POLITICAL POLICING in HONG KONG Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926 Hongkong Workers in an Anti-Imperialist Movement Robert JamesHorrocks Submitted in accordancewith the requirementsfor the degreeof PhD The University of Leeds Departmentof East Asian Studies October 1994 The candidateconfirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where referencehas been made to the work of others. 11 Abstract In this thesis, I study the Guangzhou-Hongkong strike of 1925-1926. My analysis differs from past studies' suggestions that the strike was a libertarian eruption of mass protest against British imperialism and the Hongkong Government, which, according to these studies, exploited and oppressed Chinese in Guangdong and Hongkong. I argue that a political party, the CCP, led, organised, and nurtured the strike. It centralised political power in its hands and tried to impose its revolutionary visions on those under its control. First, I describe how foreign trade enriched many people outside the state. I go on to describe how Chinese-run institutions governed Hongkong's increasingly settled non-elite Chinese population. I reject ideas that Hongkong's mixed-class unions exploited workers and suggest that revolutionaries failed to transform Hongkong society either before or during the strike. My thesis shows that the strike bureaucracy was an authoritarian power structure; the strike's unprecedented political demands reflected the CCP's revolutionary political platform, which was sometimes incompatible with the interests of Hongkong's unions. I suggestthat the revolutionary elite's goals were not identical to those of the unions it claimed to represent: Hongkong unions preserved their autonomy in the face of revolutionaries' attempts to control Hongkong workers. -

Head 122 — HONG KONG POLICE FORCE

Head 122 — HONG KONG POLICE FORCE Controlling officer: the Commissioner of Police will account for expenditure under this Head. Estimate 2002–03................................................................................................................................... 12,445.8m Establishment ceiling 2002–03 (notional annual mid-point salary value) representing an estimated 34 597 non-directorate posts at 31 March 2002 reducing by 337 posts to 34 260 posts at 31 March 2003......................................................................................................................................... 9,473.1m In addition there will be 77 directorate posts at 31 March 2002 and at 31 March 2003. Capital Account commitment balance................................................................................................. 305.3m Controlling Officer’s Report Programmes Programme (1) Maintenance of Law and These programmes contribute to Policy Area 9: Internal Security Order in the Community (Secretary for Security). Programme (2) Prevention and Detection of Crime Programme (3) Reduction of Traffic Accidents Programme (4) Operations Detail Programme (1): Maintenance of Law and Order in the Community 2000–01 2001–02 2001–02 2002–03 (Actual) (Approved) (Revised) (Estimate) Financial provision ($m) 6,223.6 5,995.3 5,986.4 6,081.8 (–3.7%) (–0.1%) (+1.6%) Aim 2 The aim is to maintain law and order through the deployment of efficient and well-equipped uniformed police personnel throughout the land regions. Brief Description 3 Law -

Thailand's Progress Report 2019 January – March

Royal Thai Government’s Progress Report on Anti-Human Trafficking Efforts (1 January – 31 March 2019) Table of Contents Prosecution 1 1 Statistics on Human Trafficking Litigation, Suspects, and Victims 1 2 Human Trafficking Cases in the Judicial Process 2 2.1 Human Trafficking Cases Handled by Inquiry Officers 2 2.2 Human Trafficking Cases Pursued by Public Prosecutors 3 2.3 Human Trafficking Cases Pursued by the Courts of Justice 3 3 Combatting Official Complicity in Human Trafficking Cases 4 4 Asset Restraint and Seizure 5 5 Witness Assistance and Protection 5 6 Thailand Anti-Trafficking in Persons Task Force (TATIP) and 5 Thailand Internet Crimes Against Children Task Force (TICAC) 7 Progress of the 2019 Plan 7 8 Capacity Building for Officers 8 9 Further Investigation on Prominent Cases of 2018 10 9.1 The Ugandan Transnational Sex Trafficking Case 10 9.2 The Facebook Case 10 9.3 The Victoria’s Secret Case 11 Protection 13 1 Respecting Victims’ Rights to Decide on Receiving Protection 13 2 Remedies through Compensations and Restitutions until 14 Reintegration into Society 3 Increased Capacity and Number of Interpreters 14 4 “Protect-U” Mobile Application For Victims to Improve Access 15 to Other Protection Services 5 Integrated Cooperation with Relevant Agencies to Better Provide 16 Effective Protection Prevention 18 1 Labour Management 18 2 Employer Change 19 3 Inspections of Migrant Labour Recruitment Agencies and Outbound 19 Employment Agencies 4 Labour Inspections 20 5 The Ratification of the C188 - Work in Fishing Convention, -

