Cecil C. Konijnendijk Kjell Nilsson Thomas B. Randrup Jasper Schipperijn (Eds.) Urban Forests and Trees Cecil C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

F R Id T Jo F Nansens in St It U

VOLOS -R" RECEIVED WO* 2 9 899 oari Olav Schram Stokke Subregional Cooperation and Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment: The Barents Sea INSTITUTT POLOS Report No. 5/1997 NANSENS Polar Oceans Reports FRIDTJOF 3 1-05 FRIDTJOF NANSENS INSTITUTE THE FRIDTJOF NANSEN INSTITUTE Olav Schram Stokke Subregional Cooperation and Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment: The Barents Sea POLOS Report No. 5/1997 ISBN 82-7613-235-9 ISSN 0808-3622 ---------- Polar Oceans Reports a publication series from Polar Oceans and the Law of the Sea Project (POLOS) Fridtjof Nansens vei 17, Postboks 326, N-1324 Lysaker, Norway Tel: 67111900 Fax: 67111910 E-mail: [email protected] Bankgiro: 6222.05.06741 Postgiro: 5 08 36 47 © The Fridtjof Nansen Institute Published by The Fridtjof Nansen Institute DISCLAIMER Portions of this document may be illegible in electronic image products. Images are produced from the best available original document. Polar Oceans and the Law of the Sea Project (POLOS) POLOS is a three-year (1996-98) international research project in international law and international relations, initiated and coordinated by the Fridtjof Nansen Institute (FNI). The main focus of POLOS is the changing conditions in the contemporary international community influencing the Arctic and the Antarctic. The primary aim of the project is to analyze global and regional solutions in the law of the sea and ocean policy as these relate to the Arctic and Southern Oceans, as well as to explore the possible mutual relevance of the regional polar solutions, taking into consideration both similarities and differences of the two polar regions. -

CV Oscar Kjell Phd in Psychology, Department of Psychology, Lund University ______

CV Oscar Kjell PhD in Psychology, Department of Psychology, Lund University _________________________________________________________________________________ Personal information Nationality Swedish Date of birth November 28, 1982 Phone +46 70 8803292 Email [email protected] Website www.oscarkjell.se; www.r-text.org Twitter @OscarKjell Address Department of Psychology, Box 117, 221 00 Lund University, Sweden I develop and validate ways to measure psychological constructs using psychometrics and artificial intelligence (AI) such as natural language processing and machine learning. I am the developer of the r-package text (www.r-text.org), which provides powerful functions tailored to analyse text data for testing research hypotheses in social and behavior sciences. Using AI, as compared with traditional rating scales, we can (more) accurately measure psychological constructs; differentiate between similar constructs (such as worry and depression); as well as depict the content individuals use to describe their states of mind. I am, for example, applying these methods to better understand subjective well-being and to compare harmony in life versus satisfaction with life. I am particularly interested in sustainable well-being; how pursuing different types of well-being might bring about different social and environmental consequences. I am a co-founder of WordDiagnostics, where we apply these AI methods in a decision support system for diagnosing psychiatric disorders. Education 2012 – 2018 PhD in Psychology (Lund University, Sweden) -

Does the Nordic Region Speak with a FORKED Tongue?

