When the City Became a Stage Exposing Drama on Every Corner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aroundmanhattan

Trump SoHo Hotel South Cove Statue of Liberty 3rd Avenue Peter J. Sharp Boat House Riverbank State Park Chelsea Piers One Madison Park Four Freedoms Park Eastwood Time Warner Center Butler Rogers Baskett Handel Architects and Mary Miss, Stanton Eckstut, F A Bartholdi, Richard M Hunt, 8 Spruce Street Rotation Bridge Robert A.M. Stern & Dattner Architects and 1 14 27 40 53 66 Cetra Ruddy 79 Louis Kahn 92 Sert, Jackson, & Assocs. 105 118 131 144 Skidmore, Owings & Merrill Marner Architecture Rockwell Group Susan Child Gustave Eiffel Frank Gehry Thomas C. Clark Armand LeGardeur Abel Bainnson Butz 23 East 22nd Street Roosevelt Island 510 Main St. Columbus Circle Warren & Wetmore 246 Spring Street Battery Park City Liberty Island 135th St Bronx to E 129th 555 W 218th Street Hudson River -137th to 145 Sts 100 Eleventh Avenue Zucotti Park/ Battery Park & East River Waterfront Queens West / NY Presbyterian Hospital Gould Memorial Library & IRT Powerhouse (Con Ed) Travelers Group Waterside 2009 Addition: Pei Cobb Freed Park Avenue Bridge West Harlem Piers Park Jean Nouvel with Occupy Wall St Castle Clinton SHoP Architects, Ken Smith Hunters Point South Hall of Fame McKim Mead & White 2 15 Kohn Pedersen Fox 28 41 54 67 Davis, Brody & Assocs. 80 93 and Ballinger 106 Albert Pancoast Boiler 119 132 Barbara Wilks, Archipelago 145 Beyer Blinder Belle Cooper, Robertson & Partners Battery Park Battery Maritime Building to Pelli, Arquitectonica, SHoP, McKim, Mead, & White W 58th - 59th St 388 Greenwich Street FDR Drive between East 25th & 525 E. 68th Street connects Bronx to Park Ave W127th St & the Hudson River 100 11th Avenue Rutgers Slip 30th Streets Gantry Plaza Park Bronx Community College on Eleventh Avenue IAC Headquarters Holland Tunnel World Trade Center Site Whitehall Building Hospital for Riverbend Houses Brooklyn Bridge Park Citicorp Building Queens River House Kingsbridge Veterans Grant’s Tomb Hearst Tower Frank Gehry, Adamson Ventilation Towers Daniel Libeskind, Norman Foster, Henry Hardenbergh and Special Surgery Davis, Brody & Assocs. -

100 Eleventh Avenue New York, New York

100 Eleventh Avenue New York, New York Tyler Graybill | Structural Option Consultant: Professor Thomas Boothby Wednesday, October 28th 2009 ©archpartners.com Technical Report II Tyler E. Graybill |100 Eleventh Avenue | New York, New York Structural Option | Professor T. Boothby 10/28/09 Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 4 Existing Structural System Summary Foundations ............................................................................................................................ 5 Gravity System ........................................................................................................................ 6 Lateral System ....................................................................................................................... 10 Code Design & Standards ........................................................................................................ 11 Material Summary .................................................................................................................... 11 Building Loads Gravity .................................................................................................................................. 12 Floor Systems .......................................................................................................................... -

Chapter 2: Land Use, Zoning and Public Policy

Special West Chelsea District Rezoning and High Line Open Space EIS CHAPTER 2: LAND USE, ZONING, AND PUBLIC POLICY A. INTRODUCTION The proposed action would not result in significant adverse land use impacts and would be consistent with zoning and public policies in West Chelsea and adjacent areas. A detailed assessment of land use, zoning, and public policy is appropriate if an action would result in a significant change in land use or would substantially affect regulations or policies governing land use. The proposed action would result in substantial land use changes on Tenth and Eleventh Avenues, between W. 16th and W. 22nd Streets and W. 24th and W. 30th Streets. West Chelsea is currently occupied by art galleries, parking lots, auto-repair facilities, manufacturing and storage uses, and bars and nightclubs. By 2013, with the proposed action, West Chelsea would be transformed into a mixed-use community, with much of the area occupied by primarily residential buildings with commercial, including retail and gallery uses, community facilities such as museums and a new linear open space on the High Line. While the anticipated changes are significant, they are not expected to result in significant adverse land use impacts. In recent years, the adjacent Chelsea neighborhood east of Tenth Avenue has experienced an increase in residential development, in the form of new construction and conversions and enlargements of existing buildings. Similarly, the northwest corner of the West Village, directly south of West Chelsea has experienced a rise in residential and commercial redevelopment, as former industrial buildings have converted to residential and commercial uses. -

