Mary Magdalene Is Now Missing: a Corrected

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lost Tomb of Jesus”

The Annals of Applied Statistics 2008, Vol. 2, No. 1, 1–2 DOI: 10.1214/08-AOAS162 © Institute of Mathematical Statistics, 2008 EDITORIAL: STATISTICS AND “THE LOST TOMB OF JESUS” BY STEPHEN E. FIENBERG Carnegie Mellon University What makes a problem suitable for statistical analysis? Are historical and reli- gious questions addressable using statistical calculations? Such issues have long been debated in the statistical community and statisticians and others have used historical information and texts to analyze such questions as the economics of slavery, the authorship of the Federalist Papers and the question of the existence of God. But what about historical and religious attributions associated with informa- tion gathered from archeological finds? In 1980, a construction crew working in the Jerusalem neighborhood of East Talpiot stumbled upon a crypt. Archaeologists from the Israel Antiquities Author- ity came to the scene and found 10 limestone burial boxes, known as ossuaries, in the crypt. Six of these had inscriptions. The remains found in the ossuaries were re- buried, as required by Jewish religious tradition, and the ossuaries were catalogued and stored in a warehouse. The inscriptions on the ossuaries were catalogued and published by Rahmani (1994) and by Kloner (1996) but there reports did not re- ceive widespread public attention. Fast forward to March 2007, when a television “docudrama” aired on The Dis- covery Channel entitled “The Lost Tomb of Jesus”1 touched off a public and reli- gious controversy—one only need think about the title to see why there might be a controversy! The program, and a simultaneously published book [Jacobovici and Pellegrino (2007)], described the “rediscovery” of the East Talpiot archeological find and they presented interpretations of the ossuary inscriptions from a number of perspectives. -