Does the Nordic Region Speak with a FORKED Tongue? The Queen of Denmark, the Government Minister and others give their views on the Nordic language community KARIN ARVIDSSON Does the Nordic Region Speak with a FORKED Tongue? The Queen of Denmark, the Government Minister and others give their views on the Nordic language community NORD: 2012:008 ISBN: 978-92-893-2404-5 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.6027/Nord2012-008 Author: Karin Arvidsson Editor: Jesper Schou-Knudsen Research and editing: Arvidsson Kultur & Kommunikation AB Translation: Leslie Walke (Translation of Bodil Aurstad’s article by Anne-Margaret Bressendorff) Photography: Johannes Jansson (Photo of Fredrik Lindström by Magnus Fröderberg) Design: Mar Mar Co. Print: Scanprint A/S, Viby Edition of 1000 Printed in Denmark Nordic Council Nordic Council of Ministers Ved Stranden 18 Ved Stranden 18 DK-1061 Copenhagen K DK-1061 Copenhagen K Phone (+45) 3396 0200 Phone (+45) 3396 0400 www.norden.org The Nordic Co-operation Nordic co-operation is one of the world’s most extensive forms of regional collaboration, involving Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and the Faroe Islands, Greenland, and Åland. Nordic co-operation has firm traditions in politics, the economy, and culture. It plays an important role in European and international collaboration, and aims at creating a strong Nordic community in a strong Europe. Nordic co-operation seeks to safeguard Nordic and regional interests and principles in the global community. Common Nordic values help the region solidify its position as one of the world’s most innovative and competitive. Does the Nordic Region Speak with a FORKED Tongue? The Queen of Denmark, the Government Minister and others give their views on the Nordic language community KARIN ARVIDSSON Preface Languages in the Nordic Region 13 Fredrik Lindström Language researcher, comedian and and presenter on Swedish television. -

Curriculum Vitae

Dressinvägen 6 SE-245 63 Hjärup Sweden Phone: +46 40460522 e-mail: [email protected] Curriculum vitae Dr. Kjell Nilsson Member of the Association of Danish Landscape Architects and the Swedish Association of Architects Born: September 2, 1952 Family: Married to Karin Andersson, Jens (b. 1985) and Emma (b. 1987) Languages: Swedish, Danish, English and German Since February 1, 2013, Kjell Nilsson is director of Nordregio, a research institute under the Nordic Council of Ministers. He has also been Head of the Department of Parks and Urban Landscape and Deputy Director of the Danish Centre for Forest, Landscape and Planning at the Danish Ministry for the Environment and the University of Copenhagen, and Senior Advisor at Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. In the 1980’s, together with colleagues Eivor Bucht and Ole Andersson, he established the Movium-secretariat at the Swedish University of Agricultural Science. As principal responsible for Movium's extension service, Kjell Nilsson laid the foundation for what has today developed into a think tank for urban development and a fruitful dialogue between researchers and practitioners. Since 1995, Kjell Nilsson has lead interdisciplinary landscape research projects both nationally and internationally. “Boundaries in the Landscape” under the Danish research programme “Man, Landscape and Biodiversity”, “The Landscape as a Resource for Health and Sustainable Development in the Sound Region” and PLUREL (Peri-urban Land Use Relationships – Strategies and Sustainability Impact Assessment Tools for Urban-rural Linkages) – an integrated project under the 6th EU Framework Program, are examples of this. A second focus of Kjell Nilsson’s research activities is on Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. -

20Th Anniversary Celebration

The Saga of New Sweden Cultural Heritage Society Portland, Oregon October 2009 Editor: Leif Rosqvist Newsletter Volume 94 Once upon a time… The Swedish, Finnish and US governments declared a celebration honoring the 350th anniversary of the establishment in 1638 of the first Swedish colony on American shores. The anniversary year was 1988. The US Congress passed Public Law 99-304 designating 1988 as the “Year of New Sweden” and authorized President Reagan to issue an official proclamation in observance of the year. President Reagan declared, “Swedish Americans have won a place in the history and heritage of the United States, and they continue their tradition of notable achievements today. Two Swedish Americans associated prominently with the American Revolution were John Morton of Pennsylvania, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and John Hanson of Maryland, who presided over the Continental Congress in 1781 and 1782. More than a million Swedes came to the United States between,1845 and 1910, and more than four million Americans today have Swedish ancestry. We can all be truly proud of the contributions of Swedish Americans to our be- loved land, of the close ties between the United States and Sweden over the years, and the devotion to democracy that our peoples share. Now, therefore, I, Ronald Reagan, President of the United States of America, do hereby pro- claim 1988 as the Year of New Sweden. I call upon the Governors of the sev- eral states, local officials, and the people of the United States to observe this year with appropriate ceremonies and activities.” The celebrations of New Sweden ’88 reminded us all of the significance and Kalmar Nyckel impact Swedish and Finnish immigration had on the US. -

