Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marxman Mary Jane Girls Mary Mary Carolyne Mas

Key - $ = US Number One (1959-date), ✮ UK Million Seller, ➜ Still in Top 75 at this time. A line in red 12 Dec 98 Take Me There (Blackstreet & Mya featuring Mase & Blinky Blink) 7 9 indicates a Number 1, a line in blue indicate a Top 10 hit. 10 Jul 99 Get Ready 32 4 20 Nov 04 Welcome Back/Breathe Stretch Shake 29 2 MARXMAN Total Hits : 8 Total Weeks : 45 Anglo-Irish male rap/vocal/DJ group - Stephen Brown, Hollis Byrne, Oisin Lunny and DJ K One 06 Mar 93 All About Eve 28 4 MASH American male session vocal group - John Bahler, Tom Bahler, Ian Freebairn-Smith and Ron Hicklin 01 May 93 Ship Ahoy 64 1 10 May 80 Theme From M*A*S*H (Suicide Is Painless) 1 12 Total Hits : 2 Total Weeks : 5 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 12 MARY JANE GIRLS American female vocal group, protégées of Rick James, made up of Cheryl Ann Bailey, Candice Ghant, MASH! Joanne McDuffie, Yvette Marine & Kimberley Wuletich although McDuffie was the only singer who Anglo-American male/female vocal group appeared on the records 21 May 94 U Don't Have To Say U Love Me 37 2 21 May 83 Candy Man 60 4 04 Feb 95 Let's Spend The Night Together 66 1 25 Jun 83 All Night Long 13 9 Total Hits : 2 Total Weeks : 3 08 Oct 83 Boys 74 1 18 Feb 95 All Night Long (Remix) 51 1 MASON Dutch male DJ/producer Iason Chronis, born 17/1/80 Total Hits : 4 Total Weeks : 15 27 Jan 07 Perfect (Exceeder) (Mason vs Princess Superstar) 3 16 MARY MARY Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 16 American female vocal duo - sisters Erica (born 29/4/72) & Trecina (born 1/5/74) Atkins-Campbell 10 Jun 00 Shackles (Praise You) -

27 August 2018 See P91—137 — See Children’S Programme Gifford Baillie Thanks to All Our Sponsors and Supporters

FREEDOM. 11 — 27 August 2018 Baillie Gifford Programme Children’s — See p91—137 Thanks to all our Sponsors and Supporters Funders Benefactors James & Morag Anderson Jane Attias Geoff & Mary Ball The BEST Trust Binks Trust Lel & Robin Blair Sir Ewan & Lady Brown Lead Sponsor Major Supporter Richard & Catherine Burns Gavin & Kate Gemmell Murray & Carol Grigor Eimear Keenan Richard & Sara Kimberlin Archie McBroom Aitken Professor Alexander & Dr Elizabeth McCall Smith Anne McFarlane Investment managers Ian Rankin & Miranda Harvey Lady Susan Rice Lord Ross Fiona & Ian Russell Major Sponsors The Thomas Family Claire & Mark Urquhart William Zachs & Martin Adam And all those who wish to remain anonymous SINCE Scottish Mortgage Investment Folio Patrons 909 1 Trust PLC Jane & Bernard Nelson Brenda Rennie And all those who wish to remain anonymous Trusts The AEB Charitable Trust Barcapel Foundation Binks Trust The Booker Prize Foundation Sponsors The Castansa Trust John S Cohen Foundation The Crerar Hotels Trust Cruden Foundation The Educational Institute of Scotland The Ettrick Charitable Trust The Hugh Fraser Foundation The Jasmine Macquaker Charitable Fund Margaret Murdoch Charitable Trust New Park Educational Trust Russell Trust The Ryvoan Trust The Turtleton Charitable Trust With thanks The Edinburgh International Book Festival is sited in Charlotte Square Gardens by the kind permission of the Charlotte Square Proprietors. Media Sponsors We would like to thank the publishers who help to make the Festival possible, Essential Edinburgh for their help with our George Street venues, the Friends and Patrons of the Edinburgh International Book Festival and all the Supporters other individuals who have donated to the Book Festival this year. -

