Walker Art Building Murals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PUBLIC SCULPTURE LOCATIONS Introduction to the PHOTOGRAPHY: 17 Daniel Portnoy PUBLIC Public Sculpture Collection Sid Hoeltzell SCULPTURE 18

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 VIRGINIO FERRARI RAFAEL CONSUEGRA UNKNOWN ARTIST DALE CHIHULY THERMAN STATOM WILLIAM DICKEY KING JEAN CLAUDE RIGAUD b. 1937, Verona, Italy b. 1941, Havana, Cuba Bust of José Martí, not dated b. 1941, Tacoma, Washington b. 1953, United States b. 1925, Jacksonville, Florida b. 1945, Haiti Lives and works in Chicago, Illinois Lives and works in Miami, Florida bronze Persian and Horn Chandelier, 2005 Creation Ladder, 1992 Lives and works in East Hampton, New York Lives and works in Miami, Florida Unity, not dated Quito, not dated Collection of the University of Miami glass glass on metal base Up There, ca. 1971 Composition in Circumference, ca. 1981 bronze steel and paint Location: Casa Bacardi Collection of the University of Miami Gift of Carol and Richard S. Fine aluminum steel and paint Collection of the University of Miami Collection of the University of Miami Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alfred Camner Location: Gumenick Lobby, Newman Alumni Center Collection of the Lowe Art Museum, Collection of the Lowe Art Museum, Location: Casa Bacardi Location: Casa Bacardi Location: Gumenick Lobby, Newman Alumni Center University of Miami University of Miami Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Blake King, 2004.20 Gift of Dr. Maurice Rich, 2003.14 Location: Wellness Center Location: Pentland Tower 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 JANE WASHBURN LEONARDO NIERMAN RALPH HURST LEONARDO NIERMAN LEOPOLDO RICHTER LINDA HOWARD JOEL PERLMAN b. United States b. 1932, Mexico City, Mexico b. 1918, Decatur, Indiana b. 1932, Mexico City, Mexico b. 1896, Großauheim, Germany b. 1934, Evanston, Illinois b. -

Understanding the Value of Arts & Culture | the AHRC Cultural Value

Understanding the value of arts & culture The AHRC Cultural Value Project Geoffrey Crossick & Patrycja Kaszynska 2 Understanding the value of arts & culture The AHRC Cultural Value Project Geoffrey Crossick & Patrycja Kaszynska THE AHRC CULTURAL VALUE PROJECT CONTENTS Foreword 3 4. The engaged citizen: civic agency 58 & civic engagement Executive summary 6 Preconditions for political engagement 59 Civic space and civic engagement: three case studies 61 Part 1 Introduction Creative challenge: cultural industries, digging 63 and climate change 1. Rethinking the terms of the cultural 12 Culture, conflict and post-conflict: 66 value debate a double-edged sword? The Cultural Value Project 12 Culture and art: a brief intellectual history 14 5. Communities, Regeneration and Space 71 Cultural policy and the many lives of cultural value 16 Place, identity and public art 71 Beyond dichotomies: the view from 19 Urban regeneration 74 Cultural Value Project awards Creative places, creative quarters 77 Prioritising experience and methodological diversity 21 Community arts 81 Coda: arts, culture and rural communities 83 2. Cross-cutting themes 25 Modes of cultural engagement 25 6. Economy: impact, innovation and ecology 86 Arts and culture in an unequal society 29 The economic benefits of what? 87 Digital transformations 34 Ways of counting 89 Wellbeing and capabilities 37 Agglomeration and attractiveness 91 The innovation economy 92 Part 2 Components of Cultural Value Ecologies of culture 95 3. The reflective individual 42 7. Health, ageing and wellbeing 100 Cultural engagement and the self 43 Therapeutic, clinical and environmental 101 Case study: arts, culture and the criminal 47 interventions justice system Community-based arts and health 104 Cultural engagement and the other 49 Longer-term health benefits and subjective 106 Case study: professional and informal carers 51 wellbeing Culture and international influence 54 Ageing and dementia 108 Two cultures? 110 8. -

Art Museum Digital Impact Evaluation Toolkit

Art Museum Digital Impact Evaluation Toolkit Developed by the Cleveland Museum of Art’s Office of Research & Evaluation in collaboration with Rockman et al thanks to a generous grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. 2018 Content INTRODUCTION ..........................................................2 01 VISITOR CONTEXT .....................................................3 Demographics ............................................................4 Motivations ..............................................................5 Visitation Frequency .......................................................6 02 CONTEXT OF THE DIGITAL EXPERIENCE ...................................7 Prior Digital Engagement ................................................... 8 Timing of Interactive Experience ..........................................9 03 VISITORS’ RELATIONSHIP WITH ART .....................................10 04 ATTITUDES AND IDEAS ABOUT ART MUSEUMS .............................12 Perceptions of the Art Museum ..............................................13 Perceptions of Digital Interactives ............................................14 05 OVERALL EXPERIENCE AND IMPACT ....................................15 06 AREAS FOR FURTHER EXPLORATION .....................................17 ABOUT THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART ...................................19 Introduction The Art Museum Digital Impact Evaluation Toolkit in which the experience was studied. The final (AMDIET) is intended to provide artmuseums and version of data collection instruments -

