Lipman Brochure 2009.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blanche Harris (1878-1956) Harriet Blanche Was a Suffragette in the Republican Party in the Early 20Th Century

MARCH WOMEN'S HISTORY MONTH Harriet Blanche Harris (1878-1956) Harriet Blanche was a sufFraGette in the Republican Party in the early 20th century. In 1915, she campaiGned in the city of PlainField for the riGht of African American men to vote in New Jersey. She was a stronG advocate for African American civil riGhts and women's sufFraGe. She served as president of the Women of Color SuFFraGe LeaGue of Newark. Harris spoke at rallies across the state and helped get out the vote. For example, on September 27, 1915, she addressed a mass gatherinG of African Americans in PlainField, New Jersey, urging the men in the audience to vote for the reFerendum. According to PlainField Press, Harris spoke with "eloquence and kindness, humor," explaininG that both black and white women had the riGht to representation in government. She died on February 12, 1956, and is buried in EverGreen Cemetery, Newark. MES DE HISTORIA DE LA MUJER Harriet Blanche Harris (1878-1956) Harriet Blanche fue sufragista en el Partido Republicano a principios del siglo XX. En 1915, hizo campaña en la ciudad de PlainField por el derecho de los hombres afroamericanos a votar en Nueva Jersey. Fue una firme deFensora de los derechos civiles de los afroamericanos y del sufragio femenino. Se desempeñó como presidenta de la LiGa de SuFraGio de Mujeres de Color de Newark, N.J. Harris habló en mítines en todo el estado y ayudó a obtener la votación. Por ejemplo, el 27 de septiembre de 1915, se dirigió a una reunión masiva de afroamericanos en PlainField, Nueva Jersey, instando a los hombres de la audiencia a votar por el reFeréndum. -

2014 | 2015 CONTENTS ABOUT the ABOUT EAGLETON Eagleton Institute of Politics

THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW JERSEY Eagleton Institute of Politics 2014 | 2015 CONTENTS ABOUT THE ABOUT EAGLETON Eagleton Institute of Politics HE EAGLETON INSTITUTE OF POLITICS EXPLORES STATE AND NATIONAL POLITICS 1 through research, education, and public service, linking the study of politics with its day-to-dayT practice. Th e Institute focuses att ention on how the American political system MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR works, how it changes, and how it might work bett er. 2 EDUCATION PROGRAMS 8 RESEARCH CENTERS AND PROGRAMS 16 PUBLIC PROGRAMS Wood Lawn, home of the Eagleton Institute of Politics 20 EAGLETON’S FACULTY, CENTERS AND PROGRAMS SPECIALIZE IN THE STUDY OF: ■ state legislatures and governors; DONORS ■ public opinion polling and survey research; ■ women’s political participation; ■ minority and immigrant political behavior; 22 ■ campaigns, elections and political parties; ■ ethics; ALUMNI, FACULTY, STAFF AND ■ civic education and political engagement; VISITING ASSOCIATES ■ young elected leaders and youth political participation; ■ science and politics; ■ New Jersey politics. Back Cover Th e Institute includes the Center for American Women and Politics, the Eagleton Cen- EAGLETON ONLINE ter for Public Interest Polling, and the Center on the American Governor. Eagleton also houses the Cliff ord P. Case Professorship of Public Aff airs, the Arthur J. Holland Program on Ethics in Government, the Louis J. Gambaccini Civic Engagement Series, the Senator Wynona Lipman Chair in Women’s Political Leadership, and the Albert W. Lewitt En- dowed Lecture. For Rutgers undergraduate and graduate students, Eagleton off ers a range of education programs including an undergraduate certifi cate, graduate fellowships, research assistant- ships and internships, and opportunities to interact with political practitioners. -