United States Bankruptcy Court for the District of Delaware

Case 17-10805-LSS Doc 410 Filed 11/02/17 Page 1 of 285 IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE In re: Chapter 11 UNILIFE CORPORATION, et al., 1 Case No. 17-10805 (LSS) Debtors. (Jointly Administered) AFFIDAVIT OF SERVICE STATE OF CALIFORNIA } } ss.: COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES } DARLEEN SAHAGUN, being duly sworn, deposes and says: 1. I am employed by Rust Consulting/Omni Bankruptcy, located at 5955 DeSoto Avenue, Suite 100, Woodland Hills, CA 91367. I am over the age of eighteen years and am not a party to the above-captioned action. 2. On October 30, 2017, I caused to be served the: a. Plan Solicitation Cover Letter, (“Cover Letter”), b. Official Committee of Unsecured Creditors Letter, (“Committee Letter”), c. Ballot for Holders of Claims in Class 3, (“Class 3 Ballot”), d. Notice of (A) Interim Approval of the Disclosure Statement and (B) Combined Hearing to Consider Final Approval of the Disclosure Statement and Confirmation of the Plan and the Objection Deadline Related Thereto, (the “Notice”), e. CD ROM Containing: Debtors’ First Amended Combined Disclosure Statement and Chapter 11 Plan of Liquidation [Docket No. 394], (the “Plan”), f. CD ROM Containing: Order (I) Approving the Disclosure Statement on an Interim Basis; (II) Scheduling a Combined Hearing on Final Approval of the Disclosure Statement and Plan Confirmation and Deadlines Related Thereto; (III) Approving the Solicitation, Notice and Tabulation Procedures and the Forms Related Thereto; and (IV) Granting Related Relief [Docket No. 400], (the “Order”), g. Pre-Addressed Postage-Paid Return Envelope, (“Envelope”). (2a through 2g collectively referred to as the “Solicitation Package”) d. -

Samstag, 18.04.2015 Interpret Titel Format Label Info

Record Store Day - Samstag, 18.04.2015 Interpret Titel Format Label Info !!!'s first release since 2013's THR!!!ER presents the band at their dance 12 inch core with two new house influenced !!! (Chk Chk Chk) All U Writers / Gonna Guetta Stomp 12" WARP tracks. The record approaches sounds of the band's past remixers like Maurice Fulton and Anthony Naples, riding the dance floor as only a 500 Stück - rotes Vinyl, ausführliche Linernotes, 2 exklusive (International) Noise Conspiracy, The Live At Oslo Jazz Festival 2002 Vinyl LP Eliterecords non-Album-Tracks 16 HORSEPOWER FOLKLORE LP VOLKOREN 16 HORSEPOWER OLDEN LP VOLKOREN A: Mary Mary (Seahawks Deep Love For All Mankind Remix) / B: Run Run Run (Wrong Island's Cosmic Plughole Remix) w/CD 2 Bears, The Bears In Space 12" Southern Fried (7 Remixe) 24 GONE THE SPIN LP CULTURE CLASH RECORDS 4 Promille Vinyl 7" Single Sunny Bastards 7" Single / Etched B-Side 4 Promille Vinyl 7" Single Sunny Bastards 7" Single / Etched B-Side / Colored Vinyl 999 BIGGEST PRIZE IN SPORT / BIGGEST TOUR IN SPORT LP LETTHEMEATVINYL A Coral Room I.o.T. Vinyl LP INFRACom! RSD 2015 AD LIBS, THE YOU'LL ALWAYS BE IN MY STYLE / THE BOY FROM NYC 7" CHARLY AGAINST ME! OSAMA BIN LADEN AS THE CRUCIFIED CHRIST 7" TOTAL TREBLE AGATHOCLES MINCER (RSD 2015) LP POWER IT UP Limited edition White colored version in 100 copies worldwide. * Setting a new standard for swedish melodic black metal. SOUND POLLUTION / BLACK Ages Malefic Miasma LP * With ex-member from Dissection, Satyricon (live). -

