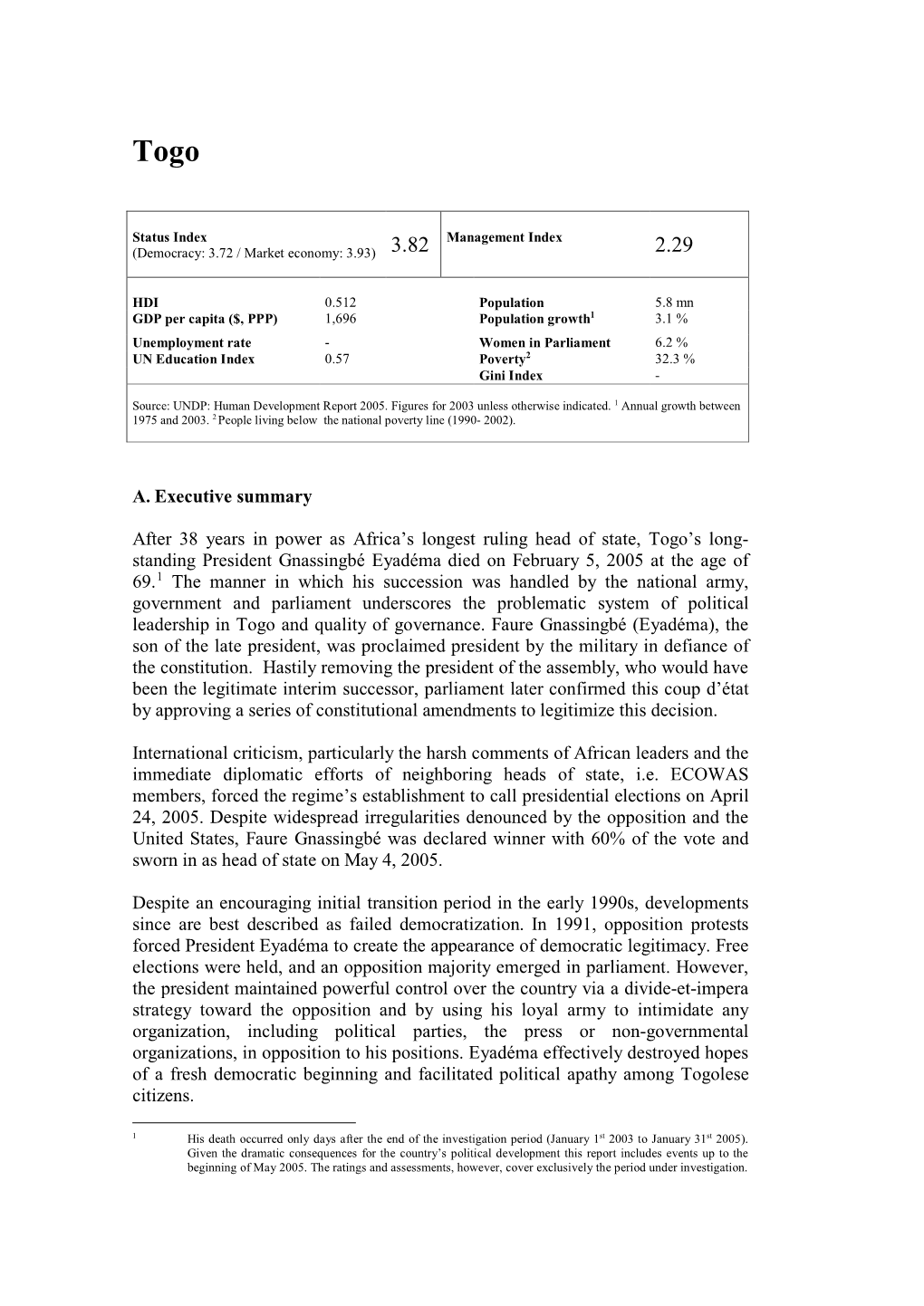

BTI 2006 Togo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO

Assessing the of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO REPORT 3/2019 Publisher: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs Copyright: © Norwegian Institute of International Affairs 2019 ISBN: 978-82-7002-346-2 Any views expressed in this publication are those of the author. Tey should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. Te text may not be re-published in part or in full without the permission of NUPI and the authors. Visiting address: C.J. Hambros plass 2d Address: P.O. Box 8159 Dep. NO-0033 Oslo, Norway Internet: effectivepeaceops.net | www.nupi.no E-mail: [email protected] Fax: [+ 47] 22 99 40 50 Tel: [+ 47] 22 99 40 00 Assessing the Efectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC (MONUC-MONUSCO) Lead Author Dr Alexandra Novosseloff, International Peace Institute (IPI), New York and Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), Oslo Co-authors Dr Adriana Erthal Abdenur, Igarapé Institute, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Prof. Tomas Mandrup, Stellenbosch University, South Africa, and Royal Danish Defence College, Copenhagen Aaron Pangburn, Social Science Research Council (SSRC), New York Data Contributors Ryan Rappa and Paul von Chamier, Center on International Cooperation (CIC), New York University, New York EPON Series Editor Dr Cedric de Coning, NUPI External Reference Group Dr Tatiana Carayannis, SSRC, New York Lisa Sharland, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Canberra Dr Charles Hunt, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) University, Australia Adam Day, Centre for Policy Research, UN University, New York Cover photo: UN Photo/Sylvain Liechti UN Photo/ Abel Kavanagh Contents Acknowledgements 5 Acronyms 7 Executive Summary 13 Te effectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC across eight critical dimensions 14 Strategic and Operational Impact of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Constraints and Challenges of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Current Dilemmas 19 Introduction 21 Section 1. -

Togo an Election Tainted by Escalating Violence

Public amnesty international TOGO AN ELECTION TAINTED BY ESCALATING VIOLENCE AI Index: AFR 57/005/2003 6 June 2003 INTERNATIONAL SECRETARIAT, 1 EASTON STREET, LONDON WC1X 0DW, UNITED KINGDOM TOGO : AN ELECTION TAINTED BY ESCALATING VIOLENCE The presidential election that took place in Togo on 1 June 2003 resulted, as many independent observers feared, in clashes between opposition supporters and the security forces, who made arrests and used force to suppress demonstrations and discontent in several parts of the country. During the last month, the security forces