VIII. Eight Basic Pitfalls: a Checklist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Demetrius Poliorcetes and the Hellenic League

DEMETRIUSPOLIORCETES AND THE HELLENIC LEAGUE (PLATE 33) 1. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND D JURING the six years, 307/6-302/1 B.C., issues were raised and settled which shaped the course of western history for a long time to come. The epoch was alike critical for Athens, Hellas, and the Macedonians. The Macedonians faced squarely during this period the decision whether their world was to be one world or an aggregate of separate kingdoms with conflicting interests, and ill-defined boundaries, preserved by a precarious balance of power and incapable of common action against uprisings of Greek and oriental subjects and the plundering appetites of surrounding barbarians. The champion of unity was King Antigonus the One- Eyed, and his chief lieutenant his brilliant but unstatesmanlike son, King Demetrius the Taker of Cities, a master of siege operations and of naval construction and tactics, more skilled in organizing the land-instruments of warfare than in using them on the battle field. The final campaign between the champions of Macedonian unity and disunity opened in 307 with the liberation of Athens by Demetrius and ended in 301 B.C. with the Battle of the Kings, when Antigonus died in a hail of javelins and Demetrius' cavalry failed to penetrate a corps of 500 Indian elephants in a vain effort to rescue hinm. Of his four adversaries King Lysimachus and King Kassander left no successors; the other two, Kings Ptolemy of Egypt and Seleucus of Syria, were more fortunate, and they and Demetrius' able son, Antigonus Gonatas, planted the three dynasties with whom the Romans dealt and whom they successively destroyed in wars spread over 44 years. -

The Fate and Power of Heroic Bones and the Politics of Bone Transfer in Ancient Israel and Greece*

Digital Commons @ George Fox University College of Christian Studies 2013 The aF te and Power of Heroic Bones and the Politics of Bone Transfer in Ancient Israel and Greece Brian R. Doak George Fox University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ccs Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, and the Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Doak, Brian R., "The aF te and Power of Heroic Bones and the Politics of Bone Transfer in Ancient Israel and Greece" (2013). College of Christian Studies. Paper 1. http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ccs/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Christian Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. The Fate and Power of Heroic Bones and the Politics of Bone Transfer in Ancient Israel and Greece* Brian R. Doak George Fox University Introduction Tucked away in the Hebrew Bible at the end of 1 Samuel and then resumed near the end of 2 Samuel is a provocative tale recounting the final fate of Saul, Israel’s first king.1 At the beginning of this two-part narrative (1 Sam 31:1), we find Saul atop Mount Gilboa, badly wounded by Philistine archers and nearly dead. Fearing the Philistine armies will rush upon him and continue the humiliation—perhaps by stabbing him repeatedly while still alive, as Saul suggests in 31:4, or something *This paper was first presented in abbreviated form as part of a Society for Ancient Mediterranean Religions panel on “Civil Strife and Ancient Mediterranean Religions,” at the annual meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature, Atlanta, Ga., November 22, 2010, and I am very grateful for the comments I received in this forum. -

Determining the Significance of Alliance Athologiesp in Bipolar Systems: a Case of the Peloponnesian War from 431-421 BCE

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2016 Determining the Significance of Alliance athologiesP in Bipolar Systems: A Case of the Peloponnesian War from 431-421 BCE Anthony Lee Meyer Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the International Relations Commons Repository Citation Meyer, Anthony Lee, "Determining the Significance of Alliance Pathologies in Bipolar Systems: A Case of the Peloponnesian War from 431-421 BCE" (2016). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 1509. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/1509 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DETERMINING THE SIGNIFICANCE OF ALLIANCE PATHOLOGIES IN BIPOLAR SYSTEMS: A CASE OF THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR FROM 431-421 BCE A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By ANTHONY LEE ISAAC MEYER Dual B.A., Russian Language & Literature, International Studies, Ohio State University, 2007 2016 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES ___April 29, 2016_________ I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Anthony Meyer ENTITLED Determining the Significance of Alliance Pathologies in Bipolar Systems: A Case of the Peloponnesian War from 431-421 BCE BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts. ____________________________ Liam Anderson, Ph.D. -