Inverness Burgh Directory 1941-1942

INVERNESS BURGH DIRECTORY 1941-1942 Containing Street and Alphabetical Directory : also Official Information Price - - 5/- ROBT. CARRUTHERS & SONS INVERNESS THE PREMIER INVERNESS LAUNDRY CO., LTD: MONTAGUE ROW :: INVERNESS HIGH-GLASS! WQRK MODERATE CHARGES REGULAR SERVICE Our " AS-AT-'OME " SERVICE is a distinct economy 'Phone 26. 'Phone 26. JOHN FO THE HOUSE FOR WOOLLENS THE ARCADE High Street AND Inglis Street, INVERNESS. Telephone 288. reiegraphic Address—•• Woollens, Inverness." : : WAR-TIME VALUES If your insurances (of all kinds) are based on pre-war or pre- Purchase Tax Values, they may now be inadequate. In your own interests, carefully examine your insurances to-day. If you need further protection, ask the " Royal " to help. Royal Insurance^ % Company, Inverness Office : Queensgate Local Manager — W. D. Glass Elgin Wick 2 Culbard Street 16 Back Bridge Street ADVERTISEMENTS. FURNITURE We are Manufacturers of High-Grade Furniture, and hold large stocks suitable for Dining-Rooms, Lounge, Bedrooms, &c, which we can offer at Keenest Prices. CARPETS and LINOLEUMS. We invite inspection of our large range of Seamless Ax- minster and Wilton Squares, and Oriental Carpets, &c, which is the largest in the North of Scotland. Inlaid and Printed Linoleums at best Prices REMOVAL CONTRACTORS & AUCTIONEERS. Inventories and Valuations carefully made up. MACIVER & CO., 68 Church St. and 45-49 Academy St., INVERNESS. Telegrams—"Macivers, Upholsterers, Inverness." Telephone—Inverness 46. Night 854. 'Phone 568 For DYEING and DRY CLEANING The Fairfield Dyeworks TOMNAHURICH STREET INVERNESS T. HOPE, Proprietor 'Phone 722 ALEX. McLEOD WHOLESALE GROCER, EGG AND PROVISION, MERCHANT Post Office Avenue, Queensgate, Inverness HAMS, BACON and COOKED HAMS always in Stock gAJUNlfctf P5 W55 ADVERTISEMENTS. -

United States Bankruptcy Court for the District of Delaware

Case 17-10805-LSS Doc 409 Filed 11/02/17 Page 1 of 268 IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE In re: Chapter 11 UNILIFE CORPORATION, et al., 1 Case No. 17-10805 (LSS) Debtors. (Jointly Administered) AFFIDAVIT OF SERVICE STATE OF CALIFORNIA } } ss.: COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES } Darleen Sahagun, being duly sworn, deposes and says: 1. I am employed by Rust Consulting/Omni Bankruptcy, located at 5955 DeSoto Avenue, Suite 100, Woodland Hills, CA 91367. I am over the age of eighteen years and am not a party to the above- captioned action. 2. On October 30, 2017, I caused to be served the: Notice/Debtors’ Motion for Approval of Settlement of Certain Claims with Present and Former Officers and Directors, and Certain Plaintiffs and Their Counsel [Docket No. 406] Notice of Filing of Corrected Exhibit [Docket No. 407] By causing true and correct copies to be served via first-class mail, postage pre-paid to the names and addresses of the parties listed as follows: I. Docket No. 406 and Docket No. 407 to those parties listed on the annexed Exhibit A, II. Docket No. 406 (Notice Only) to those parties on the annexed Exhibit B, Also, by causing true and correct copies to be served via email to the parties listed as follows: /// 1 The Debtors in these chapter 11 cases are the following entities (the last four digits of each Debtor’s respective federal tax identification number, if any, follow in parentheses): Unilife Corporation (9354), Unilife Medical Solutions, Inc. (9944), and Unilife Cross Farm LLC (3994). -

Entertainers for 2008 Macintyre Gathering - May 24, 2008

Entertainers for 2008 MacIntyre Gathering - May 24, 2008 Below is a list of possible performers for the 2008 Gathering and some biographical information and/or their web site. The exact schedule of performances is still being prepared by the Fear An Taighe, Lorn Macintyre. Following the biographies is a list of the venues with the types of performers anticipated. : PERFORMERS INSTRUMENTALISTS 1. MICHAEL AND JOANIE GARVIN,- E- Greencourt Guest House, Oban <[email protected] Accordion and Fiddle, Oban. They have been engaged to perform before and during the Banquet while people are eating. They could also provide music for a ceilidh demo dance if that is desirable and time permits. 2. CEILIDH BAND AT OBAN, From Glasgow. Name of Band and band members to be supplied by Michael and Joanie Garvin. PIPERS 3. ARCHIE MCINTYRE, [email protected] Master piobaireachd piper, composer, England www.clandonald.org.uk/chiefs/news.html www.clandonald.org.uk/cdm00/cdm00a06.htm “Archie McIntyre was brought up on Cruachan side where he lived till he left home to join the Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders in 1957. He was taught the pipes from an early age by his father and then by the legendary Pipe Major Donald MacLeod who remained his mentor till his death. Archie is one of the very few McIntyres to bear his own Arms, is Gentleman Piper to the High Council of Clan Donald Chiefs, and the composer of may well-received tunes" At the final Gathering at Glen Noe on Sunday, he will play a new piobairoch, ‘Gathering of the MacIntyres.” 4. -

Ines the Princess What Happens Next?

