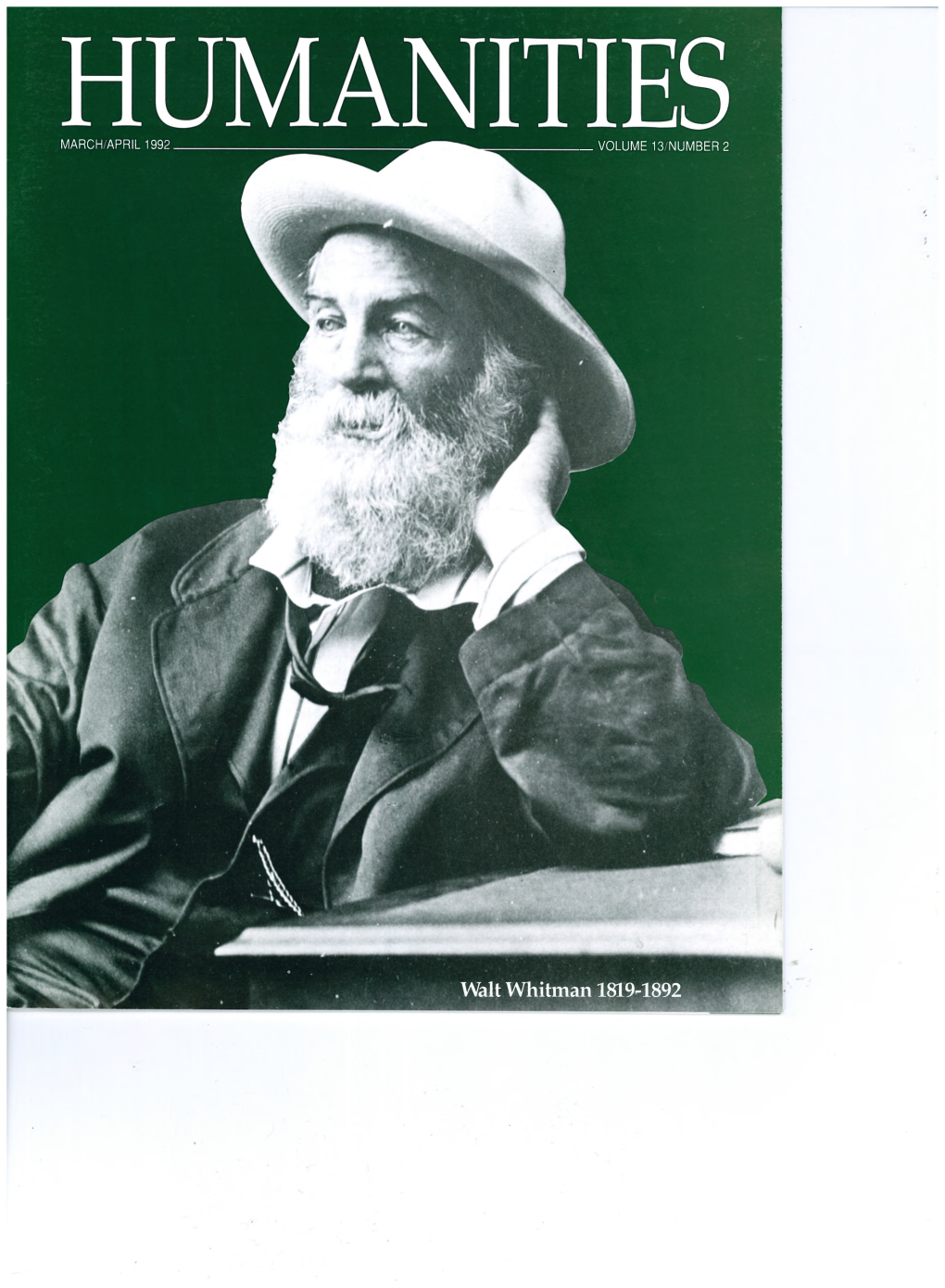

Walt Whitman 1819-1892 EDITOR's NOTE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Finding Aid to the Elihu Vedder Papers, 1804-1969(Bulk 1840-1923), in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Elihu Vedder Papers, 1804-1969(bulk 1840-1923), in the Archives of American Art Jennifer Meehan Funding for the processing and digitization of this collection was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art September 12, 2006 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical Note............................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Miscellaneous Personal Papers, 1811-1938............................................ 5 Series 2: Correspondence, 1804-1951.................................................................... 7 Series 3: Diaries, 1878-1890................................................................................. -

HOMAGE to the SEA Cover: JAMES E

HOMAGE TO THE SEA Cover: JAMES E. BUTTERSWORTH (1817-1894) The Schooner “Triton” and The Sloop “Christine” Racing In Newport Harbor circa 1884 Oil on canvas 12 x 18 inches Signed, lower right HOMAGE TO THE SEA AN EXHIBITION AND SALE OF 18TH, 19TH & 20TH CENTURY AMERICAN MARINE ART TO BENEFIT INTERNATIONAL YACHT RESTORATION SCHOOL (IYRS) & MUSEUM OF YACHTING JULY 11 - SEPTEMBER 14, 2008 WILLIAM VAREIKA FINE ARTS LTD THE NEWPORT GALLERY OF AMERICAN ART 212 BELLEVUE AVENUE • NEWPORT, RHODE ISLAND 02840 WWW.VAREIKAFINEARTS.COM 401-849-6149 There is a tide in the affairs of men, which taken at the flood, leads We are tied to the ocean. And when we go back to the sea, on to fortune. Omitted, all the voyage of their life is bound in whether it is to sail or to watch – we are going back from shallows and in miseries. On such a full sea are we now afloat. whence we came. And we must take the current when it serves, or lose our ventures. John F. Kennedy William Shakespeare Remarks at the America’s Cup Dinner, Brutus, Julius Caesar Newport, RI, September 14, 1962 As we enter our twenty-first summer of operation in our Bellevue Avenue gallery, Alison and I are pleased to offer “Homage to the Sea,” a major