Pushing the Boundaries of Myth: Transformations of Ancient Border

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PUSHING THE BOUNDARIES OF MYTH: TRANSFORMATIONS OF ANCIENT BORDER WARS IN ARCHAIC AND CLASSICAL GREECE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CLASSICS: ANCIENT MEDITERRANEAN WORLD BY NATASHA BERSHADSKY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MARCH 2013 UMI Number: 3557392 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3557392 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 Acknowledgements I would like to express my deep gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee, Jonathan Hall, Christopher Faraone, Gloria Ferrari Pinney and Laura Slatkin, whose ideas and advice guided me throughout this research. Jonathan Hall’s energy and support were crucial in spurring the project toward completion. My identity as a classicist was formed under the influence of Gregory Nagy. I would like to thank him for the inspiration and encouragement he has given me throughout the years. Daniela Helbig’s assistance was invaluable at the finishing stage of the dissertation. I also thank my dear colleague-friends Anna Bonifazi, David Elmer, Valeria Segueenkova, Olga Levaniouk and Alexander Nikolaev for illuminating discussions, and Mira Bernstein, Jonah Friedman and Rita Lenane for their help. -

Nota Bene-- C:\NBWIN\DOCUMENT\TE916F~1

T E I R E S I A S Volume 35 (Part 1), 2005 ISSN 1206-5730 A Review and Bibliography of Boiotian Studies Compiled by A. Schachter ____________________________________________________________________________ Contents: Notice of Conference Work in Progress Adolfo J. Dominguez Jose Pascual Gonzalez Bibliography 1. Historical 2. Literary ______________________________________________________________________________ NOTICE OF CONFERENCE The Society of Boeotian Studies has announced that the 5th International Congress of Boeotian Studies in Greece will take place in Thebes, on 16-19 September of this year. Further information can be obtained from the Society, at 8-10 Z. Pigis Street, 3rd Floor, Athens 106, Greece. The e-mail address is: [email protected] ______________________________________________________________________________ WORK IN PROGRESS 051.0.01 Adolfo J. Dominguez of the Universidad Autonomia de Madrid sends the following report: RESEARCH PROJECT IN EPIKNEMIDIAN LOKRIS A research team of the Universidad Autonomia de Madrid, in collaboration with the 14th Ephoria of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities of Greece, has carried out a research project with the objective of developing a study of the historical topography of Epiknemidian Lokris, within a more extensive scheme which comprises diverse territories of Central Greece. The territory studied is bounded by Thermopylai on the northwest and Mount Knemis on the southeast, and lies between Mount Kallidromos and the northern end of the Gulf of Euboia. The literary sources do not say much about the history of this territory, and there is not even unanimity concerning the number of states within it. Epigraphy does not provide much useful information either, since there are not many inscriptions from the region. -

The Delphic Triangle

Vol. 5(9), pp. 267-274, October, 2013 International Journal of Library and Information DOI: 10.5897/IJLIS2012.045 ISSN 2141–2537 ©2013 Academic Journals Science http://www.academicjournals.org/IJLIS Full Length Research Paper The Delphi technique for library research Ravonne Green 1177 Lakeshore Circle Gainesville, GA 30501, USA. Accepted 5 June, 2013 The Delphi technique has been useful in educational settings in forming guidelines, standards, and in predicting trends. Scholars recommend many uses for the Delphi Technique in higher education. The Delphi Technique has not traditionally been applied in library settings. However, this technique could have the same uses and benefits in library settings as have been reported in other settings. The thorough Delphi researcher in an academic library setting seeks to reconcile the Delphi consensus with current literature, institutional research, and the campus environment. This triangle forms a sound base for responsible research practice. Key words: Educational settings, higher educational, library settings, INTRODUCTION “No man alive, however young and strong, with mortal at producing a detailed critical examination and discus- force alone could hope to budge that bed . for it sion. Delphi studies have been useful in educational contains a secret in its making. Within our court a long- settings in forming guidelines, standards, and in leaved olive tree stood stout and vigorous, just like a predicting trends. pillar. Around that trunk I built our bridal room. I finished Background it with close-set stones and laid a roof above; I added The most notable use of the Delphi technique was the doors that fitted faultlessly. Then I lopped off the olive’s RAND corporation study conducted by Norman Dalkey long-leaved limbs; and so I thinned the trunk. -