Architecture

architecture ELEVATED THE TWIN 3 5 PLEASURES OF THE The High Line Building 459 West 18th Street 450 West 14th Street; Morris Adjmi Della Valle Bernheimer HIGH LINE: A PETITE A muscular former meatpacking A smaller and more successful plant that was always impaled companion piece to 245 Tenth NEW PARK, AND by the elevated tracks will, when it’s (seen on the following pages). finished, now also carry an office 4 The interlocking black and tower on its shoulders and white volumes suggest an A DISTRICT OF LIVELY shelter shopping in its base. Old The Caledonia M. C. Escher print, but there’s industrial buildings are generous and 450 West 17th Street; nothing impossible about the way ARCHITECTURE. strong, and it makes sense Handel Architects sunlight streams in one of the to reuse them rather than The High Line pioneer is penthouse’s mammoth windows by justin davidson tear them down. a big but surprisingly and out the other side. 1 retiring building, deftly Standard Hotel disguising its bulk and 7 848 Washington Street; leaving the limelight to its The IAC Building Polshek Partnership neighbors. 555 West 18th Street; The concrete-legged Gehry Partners brute offers its guests Frank Gehry’s glass prime views of the High schooner, one of the Line; its glassed-in few new workplaces in rooms will present park the area, set the visitors with equally 6 neighborhood standard stimulating spectacles. for fanciful design. 2 Chelsea Modern 447 West 18th Street; Diane Von Audrey Matlock Furstenberg The pursuit of personality headquarters is mostly a matter of 440 West 14th façades. -

By Isay Weinfeld

BY ISAY WEINFELD THE PORTUGUESE WORD FOR GARDEN— Jardim—is a fitting name for this private residential enclave overlooking the natural flora of the High Line’s elevated parkland. Designed by celebrated Brazilian architect Isay Weinfeld, two elegantly understated towers, Jardim Norte and Jardim Sul, open to the sun and sky. Lush and tranquil multilevel courtyard gardens are contemplative focal points for Jardim’s 36 one-to-four-bedroom residences. A GROWS IN WEST CHELSEA Jardim Sul | Artist Rendering Weinfeld designs“ the kind of dream residences that prove irresistible, both to Mr. Weinfeld’s popularity“ derives from his style magazines and to use of Brazilian materials and textures, which yield an inviting tropical modernism that serves as an antidote to the chilly other architects, who envy monastic minimalism of recent years. The homes, stores and galleries Mr. Weinfeld their freedom and their designs for influential figures in Brazilian entertainment and fashion are soaring, wide-open spaces in keeping with the country’s seemingly endless spatial famous taste for the bold and beautiful. ‘Architecture must surprise, thrill, cause and formal invention. heart attacks,’ Mr. Weinfeld said. ‘I like to make architecture the same way that João Gilberto sings, that Paul Smith designs clothes, that Caetano Veloso thinks, that my daughter smiles.’ − Edwin Heathcote, Financial Times Magazine − Raul A. Barreneche, The New York Times I SAY WEINFELD BRAZIL-BASED ISAY WEINFELD is a global architect with international appeal. Elegant private residences, luxurious hotels and chic, stylish restaurants across South America, Europe, the Caribbean and the United States—as well as furniture and decorative objects sold in the finest galleries in London, New York and São Paulo—embody Weinfeld’s timeless Modernist sensibility. -