INES THE PRINCESS ADVANCED WHAT HAPPENS NEXT? INFO Marie Morey DESCRIPTION Publication July 2019 A “book where you are the hero” for the little ones! Age Range 3 + years old Price £7.99 Today, it's the queen's birthday! Ines the Princess has no idea what to offer her... What will she do ? Will she find a present on Format Board Book time ? Size 220 x 180 mm KEY SELLING POINTS Extent 10 spread • A funny and interactive way for the kids to read and also be ISBN 9782733871843 the author and co-hero of the character! • On each spread, children make choices – between two possibilities, indicated by pictograms – so that the heroes can continue their adventures! • Illustrations adapted for children, with soft tones and rounded lines. ALSO AVAILABLE Other companion titles, still illustrated by Marie Morey, are formatted identically and introduces youngsters to pirates, witches and knights. NATE THE PIRATE ADVANCED WHAT HAPPENS NEXT? INFO Marie Morey DESCRIPTION Publication July 2019 A “book where you are the hero” for the little ones! Age Range 3 + years old Price £7.99 Nate the pirate dreams of adventures but doesn’t know how to find the most amazing treasure…The child helps Garrett to put Format Board Book his story together. Size 220 x 180 mm KEY SELLING POINTS Extent 10 spread • A funny and interactive way for the kids to read and also be ISBN 9782733871751 the author and co-hero of the character! • On each spread, children make choices – between two possibilities, indicated by pictograms – so that the heroes can continue their adventures! • Illustrations adapted for children, with soft tones and rounded lines. -

BBC Radio 2 Live in Newcastle

BBC Radio 2 Live In Newcastle The nation’s most listened to radio station brings a host of star names, presenters and programmes to Newcastle from Saturday 4 October-Saturday 11 October 2003 (Pictured: Sheryl Crow, Lemar, Jools Holland and Texas) Contents BBC Radio 2 Live In Newcastle On-air programming . 4 Extra events . 11 Presenter biographies Richard Allinson . 12 Paul Jones . 12 Jools Holland . 13 Frank Renton . 14 Janice Long . 15 Mike Harding . 16 Ken Bruce . 17 Fringe events . 18 www.bbc.co.uk/radio2 BBC Radio 2 Live In Newcastle On-air programming On-air programming for BBC Radio 2 Live In Newcastle All tickets are free and can be obtained special when we’re out and about, so I can by calling the Radio 2 ticket line on promise a few surprises on Saturday. It’s been a 08700 100 200. Lines are open from long time coming and I can’t wait to go back Monday 15 September, 7am-12midnight, to one of my favourite parts of the country.” seven days a week. Calls are charged at national rate. Dublin band The Thrills – Conor Deasy on vocals, Daniel Ryan on guitar/vocals and bass, Full details are listed on the Radio 2 website at Ben Carrigan on drums, Kevin Horan on www.bbc.co.uk/radio2 keyboards and Padraic McMahon on bass/vocals and guitars – played their debut London show at the Royal Albert Hall, after a Richard Allinson person invitation from Morrissey.The Thrills The Baltic get their inspiration from The Beach Boys, ESP Saturday 4 October and Burt Bacharach and are lovers of the Show: 3.30pm Doors: 2.30pm music of the West Coast of America circa the mid-Sixties and Seventies. -

Mull Historical Society Colin Macintyre 2016 Biog

Mull Historical Society/Colin MacIntyre 2016 Biog *Some reac*on to MHS’s 2016 album ‘Dear Satellite’ “Colin MacIntyre’s ability to wrap textural complexity and shard-filled lyrics in pop coa<ngs endures. Pop needs more of this.” Sunday Times “The sound of an ar<st on top form. He really does deserve to go interstellar.” Louder Than War *Some reac*on to Colin’s award-winning debut novel ‘The Le@ers of Ivor Punch’: “A truly original and enthralling novel. Ivor Punch is a magnificent crea<on and his story is mischievous, sad, funny and truthful.” - Stephen Kelman, Booker-shortlisted author of Pigeon English “Tragedy and supers<<on hang over the characters like a mist, and the sea laps against every page... Beguiling, with a keen sense of place.” - INDEPENDENT ON SUNDAY “WiJy, shocking, curious and wry, it is a mul<-faceted novel that delights at every turn... A thing of genius and wonder.” - WE LOVE THIS BOOK Colin MacIntyre – who releases under the pseudonym ‘Mull Historical Society’ – is one of the UK’s most respected songwriters & performers. A mul*-instrumentalist, programmer and producer, he is now also an Award-winning novelist, 2016 sees MacIntyre release his seventh MHS album to date: ‘Dear Satellite’. So far he has achieved two Top 20 albums and four Top 40 singles. In 2015 his debut novel, ‘The LeFers of Ivor Punch’, won the pres*gious Edinburgh InternaGonal Book FesGval First Book Award. It was also longlisted for the Guardian’s ‘Not the Booker Prize‘. Born into a family of writers, MacIntyre’s novel aQracted a 4-publisher auc*on and is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson/Orion: ‘Hilarious and hearMelt, rowdy and true, ‘The LeJers of Ivor Punch’ is a novel about fathers and sons, secrets and lies and how, some<mes, you have to leave home to know what home is.’ More Info 2015 also saw MacIntyre release a Best Of album to mark 15 years of MHS, and sign an exclusive music publishing deal with BMG/Xtra Mile Music in a landmark deal which includes new MHS albums and his en*re back catalogue, as well as his new electro pop project (more below). -

