A Tale of Two Somali Community-Based Organizations in Cairo: Between Assistance, Agency &Community Formations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tol, Xeer, and Somalinimo: Recognizing Somali And

Tol , Xeer , and Somalinimo : Recognizing Somali and Mushunguli Refugees as Agents in the Integration Process A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Vinodh Kutty IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY David M. Lipset July 2010 © Vinodh Kutty 2010 Acknowledgements A doctoral dissertation is never completed without the help of many individuals. And to all of them, I owe a deep debt of gratitude. Funding for this project was provided by two block grants from the Department of Anthropology at the University of Minnesota and by two Children and Families Fellowship grants from the Annie E. Casey Foundation. These grants allowed me to travel to the United Kingdom and Kenya to conduct research and observe the trajectory of the refugee resettlement process from refugee camp to processing for immigration and then to resettlement to host country. The members of my dissertation committee, David Lipset, my advisor, Timothy Dunnigan, Frank Miller, and Bruce Downing all provided invaluable support and assistance. Indeed, I sometimes felt that my advisor, David Lipset, would not have been able to write this dissertation without my assistance! Timothy Dunnigan challenged me to honor the Somali community I worked with and for that I am grateful because that made the dissertation so much better. Frank Miller asked very thoughtful questions and always encouraged me and Bruce Downing provided me with detailed feedback to ensure that my writing was clear, succinct and organized. I also have others to thank. To my colleagues at the Office of Multicultural Services at Hennepin County, I want to say “Thank You Very Much!” They all provided me with the inspiration to look at the refugee resettlement process more critically and dared me to suggest ways to improve it. -

Making Moral Worlds: Individual and Social Processes of Meaning-Making in a Somali Diaspora Anna Jacobsen Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) 1-1-2011 Making Moral Worlds: Individual and Social Processes of Meaning-Making in a Somali Diaspora Anna Jacobsen Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Recommended Citation Jacobsen, Anna, "Making Moral Worlds: Individual and Social Processes of Meaning-Making in a Somali Diaspora" (2011). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 592. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/592 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Anthropology Dissertation Examination Committee: John R. Bowen, chair Geoff Childs Carolyn Lesorogol Rebecca Lester Shanti Parikh Timothy Parsons Carolyn Sargent Making Moral Worlds: Individual and Social Processes of Meaning Making in a Somali Diaspora by Anna Lisa Jacobsen A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2011 Saint Louis, Missouri Abstract: I argue that most Somalis living in exile in the Eastleigh neighborhood of Nairobi, Kenya are deeply concerned with morality both as individually performed and proven, and as socially defined, authorized and constructed. In this dissertation, I explore various aspects of Somali morality as it is constructed, debated, and reinforced by individual women living in Eastleigh. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Egyptian

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Egyptian Urban Exigencies: Space, Governance and Structures of Meaning in a Globalising Cairo A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Global Studies by Roberta Duffield Committee in charge: Professor Paul Amar, Chair Professor Jan Nederveen Pieterse Assistant Professor Javiera Barandiarán Associate Professor Juan Campo June 2019 The thesis of Roberta Duffield is approved. ____________________________________________ Paul Amar, Committee Chair ____________________________________________ Jan Nederveen Pieterse ____________________________________________ Javiera Barandiarán ____________________________________________ Juan Campo June 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis committee at the University of California, Santa Barbara whose valuable direction, comments and advice informed this work: Professor Paul Amar, Professor Jan Nederveen Pieterse, Professor Javiera Barandiarán and Professor Juan Campo, alongside the rest of the faculty and staff of UCSB’s Global Studies Department. Without their tireless work to promote the field of Global Studies and committed support for their students I would not have been able to complete this degree. I am also eternally grateful for the intellectual camaraderie and unending solidarity of my UCSB colleagues who helped me navigate Californian graduate school and come out the other side: Brett Aho, Amy Fallas, Tina Guirguis, Taylor Horton, Miguel Fuentes Carreño, Lena Köpell, Ashkon Molaei, Asutay Ozmen, Jonas Richter, Eugene Riordan, Luka Šterić, Heather Snay and Leila Zonouzi. I would especially also like to thank my friends in Cairo whose infinite humour, loyalty and love created the best dysfunctional family away from home I could ever ask for and encouraged me to enroll in graduate studies and complete this thesis: Miriam Afifiy, Eman El-Sherbiny, Felix Fallon, Peter Holslin, Emily Hudson, Raïs Jamodien and Thomas Pinney. -

