NRDC: Home Idle Load - Devices Wasting Huge Amounts of Electricity When Not in Active Use (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of Energy Efficiency Standards on Standby Power in Consumer Electronics Design

THE IMPACT OF ENERGY EFFICIENCY STANDARDS ON STANDBY POWER IN CONSUMER ELECTRONICS DESIGN A Lattice Semiconductor White Paper May 2010 Lattice Semiconductor 5555 Northeast Moore Ct. Hillsboro, Oregon 97124 USA Telephone: (503) 268-8000 www.latticesemi.com 1 The Impact of Energy Efficiency Standards on Standby Power in Consumer Electronics Design A Lattice Semiconductor White Paper Regulatory Measures to Reduce Standby Power Squeezing every last microwatt from a system is a common objective for engineers who are designing battery operated equipment. And as more strict government regulations regarding power consumption appear, even traditional home and office appliances like LCD TVs, set top boxes (STBs) and multi- function printers (MFPs) are being scrutinized for ways to save power. To help ensure products are in compliance with the latest EnergyStar and European Commission Code of Conduct regulations, designers are seeking innovative ways to provide low-power modes of operation in a variety of product lines. This white paper examines design methods and practical advice for saving power using programmable logic devices (PLDs). The 1-Watt Plan is an energy saving proposal by the International Energy Agency (www.iea.org ) to reduce standby power use in all appliances to just one watt. Standby power, also called vampire or phantom power, refers to the electricity consumed by many appliances when they are switched off or in standby mode. The typical power loss per appliance is low (from 1 to 25 W), but when multiplied by the billions of appliances in residential and commercial use, standby losses represent a significant fraction of total world electricity use. -

GMX Standby Power Supply

GMX Standby Power Supply Technical Manual GMX-915 Models Effective: May, 2007 Alpha Technologies ® PowerAlpha Technologies GMX Standby Power Supply 017-932-B0-002, Rev B Effective Date: May, 2007 Copyright© 2007 Alpha Technologies, Inc. member of The GroupTM NOTE: Photographs contained in this manual are for illustrative purposes only. These photographs may not match your installation. NOTE: Operator is cautioned to review the drawings and illustrations contained in this manual before proceeding. If there are questions regarding the safe operation of this powering system, please contact Alpha Technologies or your nearest Alpha representative. NOTE: Alpha shall not be held liable for any damage or injury involving its enclosures, power supplies, generators, batteries, or other hardware if used or operated in any manner or subject to any condition not consistent with its intended purpose, or is installed or operated in an unapproved manner, or improperly maintained. Notice of FCC Compliance Per FCC 47 CFR 15.21: Changes or modifications not expressly approved by the party responsible for compliance could void the user’s authority to operate the equipment. Per FCC 47 CFR 15.105: This equipment has been tested and found to comply with the limits for a Class A digital device, pursuant to part 15 of the FCC Rules. These limits are designed to provide reasonable protection against harmful interference when the equipment is operated in a commercial environment. This equipment generates, uses, and can radiate radio frequency energy and, if not installed and used in accordance with the instruction manual, may cause harmful interference to radio communications. Operation of this equipment in a residential area is likely to cause harmful interference in which case the user will be required to correct the interference at their own expense. -

Guidelines on Energy Conserving Design of Buildings — 2020 Edition

GUIDELINES ON ENERGY CONSERVING DESIGN OF BUILDINGS — 2020 EDITION Section I. Purpose 1.1 To encourage and promote the energy conserving design of buildings and their services to reduce the use of energy with due regard to the cost effectiveness, building function, and comfort, health, safety, and productivity of the occupants. 1.2 To prescribe guidelines and minimum requirements for the energy conserving design of new buildings and major renovation of existing buildings that fall and are covered under these guidelines and provide methods for determining compliance with the same to make the buildings always energy-efficient. Section Il. Definition of Terms 2. As used in these Guidelines, the following shall mean: Air— refers to any of the following: Ambient Air — air surrounding a building; the source of outdoor air brought into a building. Exhaust Air — air removed from a space and discharged to outside the building by means of mechanical or natural ventilation. Indoor Air— air in an enclosed occupiable space. Outdoor Air— ambient air that enters a building through a ventilation system, through intentional openings for natural ventilation, or by infiltration. Return Air— air removed from a space to be recirculated, or exhaust air. Supply Air — air delivered by mechanical or natural ventilation to a space and composed of any combination of outdoor air, recirculated air, or transfer air. Ventilation Air — supply air that is outdoor air plus any recirculated air that has been treated for the purpose of maintaining acceptable Indoor Air Quality. Air Conditioning — the process of treating air so as to control simultaneously its temperature, humidity, cleanliness, and distribution to meet the requirements of conditioned space. -