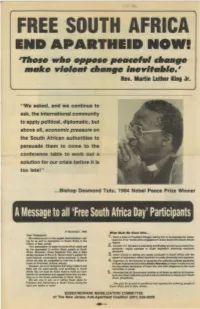

DAPA T II 0 E

REE I DAPA T II 0 e . 1 TIIose who. oppose peaceful cllaage. •ake-rloleaf-cllaage laerlfable.' Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. ''We asked, and we continue to . ask, the 'international community to apply political, diplomatic, but above all, economic pressure on ' I the South African authorities to persuade thert:' to come to the _ conference table to work out a ~- . / . solution for our crisis before it is too late!'' ... Bishop Desmond Tutu, 1984 Nobel Peace Prize Winner AMessage to all 'Free South Africa Day' Participants 9 November, 1985 What·Must Be Done Now••• Dear Participants: Send a letter to President Reagan asking him to re-evaluate the conse We welcome you to the largest demonstration call · 1. quences of his •constructive engagement' policy toward the South African ing for an end to opprf1ssion in South Africa in the regime. · history of New Jersey. Your participation in today's events will be noted well 2. Contact U.S. Senators Lauten berg and Bradley as well as you local Con by the oppressed 21-million Black people of South gressman urging passage of tough legislation enforcing economic Africa. Moreover, those di$placed from jobs in New sanctions. Jersey because of the U.S; Government's support for 3. Avoid buying or selling any goods produced in South Africa until the multi-national corporations doing business in South system of oppression called Apartherd is totally dismantled and replaced. Africa will also be compelled to note the ill effects at 4. Urge the U.S. Government to recognize the authentic _politicalleadershlp home of ill-advised policies abroad. -

Divesting from Apartheid: a Summary of State and Municipal Legislative Action on South Africa by Sandy Boyer

ACOA. American Committee on Africa Divesting from Apartheid: A Summary of State and Municipal Legislative Action on South Africa by Sandy Boyer 1982 was a year of major victories for the movement to withdraw public funds from companies whose investment in South Africa subsidizes the apartheid system. Massachusetts, Michigan, Connecticut and the cities of Philadelphia, Wilmington and Grand Rapids all enacted legislation that will force the divestment of up to $300 million. The Massachusetts bill, which requires state pension funds to sell all stocks and bonds in companies doing business in South Africa, is the most comprehensive divestment legislation yet passed by any state. Philadelphia is the first major American city to pass a divestment ordinance. Both the Massachusetts and the Philadelphia bills call for full divestment of pension funds, and both are being used as model legislation in campaigns around the country. Already in 1983, legislative action against apartheid is being worked on in 21 states and 8 cities and counties. The following summary provides detailed information on this legislation. We hope it will be useful not only to legislators, but to many concerned people from the churches, the unions, and civil rights, community and campus organizations who have been working to end public investment in South African racism. We hope this summary will help you in your efforts to win many more victories in 1983. On May 1, 1980, the Citizens Committee on Responsible ALABAMA Investment which had been created to carry out the refer STATE ACTION: State Representative James Buskey will endum mandate, submitted its 45 page report. -

THE WESTFIELD LEADER the Leading and Most Widely Circulated Weekly Ixewnpaper in Union County A

o • cr> _ o * I- > THE WESTFIELD LEADER The leading and Most Widely Circulated Weekly iXewnpaper In Union County a PI Publisher) Second ClfU)*! Pc>Hl««c Palri WESTFIELD, NEW JERSEY. THURSDAY, APRIL 17, 1980 wry Thursday 22 Pages—20 Cents NINETIET on >.37 UJ O.-J More than 100 School Board Appoints 444, Neighborhood "Watchers" Learn about Anti-Crime Surveillance Cuts 22 from '80-81 Staff More lhan 100 pairs of timers in discouraging questions that will be an- residents to be more aware "eyes and ears" turned out burglars? swered for others residents of anything unusual they The Westfield Ficjard of approved by townspeople in students and numbers and fourth grade teacher, :M) struclion of exhaust and at Thursday night's Neigh- —On what kinds of things as well, as the Neighborhood might see in their own Education appointed 4<14 the ltlHO-81 school budget for courses selected by years; Melissa Knuralle. fume systems in Roosevelt borhood Watch meeting to should residents call the Watch program progresses neighborhoods. teachers, nurses, guidance next year totals 22 staff secondary school students,! Edison Junior High School and Edison Junior High see and hear more about (he police? to penetrate into hopefully, Councilwoman Betty List, counselors and rjfiici' staff positions: (hree ad- on financial resources and social studies teacher, 40 Schools and the resurfacing town's new c ill 2 en -police —Are neighborhood youths each of Westfield's who, as Public Safety members for (he jwu-Hl ministrators; two on an ongoing .staff years; and Margaret of floors and stairways at cooperative effort to help estimated 10,000 homes. -