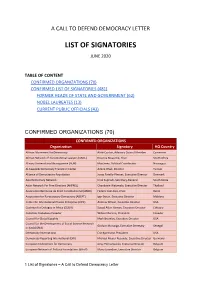

List of Signatories June 2020

A CALL TO DEFEND DEMOCRACY LETTER LIST OF SIGNATORIES JUNE 2020 TABLE OF CONTENT CONFIRMED ORGANIZATIONS (70) CONFIRMED LIST OF SIGNATORIES (481) FORMER HEADS OF STATE AND GOVERNMENT (62) NOBEL LAUREATES (13) CURRENT PUBLIC OFFICIALS (43) CONFIRMED ORGANIZATIONS (70) CONFIRMED ORGANIZATIONS Organization Signatory HQ Country African Movement for Democracy Ateki Caxton, Advisory Council Member Cameroon African Network of Constitutional Lawyers (ANCL) Enyinna Nwauche, Chair South Africa Alinaza Universitaria Nicaraguense (AUN) Max Jerez, Political Coordinator Nicaragua Al-Kawakibi Democracy Transition Center Amine Ghali, Director Tunisia Alliance of Democracies Foundation Jonas Parello-Plesner, Executive Director Denmark Asia Democracy Network Ichal Supriadi, Secretary-General South Korea Asian Network For Free Elections (ANFREL) Chandanie Watawala, Executive Director Thailand Association Béninoise de Droit Constitutionnel (ABDC) Federic Joel Aivo, Chair Benin Association for Participatory Democracy (ADEPT) Igor Botan, Executive Director Moldova Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE) Andrew Wilson, Executive Director USA Coalition for Dialogue in Africa (CODA) Souad Aden-Osman, Executive Director Ethiopia Colectivo Ciudadano Ecuador Wilson Moreno, President Ecuador Council for Global Equality Mark Bromley, Executive Director USA Council for the Development of Social Science Research Godwin Murunga, Executive Secretary Senegal in (CODESRIA) Democracy International Eric Bjornlund, President USA Democracy Reporting International -

Made in China, Sold in Norway: Local Labor Market Effects of an Import Shock

IZA DP No. 8324 Made in China, Sold in Norway: Local Labor Market Effects of an Import Shock Ragnhild Balsvik Sissel Jensen Kjell G. Salvanes July 2014 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor Made in China, Sold in Norway: Local Labor Market Effects of an Import Shock Ragnhild Balsvik Norwegian School of Economics Sissel Jensen Norwegian School of Economics Kjell G. Salvanes Norwegian School of Economics, IZA and CEEP Discussion Paper No. 8324 July 2014 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 E-mail: [email protected] Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit organization supported by Deutsche Post Foundation. The center is associated with the University of Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its international network, workshops and conferences, data service, project support, research visits and doctoral program. IZA engages in (i) original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. -

Summary of Discussion Topics the Scandinavia National Advisory Board Met in October and in February

Scandinavia National Advisory Board Crown Council Report April 2013 Summary of Discussion Topics The Scandinavia National Advisory Board met in October and in February. In those meetings the board worked on creating a Gustavus Swedish heritage and connections statement. The Gustavus mission statement says, “Gustavus Adolphus College is a church-related, residential liberal arts college firmly rooted in its Swedish and Lutheran heritage.” Online at the Gustavus website is a statement about the meaning of the College’s Lutheran heritage. There has never been such a statement about the meaning of the College’s Swedish heritage. Below is the statement the SNAB has developed. This statement will be posted online, followed by an extensive list of connections between the College and Scandinavia. The list of connections is still in progress. See the start of the list below. Gustavus, Sweden and Scandinavia: Heritage and Connections Gustavus celebrates its deep and ever-expanding relations with the people of Sweden, Scandinavia and the Baltic Sea region. In 1862 Swedish Lutheran immigrants in Minnesota started the school which would, in 1876, be named Gustavus Adolphus College (Link to history webpage). Gustavus continues to embrace the values shared by its visionary founders in their commitment to educate students for community benefit and personal development. Of course much has changed in Sweden and at Gustavus since 1862. Many new areas of shared interest, rich relationships and deep connections have been and continue to be developed between Gustavus and organizations and people in Scandinavia. These provide rich opportunities for learning that greatly enhance the Gustavus experience for current students of all faiths, interests and backgrounds. -