have arrested about forty people who the military suspect of voting for opposition candidates or inciting other people to do so. One person was shot in the back in an extrajudicial manner by a member of the security forces. The man was escaping on a motor bike when he was shot. Another person was seriously wounded in this incident. Security forces are on patrol throughout the country, especially in Lomé. Passers-by, some of whom were suspected of being close to the opposition, have been stopped in the street by the security forces and beaten up. The authorities have also put pressure on journalists to publish only the results announced by the Commission électorale nationale indépendante (CENI) 1 , National Independent Electoral Commission. On 4 June 2003, CENI officially declared the winner of the election to be the outgoing president, Gnassingbé Eyadéma, in power since 1967. Two days previously, two opposition candidates, Emmanuel Bob Akitani and Maurice Dahuku Péré, representatives, of l’Union des forces du changement (UFC) the Union of Forces for Change and the Pacte socialiste pour le renouveau (PSR), Socialist Pact for Renewal respectively, proclaimed themselves winners of the election. -

The Chair of the African Union

Th e Chair of the African Union What prospect for institutionalisation? THE EVOLVING PHENOMENA of the Pan-African organisation to react timeously to OF THE CHAIR continental and international events. Th e Moroccan delegation asserted that when an event occurred on the Th e chair of the Pan-African organisation is one position international scene, member states could fail to react as that can be scrutinised and defi ned with diffi culty. Its they would give priority to their national concerns, or real political and institutional signifi cance can only be would make a diff erent assessment of such continental appraised through a historical analysis because it is an and international events, the reason being that, con- institution that has evolved and acquired its current trary to the United Nations, the OAU did not have any shape and weight through practical engagements. Th e permanent representatives that could be convened at any expansion of the powers of the chairperson is the result time to make a timely decision on a given situation.2 of a process dating back to the era of the Organisation of Th e delegation from Sierra Leone, a former member African Unity (OAU) and continuing under the African of the Monrovia group, considered the hypothesis of Union (AU). the loss of powers of the chairperson3 by alluding to the Indeed, the desirability or otherwise of creating eff ect of the possible political fragility of the continent on a chair position had been debated among members the so-called chair function. since the creation of the Pan-African organisation. -

