Venture patrol. Details need be flushed out by the patrol as they plan. The suggestions shown below are only outlines and will need to be modified based upon equipment, season, weather, experience, and physical conditioning. The Appalachian Trail (AT) is closest to DC at VA Rte. 9, Rte. 7, and Rte. 50. The crossing at I- 66/Rte 55 is quick to get to, though it's further. In the 40 miles of AT between I-66 and Rte 9, there six locations than can be used for small group overnight camping; Manassas Gap Shelter, Dick's Dome Shelter, Rod Hollow Shelter, Bear's Den Youth Hostel (fee required), Blackburn Trail Center, and David Lesser Memorial Shelter. Sky Meadows State Park, located between Rte 55 and Rte 50, makes an excellent launching point. It has a primitive camping area (fee required) that can be used for the first night or as a base camp for hikes along the AT. If you go out on Friday night, pick a campsite that is near a trailhead and easy to walk to. In the winter, you will need to get to the AT as soon as possible because of a typical Friday night late start due to school and an early sunset. Be prepared to walk in the dark. The following are some suggested section hikes along the AT. For more details and maps, purchase the Appalachian Trail Guide to Maryland, and Northern Virginia published by the Appalachian Trail Conference (ATC) and available at most backcountry equipment stores. -

HISTORIC SITE FILE: 13\AC.-K L°'-Nd \It ?Ftj R-1 ~ !);- 5Ft-;

HISTORIC SITE FILE: 13\AC.-K l°'-nd \it ?ftJ r-1~ !);-_5ft-; c r -PRINCE WILLIAM PUBLIC LIBRARY SYSTEM'l!>1=111!J=r :!. !J!J!J RELIC/Bull Run Reg Lib, Manassas, VA A LESSON IN "In my opinion, properly protected and n an area rife with American history researched. Buckland has the unique I - monuments, President's homes, potential to teach generations to come Civil War battlefields - there is one place nearby that can hold its own much about American values. especially wirh anything anybody else has to offer. the role of free enterprise, in the develop You've probably never heard of it, but if ment and growth of the U.S. during its you've lived in the area for any length founding years between the American of time, you've probably driven past Revolution and the Civil War Era. Too it hundreds of times, maybe - if you often, as at Jamestown. no architectural commute to work in Northern Virginia evidence and few documents survive to - even thousands of times. The place? help tell significant pieces of the story as It's Buckland, just over the county line it does at Buckland." in Prince William County. So, exactly what kind of history are William M. Kelso, Ph.D. we talking about here? Well, how about APVA Director of Archeology Jamestown Rediscovery Native American burial mounds to start. Then add in all the luminaries from the birth of this nation - George Washingron, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, Andrew Jackson. Toss in a couple of foreigners The landscape has not changed much from this October I8 1 1863 drawing by Alfred Waud (scene of calvary engagement with Stuart) and the Buckland Preservation like the Marquis de Lafayette and Society is working hard to keep it that way. -

Commonwealth of Virginia Geology of the Ashby Gap

COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT DIVISION OF MINERAL RESOURCES GEOLOGY OF THE ASHBY GAP QUADRANGLE, VIRGINIA THOMAS M. GATHRIGHT II AND PAUL G. NYSTROM, JR. REPORT OF INVESTIGATIONS 36 VIRGINIA DIVISION OF MINERAL RESOURCES Jqmes L. Cqlver Commissioner of Minerol Resources qnd Stote Geologist CHARLOTTESVILLE, VIRGINIA 1974 COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA DEPATTMENT OF CONSERVATION AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT DIVISION OF MINERAT RESOURCES GEOLOGY OF THE ASHBY GAP QUADRANGLE, VIRGINIA THOMAS M. GATHRIGHT II AND PAUL G. NYSTROM, JT. REPORT OF INVESTIGATIONS 36 VITGINIA DIVISION OF MINERAL RESOURCES Jomec L. Cqlver Cornmirioner of Minerol Resources ond Stqte Geologist CHAITOTTESVIILE, VNG|N|A 1974 CouuoNwn.a.r,Trr oF VmcrNrl DsrAnrxrpNr or Puncn.o,sps AND Suppl,y RTcHMoND t974 Portions of this publication may be quoted if credit is given to the Virginia Division of Mineral Resources. ft is recommended that reference to this renort be made in the following form: Gathright, T. M., II, and Nystrom, P. G., Jt.,!974, Geology of the Ashby Gap quadrangle, Virginia: Yirginia Division of Mineral Resources Rept. Inv. 36, 55 p. DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT Richmond, Virginia Mmvru M. SurnsnLAND, Director Jpnar,o F. Moonn, Deputy Director A. S. RacgAL, JB., E*ecuti,ae Assistant BOARD W'rlr,nu H. KtNc, Burkeville, Chairman Wrr,lrlu H. StlNrucnN, Falls Church, Vi,ce Chairmnn D. Hntny ALMoND, Richmond Maron T. BoNtoN, Suffolk A. R. DuNNrNc, Millwood Aoolr U. HoNr.a,Lt, Richmond J. H. JonNSoN, West Point Rosont Plrrrnsou, Charlottesville Fnnnnnrc S. Runo, Manakin-Sabot Colr,rNs SNxDEn, Accomac Fnnonmcr W. War,xun, Richmond SnrnulN WAt t AcE, Cleveland CONTENTS Abstract 1 1 Introduction . -