Final Report

Final Report Team 22 - SHARC Sustainable Housing And Responsible Construction Andrew Blunt, Robert LaPlaca, Oscar Lopez, and Julie VanDeRiet Engineering 339/340 Senior Design Project Calvin College May 10, 2018 © 2018, Calvin College and Andrew Blunt, Robert LaPlaca, Oscar Lopez, and Julie VanDeRiet 1 Executive Summary This document outlines the work that Team 22 of Calvin College’s engineering senior design project achieved over the academic year, as well as the goals they achieved. The accomplished work contains research and feasibility analysis for design decisions regarding the design of the a sustainable home. The client family desires a sustainable home near Calvin College. Team 22’s goal was to provide a solution to their problem by designing a home to comply with Passive House Institute US’s certification. This task requires a variety of engineering disciplines with specific objectives that require a parallel design process. This document outlines the research and work that Team 22 has achieved. Table of Contents 1 Executive Summary 2 Introduction 1 2.1 Project Introduction 1 2.1.1 Location 1 2.1.2 Client 1 2.2 Passive House US Requirements 1 2.3 The Team 3 2.3.1 Andrew Blunt 3 2.3.2 Robert LaPlaca 3 2.3.3 Oscar Lopez 4 2.3.4 Julie VanDeRiet 4 2.4 Senior Design Course 4 3 Results 5 3.1 Thermal Results 5 3.2 Home Design 5 3.3 Energy Performance 6 4 Project Management 7 4.1 Team Organization 7 4.2 Schedule 7 4.2.1 First Semester 7 4.2.2 Second Semester 8 4.2.3 Project Management Visualization 8 5 Design Process 9 5.1 Ethical Design -

Assessing Players, Products, and Perceptions of Home Energy Management ET Project Number: ET15PGE8851

PG&E’s Emerging Technologies Program ET15PGE8851 PG&E’s Emerging Technologies Program Assessing Players, Products, and Perceptions of Home Energy Management ET Project Number: ET15PGE8851 Project Manager(s): Kari Binley and Oriana Tiell Pacific Gas and Electric Company Prepared By: SEE Change Institute Rebecca Ford Beth Karlin Angela Sanguinetti Anna Nersesyan Marco Pritoni Issued: November 19, 2016 Cite as: Ford, R., Karlin, B., Sanguinetti, A., Nersesyan, A., & Pritoni, M. (2016). Assessing Players, Products, and Perceptions of Home Energy Management. San Francisco, CA: Pacific Gas and Electric. © Copyright, 2016, Pacific Gas and Electric Company. All rights reserved. PG&E’s Emerging Technologies Program ET15PGE8851 Acknowledgements Pacific Gas and Electric Company’s Emerging Technologies Program is responsible for this project. It was developed as part of Pacific Gas and Electric Company’s Emerging Technology program under internal project numbers ET15PGE8851. SEE Change Institute conducted this technology evaluation for Pacific Gas and Electric Company with overall guidance and management from Jeff Beresini, Kari Binely and Oriana Tiell. For more information on this project, contact Pacific Gas and Electric Company at [email protected]. Special Thanks This project was truly a team effort and the authors would like to thank all those who contributed to making it a reality. First, we’d like to acknowledge Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E) for funding this research. Particular thanks go to Susan Norris for having the vision and foresight to make this project a reality and to Oriana Tiell, Kari Binley, and Jeff Beresini for continued support and feedback throughout the project. Several partners also collaborated with our team on the various research streams and deserve acknowledgement. -

'Fan-Assisted Combustion' AUD1A060A9361A

AUD1A060-SPEC-2A TAG: _________________________________ Specification Upflow / Horizontal Gas Furnace"Fan-Assisted 5/8" Combustion" 14-1/2" 13-1/4" AUD1A060A9361A 5/8" 28-3/8" 19-5/8" 5/8" 1/2" 4" DIAMETER FLUE CONNECT 7/8" DIA. HOLES ELECTRICAL 9-5/8" CONNECTION 4-1/16" 1/2" 3/4" 2-1/16" 7/8" DIA. K.O. 3-15/16" ELECTRICAL CONNECTION 8-1/4" (ALTERNATE) 13" 40" 3-3/4" 1-1/2" DIA. 3/4" K.O. GAS CONNECTION 2-1/16" (ALTERNATE) 28-1/4" 28-1/4" 3/4" 22-1/2" 23-1/2" 5-5/16" 3-13/16" 1-1/2" DIA. HOLE 3/8" GAS CONNECTION 2-1/8" FURNACE AIRFLOW (CFM) VS. EXTERNAL STATIC PRESSURE (IN. W.C.) MODEL SPEED TAP 0.10 0.20 0.30 0.40 0.50 0.60 0.70 0.80 0.90 AUD1A060A9361A 4 - HIGH - Black 1426 1389 1345 1298 1236 1171 1099 1020 934 3 - MED.-HIGH - Blue 1243 1225 1197 1160 1113 1057 991 916 831 2 - MED.-LOW - Yellow 1042 1039 1027 1005 973 931 879 817 745 1 - LOW - Red 900 903 895 877 848 809 760 700 629 CFM VS. TEMPERATURE RISE MODEL CFM (CUBIC FEET PER MINUTE) 800 900 1000 1100 1200 1300 1400 AUD1A060A9361A 56 49 44 40 37 34 32 © 2009 American Standard Heating & Air Conditioning General Data 1 TYPE Upflow / Horizontal VENT COLLAR — Size (in.) 4 Round RATINGS 2 HEAT EXCHANGER Input BTUH 60,000 Type-Fired Alum. Steel Capacity BTUH (ICS) 3 47,000 -Unfired AFUE 80.0 Gauge (Fired) 20 Temp. -

