Ponderreviewvol2iss1full.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Helena Mace Song List 2010S Adam Lambert – Mad World Adele – Don't You Remember Adele – Hiding My Heart Away Adele

Helena Mace Song List 2010s Adam Lambert – Mad World Adele – Don’t You Remember Adele – Hiding My Heart Away Adele – One And Only Adele – Set Fire To The Rain Adele- Skyfall Adele – Someone Like You Birdy – Skinny Love Bradley Cooper and Lady Gaga - Shallow Bruno Mars – Marry You Bruno Mars – Just The Way You Are Caro Emerald – That Man Charlene Soraia – Wherever You Will Go Christina Perri – Jar Of Hearts David Guetta – Titanium - acoustic version The Chicks – Travelling Soldier Emeli Sande – Next To Me Emeli Sande – Read All About It Part 3 Ella Henderson – Ghost Ella Henderson - Yours Gabrielle Aplin – The Power Of Love Idina Menzel - Let It Go Imelda May – Big Bad Handsome Man Imelda May – Tainted Love James Blunt – Goodbye My Lover John Legend – All Of Me Katy Perry – Firework Lady Gaga – Born This Way – acoustic version Lady Gaga – Edge of Glory – acoustic version Lily Allen – Somewhere Only We Know Paloma Faith – Never Tear Us Apart Paloma Faith – Upside Down Pink - Try Rihanna – Only Girl In The World Sam Smith – Stay With Me Sia – California Dreamin’ (Mamas and Papas) 2000s Alicia Keys – Empire State Of Mind Alexandra Burke - Hallelujah Adele – Make You Feel My Love Amy Winehouse – Love Is A Losing Game Amy Winehouse – Valerie Amy Winehouse – Will You Love Me Tomorrow Amy Winehouse – Back To Black Amy Winehouse – You Know I’m No Good Coldplay – Fix You Coldplay - Yellow Daughtry/Gaga – Poker Face Diana Krall – Just The Way You Are Diana Krall – Fly Me To The Moon Diana Krall – Cry Me A River DJ Sammy – Heaven – slow version Duffy -

The Uk's Top 200 Most Requested Songs in 2014

The Uk’s top 200 most requested songs in 2014 1 Killers Mr. Brightside 2 Kings Of Leon Sex On Fire 3 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 4 Pharrell Williams Happy 5 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 6 Robin Thicke Blurred Lines 7 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody 8 Daft Punk Get Lucky 9 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 10 Bryan Adams Summer Of '69 11 Maroon 5 MovesLike Jagger 12 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 13 Bruno Mars Marry You 14 Psy Gangam Style 15 ABBA Dancing Queen 16 Queen Don't Stop Me Now 17 Rihanna We Found Love 18 Foundations Build Me Up Buttercup 19 Dexys Midnight Runners Come On Eileen 20 LMFAO Sexy And I Know It 21 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 22 B-52's Love Shack 23 Beyonce Crazy In Love 24 Michael Jackson Billie Jean 25 LMFAO Party Rock Anthem 26 Amy Winehouse Valerie 27 Avicii Wake Me Up! 28 Katy Perry Firework 29 Arctic Monkeys I Bet You Look Good On The Dancefloor 30 John Travolta & Olivia Newton-John Grease Megamix 31 Guns N' Roses Sweet Child O' Mine 32 Kenny Loggins Footloose 33 Olly Murs Dance With Me Tonight 34 OutKast Hey Ya! 35 Beatles Twist And Shout 36 One Direction What Makes You Beautiful 37 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 38 Clean Bandit Rather Be 39 Proclaimers I'm Gonna Be (500 Miles) 40 Stevie Wonder Superstition 41 Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes (I've Had) The Time Of My Life 42 Swedish House Mafia Don't You Worry Child 43 House Of Pain Jump Around 44 Oasis Wonderwall 45 Wham! Wake Me Up Before You Go-go 46 Cyndi Lauper Girls Just Want To Have Fun 47 David Guetta Titanium 48 Village People Y.M.C.A. -

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou

y f !, 2.(T I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings MAYA ANGELOU Level 6 Retold by Jacqueline Kehl Series Editors: Andy Hopkins and Jocelyn Potter Contents page Introduction V Chapter 1 Growing Up Black 1 Chapter 2 The Store 2 Chapter 3 Life in Stamps 9 Chapter 4 M omma 13 Chapter 5 A New Family 19 Chapter 6 Mr. Freeman 27 Chapter 7 Return to Stamps 38 Chapter 8 Two Women 40 Chapter 9 Friends 49 Chapter 10 Graduation 58 Chapter 11 California 63 Chapter 12 Education 71 Chapter 13 A Vacation 75 Chapter 14 San Francisco 87 Chapter 15 Maturity 93 Activities 100 / Introduction In Stamps, the segregation was so complete that most Black children didn’t really; absolutely know what whites looked like. We knew only that they were different, to be feared, and in that fear was included the hostility of the powerless against the powerful, the poor against the rich, the worker against the employer; and the poorly dressed against the well dressed. This is Stamps, a small town in Arkansas, in the United States, in the 1930s. The population is almost evenly divided between black and white and totally divided by where and how they live. As Maya Angelou says, there is very little contact between the two races. Their houses are in different parts of town and they go to different schools, colleges, stores, and places of entertainment. When they travel, they sit in separate parts of buses and trains. After the American Civil War (1861—65), slavery was ended in the defeated Southern states, and many changes were made by the national government to give black people more rights. -