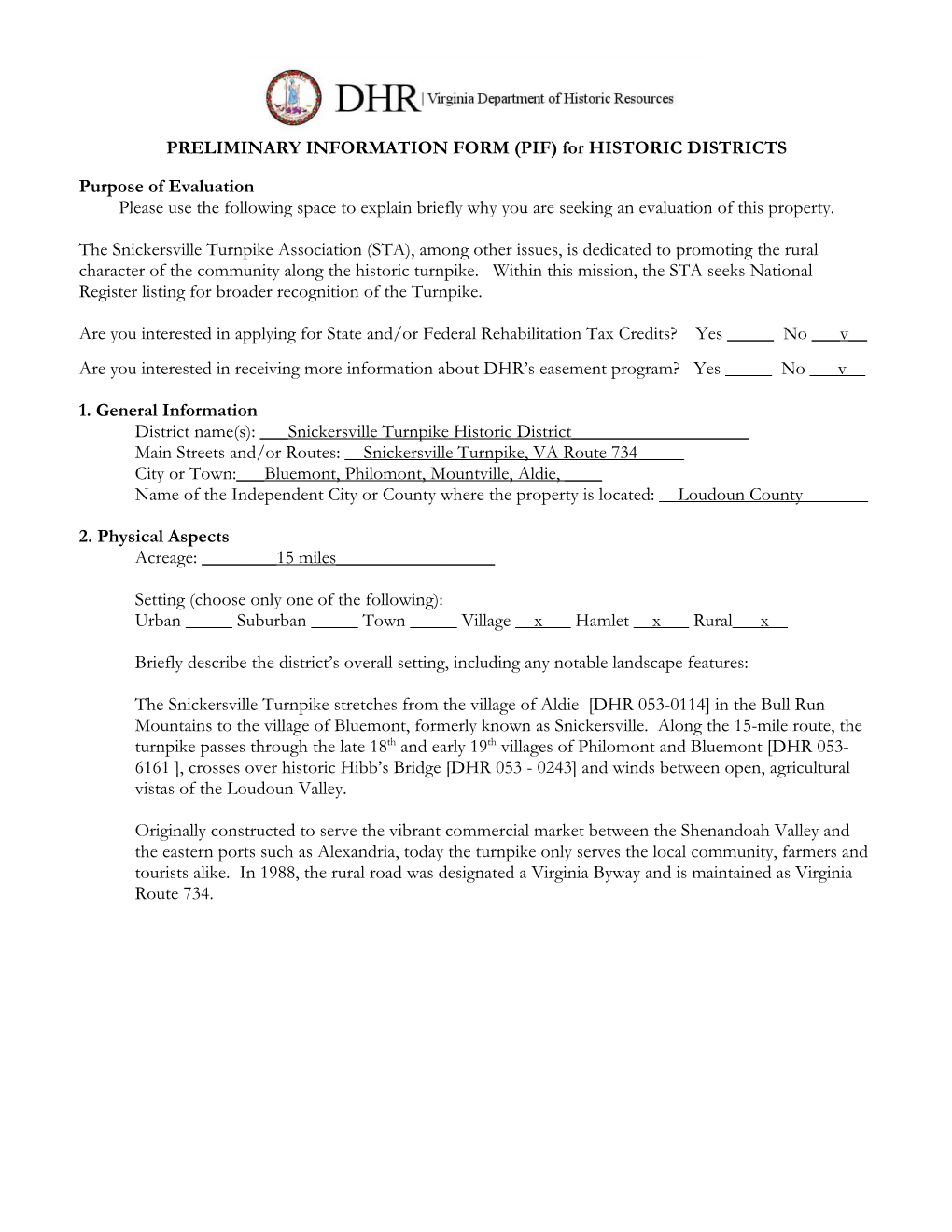

PIF) for HISTORIC DISTRICTS

@ DHRi Vrrgini, Dep,rtmort of Histo,i, Resom-ees PRELIMINARY INFORMATION FORM (PIF) for HISTORIC DISTRICTS Purpose of Evaluation Please use the following space to explain briefly why you are seeking an evaluation of this property. Although Loudoun' s rural road network pre-dates the 17 57 founding of the County, this historic asset has remained in continuous use in Loudoun's rural west. With Loudoun's continued shift away from its origins as a fanning community, there is the need to document the network and plan for its future survival with the hopes that the roads don't succumb to demands of modem, high-speed travel. Loudoun County's 2019 Comprehensive Plan acknowledges the importance of the county's historic roads as a contributing resource to the "character of the rural landscape." The Plan also recognizes the importance of continued use stating that in addition to vehicular travel, the rural road network "provides opportunities for recreational use such as hiking, biking and equestrian sports." 1 Local elected leaders have written in support of preservation of the roads. Letters are attached as an appendix to this PIF. America's Routes, a local group of engaged citizens, is dedicated to documenting Loudoun's Rural Road network as a means to educate the public as to the roads' historic significance. American's Routes believes that with education, there will be more public interest in preserving this unique historic asset. For more information, please see hllps://amcricasmutes.com Are you interested in applying for State and/or Federal Rehabilitation Tax Credits? Yes _No x Are you interested in receiving more information about DHR's easement program? Yes No_x_ 1.