Export Agreement Coding (PDF)

Peace Agreement Access Tool PA-X www.peaceagreements.org Country/entity Togo Region Africa (excl MENA) Agreement name Dialogue inter-togolais: accord cadre de Lomé Date 27/09/1999 Agreement status Multiparty signed/agreed Interim arrangement No Agreement/conflict level Intrastate/intrastate conflict ( Togolese Conflicts (1946 - ) ) Stage Framework/substantive - partial (Core issue) Conflict nature Government Peace process 118: Togo peace process Parties For the Presidential Office: the Gathering of the Togolese People (RPT) the Convention of the New Forces (CFN) Professor Fambaré Ouattara Natchaba, RPT member of the Political Bureau For the Committee of Action for Renewal (CAR) Yawovi Agboyibo, National President For Convention African Peoples Democratic (FDC) Mr. Leopold Gnininvi, Secretary General For Party for Democracy and Renewal (PDR) Monseiur Zarifou Ayeva, President For the Union of Forces for Change (UFC) Mr. Emmanuel Akitani Bob, First Vice President For the Togolese Union for Democracy (UTD) the Party of the pure-Action on Development (PAD) Democratic party pure Unite (PDU) the Union for the Democracy and Solidarity (UDS) Mr. Edem Kodjo, President Third parties The Facilitators; For the EU, Georg Reisch, For the International Organization of Francophonie, Moustapha Niasse, For the Republic of France, Bernard Stasi, For the Republic of Germany, Paul von Stulpnagel, Description Following the political crises in Togo the EU, France, Germany, and the international organisation of Francophonie were asked to facilitate an inter-Togolese dialogue which started on July 19, 1999 in Lomé. The different parties agreed the agenda and presented their viewpoints and proposals. The facilitators drafted a summary of the debates and a list of the points on which agreement was found. -

Togo Fact Sheet

Togo – Fact Sheet Official Name Republic of Togo Capital Lome 56.790sq.kms Area Currency CFA Franc (Community Financial African Franc) US1D 1=CFA 545 ;INR 1=7.4011 CFA(October 2020) GDP USD 5.46 billion(2020-WTO) GDP Growth Rate 2.1%(Marc 2020) Composition of GDP agriculture: 28.8% (2017 est.) industry: 21.8% (2017 est.) services: 49.8% (2017 est.) GDP Per Capita USD 695.90(Nominal)(2019-World Bank) Togo recorded a government debt equivalent to 29.50 Debt to GDP percent of the country's Gross Domestic Product in 2019.(according to Tradingeconomics.com/BCEAO) Inflation 2.9%(sep-2020) Unemployment 1.7%(Dec 2019) Forest Cover just 7% of total land area in 2010) CO2 emisions 0.40 mtpc(2016) Togo carbon (co2) emissions for 2016 was 2,999.61, a 13.77% increase from 2015. Tourist Arrivals International tourism, number of arrivals in Togo was reported at 573000 in 2018, according to the World Bank Population 7.80 million (Male-3.89 mn ;Female-3.91, mn-2017- UN) Life expectancy 60 years(2016) Languages French ;Major local dialects-Ewe,Mina,Kabye and Dagomba Native Africans constitute 99% of Togo's total Ethnic group population. Some 37 tribal groups comprise a mosaic of peoples possessing neither language nor history in common. The main ethnic group consists of the Ewe and such related peoples as the Ouatchi, Fon, and Adja; they live in the south and constitute at least 40% of the population. Next in size are the Kabrè and related Losso living in the north. -