Abstract Birds, Children, and Lonely Men in Cars and The

ABSTRACT BIRDS, CHILDREN, AND LONELY MEN IN CARS AND THE SOUND OF WRONG by Justin Edwards My thesis is a collection of short stories. Much of the work is thematically centered around loneliness, mostly within the domestic household, and the lengths that people go to get out from under it. The stories are meant to be comic yet dark. Both the humor and the tension comes from the way in which the characters overreact to the point where either their reality changes a bit to allow it for it, or they are simply fooling themselves. Overall, I am trying to find the best possible way to describe something without actually describing it. I am working towards the peripheral, because I feel that readers believe it is better than what is out in front. BIRDS, CHILDREN, AND LONELY MEN IN CARS AND THE SOUND OF WRONG A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English by Justin Edwards Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2008 Advisor:__________________________ Margaret Luongo Reader: ___________________________ Brian Roley Reader:____________________________ Susan Kay Sloan Table of Contents Bailing ........................................................................1 Dating ........................................................................14 Rake Me Up Before You Go ....................................17 The Way to My Heart ................................................26 Leaving Together ................................................27 The End -

An Analysis of Twentieth-Century Flute Sonatas by Ikuma Dan, Hikaru

Flute Repertoire from Japan: An Analysis of Twentieth-Century Flute Sonatas by Ikuma Dan, Hikaru Hayashi, and Akira Tamba D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Daniel Ryan Gallagher, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2019 D.M.A. Document Committee: Professor Katherine Borst Jones, Advisor Dr. Arved Ashby Dr. Caroline Hartig Professor Karen Pierson 1 Copyrighted by Daniel Ryan Gallagher 2019 2 Abstract Despite the significant number of compositions by influential Japanese composers, Japanese flute repertoire remains largely unknown outside of Japan. Apart from standard unaccompanied works by Tōru Takemitsu and Kazuo Fukushima, other Japanese flute compositions have yet to establish a permanent place in the standard flute repertoire. The purpose of this document is to broaden awareness of Japanese flute compositions through the discussion, analysis, and evaluation of substantial flute sonatas by three important Japanese composers: Ikuma Dan (1924-2001), Hikaru Hayashi (1931- 2012), and Akira Tamba (b. 1932). A brief history of traditional Japanese flute music, a summary of Western influences in Japan’s musical development, and an overview of major Japanese flute compositions are included to provide historical and musical context for the composers and works in this document. Discussions on each composer’s background, flute works, and compositional style inform the following flute sonata analyses, which reveal the unique musical language and characteristics that qualify each work for inclusion in the standard flute repertoire. These analyses intend to increase awareness and performance of other Japanese flute compositions specifically and lesser- known repertoire generally. -

Crystal Reports Activex Designer

Quiz List—Reading Practice Page 1 Printed Wednesday, March 18, 2009 2:36:33PM School: Churchland Academy Elementary School Reading Practice Quizzes Quiz Word Number Lang. Title Author IL ATOS BL Points Count F/NF 9318 EN Ice Is...Whee! Greene, Carol LG 0.3 0.5 59 F 9340 EN Snow Joe Greene, Carol LG 0.3 0.5 59 F 36573 EN Big Egg Coxe, Molly LG 0.4 0.5 99 F 9306 EN Bugs! McKissack, Patricia C. LG 0.4 0.5 69 F 86010 EN Cat Traps Coxe, Molly LG 0.4 0.5 95 F 9329 EN Oh No, Otis! Frankel, Julie LG 0.4 0.5 97 F 9333 EN Pet for Pat, A Snow, Pegeen LG 0.4 0.5 71 F 9334 EN Please, Wind? Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 55 F 9336 EN Rain! Rain! Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 63 F 9338 EN Shine, Sun! Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 66 F 9353 EN Birthday Car, The Hillert, Margaret LG 0.5 0.5 171 F 9305 EN Bonk! Goes the Ball Stevens, Philippa LG 0.5 0.5 100 F 7255 EN Can You Play? Ziefert, Harriet LG 0.5 0.5 144 F 9314 EN Hi, Clouds Greene, Carol LG 0.5 0.5 58 F 9382 EN Little Runaway, The Hillert, Margaret LG 0.5 0.5 196 F 7282 EN Lucky Bear Phillips, Joan LG 0.5 0.5 150 F 31542 EN Mine's the Best Bonsall, Crosby LG 0.5 0.5 106 F 901618 EN Night Watch (SF Edition) Fear, Sharon LG 0.5 0.5 51 F 9349 EN Whisper Is Quiet, A Lunn, Carolyn LG 0.5 0.5 63 NF 74854 EN Cooking with the Cat Worth, Bonnie LG 0.6 0.5 135 F 42150 EN Don't Cut My Hair! Wilhelm, Hans LG 0.6 0.5 74 F 9018 EN Foot Book, The Seuss, Dr. -