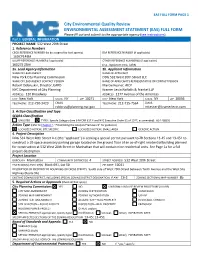

Eas Full Form Page 1

EAS FULL FORM PAGE 1 City Environmental Quality Review ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT STATEMENT (EAS) FULL FORM Please fill out and submit to the appropriate agency (see instructions) Part I: GENERAL INFORMATION PROJECT NAME 532 West 20th Street 1. Reference Numbers CEQR REFERENCE NUMBER (to be assigned by lead agency) BSA REFERENCE NUMBER (if applicable) 16DCP149M ULURP REFERENCE NUMBER (if applicable) OTHER REFERENCE NUMBER(S) (if applicable) 160275 ZSM (e.g., legislative intro, CAPA) 2a. Lead Agency Information 2b. Applicant Information NAME OF LEAD AGENCY NAME OF APPLICANT New York City Planning Commission DDG 532 West 20th Street LLC NAME OF LEAD AGENCY CONTACT PERSON NAME OF APPLICANT’S REPRESENTATIVE OR CONTACT PERSON Robert Dobruskin, Director, EARD Marcie Kesner, AICP NYC Department of City Planning Kramer Levin Naftalis & Frankel LLP ADDRESS 120 Broadway ADDRESS 1177 Avenue of the Americas CITY New York STATE NY ZIP 10271 CITY New York STATE NY ZIP 10036 TELEPHONE 212-720-3423 EMAIL TELEPHONE 212-715-7564 EMAIL [email protected] [email protected] 3. Action Classification and Type SEQRA Classification UNLISTED TYPE I: Specify Category (see 6 NYCRR 617.4 and NYC Executive Order 91 of 1977, as amended): 614.4(b)(9) Action Type (refer to Chapter 2, “Establishing the Analysis Framework” for guidance) LOCALIZED ACTION, SITE SPECIFIC LOCALIZED ACTION, SMALL AREA GENERIC ACTION 4. Project Description DDG 532 West 20th Street LLC (the "applicant") is seeking a special permit pursuant to ZR Sections 13-45 and 13-451 to construct a 10-space accessory parking garage located on the ground floor of an as-of-right residential building planned for construction at 532 West 20th Street in Manhattan that will contain nine residential units. -

Hospitality & Retail

Hospitality & Retail BBB has more than 30 years of planning and design experience in hospitality projects including hotels, clubs, restaurants, and retail — both new construction and renovation. Many of our projects include landmark-designated properties, adaptive reuse of his toric properties as well as a diverse mix of uses. All of our hospitality and retail projects benefit from our keen understanding that brand identity and lifestyle amenities are as critical to success as program and functional requirements. Projects Hospitality 11 Howard Hotel, New York, NY 11 Howard Hotel Hermès ‘21’ Club, New York, NY New York, NY New York, NY 215 Chrystie Street Hotel, New York, NY 220 Eleventh Avenue, New York, NY Double Tree Times Square Feasibility Study, New York, NY Essex House Feasibility Study, New York, NY General Theological Seminary, Desmond Tutu Center and Hotel, New York, NY Natick Collection ‘21’ Club Hilton Times Square, New York, NY Natick, MA New York, NY Hotel 130, New York, NY New York Palace Hotel, New York, NY New York University Torch Club, New York, NY Old Post Office, Washington, DC General Theological Reno Freight House District Restaurants, Reno, NV Seminary: The NYU Torch Club Desmond Tutu Center New York, NY Retail New York, NY 4 Union Square South, New York, NY 42nd Street Development, New York, NY 401 Fifth Avenue - Old Tiffany Building, New York, NY 600 North Michigan Avenue, Chicago, IL Grand Central Hilton Times Square Terminal Ballpark Village, St. Louis, MO New York, NY New York, NY Cartier New York, New York, -

Christie's International Real Estate Opens Its First Ever Real Estate

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Israel Kreps Anthony Tshibangu Kreps DeMaria Luchford APM [email protected] [email protected] +1 305 663 3543 +44 (0)20 7631 1000 Christie’s International Real Estate opens its first ever real estate brokerage gallery space in its flagship New York City auction house Joins forces with real estate industry-leading Erin Boisson Aries team New York, NY (January 18, 2018): For the first time in its 251-year history, Christie’s is opening the doors to a gallery space devoted solely to the sale of luxury residential real estate, working with the industry-leading Erin Boisson Aries team. For more than 20 years, Christie’s, through its wholly owned subsidiary Christie’s International Real Estate, has collaborated with a network of leading real estate brokerages worldwide to represent its clients’ real estate interests. Following a careful buildout process in Christie’s U.S. auction headquarters at 20 Rockefeller Plaza, Christie’s International Real Estate will open the new real estate gallery in a prominent space in the New York City auction house. Christie’s International Real Estate also expects to serve the strategically important Hamptons market with its existing brokerage capabilities and relationships, fortifying its position atop one of the world’s most important luxury markets. Christie’s International Real Estate’s first team of real estate agents will be led by Erin Boisson Aries. Among its industry accolades, the Aries team has achieved the following distinctions in 2017: #1 producer and highest earning -

Historic Preservation BBB Is Well Known for Our Expertise in Restoring, Revitalizing, and Reusing Historic Buildings and Sites