The Basic Law and Democratization in Hong Kong, 3 Loy

Loyola University Chicago International Law Review Volume 3 Article 5 Issue 2 Spring/Summer 2006 2006 The aB sic Law and Democratization in Hong Kong Michael C. Davis Chinese University of Hong Kong Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/lucilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael C. Davis The Basic Law and Democratization in Hong Kong, 3 Loy. U. Chi. Int'l L. Rev. 165 (2006). Available at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/lucilr/vol3/iss2/5 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola University Chicago International Law Review by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE BASIC LAW AND DEMOCRATIZATION IN HONG KONG Michael C. Davist I. Introduction Hong Kong's status as a Special Administrative Region of China has placed it on the foreign policy radar of most countries having relations with China and interests in Asia. This interest in Hong Kong has encouraged considerable inter- est in Hong Kong's founding documents and their interpretation. Hong Kong's constitution, the Hong Kong Basic Law ("Basic Law"), has sparked a number of debates over democratization and its pace. It is generally understood that greater democratization will mean greater autonomy and vice versa, less democracy means more control by Beijing. For this reason there is considerable interest in the politics of interpreting Hong Kong's Basic Law across the political spectrum in Hong Kong, in Beijing and in many foreign capitals. -

Regulating Undercover Agents' Operations and Criminal

This document is downloaded from CityU Institutional Repository, Run Run Shaw Library, City University of Hong Kong. Regulating undercover agents’ operations and criminal Title investigations in Hong Kong: What lessons can be learnt from the United Kingdom and South Australia Author(s) Chen, Yuen Tung Eutonia (陳宛彤) Chen, Y. T. E. (2012). Regulating undercover agents’ operations and criminal investigations in Hong Kong: What lessons can be learnt Citation from the United Kingdom and South Australia (Outstanding Academic Papers by Students (OAPS)). Retrieved from City University of Hong Kong, CityU Institutional Repository. Issue Date 2012 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2031/6855 This work is protected by copyright. Reproduction or distribution of Rights the work in any format is prohibited without written permission of the copyright owner. Access is unrestricted. Page | 1 LW 4635 INDEPENDENT RESEARCH Topic: Regulating Undercover Agents’ Operations and Criminal Investigations in Hong Kong: What Lessons can be learnt from the United Kingdom and South Australia? Student Name: CHEN Yuen Tung Eutonia1 Date: 13th April 2012 Word Count: 9570 (excluding cover page, footnote and bibliography) Number of Pages: 39 Abstract It is not a dispute that undercover police officers have a proper role to play in contemporary law enforcement. However, there is no clear legislation in Hong Kong on the issue of whether the undercover agent is, at law, an offender of crime(s). This paper would examine the limitations of the prevailing undercover policing laws in Hong Kong and suggest possible recommendations. In particular, a comparative study of the United Kingdom and South Australia would be made to investigate whether Hong Kong should enact a legislation regulating undercover operations and criminal investigations. -

Country Reports on Human Rights Practices 2003: China (Includes Tibet, Hong Kong and Macau)

Page 1 of 66 China (includes Tibet, Hong Kong, and Macau) Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2003 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor February 25, 2004 (Note: Also see the section for Tibet, the report for Hong Kong, and the report for Macau.) The People's Republic of China (PRC) is an authoritarian state in which, as directed by the Constitution, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP or Party) is the paramount source of power. Party members hold almost all top government, police, and military positions. Ultimate authority rests with the 24-member political bureau (Politburo) of the CCP and its 9-member standing committee. Leaders made a top priority of maintaining stability and social order and were committed to perpetuating the rule of the CCP and its hierarchy. Citizens lacked both the freedom peacefully to express opposition to the Party-led political system and the right to change their national leaders or form of government. Socialism continued to provide the theoretical underpinning of national politics, but Marxist economic planning has given way to pragmatism, and economic decentralization increased the authority of local officials. The Party's authority rested primarily on the Government's ability to maintain social stability; appeals to nationalism and patriotism; Party control of personnel, media, and the security apparatus; and continued improvement in the living standards of most of the country's 1.3 billion citizens. The Constitution provides for an independent judiciary; however, in practice, the Government and the CCP, at both the central and local levels, frequently interfered in the judicial process and directed verdicts in many high-profile cases. -

Considering the Creation of a Domestic Intelligence Agency in the United States

HOMELAND SECURITY PROGRAM and the INTELLIGENCE POLICY CENTER THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND Homeland Security Program RAND Intelligence Policy Center View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. -

List of Access Officer (For Publication)