My Dostoyevsky Syndrome: How I Escaped Being a Self-Hating Somali

My Dostoyevsky Syndrome: How I Escaped Being a Self-Hating Somali Said S. Samatar The habit of reflection is the most pernicious habit of civilized man. Joseph Conrad in Lord Jim Allahayow nin ii daran maxaan daafta hore seexshay Nin ii daaqsanaayana maxaan daafida u kariyey Jidhku nin uuna dooneyn maxaan hadalka deeqsiiyey Ma degdegee xaajada maxaan ugu dulqaad yeeshay Weji debecsan, dayma aan dareen gelin dubaaqiisa Qosol dibadda yaalloon ka iman dhuunta dacalkeeda Isagoon digniin qabin maxaan kaga deyaan siiyey If any man intended aught of villainy against me By God, how snug I made the forecourt for his bed-mat, nonetheless! And if, with aggression in his thoughts He pastured his horses to get them battle-fit How in spite of this I made him griddle-cakes of maize to eat! Amiably I conversed with him for whom my body felt revulsion. I did not hurry, I was patient in dealing with his tricks. I showed a relaxed and easy mien, My looks gave no grounds for suspicion in his mind Laughter on the surface, not rising from the gullet’s depth. Then, when he was all unknowing and unwarned, O how I struck him down! Ugaas Nuur I. Introduction This is an essay in self-doubt, and in subsequent strivings of the soul to shake off the legion of private demons clamoring to offer their unbid- den company in midnight visitations of the blues. As such, it could be catalogued as a confessional item, as revealing of personality quirks as of political mishaps. A striving confessor, much like a drowning man, must grasp at straws, if only to stave off the looming specter of lost honor. -

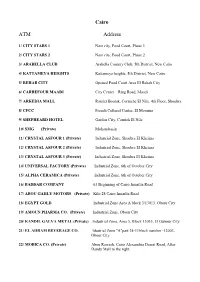

Cairo ATM Address

Cairo ATM Address 1/ CITY STARS 1 Nasr city, Food Court, Phase 1 2/ CITY STARS 2 Nasr city, Food Court, Phase 2 3/ ARABELLA CLUB Arabella Country Club, 5th District, New Cairo 4/ KATTAMEYA HEIGHTS Kattameya heights, 5th District, New Cairo 5/ REHAB CITY Opened Food Court Area El Rehab City 6/ CARREFOUR MAADI City Center – Ring Road, Maadi 7/ ARKEDIA MALL Ramlet Boulak, Corniche El Nile, 4th Floor, Shoubra 8/ CFCC French Cultural Center, El Mounira 9/ SHEPHEARD HOTEL Garden City, Cornish El Nile 10/ SMG (Private) Mohandessin 11/ CRYSTAL ASFOUR 1 (Private) Industrial Zone, Shoubra El Kheima 12/ CRYSTAL ASFOUR 2 (Private) Industrial Zone, Shoubra El Kheima 13/ CRYSTAL ASFOUR 3 (Private) Industrial Zone, Shoubra El Kheima 14/ UNIVERSAL FACTORY (Private) Industrial Zone, 6th of October City 15/ ALPHA CERAMICA (Private) Industrial Zone, 6th of October City 16/ BADDAR COMPANY 63 Beginning of Cairo Ismailia Road 17/ ABOU GAHLY MOTORS (Private) Kilo 28 Cairo Ismailia Road 18/ EGYPT GOLD Industrial Zone Area A block 3/13013, Obour City 19/ AMOUN PHARMA CO. (Private) Industrial Zone, Obour City 20/ KANDIL GALVA METAL (Private) Industrial Zone, Area 5, Block 13035, El Oubour City 21/ EL AHRAM BEVERAGE CO. Idustrial Zone "A"part 24-11block number -12003, Obour City 22/ MOBICA CO. (Private) Abou Rawash, Cairo Alexandria Desert Road, After Dandy Mall to the right. 23/ COCA COLA (Pivate) Abou El Ghyet, Al kanatr Al Khayreya Road, Kaliuob Alexandria ATM Address 1/ PHARCO PHARM 1 Alexandria Cairo Desert Road, Pharco Pharmaceutical Company 2/ CARREFOUR ALEXANDRIA City Center- Alexandria 3/ SAN STEFANO MALL El Amria, Alexandria 4/ ALEXANDRIA PORT Alexandria 5/ DEKHILA PORT El Dekhila, Alexandria 6/ ABOU QUIER FERTLIZER Eltabia, Rasheed Line, Alexandria 7/ PIRELLI CO. -