Greek Mysteries

GREEK MYSTERIES Mystery cults represent the spiritual attempts of the ancient Greeks to deal with their mortality. As these cults had to do with the individual’s inner self, privacy was paramount and was secured by an initiation ceremony, a personal ritual that estab- lished a close bond between the individual and the gods. Once initiated, the indi- vidual was liberated from the fear of death by sharing the eternal truth, known only to the immortals. Because of the oath of silence taken by the initiates, a thick veil of secrecy covers those cults and archaeology has become our main tool in deciphering their meaning. In a field where archaeological research constantly brings new data to light, this volume provides a close analysis of the most recent discoveries, as well as a critical re-evaluation of the older evidence. The book focuses not only on the major cults of Eleusis and Samothrace, but also on the lesser-known Mysteries in various parts of Greece, over a period of almost two thousand years, from the Late Bronze Age to the Roman Imperial period. In our mechanized and technology-oriented world, a book on Greek spirituality is both timely and appropriate. The authors’ inter-disciplinary approach extends beyond the archaeological evidence to cover the textual and iconographic sources and provides a better understanding of the history and rituals of those cults. Written by an international team of acknowledged experts, Greek Mysteries is an important contribution to our understanding of Greek religion and society. Michael B. Cosmopoulos is the Hellenic Government–Karakas Foundation Profes- sor of Greek Studies and Professor of Greek Archaeology at the University of Missouri-St. -

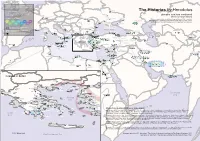

The Histories by Herodotus Chapter, a Hexagon with Light Border Is Drawn Near the Location the Character Hylaea Comes From

For each location mentioned in a chapter, a hexagon with dark border is drawn near that location. Dnieper For each character mentioned in a Gelonus The Histories by Herodotus chapter, a hexagon with light border is drawn near the location the character Hylaea comes from. placable locations mentioned Celts Danube Pyrene three or more times Chapter Color Scale: Gerrians Carpathian Mountains Tanaïs Where a region is dominated by a large settlement (like a capital), Far Scythia the settlement is generally used instead of the region to save space. I III V VII IX Some names in crowded locations on the map have been left out. Dacia Tyras Borysthenes II IV VI VIII Cremnoi Istros the place or the people was Illyria Scythian Neapolis mentioned explicitly Getae Marseille Odrysians Black Sea a character from nearby was Aléria Italy Mesambria Caucasus Massagetae Phasis mentioned Paeonia Sinop Pteria Caere Brygians Apollonia city or mountain location Mt. Haemus Caspian Byzantium Colchis Sea Sardinia Taranto Thyrea Sogdia Siris Velia Messapii Terme River Cyzicus Gordium Sybaris Crotone Cappadocia Sardis Armenia Messina Segesta Rhegium Greece Tigris Caspiane Tartessos Gela Pamphylia Parthia Carthage Selinunte Syracuse Milas Kaunos Cilicia Telmessos Nineveh Kamarina Lindos Posideion Xanthos Salamis Euphrates Kourion Ecbatana Amathus Gandhara Cyprus Tyre Sidon Cyrene Lotophagi Babylon Susa Barca Garamantes Macai Saïs Ienysos Heliopolis Petra Atlas Persepolis Asbystai Awjila Memphis Ammonians Egyptian Thebes Greece in detail Elephantine BC invasion b Myrkinos 480 y Xe rxes Red Macedonia Abdera Cicones Eïon Doriscus Sea Therma The Nile Olynthus Akanthos Thasos Cardia Sestos Pieria Vardar Samothrace Lampsacus Chalcidice Sane Imbros Abydos Pindus Mt. -

Delphi and Beyond: an Examination Into the Role of Oracular Centres Within Mainland Gr Ee Ce

Delphi and Beyond: An Examination into the Role of Oracular Centres Within Mainland Gr ee ce by Jamie Andrew Potte r A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts at the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand August 2010 ii Abstract The Delphic Oracle stands as one of the most prestigious sanctuaries in the Greek landscape and certainly as the most reputable oracular centre in the region. In contrast, few other oracular centres made even a slight mark on Greece’s long and illustrious history. This study considers not only the possible reasons behind Delphi’s spectacular rise to power, but also what the factors may have been that prevented other oracular sites from successfully challenging Delphi’s supremacy. The sites considered in this study are restricted to those found in mainland Greece: five oracles in Boiotia; four in Achaia; three each in Phokis and Laconia; two in Thessaly, Epirus and the Argolid and one each in Elis, Corinthia and Thrace. Based on archaeological and epigraphic evidence, supported through reference to literary sources, this study finds that there were four key factors in determining whether an oracular site’s reputation would spread beyond its local community: the oracle’s age, location, oracular deity and its method of consultation. As this study shows, in all these factors, Delphi had (or was promoted as having) a clear advantage. iii Preface The task of writing a thesis is both challenging and rewarding, and something that should not be attempted without the support of friends and colleagues. I would thus like to thank all those who have provided welcome assistance throughout this process. -