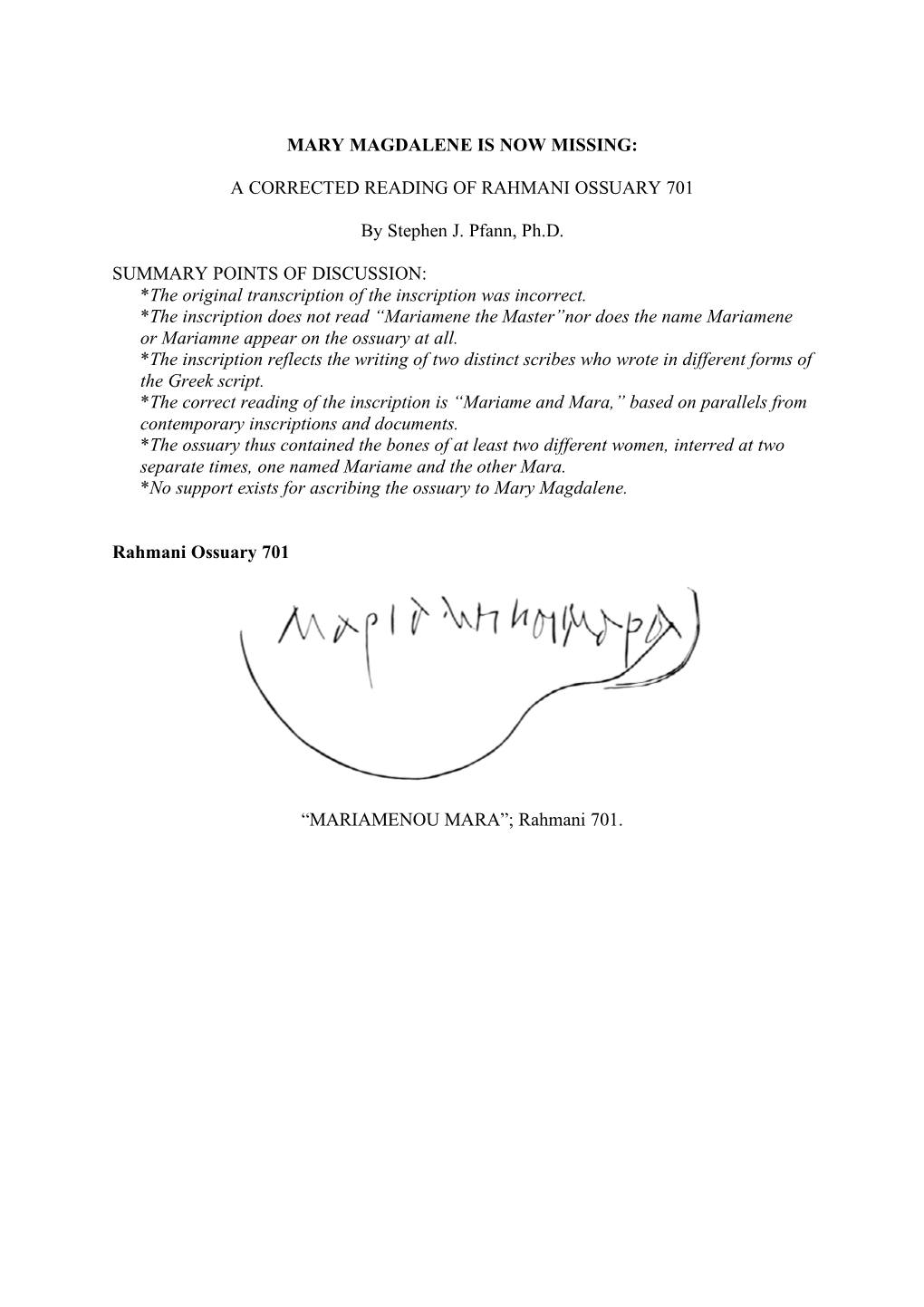

Talpiot Tomb Analysis Sjp3a

1 Demythologyzing the Talpiot Tomb: The Tomb of Another Jesus, Mary and Joseph By Stephen Pfann, Ph.D. University of the Holy Land [Pl. 1: Photo of Tabor, Jacobovici, Cameron with CJO 701 and 704] The 2007 documentary on the Talpiot Tomb produced by Simcha Jacobovici and James Cameron in cooperation with professor of religion James Tabor, superimposed the faces of Mary Magdalene, Jesus and Mary the mother of Jesus on the the tomb's ossuaries including those pictured above. This image has captured the imagination of many by attaching the identity of the first century's most famous family to these ossuaries. The documentaryʼs claim that these ossuaries can be identified as those of Jesus and his family is based on the following assumptions: 1) the cluster of names found in the tomb includes the names Joseph, Mary, Jesus and Joseh makes this tomb statistically significant; 2) finding an ossuary a Jesus son of Joseph and, perhaps more importantly of a "Mary also called Mara", perported to be Mary Magdalene, providing the "Ringo", the linch pin, that forms the basis of an astounding hypothesis. 3) the existence of other followers of Jesus, including Simon Peter, in Jerusalem's necropolis increases the likelihood that Jesus' family tomb appropriately belongs in the same area. According to the hypothesis built upon these premises, it would be extremely unlikely if it was the tomb of anyone other than the central character of the New Testament, Jesus of Nazareth and his family. However, marshalling in the inscriptional evidence on names at our disposal from the Catalogue of Jewish Ossuaries and Dominus Flavit it becomes clear that these names are far from unique, in fact they are among the 1st century Jewish worldʼs most common names. -

The Call of the First Disciples, Philip and Nathanael

LTL2: The Ministry Years 1.08 Notes The call of the first disciples, Philip and Nathaniel The Call of the First Disciples, Philip and Nathanael JCV Integrated Text: John 1:43-51 On the next day, Jesus wanted to set out towards Galilee, and He found Philip and Jesus said to him, "Travel with me." Now Philip was from Bethsaida, the same town as Andrew and Peter. Philip found Nathanael, and said to him, “We have found the one that Moses wrote of in the law and the prophets: Jesus the son of Joseph from Nazareth.” But Nathaniel answered, “Can anything good come out of Nazareth?” Philip retorted, “Come and see.” Jesus saw Nathanael coming toward Him, and said about him, “Look at this, genuinely an Israelite in whom there is no trickiness!” Nathanael responded, “How do you know me?” Jesus answered him, “Before Philip called you, when you were under the fig tree, I saw you.” Nathanael started to speak, saying: "Rabbi, you are the Son of God! You are the King of Israel!" Jesus answered and said to him, “You trust me because I told you, ‘I saw you underneath the fig tree?' You will see greater things than these!” And He said to him, “Really truly, I tell you all, from today you will see heaven opened, and the angels of God ascending and descending on the Son of Man.” Introduction These notes are divided into two sections to follow the relatedLTL2 Living The Ministry Years 1.08a/b videos: • Part A – more detail about Philip and Nathanael and their conversation • Part B – the detail of the conversation between Jesus and Nathanael Part A – Philip and Nathanael Jesus has just called Andrew and Simon Peter the day before. -