Equal Justice Awards Reception 2017 Program

The Legal Services of New Jersey 2017 EQUAL JUSTICE AWARDS RECEPTION Celebrating Those Who Advance Justice and Fairness Under Law The Grounds for Sculpture Hamilton Township, New Jersey 6:00–9:00 p.m. June 7, 2017 THE NEW JERSEY LEGAL SERVICES SYSTEM Legal Services of New Jersey Edison REGIONAL PROGRAMS South Jersey Legal Services Offices in Atlantic, Burlington, Camden, Cape May, Cumberland, Gloucester, Monmouth, Ocean, and Salem Counties Central Jersey Legal Services Offices in Mercer, Middlesex, and Union Counties Essex-Newark Legal Services Newark Northeast New Jersey Legal Services Offices in Bergen, Hudson, and Passaic Counties Legal Services of Northwest Jersey Offices in Hunterdon, Morris, Somerset, Sussex, and Warren Counties This event is entirely supported by private contributions. Legal Services of New Jersey is deeply grateful for the generous contributions of the following sponsors. The amounts signified by the various sponsorship levels may be found at www.lsnj.org. GUARDIAN OF EQUAL JUSTICE EQUAL JUSTICE LEADER EQUAL JUSTICE PARTNER EQUAL JUSTICE SUPPORTER John L. McGoldrick McCreedy & Cox LEGAL SERVICES OF NEW JERSEY BOARD OF TRUSTEES Deborah T. Poritz, Esq. Douglas S. Eakeley, Esq. Drinker Biddle & Reath LLP Lowenstein Sandler LLP Chairperson Zulima V. Farber, Esq. Cynthia M. Jacob, Esq. Fisher & Phillips LLP Michael K. Furey, Esq. Vice Chairperson Day Pitney Virginia A. Long, Esq. Ross A. Lewin, Esq. Fox Rothschild LLP Drinker Biddle & Reath LLP Vice Chairperson Regina C. Little, Esq. Stephen M. Orlofsky, Esq. National Treasury Employees Union Blank Rome LLP Vice Chairperson Edwin J. McCreedy, Esq. McCreedy & Cox Karol Corbin Walker, Esq. LeClairRyan John L. McGoldrick, Esq. -

6-Weequahic Newsletter Spring 2002.Lwp

WHS ALUMNI ASSOCIATION training school. Many of these kids come 279 Chancellor Avenue from impoverished homes. Many have little Newark, NJ 07112 A Meaningful Office: (973) 923-3133 or no emotional support from anyone. Fax: (973) 923-3143 Way To Say Thanks Although they qualify to be accepted, many [email protected] cannot afford the books, no less the tuition. www.weequahicalumni.org By Hal Braff, Co-President, So this is a two-pronged appeal. If you are WHS Alumni Association Executive Director: organizing a reunion, build enough into the Class of 1952 Phil Yourish, 1964 charge so that you can offer the Alumni Association a scholarship in your class’ name. There was no way I could have imagined, What greater tribute could there be than to Co-Presidents: receiving my diploma from Michael Conover, give some worthy youngsters a chance for a Harold Braff, 1952 Principal of Weequahic High School fifty brighter future in the name of your class. Faith Howard, 1982 years ago, that my experience there would be so impactful. My life then was still being Treasurer: If your memories of growing up honor your shaped. I was unformed - naive. I took for Sheldon Bross, 1955 parents or teachers or friends who made granted loving, caring parents and an excellent significant contributions to your development, Secretary: education system as I did the safety and consider paying tribute to them by security of reliable friends and a community Adilah Quddus, 1971 establishing a scholarship fund in their name of families much like mine. through the Alumni Association. Committee Chairs: Now at 67, grateful for the wonderful life I’ve Events: In doing so a youngster will get an otherwise been so privileged to lead, it is far clearer to Faith Howard, 1982 unavailable opportunity and you can enjoy the me how very fortunate it was for me to have satisfaction of knowing that your tax-free gift Membership: grown up in Newark and to have attended will assure that the name of someone Adilah Quddus, 1971 such a remarkable high school. -