Historic Preservation BBB is well known for our expertise in restoring, revitalizing, and reusing historic buildings and sites. Our project-specific approach is based on research and analysis, a thorough understanding of the cultural context, and the development of appropriate preservation methodologies and new design interventions. We give new life to historic projects through the sensitive and creative integration of contemporary program accommodations, life safety, and infrastructure systems. Cultural Mid-Century Alice Austen House and Grounds Staten Island, NY Marine Air Terminal, LaGuardia Airport Queens, NY Apollo Theater New York, NY Newark Airport, Administration Building Newark, NJ Beacon Theatre New York, NY TWA Flight Center at JFK International Airport Queens, NY Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum New York, NY Preservation Planning Enid A. Haupt Conservatory, New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY Ellis Island New York Harbor General Theological Seminary New York, NY General Theological Seminary New York, NY John Jay Heritage Homestead Rye, NY Governors Island Land Use Study New York, NY Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts New York, NY Governors Island NPS General Management Plan New York, NY Longwood Gardens Kennett Square, PA New York State Canal Recreationway New York State Morgan Library & Museum New York, NY Rockefeller Center New York, NY New-York Historical Society New York, NY Stone Street Master Plan New York, NY New York University, Multiple Projects New York, NY Rubin Museum of Art New York, NY South Street -

Residential the Firm’S Origins Are Rooted in Residential Design

Residential The firm’s origins are rooted in residential design. Our residential projects range from rehabilitation and adaptive reuse of historic buildings, to building additions on top of or adjacent to existing structures, to ground- up new construction. Every building is unique and each floor plan and layout must creatively and pragmatically address a site’s specific challenges. Our residential portfolio demonstrates vision, expertise, and flexibility in the service of both elegant contemporary design and preservation of architectural heritage. Clients 100 Eleventh Avenue Central Place New York, NY Rosslyn, VA Applied Development Company Arun Bhatia Development Organization The Athena Group, LLC Berkshire Capital, LLC BFC Partners 1055 Wisconsin Avenue Seward Park Site 5 Brandolini Companies Washington, DC New York, NY The Brodsky Organization Capelli Enterprises, Inc. Columbia University Community Preservation Corporation The Cordish Companies 33 East 74th Street The Carlton House New York, NY New York, NY Extell Development Company Forest City Ratner Companies HFZ Capital Ian Schrager Company The JBG Companies 551 West 21st Street The Hendrick L+M Development Partners New York, NY Brooklyn, NY Lowe Enterprises Manhattan School of Music Millennium Partners Peebles Corporation R Squared Real Estate Partners 70 Charlton Street The Hepburn Rockrose Development Corp. New York, NY Washington, DC SR Capital Starrett Corporation/Blackacre Capital Management, LLC Taconic Investment Partners, LLC Telesis Corporation Watchcase Factory 70 Washington Street Tippin Corporation Redevelopment New York, NY Tishman Speyer Properties Sag Harbor, NY Toll Brothers Tower Investments Inc. Two Trees Management Co., LLC Urban Muse West Chelsea Development Partners, LLC Whitkoff Group 100 Eleventh Avenue 100 Eleventh Avenue is a condominium tower overlooking the Hudson River featuring a distinctive, curved curtain wall never before seen in New York City. -

100 Eleventh Avenue New York, New York

100 Eleventh Avenue New York, New York Tyler Graybill | Structural Option Advisor: Professor Thomas Boothby Monday, October 5th 2009 ©archpartners.com Technical Report I Tyler E. Graybill |100 Eleventh Avenue | New York, New York Structural Option | Professor T. Boothby 10/05/09 Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 4 Structural System Overview Foundations ............................................................................................................................ 5 Gravity System ........................................................................................................................ 6 Lateral System ....................................................................................................................... 12 Code Design & Standards ........................................................................................................ 13 Material Summary .................................................................................................................... 13 Building Loads Gravity .................................................................................................................................. 14 Lateral .................................................................................................................................. -

Download Design for Higher Education Brochure

Design for Higher Education Educational institutions are complex communities that resonate with BBB’s inquisitive culture. Our planning and design for educational institutions are based on a commitment to understanding the mission and responding to the unique physical, historical, and cultural context of each campus. Our academic projects are attentive to the particularities of program, while also creative and flexible to accommodate evolving pedagogies and the dynamics of campus life. Methodology The demands on academic facilities have never been greater. Often a building is expected to fulfill goals beyond its program — recruiting and retaining the best student and faculty talent, reinventing campus identity, and welcoming community and business partnerships, to name a few. In response to evolving pedagogical models and technology, an increasing emphasis on interdisciplinary study and research, and the transformation of many campuses We are constantly engaging with clients and end-users into living-learning environments, a more intensive, more flexible, and more for a truly collaborative process. creative approach to academic design is required. And these objectives must be achieved within increasingly tight budget and scheduling parameters. Beyer Blinder Belle’s success in meeting these challenges is Academic projects tend to be complex, with many institutional voices seeking to guide them. built on a philosophy of engagement, analysis, and creativity. At no time is collaboration and consensus more important than during the programming phase, when we come to understand our client’s expectations for a building. These discussions must go beyond the determination of quantitative needs in order to understand how the space will support teaching, learning, working, and gathering.