Trip to Egypt January 25 to February 8, 2020. Day 1

Address : Group72,building11,ap32, El Rehab city. Cairo ,Egypt. tel : 002 02 26929768 cell phone: 002 012 23 16 84 49 012 20 05 34 44 Website : www.mirusvoyages.com EMAIL:[email protected] Trip to Egypt January 25 to February 8, 2020. Day 1 Travel from Chicago to Cairo Day 2 Arrival at Cairo airport, meet & assistance, transfer to the hotel. Overnight at the hotel in Cairo. Day 3 Saqqara, the oldest complete stone building complex known in history, Saqqara features numerous pyramids, including the world-famous Step pyramid of Djoser, Visit the wonderful funerary complex of the King Zoser & Mastaba (Arabic word meaning 'bench') of a Noble. Lunch in a local restaurant. Visit the three Pyramids of Giza, the pyramid of Cheops is the oldest of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, and the only one to remain largely intact. ), the Great Pyramid was the tallest man-made structure in the world for more than 3,800 years. The temple of the valley & the Sphinx. Overnight at the hotel in Cairo. Day 4 Visit the Mokattam church, also known by Cave Church & garbage collectors( Zabbaleen) Mokattam, it is the largest church in the Middle East, seating capacity of 20,000. Visit the Coptic Cairo, Visit The Church of St. Sergius (Abu Sarga) is the oldest church in Egypt dating back to the 5th century A.D. The church owes its fame to having been constructed upon the crypt of the Holy Family where they stayed for three months, visit the Hanging Church (The Address : Group72,building11,ap32, El Rehab city. -

1 the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR THOMAS N. HULL III Interviewed by: Daniel F. Whitman Initial Interview Date: January 8, 2010 Copyri ht 2012 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in New York, raised in Massachusetts Educated at Dickinson College and Columbia University Sierra Leone: Peace Corps Volunteer; Primary school teacher 19681c1.22 ,illage environment Living conditions Ambassador Robert Miner Fellow Peace Corps volunteers Fianc5e Columbia (niversity: Student, Education and International Affairs 1.2211.23 Degrees: International Education and International Affairs African studies ew York City, NY- Institute of International Education 8IIE9 1.2311.26 Fulbright Program Senator Fulbright :oined the Foreign Service: (SIA 1.26 Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo: Public Affairs Trainee 1.2611.22 Mobutu and Mama Mobutu Program officers (SIA staff and operations (SAID Security Belgians Environment Closeing Consulate Kisangani 8former Stanleyville9 Brazzaville, Republic of the Congo- TDY Public Affairs Officer 1.22 Communist government 1 Concerts Kinshasa, 8Continued9 1.2211.20 Environment Mobuto’s Zairian art collection Feccan Fair Personnel issues Pretoria, South Africa: Assistant Cultural Affairs Officer 1.2011.00 Effects of Soweto riots Apartheid Afrikaners on1Afrikaner whites Cleveland International Program Crossroads Africa (S policy International ,isitors Program Ambassador Edmonson Ambassador Bowdler Personnel Black entrepreneurs Official entertainment Foreign -