exhibition and sale of marine artworks by important 18th, 19th and early 20th century American artists. Continuing our gallery’s two-fold mission to present museum-quality art to the public and to raise funds and consciousness about important non-profit causes, we are pleased to donate a percentage of sales from this endeavor to two deserving Newport institutions in the marine field: the Museum of Yachting and the International Yacht Restoration School (IYRS). -

Pilgrims of Beauty: Art and Inspiration in 19Th-Century Italy, February 3, 2012-July 8, 2012

Pilgrims of Beauty: Art and Inspiration in 19th-Century Italy, February 3, 2012-July 8, 2012 Throughout the 19th century, the landscape, history, architecture, and art of Italy served as a tremendous source of inspiration for artists. Masters such as Ingres, Turner, Sargent, and Whistler were among those who benefitted from, and contributed to, the spirit of artistic experimentation and collaboration Italy offered. Featuring more than 60 works of art--including paintings, sculpture, drawings, prints, photographs, and jewelry, all drawn from the Museum's permanent collection--Pilgrims of Beauty is a window into the array of styles and approaches that emerged from Italy in this period. Pilgrims of Beauty is made possible by a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Additional support for the exhibition is provided by Shawmut Design and Construction. CHECKLIST OF THE EXHIBITION William Merritt Chase American, 1849-1916 In Venice, ca. 1877 Oil on panel Bequest of Isaac C. Bates 13.846 William Merritt Chase was one of the earliest painters to work in Venice using the new Impressionist style. In sketches like this, he uses short, loose brushstrokes to study the play of light, color, and reflections around a row of ordinary houses in the quiet Dorsoduro neighborhood, with the dome of the Chiesa dei Gesuati beyond. These same qualities and challenges later lured Renoir, Monet, Sargent, and many others to the city on the lagoons. Chase was evidently proud of this work, despite its modest size. He exhibited it at the Providence Art Club in 1882, where it was purchased by local collector Isaac Bates. -