Exnt05-Herod

Jewish Resurgence Maccabean Hasmonean Herod Herods Herod the Great 1. Herod’s Rise to Power A. Herod’s Rise: From Idumea to Jewish king (134–104) 1. Idumea captured, judaized (John Hyrcanus I) (103–76) 2. Antipas governor of Idumea (Alex. Janneus) (103–76) 3. Antipater governor of Idumea (Alex. Janneus) (60–53) 4. Antipater procurator of Jerusalem (Gabinius) (47) 5. Herod governor of Galilee (Caesar, Antipater) (43) 6. Herod tetrarch of Galilee (Mark Antony) (40) 7. Herod king of Judea (Roman senate) Jewish Resurgence: Herod the Great Herod the Great 1. Herod’s Rise to Power B. Herod’s Dilemma: Both Loved and Hated 1. Herod the Beloved Hellenizer Roman client king, Hellenistic aspirations Huge building projects, generous donations Low unemployment, prosperous times Greatest Hellenizer of all (historical irony) 2. Herod the Hated Idumean Opposed by some, maligned by many Many threats to throne (Hasmonean, etc.) Jewish Resurgence: Herod the Great Herod the Great 2. Herod’s Reign (37–4 B.C.Mattathias) JudasA. Early ReignJonathan (37–27 B.C.Simon) Eleazar John 1. Consolidating power (marries Mariamne) 2.JudasCrisis of Actium,John Hyrcanus 31 B.C. I Matththias AristobulusAntony I (Alexandereast) vs. Octavian Janneus= Salome(west) Alexandra Antony looses, commits suicide John HyrcanusHerod II skillfullyAristobulus wins IIOctavian’s favor 3. Crisis of Mariamne Alexandra = Alexander Antigonus Accused of capital treason, executed AristobulusHerod’s III briefMariamne period of insanity= Herod the Great Jewish Resurgence: Herod the Great Herod the Great 2. Herod’s Reign (37–4 B.C.) A. Early Reign (37–27 B.C.) 1. Consolidating power (marries Mariamne) 2. -

12. Herod, King of the Jews

12. Herod, King of the Jews 12.0 How Did the Hasmonean Dynasty Transition to the Dynasty of Herod? Salome Alexandra (r. 76-69 BCE) Q (d. 69 BCE) Hyrcanus II (r. 69-69 BCE) K (76-69 and 63-41) HP Aristobulus II (r. 69-63 BCE) HP, K (47-40 BCE) E (d. 30 BCE) (d. 49 BCE) Alexandra (d. 27 BCE) ---- m ----- Alexander (d. 49 BCE) Antigonus (r. 40-37 BCE) HP, K (d. 37 BCE) Aristobulus III Mariamne ---- m ------ Herod. (r. 37-4 BCE) K. (d.@4 BCE) No pun intended, the transition had a lot to do with a Jewish princess. In this case it was a Hasmonean princess named Mariamne. Some years before Aristobulus II and his son died rebelling against the Romans, the son Alexander and his wife Alexandra had two children; a son named Aristobulus III and a daughter named Mariamne When Herod became King, he had been betrothed to Mariamne. Since Mariamne’s father was a Hasmonean, even though a rebellious one, Herod hoped that this marriage would give him greater legitimacy in the eyes of those still faithful to the Torah. Herod waited until he became King before marrying Mariamne. Herod also made Mariamne’s brother, Aristobulus III, the High Priest in Jerusalem. A year later, he had him drowned while bathing in a river. It is said, however, that Mariamne was the true love of Herod’s life 12.1 Did Herod the Great Marry? Oh yes! Often! Wife Children 1. Doris Antipater III 2. Mariamne I Alexander, Aristobulus IV, Salampsio (d), Cypros (d) 3. -