Togo: Thorny Transition and Misguided Aid at the Roots of Economic Misery

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Togo: Thorny transition and misguided aid at the roots of economic misery Kohnert, Dirk GIGA - Institute of African Affairs, Hamburg 8 October 2007 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/9060/ MPRA Paper No. 9060, posted 13 Jun 2008 10:14 UTC GIGA Research Programme: Transformation in the Process of Globalisation Togo: Failed transition and misguided aid at the roots of economic misery1 Dirk Kohnert October 2007 Abstract The holding of early parliamentary elections in Togo on October 14, 2007, most likely the first free and fair Togolese elections since decades, are considered internationally as a litmus test of despotic African regimes’ propensity to change towards democratization and economic prosperity. Western donors took Togo as model to test their approach of political conditionality of aid, which had been emphasised as corner stone of the joint EU-Africa strategy. Recent empirical findings on the linkage between democratization and economic performance are challenged in this paper. It is open to question, whether Togo’s expected economic consolidation and growth will be due to democratization of its institutions or to the improved external environment, notably the growing competition between global players for African natural resources. Key words: democratization, governance, economic growth, development, LDCs, Africa JEL Code: F35 - Foreign Aid; F51 - International Conflicts; Negotiations; Sanctions; F59 - International Relations and International Political Economy; O17 - Formal and Informal Sectors; Shadow Economy; Institutional Arrangements; O55 – Africa; P47 - Performance and Prospects; P48 - Political Economy; Legal Institutions; Property Rights; Z1 - Cultural Economics; Economic Sociology Dr. Dirk Kohnert is economist and Deputy Director of the Institute of African Affairs (IAA) at GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies in Hamburg, Germany, and editor of the scholarly journal ‘Afrika Spectrum’ since 1991. -

L'o.U.A. : Rétrospective Et Perspectives Africaines La Vie Du Droit En Afrique

L'O.U.A. : RÉTROSPECTIVE ET PERSPECTIVES AFRICAINES LA VIE DU DROIT EN AFRIQUE Collection dirigée par Gérard CONAC BOUREL Pierre Droit de la famille au Sénégal CONAC Gérard (sous la direction de) * Dynamiques et finalités des droits africains * Les institutions administratives des Etats francophones d'Afrique noire * Les institutions constitutionnelles des Etats francophones d'Afrique noire (épuisé) * Les grands services publics dans les Etats francophones d'Afrique noire * Les cours suprêmes et les hautes juridictions des Etats d'Afrique - 2 tomes (à paraître) CONAC Gérard, SAVONNET-GUYOT Claudette, CONAC Françoise (sous la direction de) Les Politiques de l'eau en Afrique LAMINE Sidime L'établissement de la filiation en droit sénégalais depuis le Code de la famille MESCHERIAKOFF Alain-Serge Le droit administratif ivoirien SARASSORO Hyacinthe La corruption des fonctionnaires en Afrique (épuisé) TJOUEN Alexandre-Dieudonné Droits domaniaux et techniques foncières en droit camerounais COOPÉRATION CONAC Gérard, DESOUCHES Christine, SABOURIN Louis (sous la direction de) La coopération multilatérale francophone (1987) La Vie du Droit en Afrique Collection dirigée par Gérard Conac Maurice KAMTO Professeur Agrégé des Facultés de Droit, Université de Yaoundé (IRIC) Jean-Emmanuel PONDI Laurent ZANG Ph. D. en Science Politique Docteur ès Science Politique Chargé de Cours à l'IRIC Chargé de Cours à l'IRIC L'O.U.A. : RÉTROSPECTIVE ET PERSPECTIVES AFRICAINES Avec la collaboration de DODO BOUKARI A. KARIMOU, Camille NKOA ATENGA et David SINOU ik .' i 'o ^- > Préface de M. Boutros BOUTROS-GHALI Professeur Honoraire à l'Université du Caire Ministre d'Etat aux Affaires Etrangères ECONOMICA 49, rue Héricart, 75015 Paris \ ^v^J^d^tONOMICA, 1990 Tous droits de repr 1 , de traduction, d'adaptation et d'exécution réservés pour tous les pays. -