American Picture Frames of the Arts and Crafts Period

- -~- -- ~ -~~=-- - ----~ - """" PL I. Caprice in Purple and Gold: The Golden Screen, by James McNeill Whistler (1831-1903), 1861, in a frame designed by Whistler. Signed and dated "Whistler. 1861. "at lower left The painting is oil on woodpaneL The frame is carved, incised, and gilded wood with applied cast ornament; opening size, 20¼ by 26¾ inches. The frame in corporates such Oriental motifs as whorls and paulownia leaves. The outer band is a design called Chinese No. 1 in Owen Jones (1809- 1871), Grammar of Ornament (London, 1856), PL LIX. Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. he fascinating history of the American picture profiles and to much simpler frames elegantly hand frame chronicles the evolution of decorative and artis carved and subtly gilded to harmonize with the works tic trends in this country, but it is only in recent years of art within them. Some frames were signed and/ or that American frames have come to be appreciated in dated. their own right by museums, collectors, and dealers.1 James McNeill Whistler was among the first Ameri Until the early 1870's frames were predominantly of can artists to perceive the frames on his works as ex wood with many sections of cast ornament, applied tensions of his paintings. His designs for frames re and gilded. Designs often incorporated naturalistic ele flected not only the aesthetic of the Pre-Raphaelites3 ments which mirrored the celebration of the Ameri but also the assimilation of seventeenth-century Dutch can landscape by painters of the Hudson River school. frames, Oriental ceramics, the interiors of the English As industrialization increased after the Civil War so architect and designer Thomas Jeckyll (1827-1881), did a counter movement which emphasized simplicity and patterns gleaned from Owen Jones's Grammar of of design, hand craftsmanship, and a greater role for Ornament of 1856.4 the decorative arts. -

ON the EDGE of CHANGE Artist-Designed Frallles Frolll Whistler to Marin

PART II: THE INDIVIDUALITY OF FRAME STYLES CHaPTer FIVe ON THE EDGE OF CHANGE Artist-Designed Frallles frolll Whistler to Marin Suzanne Smeaton ON THE EDGE OF CHANGE EVer SIIlCe THe aDVellT OF THe IIlDIVIDUaL PICTUre Frame centuries ago , artists have been concerned with frames not only as surrounds to physically hold their artworks but also as significant components in the presentation of their art. By the mid nineteenth century, framemakers were able to draw on several previous centuries for inspiration in both frame design and fabrication techniques, and artists were participating personally in the design and crafting of frames for their artworks. This relationship among the artist, the artwork, and the frame is interesting for many reasons. Sometimes the artist actually constructed the frame, and at other times he or she designed the frame and someone else constructed it; elements became identified with a particular artist, whether or not he or she created them. Geography influenced designs, and frame styles were sometimes dictated by the subject matter of the paintings. American expatriate James McN eill Whistler (1834- 1903) was one of the earliest innovators in frame design. Whistler was well aware of the designs by the British Pre-Raphaelite artists, who were themselves experimenting with frame design. 1 He created frame designs in the 1860s similar to those designed by his friend and fellow artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The frame on Caprice in Purple and Gold, the Golden Screen (FIGURE 32) has a broad flat panel with incised surface spirals and designs similar to those on the frame on Rossetti's Beata Beatrix. -