Swedish American Genealogy and Local History: Selected Titles at the Library of Congress

SWEDISH AMERICAN GENEALOGY AND LOCAL HISTORY: SELECTED TITLES AT THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled and Annotated by Lee V. Douglas CONTENTS I.. Introduction . 1 II. General Works on Scandinavian Emigration . 3 III. Memoirs, Registers of Names, Passenger Lists, . 5 Essays on Sweden and Swedish America IV. Handbooks on Methodology of Swedish and . 23 Swedish-American Genealogical Research V. Local Histories in the United Sates California . 28 Idaho . 29 Illinois . 30 Iowa . 32 Kansas . 32 Maine . 34 Minnesota . 35 New Jersey . 38 New York . 39 South Dakota . 40 Texas . 40 Wisconsin . 41 VI. Personal Names . 42 I. INTRODUCTION Swedish American studies, including local history and genealogy, are among the best documented immigrant studies in the United States. This is the result of the Swedish genius for documenting almost every aspect of life from birth to death. They have, in fact, created and retained documents that Americans would never think of looking for, such as certificates of change of employment, of change of address, military records relating whether a soldier's horse was properly equipped, and more common events such as marriage, emigration, and death. When immigrants arrived in the United States and found that they were not bound to the single state religion into which they had been born, the Swedish church split into many denominations that emphasized one or another aspect of religion and culture. Some required children to study the mother tongue in Saturday classes, others did not. Some, more liberal than European Swedish Lutheranism, permitted freedom of religion in the new country and even allowed sects to flourish that had been banned in Sweden. -

Discussion at Augsburg with Kjell-Magne Bondevik

Kjell Magne Bondevik, former Prime Minister of Norway, received an Honorary Doctor of Humane Letters, Honoris Causa, and gave the Commencement Address at Augsburg College, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States of America. This informal discussion was held the day before Commencement. THE TANDEM PROJECT http://www.tandemproject.com. [email protected] UNITED NATIONS, HUMAN RIGHTS, FREEDOM OF RELIGION OR BELIEF The Tandem Project is a UN NGO in Special Consultative Status with the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations Separation of Religion or Belief and State PRELIMINARY & INFORMAL DISCUSSION AT AUGSBURG COLLEGE WITH FORMER PRIME MINISTER KJELL MAGNE BONDEVIK PASTOR IN THE LUTHERAN CHURCH OF NORWAY FOUNDER & PRESIDENT THE OSLO CENTER FOR PEACE & HUMAN RIGHTS ______________________________________________________________________________ AGENDA 1. The Question 2. The Issue & Impasse 3. Somalia Constitutions 4. Norway Constitution 5. The Opportunity __________________________________________________________________________________ I. THE QUESTION CAN A PERSON WHO IS MUSLIM CHOOSE A RELIGION OTHER THAN ISLAM? “Can a person who is Muslim choose a religion other than Islam? When Egypt’s grand mufti, Ali Gomaa, pondered that dilemma in an article published in 2008, many of his co-religionists were shocked that the question could even be asked. And they were even more scandalized by his conclusion. The answer, he wrote, was yes, they can, in the light of three verses in the Koran: first, ”unto you your religion, an unto me my religion” -