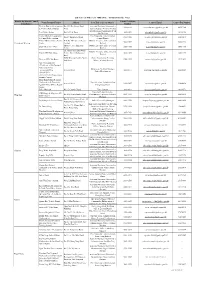

List of Access Officer (for Publication) - (Hong Kong Police Force) District (by District Council Contact Telephone Venue/Premise/FacilityAddress Post Title of Access Officer Contact Email Conact Fax Number Boundaries) Number Western District Headquarters No.280, Des Voeux Road Assistant Divisional Commander, 3660 6616 [email protected] 2858 9102 & Western Police Station West Administration, Western Division Sub-Divisional Commander, Peak Peak Police Station No.92, Peak Road 3660 9501 [email protected] 2849 4156 Sub-Division Central District Headquarters Chief Inspector, Administration, No.2, Chung Kong Road 3660 1106 [email protected] 2200 4511 & Central Police Station Central District Central District Police Service G/F, No.149, Queen's Road District Executive Officer, Central 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 Central and Western Centre Central District Shop 347, 3/F, Shun Tak District Executive Officer, Central Shun Tak Centre NPO 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 Centre District 2/F, Chinachem Hollywood District Executive Officer, Central Central JPC Club House Centre, No.13, Hollywood 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 District Road POD, Western Garden, No.83, Police Community Relations Western JPC Club House 2546 9192 [email protected] 2915 2493 2nd Street Officer, Western District Police Headquarters - Certificate of No Criminal Conviction Office Building & Facilities Manager, - Licensing office Arsenal Street 2860 2171 [email protected] 2200 4329 Police Headquarters - Shroff Office - Central Traffic Prosecutions Enquiry Counter Hong Kong Island Regional Headquarters & Complaint Superintendent, Administration, Arsenal Street 2860 1007 [email protected] 2200 4430 Against Police Office (Report Hong Kong Island Room) Police Museum No.27, Coombe Road Force Curator 2849 8012 [email protected] 2849 4573 Inspector/Senior Inspector, EOD Range & Magazine MT. -

Ethical Hacking

Ethical Hacking Alana Maurushat University of Ottawa Press ETHICAL HACKING ETHICAL HACKING Alana Maurushat University of Ottawa Press 2019 The University of Ottawa Press (UOP) is proud to be the oldest of the francophone university presses in Canada and the only bilingual university publisher in North America. Since 1936, UOP has been “enriching intellectual and cultural discourse” by producing peer-reviewed and award-winning books in the humanities and social sciences, in French or in English. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Title: Ethical hacking / Alana Maurushat. Names: Maurushat, Alana, author. Description: Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20190087447 | Canadiana (ebook) 2019008748X | ISBN 9780776627915 (softcover) | ISBN 9780776627922 (PDF) | ISBN 9780776627939 (EPUB) | ISBN 9780776627946 (Kindle) Subjects: LCSH: Hacking—Moral and ethical aspects—Case studies. | LCGFT: Case studies. Classification: LCC HV6773 .M38 2019 | DDC 364.16/8—dc23 Legal Deposit: First Quarter 2019 Library and Archives Canada © Alana Maurushat, 2019, under Creative Commons License Attribution— NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Printed and bound in Canada by Gauvin Press Copy editing Robbie McCaw Proofreading Robert Ferguson Typesetting CS Cover design Édiscript enr. and Elizabeth Schwaiger Cover image Fragmented Memory by Phillip David Stearns, n.d., Personal Data, Software, Jacquard Woven Cotton. Image © Phillip David Stearns, reproduced with kind permission from the artist. The University of Ottawa Press gratefully acknowledges the support extended to its publishing list by Canadian Heritage through the Canada Book Fund, by the Canada Council for the Arts, by the Ontario Arts Council, by the Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences through the Awards to Scholarly Publications Program, and by the University of Ottawa. -