A Comparative Class Study in Two Contemporary Cairo Neighborhoods

American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Theses and Dissertations 2-1-2018 Marital economies: A comparative class study in two contemporary Cairo neighborhoods Sahar Mohsen Mohammad Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds Recommended Citation APA Citation Mohammad, S. (2018).Marital economies: A comparative class study in two contemporary Cairo neighborhoods [Master’s thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/694 MLA Citation Mohammad, Sahar Mohsen. Marital economies: A comparative class study in two contemporary Cairo neighborhoods. 2018. American University in Cairo, Master's thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/694 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Marital Economies: A Comparative Class Study in Two Contemporary Cairo Neighborhoods Dedication To the souls of my father and mother who grew up the insisting on success in me. To my beloved family: My husband: Ahmad Sabry My daughters: Noura and Yosra My sons: Sherif and Mahmoud ii Table of Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................................................... v Neoliberalism, Consumerism and the Production of New Subjectivity ...................................................... -

(I) the SOCIAL STRUCTUBE of Soumn SOMALI TRIB by Virginia I?

(i) THE SOCIAL STRUCTUBE OF SOumN SOMALI TRIB by Virginia I?lling A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of London. October 197]. (ii) SDMMARY The subject is the social structure of a southern Somali community of about six thousand people, the Geledi, in the pre-colonial period; and. the manner in which it has reacted to colonial and other modern influences. Part A deals with the pre-colonial situation. Section 1 deals with the historical background up to the nineteenth century, first giving the general geographic and ethnographic setting, to show what elements went to the making of this community, and then giving the Geledj's own account of their history and movement up to that time. Section 2 deals with the structure of the society during the nineteenth century. Successive chapters deal with the basic units and categories into which this community divided both itself and the others with which it was in contact; with their material culture; with economic life; with slavery, which is shown to have been at the foundation of the social order; with the political and legal structure; and with the conduct of war. The chapter on the examines the politico-religious office of the Sheikh or Sultan as the focal point of the community, and how under successive occupants of this position, the Geledi became the dominant power in this part of Somalia. Part B deals with colonial and post-colonial influences. After an outline of the history of Somalia since 1889, with special reference to Geledi, the changes in society brought about by those events are (iii) described. -

Nume Copii | Lancelot | Kenya

Prenume Insemnatate 2 ABBA Ghanaian name for females born on Thursday. 3 ABEBA Ethiopian female name meaning ";flower."; Yoruba of Nigeria female name meaning ";we asked and got her"; or 4 ABEBI ";we asked for her and she came to us."; 5 ABENA Akan of Ghana name for females born on Tuesday. Tigrinya of Ethiopia female name meaning ";she has made it light, she 6 ABRIHET emanates light."; 7ACACIA ";thorny."; 8 ACHAN Dinka of south Sudan name for a female child in the first pair of twins. 9 ADA Ibo of Nigeria name for firstborn females. 10 ADAMA Ibo of Nigeria female name meaning ";beautiful child"; or ";queenly."; Amharic and Tigrinya of Ethiopia female name meaning ";she has 11 ADANECH rescued them."; 12 ADANNA Ibo of Nigeria female name meaning ";father's daughter."; 13 ADEOLA Yoruba of Nigeria female name meaning ";crown of honor."; 14 ADETOUN Yoruba of Nigeria female name meaning ";princess."; 15 ADHIAMBO Luo of Kenya name for females born after sunset. Amharic of Ethiopia word sometimes used as a female name, 16 ADINA meaning ";she has saved."; 17 ADJOA Akan of Ghana names for females born on Monday; peace. 18ADOWA noble. Ewe of Ghana female name for the firstborn child of a second 19 AFAFA husband. 20 AFIA Akan of Ghana name for females born on Friday. Name meaning ";peaceful ruler"; used by ancient Romans and Greeks 21 AFRA for females of African origin. 22 AFUA born on Friday. Swahili female name (also spelled AFIYA) and Kiswahili word meaning 23 AFYA ";health.";Afya Bora means ";good health."; Ewe of Ghana name meaning ";life is precious.";(Could be shortened 24 AGBENYAGA to NYAGA.) Yoruba of Nigeria female name meaning ";difficult birth,"; such as a 25 AINA child born with umbilical cord around neck. -