Drugs, the State and Society in West Africa

NOT JUST IN TRANSIT Drugs, the State and Society in West Africa An Independent Report of the West Africa Commission on Drugs June 2014 ABOUT THE COMMISSION Deeply concerned by the growing threats of drug trafficking and consumption in West Africa, Kofi Annan, Chair of the Kofi Annan Foundation and former Secretary-General of the United Nations, convened the West Africa Commission on Drugs (WACD) in January 2013. The Commission’s objectives are to mobilise public awareness and political commitment around the challenges posed by drug trafficking; develop evidence- based policy recommendations; and promote regional and local capacity and ownership to manage these challenges. Chaired by former President Olusegun Obasanjo of Nigeria, the Commission comprises a diverse group of West Africans from the worlds of politics, civil society, health, security and the judiciary. The Commission is an independent body and can therefore speak with impartiality and directness. This report is the culmination of one and a half years of engagement by the Commission with national, regional and international parties including the African Union (AU), the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). It is informed by a series of background papers, drafted by leading experts from Africa and beyond.1 Olusegun Obasanjo (Chair) (Nigeria) Former President of Nigeria Dr. Idrissa Ba Justice Bankole- Dr. Mary Chinery- Dr. Alpha Abdoulaye Christine Kafando (Senegal) Thompson Hesse Diallo (Burkina Faso) Child psychiatrist and (Sierra Leone) (Ghana) (Guinea) Founder, Association addictologist, Psychiatric Former Judge on the Member of the African National Coordinator, Espoir pour Demain Hospital of Thiaroye, Special Court for Sierra Union Panel of the Wise Réseau Afrique Dakar Leone Jeunesse Edem Kodjo Dr. -

Rapport De La Mission Francophone D'observation Des Elections Legislatives Du 14 Octobre 2007 Au Togo

RAPPORT DE LA MISSION FRANCOPHONE D’OBSERVATION DES ELECTIONS LEGISLATIVES DU 14 OCTOBRE 2007 AU TOGO Octobre 2007 Délégation à la Paix, à la Démocratie et aux droits de l’Homme INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 4 A. GENESE DE LA MISSION......................................................................................................... 4 B. COMPOSITION DE LA MISSION.............................................................................................. 6 C. ORGANISATION ET CADRE DE TRAVAIL DE LA MISSION ................................................. 7 I. SITUATION POLITIQUE GENERALE ............................................................................................ 9 A. CADRE GENERAL .................................................................................................................. 10 1. Quelques chiffres............................................................................................................... 10 2. La situation politique ......................................................................................................... 10 2.1. Les différents scrutins législatifs au Togo...................................................................... 11 a. Les scrutins du 6 et 20 février 1994 ................................................................................. 11 b. Le scrutin du 21 mars 1999.............................................................................................. -

Inter-Togolese Dialogue Lome

PA-X, Peace Agreement Access Tool (Translation © University of Edinburgh) www.peaceagreements.org INTER-TOGOLESE DIALOGUE LOME FRAMEWORK AGREEMENT (ACCORD CADRE DE LOMÉ, ACL) PREAMBLE For years Togo has been in serious political crisis, with worsening economic and social circumstances following the suspension of cooperation with a number of other States. On November 20, 1998, the Leader convened a meeting of the various political forces in order to define the process for a national dialogue to overcome the crisis. On December 24, the President’s party and all the opposition parties agreed that Facilitators should help the Togolese to establish the conditions needed for a calm and constructive dialogue between the country’s political forces. In response to this reQuest, the European Union, France, Germany, and the International Organisation of La Francophonie nominated four persons to carry out this facilitation mission. CONTENT OF THE NEGOTIATIONS The parties involved have, by common agreement, prepared an agenda for the negotiations based on the proposals of the President’s party and of the opposition parties (attached in annex). The following conclusions were reached during discussion of the different agenda points: The first objective agreed by the Togolese parties is to create a reciprocal climate of confidence, for the benefit of national reconciliation. Indeed, all of the parties are clear that the proper and regular functioning of Togolese institutions depend on this. All of the parties stated their commitment to democracy, the rule of law, respect for Human Rights, development and security for all. 1 PA-X, Peace Agreement Access Tool (Translation © University of Edinburgh) www.peaceagreements.org There was discussion of the following themes: RESPECT FOR THE CONSTITUTION AND CONDITIONS FOR POLITICAL ALTERNATION Strict respect for the Constitution of the Fourth Togolese Republic and the proper functioning of all its institutions are essential reQuirements for free democracy and political alternation. -