2020 Cross-Border Corporate Criminal Liability Survey 2020 Cross-Border Corporate Criminal Liability Survey

2019 ANNUAL M&A REVIEW 2020 CROSS-BORDER CORPORATE CRIMINAL LIABILITY SURVEY 2020 CROSS-BORDER CORPORATE CRIMINAL LIABILITY SURVEY TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . 1 MIDDLE EAST . 106 GLOSSARY . 4 ISRAEL . 107 AFRICA . 5 SAUDI ARABIA. 113 SOUTH AFRICA. .. 6 UNITED ARAB EMIRATES . 117 ASIA PACIFIC . 10 NORTH AMERICA . 121 AUSTRALIA . .11 CANADA . 122 CHINA . 16 MEXICO . 126 HONG KONG . 20 UNITED STATES . 131 INDIA . 25 SOUTH AMERICA . .. 135 INDONESIA . 30 ARGENTINA . 136 JAPAN . 34 BRAZIL . 141 SINGAPORE . 38 CHILE . 145 TAIWAN (REPUBLIC OF CHINA) . 43 VENEZUELA . 149 CENTRAL AMERICA . 47 CONTACTS . 152 COSTA RICA . 48 EUROPE . 52 BELGIUM . 53 FRANCE . 57 GERMANY . 62 ITALY . 69 NETHERLANDS. .. 76 RUSSIA . 84 SPAIN . 87 SWITZERLAND . 92 TURKEY . 96 UKRAINE . 99 UNITED KINGDOM . 103 Jones Day White Paper 2020 CROSS-BORDER CORPORATE CRIMINAL LIABILITY SURVEY INTRODUCTION For any company, the risk that employees or agents may countries, and the ability of industry participants to engage in criminal conduct in connection with their work assert (accurately or inaccurately) that a competitor has and thereby potentially expose the company (or at least broken the law . Multinational companies are at ever- the responsible individuals) to criminal, administrative, increasing risk of aggressive criminal enforcement, and/or civil liability is ever present; for multinational often across numerous jurisdictions at once . companies, which are necessarily subject to the laws To be sure, aggressive enforcement of corporate of multiple jurisdictions, this risk is only heightened . crime can help ensure that such crime is appropriately How a company manages the risk of corporate criminal punished and deterred and that the rights and interests liability, in particular, can not only determine its success, of victims are honored through a criminal proceeding . -

Volume 4, Number 2 2016

Volume 4, Number 2 2016 Salus Journal A peer-reviewed, open access journal for topics concerning law enforcement, national security, and emergency management Published by Charles Sturt University Australia ISSN 2202-5677 Editorial Board—Associate Editors Volume 4, Number 2, 2016 Dr Jeremy G Carter www.salusjournal.com Indiana University-Purdue University Dr Anna Corbo Crehan Charles Sturt University, Canberra Published by Dr Ruth Delaforce Griffith University, Queensland Charles Sturt University Australian Graduate School of Policing and Dr Garth den Heyer Security New Zealand Police PO Box 168 Dr Victoria Herrington Manly, New South Wales, Australia, 1655 Australian Institute of Police Management Dr Valerie Ingham ISSN 2202-5677 Charles Sturt University, Canberra Dr Stephen Marrin James Madison University, Virginia Dr Alida Merlo Advisory Board Indiana University of Pennsylvania Associate Professor Nicholas O’Brien (Chair) Dr Alexey D. Muraviev Professor Simon Bronitt Curtin University, Perth, Western Australia Professor Ross Chambers Dr Maid Pajevic Professor Mick Keelty APM, AO College 'Logos Center' Mostar, Mr Warwick Jones, BA MDefStudies Bosnia-Herzegovina Dr Felix Patrikeeff University of Adelaide, South Australia Dr Tim Prenzler Editor-in-Chief Griffith University, Queensland Dr Henry Prunckun Dr Suzanna Ramirez Charles Sturt University, Sydney University of Queensland Dr Susan Robinson Assistant Editor Charles Sturt University, Canberra Ms Kellie Smyth, BA, MApAnth, GradCert Dr Rick Sarre (LearnTeach in HigherEd) University of -

Seventh United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems, Table Comments by Country

UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNIES Office on Drugs and Crime Division for Policy Analysis and Public Affairs Seventh United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems, covering the period 1998 - 2000 Comments by Table 1. Police personnel, by sex, and financial resources Alternative reference date to 31 December POLICE 1. Police personnel, by sex, and financial resources Alternative reference date to 31 December England & Wales 30 September Japan 1 April 2. Crimes recorded in criminal (police) statistics, by type of crime including attempts to commit crimes What is (are) the source(s) of the data provided in this table? Australia Recorded Crime Statistics 2000 (cat: 4510.0) Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Azerbaijan Reports on crimes Barbados Royal Barbados Police Force, Research and Development Department Bulgaria Ministry of Interior - Regular Report Canada Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, Uniform Crime Report and Homicide Survey, Statistics Canada. Chile S.I.E.C (Sistema Integrado Estadistico de Carabineros) Colombia Policia Nacional, Direccion Central de Policia Judicial, Centro de Investigaciones Criminologicas Côte d'Ivoire Direction Centrale de la police Judiciaire Czech Republic Recording and Statistical System of Crime maintained by the Police of the Czech Republic Denmark Statistics of reported crimes, National Commissioner of Police, Department E. Dominica Criminal Records Office Friday, March 19, 2004 Page 1 of 22 2. Crimes recorded in criminal (police) statistics, by type of crime includi What is (are) the source(s) of the data provided in this table? England & Wales Recorded crime database Finland Statistics Finland: Yearbook of Justice Statistics (SVT) Georgia Ministry of Internal Affairs of Georgia.