Baillie Gifford Children's Programme 11 — 27 August 2018

Baillie Gifford Children's Programme 11 — 27 August 2018 Hundreds of events for all ages! Investment managers " " When I am in a book I lose my mind. So this is an opportunity to meet the people behind the glorious chapters of the books. Young audience member FREE entry to the Book Festival village Enjoy a picnic, browse our bookshops or take part in exciting free daily activities. In the heart of Edinburgh’s West End, amid the hustle and bustle of the August crowds, stands a garden like no other. Step through the entrance gates and prepare to enter another world… Children's Programme Stomp like a dinosaur, Over 200 fun, inspiring and interactive events for children growl like a Gruffalo, Little ones can enjoy stomping like dinosaurs or growling like Gruffalos; while there are side-splitting stories for older children from Harry Hill, parade like a penguin, David Walliams and Philip Ardagh; and thrilling events for teens covering everything from love, loss and identity, to war, horror and apocalyptic survival. Kids can also get creative with Big Draws and free chat with a tea- drop-in craft activities in the Baillie Gifford Story Box (open every day drinking tiger from 11:00-16:30). Meet your author heroes From asking questions in events to getting your books signed, there are tons of opportunities to meet your favourite authors and illustrators. Most events FREE or £5.00 Scotland's LARGEST children’s bookshop With frequent book signings, special areas to share stories, and around 3,500 titles to browse and buy, the Book Festival’s Baillie Gifford Children’s Bookshop is an experience like no other. -

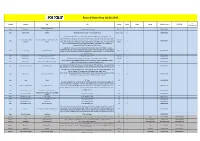

Record Store Day 18.04.2015

Record Store Day 18.04.2015 A- Vertrieb Interpret Titel Info Format Inhalt Label Genre Artikelnummer UPC/EAN Vertriebsrecht The Night We Called It Sony Bob Dylan 2 Track with picture Sleeve Vinyl 7" 1 88875074637 A Day Sony Calvin Harris Motion Record Store Day Exclusive - Vinyl Longplay 33 1/3 Vinyl LP + DLC 2 88875008971 " Coming Forth By Day "is Cassandra Wilson's moody, soulful new album showcase for contemporary yet timeless interpretations of standards associated with Lady Day. Coming Forth Cassandra Wilson / Billie "You Go to My Head" & "The Mood That By Day was produced by Nick Launay, known as Nick Cave's producer for the last decade among 10'' Vinyl Sony 1 88875069621 Holiday I'm In" many other adventurous credits. Here Cassandra reinterprets 2 of Billie’s most beautiful works of Single art, “You Go To My Head” from Coming Forth By Day and “The Mood I’m In” (previously unreleased). B-Seite die Original von Billie Holiday. 7" single of the fictional band Citizen Dick from the Cameron Crowe film "Singles" featuring members of Pearl Jam. Side A contains the band's single "Touch Me I'm Dick" and side B features Sony Citizen Dick Touch Me I'm Dick Vinyl 7" 1 88875070527 an etching of a quote about the song from Matt Dillon's character Cliff Poncier, the fictional lead singer of the band. Sony Foo Fighters Songs From The Laundry Room 4 Track 10" , Live Tracks Vinyl 10" 1 88875070561 Sony George Ezra Wanted On Voyage 12 Songs, Picture Disc Vinyl LP 1 88875073991 Sony Jimi Hendrix "Purple Haze" b/w "Freedom" Recorded Live at The Atlanta