A Brief History of Ancient Greece: Politics, Society, and Culture

A Brief History of Ancient Greece: Politics, Society, and Culture Sarah B. Pomeroy, et al. OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS A BRIEF HISTORY OF ANCIENT GREECE This page intentionally left blank TITLE PAGE A BRIEF HISTORY OF ANCIENT GREECE Politics, Society, and Culture Sarah B. Pomeroy Stanley M. Burstein Hunter College and California State University, the City University of New York Los Angeles Graduate Center Walter Donlan Jennifer Tolbert Roberts University of City College and California, Irvine the City University of New York Graduate Center New York • Oxford OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 2004 Oxford University Press Oxford New York Auckland Bangkok Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi São Paulo Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Copyright © 2004 by Sarah B. Pomeroy, Stanley M. Burstein, Walter Donlan, and Jennifer Tolbert Roberts Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A brief history of ancient Greece : politics, society, and culture / by Sarah B. Pomeroy . [et al.]. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-19-515680-3 — ISBN 0-19-515681-1 (pbk.) 1. Greece—History—To 146 B.C. I. Pomeroy, Sarah B. DF214.B74 2004 938’.09—dc22 2003060873 Printing (last digit): 987654321 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper For Our Children and Grandchildren This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS List of Maps xi Acknowledgments xii Preface xiii Time Line xv Introduction 1 I Early Greece and the Bronze Age 12 Greece in the Stone Ages 12 Greece in the Early and Middle Bronze Ages (c. -

Rambles and Studies in Greece by J

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Rambles and Studies in Greece by J. P. Mahaffy This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Rambles and Studies in Greece Author: J. P. Mahaffy Release Date: February 16, 2011 [Ebook 35298] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK RAMBLES AND STUDIES IN GREECE*** RAMBLES IN GREECE The Acropolis, Athens RAMBLES AND STUDIES IN GREECE BY J. P. MAHAFFY KNIGHT OF THE ORDER OF THE SAVIOUR; AUTHOR OF “SOCIAL LIFE IN GREECE;”“A HISTORY OF GREEK LITERATURE;” “GREEK LIFE AND THOUGHT FROM THE DEATH OF ALEXANDER;” “THE GREEK WORLD UNDER ROMAN SWAY,” ETC. vi Rambles and Studies in Greece ILLUSTRATED PHILADELPHIA HENRY T. COATES & CO. 1900 HUNC LIBRUM Edmundo Wyatt Edgell OB INSIGNEM INTER CASTRA ITINERA OTIA NEGOTIA LITTERARUM AMOREM OLIM DEDICATUM NUNC CARISSIMI AMICI MEMORIAE CONSECRAT AUCTOR [vii] PREFACE. Few men there are who having once visited Greece do not contrive to visit it again. And yet when the returned traveller meets the ordinary friend who asks him where he has been, the next remark is generally, “Dear me! have you not been there before? How is it you are so fond of going to Greece?” There are even people who imagine a trip to America far more interesting, and who at all events look upon a trip to Spain as the same kind of thing—southern climate, bad food, dirty inns, and general discomfort, odious to bear, though pleasant to describe afterward in a comfortable English home. -

Ancient Greece from the Air" Slides 931 Slides

RAYMOND V. SCHODER, S.J. (1916-1987) Classical Studies Department "Ancient Greece from the Air" Slides 931 slides Ace. No. 89-15 Computer Name: SCHODER.GRE 7 Meta I Slide Boxes Location: I8C In August 1962, August 1967, and June of 1968 Fr. Raymond V. Schader, S.J., photographed ancient Greek archeological sites from the air. Most of these photographs were taken through the open door of a DC3 plane piloted by and belonging to the Hellenic Air Force. Of these photographs 140 were published in Wings over Hcllas: Ancient Greece from the Air by Raymond V. Schader, S.J. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1974). 1 In the introduction to his work Fr. Schader explains the procedures employed in taking these photographs and the aim which motivated him: to present all important excavated sites of ancient Greece, both mainland and islands and from Minoan to Roman times, from this advantageous point of view as a new aid to archeology and to historical studies as well as to visitors to the sites .... Only ancient sites are included, though many medieval centres are also meaningful from the air and I have photographed them also. The photographic slides taken by Fr. Schoder during this project make up the bulk of the collection of slides listed below. Although ancient ruins arc the predominant subject of the slides, there are several slides depicting contemporary cities from above. Interesting to note arc the first three slides showing the technique which Fr. Schader used to photograph from the air. The slides arc maintained numerically in the order in which they were transferred to the Archives.