6. the Acts of Philip

6. The Acts of Philip The Acts of Philip is an extensive collection of loosely connected epi- sodes1. However, it is possible to identify four cycles within the mate- rial: chapters 1–2, 3–7, 8–14, and chapter 15 with the martyrdom2. A part of the text is extant in two versions, a shorter and a longer one. This is the case with chapters 3 and 8, where the two commission nar- ratives are found3. There is no commission narrative preceding the first act, which relates that Philip was coming from Galilee and raised the son of a widow. The first reference to commission occurs in chapter 3, where a loosely connected sequence of ‘acts’ begins (chs. 3–7). Acts of Philip 3 At the beginning of chapter 3, Philip meets Peter and the disciples ‘in a certain city’, and addresses them in the following way4: 1. The Greek Acts of Philip contains fifteen ‘acts’ plus the martyrdom text, of which acts 11-15 (whose existence was indicated by the title of a known recen- sion) were found only in 1974 by F. Bovon and B. Bouvier, cf. Bovon, ‘Actes de Philippe’, 4434 and ‘Editing’, esp. 12–3. Chapter 10 is still missing, and some others (11, 14, 15) are fragmentary. Bovon, ‘Actes de Philippe’, 4467, dates the composition of the fifteen acts to the end of the fourth century. De Santos Otero, ‘Acta Philippi’, 469, situates the Acts of Philip ‘in encratite circles in Asia minor somewhere about the middle of the 4th century’. Amsler, Actes de l’apôtre Phil- ippe, 80, calls it a ‘first hand document’ (except for the second ‘act’) of the Asian encratic milieu on the turn of the fourth and fifth centuries. -

Flavius Josephus the ANTIQUITIES of the JEWS :Index

Flavius Josephus THE ANTIQUITIES OF THE JEWS :Index. Flavius Josephus THE ANTIQUITIES OF THE JEWS General Index ■ PREFACE. ■ BOOK I: CONTAINING THE INTERVAL OF THREE THOUSAND EIGHT HUNDRED AND THIRTY-THREE YEARSFROM THE CREATION TO THE DEATH OF ISAAC ■ BOOK II: CONTAINING THE INTERVAL OF TWO HUNDRED AND TWENTY YEARSFROM THE DEATH OF ISAAC TO THE EXODUS OUT OF EGYPT ■ BOOK III: CONTAINING THE INTERVAL OF TWO YEARSFROM THE EXODUS OUT OF EGYPT, TO THE REJECTION OF THAT GENERATION ■ BOOK IV: CONTAINING THE INTERVAL OF THIRTY-EIGHT YEARSFROM THE REJECTION OF THAT GENERATION TO THE DEATH OF MOSES ■ BOOK V: CONTAINING THE INTERVAL OF FOUR HUNDRED AND SEVENTY-SIX YEARSFROM THE DEATH OF MOSES TO THE DEATH OF ELI ■ BOOK VI: CONTAINING THE INTERVAL OF THIRTY-TWO YEARSFROM THE DEATH OF file:///D|/Documenta%20Chatolica%20Omnia/99%20-%20Pro...y/001%20-Da%20Fare/01/0-JosephusAntiquitiesOfJews.htm (1 of 3)2006-05-31 19:49:21 Flavius Josephus THE ANTIQUITIES OF THE JEWS :Index. ELI TO THE DEATH OF SAUL ■ BOOK VII: CONTAINING THE INTERVAL OF FORTY YEARSFROM THE DEATH OF SAUL TO THE DEATH OF DAVID ■ BOOK VIII: CONTAINING THE INTERVAL OF ONE HUNDRED AND SIXTY-THREE YEARSFROM THE DEATH OF DAVID TO THE DEATH OF AHAB ■ BOOK IX: CONTAINING THE INTERVAL OF ONE HUNDRED AND FIFTY-SEVEN YEARSFROM THE DEATH OF AHAB TO THE CAPTIVITY OF THE TEN TRIBES ■ BOOK X: CONTAINING THE INTERVAL OF ONE HUNDRED AND EIGHTY-TWO YEARS AND A HALFFROM THE CAPTIVITY OF THE TEN TRIBES TO THE FIRST YEAR OF CYRUS ■ BOOK XI: CONTAINING THE INTERVAL OF TWO HUNDRED AND FIFTY-THREE YEARS AND -