LTJ-Fakultetens Faktablad Fact Sheet from LTJ Faculty 2010:18

LTJ-fakultetens faktablad Fact sheet from LTJ faculty 2010:18 ALNARP Facts from Department of Landscape Architecture, Alnarp Icelandic medieval monastic sites – vegetation and flora, cultural plants and relict plants, contemporary plant-names Inger Larsson and Kjell Lundquist Were there monasteries in Iceland in the Middle Ages? How many were there? Where were they located, how were they built and, above all, were there any adjacent monastic gardens? The Nordic project “Icelandic medieval monastic sites – vege- tation and flora, cultural plants and relict plants, contemporary plant-names” will try to contribute to answering these questions that can be sum- marized as follows: What cultivated plants and garden plants were known and used in the medie- val Icelandic monastic context? Will new research into the relatively uninvestigated and largely un- touched medieval Icelandic monastic sites modify our knowledge of the form and plant life of the Nordic monastic garden? The project has its starting point in the archaeo- botanic findings of some medicinal plants, such as a species in the onion genus (Allium sp.), stinging nettle (Urtica dioica) and greater plantain (Plan- tago major), made during the excavation of an Augustinian monastery, Skriðuklaustur in Fljóts- dalur, eastern Iceland (occupied 1493–1550) led by archaeologist Steinunn Kristjánsdóttir at the University of Iceland (fig. 3). 1 Figure 1. Helgafellklaustur (1184–1551), an Augustinian monastery, situated some kilometers south of Stykkishól- Background mur in north-west Iceland. The picture is taken from the top of the 73 meters high Helgafell (the holy mountain). The According to tradition Celtic anchorites monastic site is supposed to have been located at the foot of Helgafell, between the mountain and the present church. -

Curriculum Vitae – December, 2018 KJELL YNGVE TÖRNBLOM

Curriculum Vitae – December, 2018 KJELL YNGVE TÖRNBLOM Present addresses: Transdisciplinarity Lab (TdLab) Majorsgatan 8 Department of Environmental Systems Science, 41308 Göteborg ETH Zürich, Switzerland Sweden (Fall semesters) Contact information: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Phone numbers: Cell: +46-708 627578 Fall semesters, ETH Zürich office: +41-44-6324330 Citizenships: Sweden and USA. EDUCATION 1981. DOCENT, Social Psychology, University of Göteborg, Göteborg, Sweden. (A post- doctoral degree requiring published research minimally equivalent to a second Ph.D dissertation.) 1971. Ph.D., Sociology/Social Psychology, University of Missouri-Columbia, MO, USA. Ph.D. Dissertation: Own expectations and behavior: Theory and experiments. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri-Columbia, 1971 (Bruce J. Biddle, Supervisor). 1968. M.A., Sociology (Educational Psychology Minor), University of Göteborg, Göteborg, Sweden. M.A. Thesis: Sexual motivation: Social activity and sexual activity. Göteborg: University of Göteborg, 1968 (Joachim Israel, Supervisor). 1964. High School Diploma (Studentexamen), Söderhamns Högre Allmänna Läroverk, Söderhamn, Sweden. 1 EMPLOYMENT Fall 2018: Guest Professor, Department of Environmental Systems Science, USYS TdLab, ETH Zürich, Switzerland (15/9-15/12). Fall 2017: Guest Professor, Department of Environmental Systems Science, USYS TdLab, ETH Zürich, Switzerland (18/9-18/12). Fall 2016: Guest Professor, Department of Environmental Systems Science, USYS TdLab, ETH Zürich, Switzerland (15/9-20/12). Fall 2015: Guest Professor, Department of Environmental Systems Science, USYS TdLab, ETH Zürich, Switzerland (15/9-20/12). 2000 - 2013: Professor, Department of Behavioral Sciences, Social Psychology Unit, University of Skövde, Sweden. 1996-1997 and Spring 1999: Visiting Professor, Department of Behavioral Sciences, Social Psychology Unit, University of Skövde, Sweden.