Issue of Abo Underrnttelser

i • : ft \ ST —-ir-1 r v*^fr^ ; f >-il —■ •■in I zr% v.> ' >«"v'--. Hake ^Newsletter 3 2 On the cover is a drawing by Bo Lindberg of the Blakes in Abo, Finland, in 1824. Lindberg had this to say about the drawing: In 1974 the oldest surviving Finnish newspaper, Abo Underrnttelser (published in Swedish, formerly the language of the Finnish intelligensia, and still spoken by many Finns), celebrated its 150th anniversary. The editor asked me to make a drawing of Abo in 1824, showing people reading the first copies of the Abo Underrnttelser, and, in the background, the Cathedral, the old town center, and the bridge across the River Aura with the small kiosk on it--from this kiosk the newspaper was sold. None of the buildings except the Gothic Cathedral survived the great fire of 1827. The Abo of the early 19th century was "a most infamous pit, a pestified place, having a poisoned atmosphere, poor pavements and the worst 'esprit public' in the world," wrote Gustaf Mauritz Armfelt about 1800. Since Blake was in the habit of visiting infamous places such as Babylon and Hell, he must have made a spiritual journey to Abo--and, since a spirit is not a cloudy vapour or a nothing, his spirit must have had a solid body, resembling his mortal body. Further, it is well known that Catherine partook in her husband's visions. Therefore I put William Blake and his wife among the readers of the first issue of Abo Underrnttelser. Their clothes are more or less right for 1824. -

Fine Paintings

FINE PAINTINGS Thursday, October 22, 2020 DOYLE.COM FINE PAINTINGS AUCTION Thursday, October 22, 2020 at 10am Eastern EXHIBITION Saturday, October 17, Noon – 5pm Sunday, October 18, Noon – 5pm Monday, October 19, Noon – 5pm Safety protocols will be in place with limited capacity. Please maintain social distance during your visit. LOCATION Doyle Auctioneers & Appraisers 175 East 87th Street New York, NY 10128 212-427-2730 DOYLE.COM Sale Info View Lots and Place Bids Doyle New York 1001 1002 Henri Joseph Harpignies Jules Dupre French, 1819-1916 French, 1811-1889 View to a Watermill Toward Calmer Waters Signed h. harpignies (ll); with the Lorenzo Pellerano Signed Jules Dupre (ll); with various inscribed Collection, Buenos Aires stamp on the reverse numbers and indistinct red wax seal on the reverse Oil on canvas Oil on panel 17 1/2 x 12 inches (44.5 x 30.5 cm) 11 1/4 x 10 5/8 inches (28.5 x 27 cm) $800-1,200 Provenance: Collection of Lorenzo Pellerano, Buenos Aires Sale, Guerrico & Williams, Venta de la Galeria de Cuadros de D. Lorenzo Pellerano, Buenos Aires, Oct. 1933, lot 263 Ambassador Lucio Del Solar, Buenos Aires $2,000-4,000 1003 1004 Frank Dillon Elihu Vedder British, 1823-1909 American, 1836-1923 Arabs at Prayer on the Banks of the Nile, 1898 Landscape by the Sea, 1865 Signed and dated F. Dillon 1898 (lr) Initialed and dated V 1865 (ll) Oil on canvas Oil on canvas 31 1/4 x 53 3/8 inches (79.4 x 135.5 cm) 7 3/4 x 17 1/4 inches (19.6 x 43.8 cm) $1,500-2,500 Provenance: Sale, Sotheby's, London, Sep. -