The Herodian Family Tree

The Family Tree of the Herodian Dynasty Siblings of Herod the Great Wives of Herod the Great LEGEND Male individuals Pheroras Phasael Salome I Herod the Great Mariamne I Mariamne II Malthace Cleopatra of Jerusalem Female individuals 68? – 5 BCE Before 73 – 40 BCE c. 65 BCE – 10 CE 73/74 – 4 BCE (Mariamne the Hasmonean) ? – ? (Malthace the Samaritan) ? – ? BCE Individuals without their own entry 54 – 29 BCE ? – 4 BCE Father: Simon Boethus (high priest) Father: ? References in ancient sources Tetrarch of Perea 20 – 5 BCE Governor of Jerusalem 47? – 41 BCE Toparch of Jabneh, Ashdod, & Phasaelis Governor of Galilee 47 – 41 BCE Mother: ? Mother: ? 4 BCE – 10 CE Father: Alexander of Judaea Father: ? Historical/literary details Tetrarch of Judaea 41 – 40 BCE Mother: Alexandra Maccabeus Siblings: ? Mother: ? Siblings: ? Father: An#pater the Idumaean Tetrarch of Galilee 41 – 40 BCE Paternal relationship Mother: Cypros Father: An#pater the Idumaean Siblings: Aristobulus III Siblings: ? Marriages and children: Father: An#pater the Idumaean Marriages and children: Siblings: Herod the Great, Salome I, Joseph, Mother: Cypros King of Judaea Herod the Great — Philip Maternal relationship Mother: Cypros Marriages and children: Herod the Great — Herod II Marriages and children: Phasael Siblings: Herod the Great, Phasael, Joseph, 40/39 BCE – 4 BCE Herod the Great — Alexander, Aristobulus Herod the Great — Archelaus, An1pas, Marital relationship Siblings: Herod the Great, Salome I, Joseph, Pheroras Josephus: JW 1.561 Josephus: JW 1.561, Ant 17.1.3 IV, Salampsio, Cypros II Olympias Marriages and children: Pheroras Father: An#pater the Idumaean Divorced by Herod in 4 BCE. Born and raised in Jerusalem. -

The Acts of Philip

From "The Apocryphal New Testament" M.R. James-Translation and Notes Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1924 Introduction No such suspicion of unorthodoxy as -rightly or wrongly- attaches to four out of the Five Acts, affects the Acts of Philip. If grotesque, it is yet a Catholic novel. In form it follows Thomas, for it is divided into separate Acts, of which the manuscripts mention fifteen: we have Acts i-ix and from xv to the end, including the Martyrdom, which last, as usual, was current separately and exists in many recessions. One Act -the second- and the Martyrdom were first edited by Tischendorf. Batiffol printed the remainder in 1890, and Bonnet using more manuscripts, gives the final edition in his Acta Apost. Apocr. ii. 1. Besides the Greek text, there is a single Act extant only in Syriac, edited by Wright, which, so far as its general character goes, might well have formed part of the Greek Acts: but it is difficult to fit it into the framework. An analysis, with translations of the more interesting passages, will suffice for these Acts, and for the rest of their class. I. When he came out of Galilee and raised the dead man. 1 When he was come out of Galilee, a widow was carrying out her only son to burial. Philip asked her about her grief: I have spent in vain much money on the gods, Ares, Apollo, Hermes, Artemis, Zeus, Athena, the Sun and Moon, and I think they are asleep as far as I am concerned. And I consulted a diviner to no purpose. -