Eagleton Institute of Politics

ALUMNI BALLOT CAMPAIGN CANDIDATE CONSTITUTION CONTEXT CONTRIBUTE CONVERSATION DEBATE DE MOCRACY DISCUSS ELECTION ENGAGEMENT ETHICS FACULTY INTERNSHIP INDEPENDENT MILLENNIAL NA- TIONAL NEW JERSEY PARTICIPATE PUBLIC SERVICE RESPONSIBILITY SECURITY SPEAKERS TEACH UNDERGRA UATE VOTERS STATE LEGISLATURE GRADUATE FELLOWSHIP WASHINGTON, DC ALUMNI BALLOT CAMPAIGN CANDIDATE CONSTITUTION CONTEXT CONTRIBUTE CONVERSATION DEBATE DEMOCRACY DISCUSS ELECTIO ENGAGEMENT ETHICS FACULTY INTERNSHIP INDEPENDENT MILLENNIAL NATIONAL NEW JERSEY PARTICIPAT PUBLIC SERVICE RESPONSIBILITY SECURITY SPEAKERS TEACH UNDERGRADUATE VOTERS STATE LEGISLATU GRADUATE FELLOWSHIP WASHINGTON, DC ALUMNI BALLOT CAMPAIGN CANDIDATE CONSTITUTION CONTEX CONTRIBUTE CONVERSATION DEBATE DEMOCRACY DISCUSS ELECTION ENGAGEMENT ETHICS FACULTY IN- TERNSHIP INDEPENDENT MILLENNIAL NATIONAL NEW JERSEY PARTICIPATE PUBLIC SERVICE RESPONSIBILITY SECURITY SPEAKERS TEACH UNDERGRADUATE VOTERS STATE LEGISLATURE GRADUATE FELLOWSHIP WASH INGTON, DC ALUMNI BALLOT CAMPAIGN CANDIDATE CONSTITUTION CONTEXT CONTRIBUTE CONVERSATION DEBATE DEMOCRACY DISCUSS ELECTION ENGAGEMENT ETHICS FACULTY INTERNSHIP INDEPENDENT MIL- LENNIAL NATIONAL NEWEAGLETON JERSEY PARTICIPATE PUBLIC INSTITUTE SERVICE RESPONSIBILITY OF POLITICS SECURITY SPEAKERS TEACH UNDERGRADUATE VOTERS STATE LEGISLATURE GRADUATE FELLOWSHIP WASHINGTON, DC ALUMNI BALLOT CAMPAIGN CANDIDATE CONSTITUTION CONTEXT CONTRIBUTE CONVERSATION DEBATE DEMOCRACY DIS- CUSS ELECTION ENGAGEMENT ETHICS FACULTY INTERNSHIP INDEPENDENT MILLENNIAL NATIONAL NEW 2016–2017 JERSEY -

New Jersey Legislative Black and Latino Caucus a Report On

You Are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library New Jersey Legislative Black and Latino Caucus A Report on Discriminatory Practices Within the New Jersey State Police August 1999 You Are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library Membership of the New Jersey Legislative Black and Latino Caucus Chairman: Assemblyman Joseph Charles, Jr. District 31 (Hudson) Senators: Senator Wayne R. Bryant District 5 (Camden) Senator Wynona Lipman (Deceased) District 29 (Essex) Senator Sharpe James District 29 (Essex) Senator Ronald L. Rice District 28 (Essex) Senator Shirley K. Turner District 15 (Mercer) Assemblymembers: Assemblyman Wilfredo Caraballo District 28 (Essex) Assemblyman Herbert C. Conaway, MD District 7 (Burlington) Assemblywoman Nilsa Cruz-Perez District 5 (Camden) Assemblyman Raul Garcia District 33 (Hudson) Assemblywoman Nia H. Gill District 27 (Essex) Assemblyman Jerry Green District 17 (Middlesex) Assemblyman LeRoy J. Jones, Jr. District 27 (Essex) Assemblyman William D. Payne District 29 (Essex) Assemblywoman Nellie Pou District 35 (Passaic) Assemblyman Tom Smith District 11 (Monmouth) Assemblyman Craig A. Stanley District 28 (Essex) Assemblyman Alfred E. Steele District 35 (Passaic) Assemblyman Donald Tucker District 29 (Essex) Assemblywoman Bonnie Watson Coleman District 15 (Mercer) The Caucus extends its thanks and appreciation to all of the support staff that assisted in the hearings and the production of this report. You Are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library TABLE OF -