Transcript of Oral History Interview with Abdi Warsame

Abdi Warsame Narrator Ahmed Ismail Yusuf Interviewer June 12, 2014 Minneapolis, Minnesota Abdi Warsame -AW Ahmed Ismail Yusuf -AY AY: This is Ahmed Ismail Yusuf recording for the Minnesota Historical Society Somali Oral History Project. I am here with Abdi Warsame, who is the highest Somali official elected in Minneapolis—Minnesota, actually, in that matter. Abdi, welcome to the interview, and thanks for agreeing to it. AW: Oh, thank you, Yusuf. I appreciate the opportunity. AY: So I normally actually start it from the basis of where one was born and when, sort of those things. But in your case, let us just exactly talk about when you came to Minneapolis first of all. AW: Well, I came to Minneapolis in the year 2006, which is about eight years ago now. AY: And the reason why I am just exactly asking that question is just that it seems that, to me actually, with the speed of light you traveled through the ranks and became the first Somali official elected in this state. Nationwide, you are the second Somali elected. So did you have that ambition when you actually came here, or how did it start? AW: Well, to go back a little bit, I didn’t come directly from Somalia. I came from London, England. I was born in Somalia, and I was raised in the UK, across the pond. I grew up in a place called Leytonstone in East London. I was educated in the UK. I went to King’s College, University of London. I graduated from Middlesex University, and I also got a master’s degree from Greenwich University with an international business degree. -

Arab African International Bank (AAIB) Maintained Its Leading Our Ability to Confront Future Challenges and Growth Position As a Leading Financial Institution

“50 GOLDEN YEARS OF VALUE CREATION” VISI N To be the leading financial group in Egypt providing innovative services with a strong regional presence being the gateway for international business into the region. Cover: The Royal Geographical | Society Qasr El Aini Street | Photographer: Barry Iverson This image: The Royal Geographical Society | Qasr El Aini Street | Photographer: Shahir Sirry “ 50 GOLDEN YEARS OF CONFIDENCE” been at the core of AAIB’s values, guiding all its interactions with its clients and a mission to do what is right. TABLE F C NTENT Shareholders 4 Board of Directors 5 Chairman’s Statement 6 Vice Chairman & Managing Director’s Report 8 Financial Statements 13 Balance sheet 14 Income statement 14 Statement of changes in owners’ equity 15 Statement of cash flows 15 Statement of proposed appropriation 16 Notes to the financial statements 16 Auditors’ Report 50 Branches 52 Location description Door of “Inal Al Yusufi” Mosque | Khayameya | Islamic Cairo | Photographer: Karim El Hayawan “ GOLDEN YEARS OF 50 STRENGTH” Only when a solid foundation is built, can an entity really prosper. The trust we have in the Central Bank of Egypt, the Kuwait Investment Authority as shareholders and the stability having a strong dollar based equity gives us the SHARH LDERS PERCENTAGE OF HOLDING Central Bank of Egypt, Egypt 49.37% Kuwait Investment Authority, Kuwait 49.37% Others 1.26% Others 1.26% Kuwait Investment Authority, Central Bank Kuwait of Egypt, 49.37% Egypt 49.37% The Royal Geographical | Society Qasr El Aini Street | Photographer: Barry Iverson “ GOLDEN YEARS OF 50 PASSION ” Our passion is what fuels our growth.