Fine Arts Policies and Procedures 2017

FINE ARTS POLICIES AND PROCEDURES Executive Summary 1. Introduction 1.1. Mission and Vision Statements 1.1.1. Fine Arts Program Mission 1.1.2. Vision 1.2. Adherence to Ethical Standards 1.3. The Fine Arts Program 1.3.1. Fine Arts Program Within GSA 1.3.2. Responsibilities of the Fine Arts Program 1.3.3. Regional Fine Arts Officers 2. The Collection 2.1. Scope of the Fine Arts Collection 2.2. Description of the Fine Arts Collection 2.3 Asserting Title on New Deal Works 2.4. Accessioning Artworks Into the Fine Arts Collection 2.4.1. Collection Criteria 2.4.2. Art in Architecture Program 2.4.3. Donation of Artwork From Non-Government Sources 2.4.4. Artwork Transferred From Other Federal Agencies 2.4.5. Artwork Accepted Through Building Acquisition 2.4.6. Accessioning Procedure 2.5. Deaccessioning Artworks 2.5.1. Deaccessioning Criteria 2.5.2. Deaccessioning Procedure 3. Use of Artworks 3.1. Public Display 3.1.1. Permanent Installation in GSA-Owned Buildings 3.1.2. Temporary Display in GSA-Owned Buildings 3.1.3. Installation in Leased Properties 3.2. Access 3.2.1. Physical Access 3.2.2. Collection Information 3.3. Loans 3.3.1. Outgoing Loans 3.3.2. Incoming Loans 3.3.3. Loan Procedure 3.3.4. Loans to Tenant Agencies 3.3.5. Insurance 3.4. Relocation of Artworks 3.4.1. Relocation Eligibility 3.4.2. Requesting Relocation 3.4.3. New Location 3.4.4. Funding 1 of 87 3.4.5. -

ANNUAL REPORT Report for the Fiscal Year July 1, 2016–June 30, 2017 ANNUAL REPORT Report for the Fiscal Year July 1, 2016– June 30, 2017

ANNUAL REPORT Report for the fiscal year July 1, 2016–June 30, 2017 ANNUAL REPORT Report for the fiscal year July 1, 2016– June 30, 2017 CONTENTS Director’s Foreword..........................................................3 Milestones ................................................................4 Acquisitions ...............................................................5 Exhibitions ................................................................7 Loans ...................................................................10 Clark Fellows .............................................................11 Scholarly Programs ........................................................12 Publications ..............................................................16 Library ..................................................................17 Education ............................................................... 21 Member Events .......................................................... 22 Public Programs ...........................................................27 Financial Report .......................................................... 37 DIRECTOR’S FOREWORD The Clark Art Institute’s new campus has now been fully open for over a year, and these dynamic spaces fostered widespread growth in fiscal year 2017. In particular, the newly reopened Manton Research Center proved that the Clark’s capacity to nurture its diverse community through exhibitions, gallery talks, films, lectures, and musical performances remains one of its greatest strengths. -

MURALS Call to Artists Downtown Winter Garden Public Art Mural Pilot Project

Up To $7000 Up To $3000 Up To $8000 MURALS Call To Artists Downtown Winter Garden Public Art Mural Pilot Project The city of Winter Garden is initiating a pilot public mural program in the historic downtown district to build community pride, build a stronger community identity and activate some key streets by bringing pedestrian activity to streets such as Main, Boyd, Joiner and Tremaine Streets. Historically, murals were used to advertise and draw interest to a street or store. Downtown Winter Garden has had some murals over the years, but currently does not have any murals remaining. The City has asked the Winter Garden Art Association to assist in the call for artists and selection process. The city invites qualified artists to submit proposals for up to three murals to be placed on/or painted on the walls at three locations in the Downtown District. The City has allocated up to $7,000 for Site #1 and $3,000 for Site #2 to be paid to each mural artist. The fee to be paid for Site #3 is to be determined based on the # of sections chosen by the artist, not to exceed $8000. Each mural shall be interactive and encourage creative thought and activity. If the applicant wishes to create a mural of higher value, the applicant must make a case to justify it and demonstrate the ability to secure a portion of the additional funds. The installed mural will become the property of the city of Winter Garden. This initiative will be called #wheregoodthingsgrow and/or #acharmingcitywithajuicypast. -