Willa Cather Collection Finding Aid

Willa Cather Collection Finding Aid Biographical Note Willa Sibert Cather was born in Back Creek Valley, Virginia, on December 7, 1873. In 1883 her family moved to Nebraska, settling in Red Cloud two years later. Cather attended the University of Nebraska and began publishing reviews and stories in local papers. She graduated in 1895 and subsequently took a position at Home Monthly magazine in Pittsburgh, Pa. In 1906 she moved to New York to join the staff of McClure's Magazine, where she worked as managing editor until 1912. With her long-time companion Edith Lewis, she made New York her permanent home. In 1923 Cather was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for One of Ours. She died on April 24, 1947. Her books include: April Twilights (1903), The Troll Garden (1905), Alexander's Bridge (1912), O Pioneers! (1913), The Song of the Lark (1915), My Antonia (1918), Youth and the Bright Medusa (1920), One of Ours (1922), A Lost Lady (1923), The Professor's House (1925), My Mortal Enemy (1926), Death Comes for the Archbishop (1927), Shadows on the Rock (1931), Obscure Destinies (1932), Lucy Gayheart (1935), Not Under Forty (1936), Sapphira and the Slave Girl (1940), and, posthumously, The Old Beauty and Others (1948). Scope Note and Provenance Drew University Library's Willa Cather Collection is a fully cataloged collection of printed and manuscript materials, comprised of works from the collections of Frederick B. Adams, Finn and Barbara Caspersen, Earl and Achsah Brewster, Yehudi Menuhin, Louise Guerber Burroughs, and Frances Holt. Included are books, serial publications, essays, articles and reviews; manuscripts and typescripts; correspondence to, from and about Cather; personal notebooks; photographs and ephemera. -

VIEWS of the GRAND TOUR from the Late 18Th to the 19Th Century PAOLO ANTONACCI - ROMA 2012 - ROMA ANTONACCI PAOLO

VIEWS OF THE GRAND TOUR From the late 18th to the 19th Century PAOLO ANTONACCI - ROMA 2012 - ROMA ANTONACCI PAOLO PAOLO ANTONACCI Via del Babuino 141/A 00187 Roma Tel. +39 06 32651679 [email protected] www. paoloantonacci.com VIEWS OF THE GRAND TOUR From the late 18th to the 19th Century JUNE 2012 Catalogue by: PAOLO ANTONACCI ALVARO MARIGLIANI PAOLO ANTONACCI ROMA PAOLO ANTONACCI ANTICHITÀ S.R.L. Via del Babuino 141/A 00187 Roma Tel. + 39 06 32651679 [email protected] www.paoloantonacci.com Acknowledgements We would like to thank the following people for their help and advice in the preparation of this catalogue: Alberta Campitelli, Pier Andrea De Rosa, Clemente Marigliani, Claudia Nordhoff, Sandro Santolini, Maria Cristina Sordilli © 2012, Paolo Antonacci Catalogue n. 15 Translation from Italian by Miranda MacPhail Photographic references Arte Fotografica, Roma Front Cover Ippolito CAFFI, Venice under the Snow detail, cat. n. 14 Back Cover Fridrich ARNOLD, View of Piazza Colonna in Rome cat. n. 7 PAOLO ANTONACCI Catalogue ANTICHITÀ S.R.L. Via del Babuino 141/A 00187 Roma Tel. + 39 06 32651679 [email protected] www.paoloantonacci.com Acknowledgements We would like to thank the following people for their help and advice in the preparation of this catalogue: Alberta Campitelli, Pier Andrea De Rosa, Clemente Marigliani, Claudia Nordhoff, Sandro Santolini, Maria Cristina Sordilli © 2012, Paolo Antonacci Catalogue n. 15 Translation from Italian by Miranda MacPhail Photographic references Arte Fotografica, Roma Front Cover Ippolito CAFFI, Venice under the Snow detail, cat. n. 14 Back Cover Fridrich ARNOLD, View of Piazza Colonna in Rome cat. -