Philip, the Apostle

The Apostle Philip Including Narcissus of the Seventy and Joseph of Arimathea November 14, 2020 GOSPEL: John 1:43-51 EPISTLE: 1 Corinthians 4:9-16 Philip’s Early Life Philip was born in Bethsaida, as were Peter and Andrew, (John 1:44, 12:21) and was instructed in the Scriptures from his youth. Philip was a follower of John the Baptist, as was his friend, Nathanael of Cana (John 21:2). As followers of John, Philip and Nathanael did a lot of prayer and fasting, as John taught his disciples to do (Mark 2:18-22, Luke 11:1-13). This may have been what Nathanael was doing when Jesus “saw him under the fig tree” (John 1:48). John Chrysostom stated1 that Philip’s association with John the Baptist was no small preparation for his Apostleship with Christ. The Scriptures do not mention whether or not Philip was among the fishermen of the Apostles (John 21:1-3). It was customary for all Jewish boys to learn a trade as part of their education, and Philip needed to work at his trade to support his family, which included several young children at the time Jesus called him. John Chrysostom commented2 that the lack of background information on the Twelve Apostles was not a big deal: “And why, one may say, has he not told us how and in what manner the others were called; but only of Peter and Andrew, James and John, and Philip and Matthew? Because these lived such a humble way of life, more than others! There is nothing worse than the publican’s business, or more ordinary than fishing. -

Jesus Family Tomb”

Evidence Real and Imagined: Thinking Clearly About the “Jesus Family Tomb” Michael S. Heiser, PhD Academic Editor, Logos Bible Software On March 4, 2007, the Discovery Channel aired “The Lost Tomb of Jesus,” a riveting documentary produced by James Cameron, best known for the Oscar-winning motion picture Titanic, and directed by Simcha Jacobovici. The documentary complemented the launch of the publicity campaign for a book on the subject by Jacobovici, co-authored with Charles Pellegrino, entitled The Jesus Family Tomb (Harper San Francisco). The two-hour special focused on the 1980 discovery of what appears to be a family tomb located in East Talpiot, Jerusalem. The tomb housed ten ossuaries (bone boxes), several of which bore inscribed names intimately associated with Christianity, including Jesus, Mary, and Joseph. Jacobovici claims that one of ossuaries should be identified as that of Mary Magdalene, whose inclusion in the family tomb of Jesus proves that she and Jesus were married. For Jacobovici and his associates, the find constitutes proof that Jesus had not risen from the dead as the New Testament describes.1 Not surprisingly, the documentary of Cameron and Jacobovici has caused quite a stir. If their interpretation is correct, the Talpiot tomb discovery is arguably the most important archaeological find of the last two thousand years and effectively invalidates Christianity as western civilization has known it during those two millennia. But are they right? Does the world now have proof that traditional Christianity has been little more than a historical contrivance? In what follows we will describe the data, the claims derived from them, and their analysis by Jacobovici and his colleagues, demonstrating that both the book and the documentary obscure or omit critical interpretive issues for accurately assessing the data, and frequently build their case through speculation about data that does not exist. -

Herod the Great Herod the Great, Was a Roman Client King of Judea, Referred to As the Herodian Kingdom

Herod the Great Herod the Great, was a Roman client king of Judea, referred to as the Herodian kingdom. The history of his legacy has polarized opinion, as he is known for his colossal building projects throughout Judea, including his renovation of the Second Temple in Jerusalem and the expansion of the Temple Mount towards its north, the Tomb of the Patriarchs in Hebron, the construction of the port at Caesarea Maritima, the fortress at Masada, and Herodium. Vital details of his life are recorded in the works of the 1st century CE Roman–Jewish historian Josephus. Herod also appears in the Christian Gospel of Matthew as the ruler of Judea who orders the Massacre of the Innocents at the time of the birth of Jesus, although a majority of Herod biographers do not believe this event to have occurred. Despite his successes, including singlehandedly forging a new aristocracy from practically nothing, he has still garnered criticism from various historians. His reign polarizes opinion amongst scholars and historians, some viewing his legacy as evidence of success, and some as a reminder of his tyrannical rule. Upon Herod's death, the Romans divided his kingdom among three of his sons and his sister: Archelaus became ethnarch of Judea, Samaria, and Idumea; Herod Antipas became tetrarch of Galilee and Peraea; Philip became tetrarch of territories north and east of the Jordan; and Salome I was given a toparchy including the cities of Jabneh, Ashdod, and Phasaelis. Biography It is generally accepted that Herod was born around 73 BCE in Idumea, south of Judea.