JONATHAN MUNDEN 20503 W 200Th St, Spring Hill, KS 66083 (816) 517-2051 [email protected] @MUNDEN1

JONATHAN MUNDEN 20503 W 200th St, Spring Hill, KS 66083 (816) 517-2051 [email protected] www.MundensArt.com @MUNDEN1 Objective Artist with nearly ten years of related work experience, as well as a portfolio of varied exhibitions and murals that can be found locally and nationwide. Munden has risen to become a leading name in the local KC art community and has recently begun to expand his horizons to out-of-state mural festivals. He has a passion for creating and sharing his art, and flourishes seeing the effect his art has on the surrounding communities. Munden got his start in landscape and spacescape painting through performance art at festivals and art fairs. That experience lead him to create cityscape skyline pieces, as well as some graffiti style works. For the past few years, Munden's focus has remained on large portrait realism and the study of facial forms, expressions, and textures. Relevant Professional Experience Artist (Freelance) • Design, develop, and deliver custom, commissioned art pieces to clients according to their specifications. This includes creating digital or hand-drawn sketches of the proposed work, drawing up a contract, establishing a timeline, and executing the art piece as agreed upon to the client’s satisfaction. • Design and create art pieces to fit into theme-specific exhibitions to be shown in prominent galleries throughout the Crossroads Art District. Exhibitions have previously consisted of themes such as the Mad Hatter, High Fashion Portraits, Expression Portraits, Halloween, and KC Skylines. • Collaborate with other artists with regards to collective murals and art pieces. Examples include creating a custom, collaborative, outdoor art-piece for a client on the Plaza, as well as coordinating the division and allocation of a wall for the Spray See Mo Mural Festival last summer after it had been double-booked. -

Crystal Reports

Unknown American View of Hudson from the West, ca. 1800–1815 Watercolor and pen and black ink on cream wove paper 24.5 x 34.6 cm. (9 5/8 x 13 5/8 in.) Princeton University Art Museum. Gift of Edward Duff Balken, Class of 1897 (x1958-44) Unknown American Figures in a Garden, ca. 1830 Pen and black ink, watercolor and gouache on beige wove paper 47.3 x 60.3 cm. (18 5/8 x 23 3/4 in.) frame: 51 × 64.6 × 3.5 cm (20 1/16 × 25 7/16 × 1 3/8 in.) Princeton University Art Museum. Gift of Edward Duff Balken, Class of 1897 (x1958-45) Unknown American The Milkmaid, ca. 1840 – 1850 Watercolor on wove paper 27.9 x 22.9 cm (11 x 9 in.) Princeton University Art Museum. Gift of Edward Duff Balken, Class of 1897 (x1958-49) John James Audubon, American, 1785–1851 Yellow-throated Vireo, 1827 Watercolor over graphite on cream wove paper mat: 48.7 × 36.2 cm (19 3/16 × 14 1/4 in.) Graphic Arts Collection, Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library. Gift of John S. Williams, Class of 1924. Milton Avery, American, 1893–1965 Harbor View with Shipwrecked Hull, 1927 Gouache on black wove paper 45.7 x 30.2 cm. (18 x 11 7/8 in.) Princeton University Art Museum. Bequest of Edward T. Cone, Class of 1939, Professor of Music 1946-1985 (2005-102) Robert Frederick Blum, American, 1857–1903 Chinese street scene, after 1890 Watercolor and gouache over graphite on cream wove paper 22.8 x 15.3 cm. -

Representations of the Female Nude by American

© COPYRIGHT by Amanda Summerlin 2017 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BARING THEMSELVES: REPRESENTATIONS OF THE FEMALE NUDE BY AMERICAN WOMEN ARTISTS, 1880-1930 BY Amanda Summerlin ABSTRACT In the late nineteenth century, increasing numbers of women artists began pursuing careers in the fine arts in the United States. However, restricted access to institutions and existing tracks of professional development often left them unable to acquire the skills and experience necessary to be fully competitive in the art world. Gendered expectations of social behavior further restricted the subjects they could portray. Existing scholarship has not adequately addressed how women artists navigated the growing importance of the female nude as subject matter throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. I will show how some women artists, working before 1900, used traditional representations of the figure to demonstrate their skill and assert their professional statuses. I will then highlight how artists Anne Brigman’s and Marguerite Zorach’s used modernist portrayals the female nude in nature to affirm their professional identities and express their individual conceptions of the modern woman. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I could not have completed this body of work without the guidance, support and expertise of many individuals and organizations. First, I would like to thank the art historians whose enlightening scholarship sparked my interest in this topic and provided an indispensable foundation of knowledge upon which to begin my investigation. I am indebted to Kirsten Swinth's research on the professionalization of American women artists around the turn of the century and to Roberta K. Tarbell and Cynthia Fowler for sharing important biographical information and ideas about the art of Marguerite Zorach. -