(La Commission De L'union Africaine (UA) a Nommé L'ex Premier Togolais

(La commission de l’Union Africaine (UA) a nommé l’ex Premier togolais Edem Kodjo en République Démocratique du Congo (RDC) comme facilitateur en vue de mener les consultations pour le dialogue politique. ) BURUNDI : RWANDA : RDC CONGO : RD Congo: Edem Kodjo nommé pour relever le défi du dialogue koaci. com/Lundi 18 Janvier 2016 © koaci. com– Lundi 18 Janvier 2016 – La commission de l’Union Africaine (UA) a nommé l’ex Premier togolais Edem Kodjo en République Démocratique du Congo (RDC) comme facilitateur en vue de mener les consultations pour le dialogue politique. En sa qualité de facilitateur de l’UA en RDC, Edem Kodjo devra œuvrer pour un rapprochement des points de vue entre les acteurs de la classe politique ceux l’opposition congolaise. Le dialogue en question est proposé par le Président congolais Joseph Kabila mais ne requiert pas totalement l’assentiment de l’opposition. En attardant d’entamer sa mission, l’ex Secrétaire général de l'Organisation pour l'Unité Africaine (OUA) devra chercher les voies et moyens pour rassembler la classe politique dont les adversaires du Président Joseph Kabila s’opposent à l’idée d’un troisième mandat de l’actuel Chef de l’Etat. Edem Kodjo reprend un dossier complexe en main là ou l’ex envoyé des Nations Unies (ONU), Saïd Djinnit, n’avait pas réussi. Devant l’improductivité de sa mission, le diplomate onusien avait rendu son tablier en juin 2015. Mensah, Lomé UGANDA : SOUTH AFRICA : South Africa Vows to Avoid Downgrade to Junk, Business Day Says January 19, 2016/bloomberg. com South Africa’s government, businesses and labor unions must act together to claw back lost fiscal credibility and avoid a credit-rating downgrade to junk, Business Day reported, citing Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan. -

Constitutional and Succession Crisis in West Africa: the Case of Togo

Constitutional and Succession Crisis in West Africa: The Case of Togo Adewale Banjo* ………………… Abstract The politics of succession in post-independence West Africa has left much to be desired and, by extension, has affected the quality of democracy and human security in the sub-region. This article briefly assesses succession politics in Togo, a small West African nation of approximately 5 million people, following the death of President Gnassingbe Eyadema, one of Africa’s longest serving dictators. The author describes the military takeover and subsequent election that legitimized the illegal take over of power by Eyadema’s son despite sustained domestic opposition from politicians and civil society, as well as sub-regional, regional and international condemnation of a Constitutional “coup d’etat” in Togo. The article concludes that the succession crisis in Togo is far from over, given the continuing manipulation of what the author calls the geo-ethnic divide in that country. ∗Ph.D. (Ibadan), Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, University of Zululand, KZN, South Africa. A former UNESCO Scholar and George Soros/CEU Fellow, he is the author of ‘ECOWAS Court and the Politics of Access to Justice in West Africa’ in Afrique et Developpement, CODESRIA (2007). ©2008. The Africa Law Institute. All rights reserved. Cite as: 2 Afr. J. Legal Stud. 2 (2005) 147-161. The African Journal of Legal Studies (“AJLS”) is a free peer-reviewed and interdisciplinary journal published by The Africa Law Institute (“ALawI”). ALawI’s mission is to engage in policy-oriented research that promotes human rights, good governance, democracy and the rule of law in Africa.