FY17 Appropriations Handbook

APPROPRIATIONS HANDBOOK STATE OF NEW JERSEY FISCAL YEAR 2016 --2017 DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY OFFICE OF MANAGEMENT AND BUDGET Ford M. Scudder David Ridolfino Acting State Treasurer Acting Director, Office of Management and Budget NEW JERSEY STATE LEGISLATURE BUDGET AND APPROPRIATIONS COMMITTEES SESSION OF 2016 SENATE BUDGET AND APPROPRIATIONS COMMITTEE Paul A. Sarlo (D), 36th District (Parts of Bergen and Passaic), Chairman Brian P. Stack (D), 33rd District (Part of Hudson), Vice-Chairman Jennifer Beck (R), 11th District (Part of Monmouth) Anthony R. Bucco (R), 25th District (Parts of Morris and Somerset) Sandra B. Cunningham (D), 31st District (Part of Hudson) Patrick J. Diegnan Jr. (D), 18th District (Part of Middlesex) Linda R. Greenstein (D), 14th District (Parts of Mercer and Middlesex) Kevin J. O’Toole (R), 40th District (Parts of Bergen, Essex, Morris and Passaic) Steven V. Oroho (R), 24th District (Sussex and parts of Morris and Warren) Nellie Pou (D), 35th District (Parts of Bergen and Passaic) M. Teresa Ruiz (D), 29th District (Part of Essex) Samuel D. Thompson (R), 12th District (Parts of Burlington, Middlesex, Monmouth and Ocean) Jeff Van Drew (D), 1st District (Cape May and parts of Atlantic and Cumberland) GENERAL ASSEMBLY BUDGET COMMITTEE Gary S. Schaer (D), 36th District (Parts of Bergen and Passaic), Chairman John J. Burzichelli (D), 3rd District (Salem and parts of Cumberland and Gloucester) Vice-Chairman Anthony M. Bucco (R), 25th District (Parts of Morris and Somerset) John DiMaio (R), 23rd District (Parts of Hunterdon, Somerset and Warren) Gordon M. Johnson (D), 37th District (Part of Bergen) John F. McKeon (D), 27th District (Parts of Essex and Morris) Raj Mukherji (D), 33rd District (Part of Hudson) Elizabeth Maher Muoio (D), 15th District (Parts of Hunterdon and Mercer) Declan J. -

Drug Abuse (7)” of the James M

The original documents are located in Box 11, folder “Drug Abuse (7)” of the James M. Cannon Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 11 of the James M. Cannon Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON MEETING WITH THE MEXICAN ATTORNEY GENERAL Tuesday, June 8, 1976 4:00 p.m. (10 minutes} Oval Office From: Jim Canna~ I. PURPOSE To thank the Mexican Attorney General {Pedro Ojeda-Paullada} for the excellent cooperation he and his government have shown in the fight against drug trafficking and to urge continued close cooperation between our two countries. · II. BACKGROUND, PARTICIPANTS & PRESS PLAN A. Background: Mexico is the source of an estimated 80 to 90 per cent of the heroin and more than half of the marihuana available in the United States. Attorney General Ojeda-Paullada has been a strong ally these past several years as the United States and Mexico have worked to suppress drug traffic. -

New Jersey Legislative Black and Latino Caucus

New Jersey Legislative Black and Latino Caucus A Report on Discriminatory Practices Within the New Jersey State Police August 1999 Membership of the New Jersey Legislative Black and Latino Caucus Chairman: Assemblyman Joseph Charles, Jr. District 31 (Hudson) Senators: Senator Wayne R. Bryant District 5 (Camden) Senator Wynona Lipman (Deceased) District 29 (Essex) Senator Sharpe James District 29 (Essex) Senator Ronald L. Rice District 28 (Essex) Senator Shirley K. Turner District 15 (Mercer) Assemblymembers: Assemblyman Wilfredo Caraballo District 28 (Essex) Assemblyman Herbert C. Conaway, MD District 7 (Burlington) Assemblywoman Nilsa Cruz-Perez District 5 (Camden) Assemblyman Raul Garcia District 33 (Hudson) Assemblywoman Nia H. Gill District 27 (Essex) Assemblyman Jerry Green District 17 (Middlesex) Assemblyman LeRoy J. Jones, Jr. District 27 (Essex) Assemblyman William D. Payne District 29 (Essex) Assemblywoman Nellie Pou District 35 (Passaic) Assemblyman Tom Smith District 11 (Monmouth) Assemblyman Craig A. Stanley District 28 (Essex) Assemblyman Alfred E. Steele District 35 (Passaic) Assemblyman Donald Tucker District 29 (Essex) Assemblywoman Bonnie Watson Coleman District 15 (Mercer) The Caucus extends its thanks and appreciation to all of the support staff that assisted in the hearings and the production of this report. TABLE OF CONTENTS Part I - Overview........................................................................................................ 1 Background...................................................................................................