An Artist of the American Renaissance : the Letters of Kenyon Cox, 1883-1919 PDF

An Artist of the American Renaissance : The Letters of Kenyon Cox, 1883-1919 PDF Author: H. Wayne Morgan Pages: 197 pages ISBN: 9780873385176 Kenyon Cox was born in Warren, Ohio, in 1856 to a nationally prominent family. He studied as an adolescent at the McMicken Art School in Cincinnati and later at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia. From 1877 to 1882, he was enrolled at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris, and then in 1883 he moved to New York city, where he earned his living as an illustrator for magazines and books and showed easel works in exhibitions. He eventually became a leading painter in the classical style-particularly of murals in state capitols, courthouses, and other major buildings-and one of the most important traditionalist art critics in the United States.An Artist of the American Renaissance is a collection of Cox's private correspondence from his years in New York City and the companion work to editor H. Wayne Morgan's An American Art Student in Paris: The Letters of Kenyon Cox, 1877-1882 (Kent State University Press, 1986). These frank, engaging, and sometimes naive and whimsical letters show Cox's personal development as his career progressed. They offer valuable comments on the inner workings of the American art scene and describe how the artists around Cox lived and earned incomes. Travel, courtship of the student who became his wife, teaching, politics of art associations, the process of painting murals, the controversy surrounding the depiction of the nude, promotion of the new American art of his day, and his support of a modified classical ideal against the modernism that triumphed after the 1913 Armory Show are among the subjects he touched upon.Cox's letters are little known and have never before been published. -

Southeastern Reciprocal Membership Program

SOUTHEASTERN RECIPROCAL MEMBERSHIP PROGRAM Upon presentation of your membership card you will receive: Free admission at all times during museum hours. The same discount in the gift shop and café as those offered to members of that museum. The same discount on purchases made on the premises for concert and lecture tickets, as those offered to members of that museum. Reciprocal privileges do not include receiving mailings from any of the participating museums except for the museum with which the member is affiliated. Note: List subject to change without notice. Museums may temporarily suspend reciprocal program during special exhibitions. Some museums do not accept SERM from other local museums. Call before you go. ALABAMA Augusta Museum of History – Augusta Greensboro Birmingham Museum of Art -- Birmingham Bartow History Museum – Cartersville Greenville Museum of Art – Greenville Carnegie Visual Arts Center -- Decatur Columbus Museum – Columbus Hickory Museum of Art -- Hickory Huntsville Museum of Art – Huntsville Georgia Museum of Art – Athens Mint Museum, Randolph -- Charlotte Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art at Auburn -- Marietta Museum of History – Marietta Mint Museum Uptown – Charlotte Auburn Morris Museum of Art – Augusta Waterworks Visual Art Center – Salisbury Mobile Museum of Art – Mobile Museum of Arts & Sciences – Macon Weatherspoon Art Museum – Greensboro Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts – Montgomery Museum of Design Atlanta – Atlanta Reynolda House Museum of American Art – Winston Wiregrass Museum of Art – Dothan -

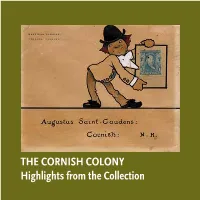

The Cornish Colony Highlights from the Collection the Cornish Colony Highlights from the Collection

THE CORNISH COLONY Highlights from the Collection THE CORNISH COLONY Highlights from the Collection The Cornish Colony, located in the area of Cornish, New The Cornish Colony did not arise all of apiece. No one sat down at Hampshire, is many things. It is the name of a group of artists, a table and drew up plans for it. The Colony was organic in nature, writers, garden designers, politicians, musicians and performers the individual members just happened to share a certain mind- who gathered along the Connecticut River in the southwest set about American culture and life. The lifestyle that developed corner of New Hampshire to live and work near the great from about 1883 until somewhere between the two World Wars, American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. The Colony is also changed as the membership in the group changed, but retained a place – it is the houses and landscapes designed in a specific an overriding aura of cohesiveness that only broke down when the Italianate style by architect Charles Platt and others. It is also an country’s wrenching experience of the Great Depression and the ideal: the Cornish Colony developed as a kind of classical utopia, two World Wars altered American life for ever. at least of the mind, which sought to preserve the tradition of the —Henry Duffy, PhD, Curator Academic dream in the New World. THE COLLECTION Little is known about the art collection formed by Augustus Time has not been kind to the collection at Aspet. Studio fires Saint-Gaudens during his lifetime. From inventory lists and in 1904 and 1944 destroyed the contents of the Paris and New correspondence we know that he had a painting by his wife’s York houses in storage.