Founding an American School American an Founding

Founding an American School John Frederick Kensett (Cheshire, CT, 1816–1872 New York City) The Bash-Bish 1855 Oil on canvas Bequest of James A. Suydam, 1865 Kensett’s paintings of the Bash-Bish Falls, located on the border between New York and Massachusetts, are seemingly the noisiest paintings he ever made. We come upon the scene as if stumbling into a sacred place, but there are no faeries or nymphs, just nature itself, presenting a prospect that approaches the miraculous in its con!uence of light and shadow; near and far; rocks, pool, waterfall, forest, and mountain; earth, air, "re (light), and water. Close to the picture plane, the “wide stance” contrapposto [alignment] of the falls closely evokes the human body, intensifying the viewer’s sense that his own gaze, whether looking at a painting or at an actual landscape, is something embodied: to consciously look at something is to take one’s own measure in relation to it. And I never forget that paintings are bodies, too. —Stephen Westfall, NA 1.1 For America: Paintings from the National Academy of Design New Mexico Museum of Art · October 24, 2020 – January 17, 2021 Founding an American School Edward Harrison May (Croydon, England, 1824–1887 Paris, France) Frederic Edwin Church not dated Oil on canvas ANA diploma presentation, May 7, 1849 Frederic Edwin Church (Hartford, CT, 1826–1900 New York City) Scene among the Andes 1854 Oil on canvas Bequest of James A. Suydam, 1865 1.2 For America: Paintings from the National Academy of Design New Mexico Museum of Art · October 24, 2020 – January 17, 2021 Founding an American School Asher B. -

Melville's Prints: David Metcalf's Prints and Tile

Melville's prints: David Metcalf's prints and tile The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Wallace, Robert K. 1999. Melville's prints: David Metcalf's prints and tile. Harvard Library Bulletin 8 (4), Winter 1997: 3-33. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42674978 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA 3 Melville's Prints: David Metcalf s Prints and Tile Robert K. Wallace erman Melville's granddaughter Eleanor Melville Metcalf was a central fig- H ure in the preservation of his books, his manuscripts, and his art collection, as well as in the revival of his literary reputation. In 1942 she donated one hun- dred books from his personal library to the Harvard College Library. Ten years ROBERT K. WALLACE 1s later, she donated nearly three hundred engravings from his personal art collec- Regents' Professor at Northern tion to the Berkshire Athenaeum in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. One of the engrav- Kentucky University. He has published widely on Melville ings now in Pittsfield, Satan Exalted Sat by John Martin, had been a personal and the visual arts. favorite of Eleanor's son David Metcalf; he remembers it in his boyhood bed- room.' Two additional engravings from Herman Melville's collection remain in David Metcalfs possession. -

Madison Council Bulletin Fall 2007

madison council bulletin FALL 2007 At left: Nanzenji in Snow, Masao Ido, 2003, from “On the Cutting Edge: Contemporary Japanese Prints,” an exhibition of 212 fine prints from the College Women’s Association of Japan (CWAJ), made possible through the generous support of Anthony and Beatrice Welters. See page 4. In This Issue The Madison Council Bulletin is a A Word from the Librarian ..........................................3 publication of the James Madison Council of the Library of Congress. On the Cutting Edge: Contemporary Japanese Prints...................4 James H. Billington Librarian of Congress Madison Council Meeting Spring 2007 ...............................8 Jo Ann Jenkins Chief Operating Officer Drawings by Winold Reiss Join Library’s Collection ...................11 Susan K. Siegel Director of Development Interns Find Mother Lode of Materials in Deposits....................13 H.F. “Gerry” Lenfest Chairman Leonard L. Silverstein Newly Discovered Le Page du Pratz Map Acquired by Library..........16 Treasurer Library Acquires First Digital Panoramas of New York City Design: Carla Badaracco Street Corners ....................................................18 Photography: John Harrington pp. 8-10; Nancy Alfaro pp. 13-15 Welcome to New Members Don and Doris Fisher ....................20 Contributors: Katherine Blood, Audrey Fischer, John Hébert, Carol Johnson, Raquel Maya, Shapiros Acquire Szyk Haggadah for Library .........................21 Peggy Pearlstein National Book Festival.............................................22 Front and Back Cover: Samurai House in Autumn, Noboru Yamataka, 2004; Inside Back Cover: A Nebula No. 3, Hideo Hagiwara, 1987 A Word from the Librarian his has been a busy and rewarding summer at the nation’s library. Thanks to the committed involvement T and financial support of the Madison Council the Library will shortly open a state-of-the-art knowledge center in the magnificent public spaces of the Thomas Jefferson Building.