Download a Transcript of the Interview with Doug King

Episode 63 Smart Energy and Data The show notes: www.houseplanninghelp.com/63 Intro: Data is what we're talking about today. When I go to various different talks they will often reflect on data that has been collected, whether it's from moisture sensors or CO2 sensors so I did wonder whether it's something that I should be doing on my project, making sure that there is something useful coming out of it in terms of data. That probably means planning upfront so I just wanted to find out all about that. Recently I saw a talk on smart energy so I thought we'd tie this all together and see how we go with it. Doug King has a lot of experience in construction, particularly high performance buildings - which is what we like - and he's someone that I've been wanting to talk to for a while. I started by asking him for a little bit of background on his work. Doug: I started out as a physicist. I fell into the profession of building services engineering, out of curiosity, and then I spent the last 20 years thinking about how building services systems work together with building fabric, with the technology to control them and finally how human beings relate to all of that as a system in order to try and understand the key issues about optimisation, how to get these things working together properly rather than the building services systems fighting against the building fabric and the users not understanding what the hell is going on. -

PWP Guide to Portable Generators (PDF)

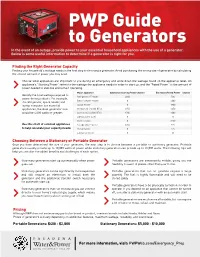

Finding the Right Generator Capacity Finding your household's wattage needs is the first step to choosing a generator. Avoid purchasing the wrong size of generator by calculating the correct amount of power you may need. Choose what appliances are important to you during an emergency and write down the wattage found on the appliance label. An appliance's "Starting Power" refers to the wattage the appliance needs in order to start up, and the "Rated Power" is the amount of > power needed to stabilize and remain operating. Major Appliance Additional Starting Power (watts) Estimated Rated Power (watts) Identify the total wattage required to Ref rige rato r/Freeze r 2000 700 power those products. For example, Electric Water Heater 0 4000 if a refrigerator, space heater, and laptop computer are essential Space Heater 0 1800 > appliances, the ideal generator size Window AC [12,000 BTU) 3950 3250 would be 4,000 watts or greater. Central AC [40,000 BTU) 6700 6000 Lightbulb [75 watt) 0 75 Electric Stove 0 2100 Use this chart of common appliances Garage Door Opener 2350 875 to help calculate your capacity needs: PC Computer 0 125 Laptop Computer 0 25 Choosing Between a Stationary or Portable Generator Once you have determined the size of your generator, the next step is to choose between a portable or stationary generator. Portable generators usually provide up to 10,000 watts of power while stationary generators can provide up to 20,000 watts. The following tips will help you consider the added benefits and challenges of each option. -

Indoor Air Quality (IAQ): Combustion By-Products

Number 65c June 2018 Indoor Air Quality: Combustion By-products What are combustion by-products? monoxide exposure can cause loss of Combustion (burning) by-products are gases consciousness and death. and small particles. They are created by incompletely burned fuels such as oil, gas, Nitrogen dioxide (NO2) can irritate your kerosene, wood, coal and propane. eyes, nose, throat and lungs. You may have shortness of breath. If you have a respiratory The type and amount of combustion by- illness, you may be at higher risk of product produced depends on the type of fuel experiencing health effects from nitrogen and the combustion appliance. How well the dioxide exposure. appliance is designed, built, installed and maintained affects the by-products it creates. Particulate matter (PM) forms when Some appliances receive certification materials burn. Tiny airborne particles can depending on how clean burning they are. The irritate your eyes, nose and throat. They can Canadian Standards Association (CSA) and also lodge in the lungs, causing irritation or the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) damage to lung tissue. Inflammation due to certify wood stoves and other appliances. particulate matter exposure may cause heart problems. Some combustion particles may Examples of combustion by-products include: contain cancer-causing substances. particulate matter, carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, carbon dioxide, sulphur dioxide, Carbon dioxide (CO2) occurs naturally in the water vapor and hydrocarbons. air. Human health effects such as headaches, dizziness and fatigue can occur at high levels Where do combustion by-products come but rarely occur in homes. Carbon dioxide from? levels are sometimes measured to find out if enough fresh air gets into a room or building. -

The Affordable Heat-Circulating Fireplace Offering Style, Value and Performance. After a Hard Day in a Cold World…

F I R E P L A C E S Y S T E M S The affordable heat-circulating fireplace offering style, value and performance. After a Hard Day in a Cold World… The NEW-AIRE FIREPLACE SYSTEM utilizes the basic principles of thermodynamics designed into any new high-efficient forced air furnace (radiant, conductive and convective heat transfer). By forcing air movement through a series of baffles in a specifically designed heat exchanger surrounding a steel firebox, ratings in excess of 200,000 BTU can be achieved in a full-fired condition. With 1050 cubic feet of air per minute at central HVAC static pressures, the NEW-AIRE fireplace easily matches the heat output of any high-efficiency furnace on the market today. Your home is the heart of your family’s life. A warm hearth is the gathering place that defines the spirit of the home. The NEW-AIRE fireplace, clad in brass and glass, provides both the traditional and functional elements needed in today’s life. Unlike stoves and inserts, the NEW-AIRE can be independently ducted to provide whole-house heating beyond the walls of the room in which it is installed. Certified to the International Mechanical Code, when ducted to induce heat into the central heating system, the NEW-AIRE SYSTEM efficiently provides the required heat for 4000 plus square foot homes. The NEW-AI Airtight /Airwash Door Control: heat loss, wood consumption, and smoke in the winter — air infiltration and ash smell in the summer. Makes any fireplace more efficient by controlling the “burn rate”. -

20152016 Basic Appliance Repair Syllabus Fred's Appliance Academy

20152016 Basic Appliance Repair Syllabus Fred’s Appliance Academy Contact Information: Instructor: Fred Butcher Email: [email protected] Instructor: Alex Hallmark Email: [email protected] Admin: Jamie Lovejoy Email: [email protected] Phone: 4402497246 Description: At Fred's Appliance Academy, students will receive handson classroom instruction from an instructor with over 30 years experience in the appliance repair industry. The class will start with basic electrical circuitry and schematic training, followed by laundry, kitchen, and refrigeration. A variety of makes and models will be introduced to the students allowing for a complete education on appliance repair. The course wraps up with the ioAST certification exam and the NASTeC certification exam. Course Points: ● Electrical theory ● Handson experience ● Internet skills ● Schematic reading ● Proper tools ● Soft Computer Skills ● Brazing/soldering ● Troubleshooting ● Parts lookup ● Washers ● Dryers ● Refrigerators ● Dishwashers ● Microwaves ● EPA Certification ● Range hoods ● Highend product intro ● NASTeC Certification ● ioAST Certification Requirements: To successfully complete this course, it is advised that you not only pay attention in class, but take notes, and participate in the handson training sessions. While this course is designed to give you a foundation for a successful career in appliance repair, it is up to you to take the technical information learned and apply it. In order to participate in class you must have an email address that you can remotely access. Registration is open to any adult over the age of 18; students are required to be able to lift fifty (50) pounds. Students must have Type 1 608 EPA license. -

American Standard Humidifiers – Our Dealers Will Put You in Designed to Complete Your Matched System and Your Comfort

Achieve a better balance and a better level of comfort. Whole-Home Humidifiers Say good-bye to dry. Bone dry Arid outside Comfort for your body and mind. How an American Standard humidifier outside During the winter or in arid climates, the air in your home can leave benefits your family: you feeling parched. You may experience dry skin, brittle hair, • Provides potential energy savings during heating by cracked lips, itchy eyes and irritated nasal passages. Your furniture, making the air feel warmer, so you’re more comfortable setting your thermostat lower. woodwork and musical instruments may also suffer as the dry air • Reduces static electricity so you won’t have any leaches their essential moisture. By balancing the moisture level in shocking experiences. your home, an American Standard humidifier improves your comfort • Prevents skin, hair and nasal passages from drying out. and protects your belongings. And when the mercury dips, a • Protects your furniture, woodwork, artwork, books, Inside it’s just the way you like it. Thanks to American Standard Heating & Air Conditioning. humidifier can also help you save on your heating costs. With the plants and other valuables. right amount of moisture in the air, you’ll feel warmer and be able to keep your thermostat at a lower, more efficient setting. • Lessens shrinkage of woodwork around doors and windows. American Standard Humidifiers – Our dealers will put you in Designed to complete your matched system and your comfort. More than 100 years your comfort zone. of feeling right at home. When it comes to your home comfort system, you may find yourself thinking peace of mind.