Ecological Consequences Artificial Night Lighting

Rich Longcore ECOLOGY Advance praise for Ecological Consequences of Artificial Night Lighting E c Ecological Consequences “As a kid, I spent many a night under streetlamps looking for toads and bugs, or o l simply watching the bats. The two dozen experts who wrote this text still do. This o of isis aa definitive,definitive, readable,readable, comprehensivecomprehensive reviewreview ofof howhow artificialartificial nightnight lightinglighting affectsaffects g animals and plants. The reader learns about possible and definite effects of i animals and plants. The reader learns about possible and definite effects of c Artificial Night Lighting photopollution, illustrated with important examples of how to mitigate these effects a on species ranging from sea turtles to moths. Each section is introduced by a l delightful vignette that sends you rushing back to your own nighttime adventures, C be they chasing fireflies or grabbing frogs.” o n —JOHN M. MARZLUFF,, DenmanDenman ProfessorProfessor ofof SustainableSustainable ResourceResource Sciences,Sciences, s College of Forest Resources, University of Washington e q “This book is that rare phenomenon, one that provides us with a unique, relevant, and u seminal contribution to our knowledge, examining the physiological, behavioral, e n reproductive, community,community, and other ecological effectseffects of light pollution. It will c enhance our ability to mitigate this ominous envirenvironmentalonmental alteration thrthroughough mormoree e conscious and effective design of the built environment.” -

Venturing in the Slipstream

VENTURING IN THE SLIPSTREAM THE PLACES OF VAN MORRISON’S SONGWRITING Geoff Munns BA, MLitt, MEd (hons), PhD (University of New England) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Western Sydney University, October 2019. Statement of Authentication The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original except as acknowledged in the text. I hereby declare that I have not submitted this material, either in full or in part, for a degree at this or any other institution. .............................................................. Geoff Munns ii Abstract This thesis explores the use of place in Van Morrison’s songwriting. The central argument is that he employs place in many of his songs at lyrical and musical levels, and that this use of place as a poetic and aural device both defines and distinguishes his work. This argument is widely supported by Van Morrison scholars and critics. The main research question is: What are the ways that Van Morrison employs the concept of place to explore the wider themes of his writing across his career from 1965 onwards? This question was reached from a critical analysis of Van Morrison’s songs and recordings. A position was taken up in the study that the songwriter’s lyrics might be closely read and appreciated as song texts, and this reading could offer important insights into the scope of his life and work as a songwriter. The analysis is best described as an analytical and interpretive approach, involving a simultaneous reading and listening to each song and examining them as speech acts. -

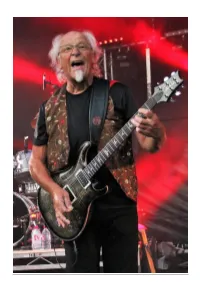

JETHRO TULL Aqualung

im Auftrag: medienAgentur Stefan Michel T 040-5149 1467 F 040-5149 1465 [email protected] JETHRO TULL Aqualung The 45th Anniversary Edition Repack Das vierte JETHRO TULL-Album in der überarbeiteten Jubiläumsedition auf 2 CDs/2DVDs mit zusätzlichen Songs, der EP Life Is A Long Song, einem Promo- Video von 1971 und allen Tracks in mehreren audiophilen Formaten! VÖ: 22. April! Ein geifernder alter Mann mit langen Haaren und in einem verdreckten Mantel steht an einer Straßenecke und sieht JETHRO TULL-Frontmann Ian Anderson erstaunlich ähnlich. Auf ihrem vierten Album bewiesen JETHRO TULL nicht nur einen kritischen Blick auf die Menschen, die Religion und andere fundamentale Themen, sie ließen mit dem legendären Cover durchaus auch ihren Sinn für Humor und Ironie durchblicken. Im März 1971 erschien Aqualung, eines der besten und legendärsten Alben der TULL, das sich über 7 Millionen Mal verkaufte und in Deutschland seinerzeit Platz 5 der Albumcharts erreichte. Neben dem Titelsong findet man auf dem Album auch die Single Hymn 43 und den Track Locomotive Breath, der zu den größten Erfolgen der Band zählt. Oftmals als „Konzeptalbum“ eingeschätzt (dem die Band selbst stets widersprach) bildete Aqualung den Übergang vom Song-orientierten Benefit zu den Prog-Rockigen Alben Thick as A Brick (1972) und A Passion Play (1973). Tatsächlich besitzen die Songs auf Aqualung einen thematischen Zusammenhang und weisen diverse interreferenzielle Bezüge auf. Es ist das erste Album mit Bassist Jeffrey Hammond und Keyboarder John Evan als festes Mitglied sowie das letzte JETHRO TULL- Album mit Drummer Clive Bunker. Produziert wurde es von Sänger und Flötist Ian Anderson und Terry Ellis. -

The Path of Lucius Park and Other Stories of John Valley

THE PATH OF LUCIUS PARK AND OTHER STORIES OF JOHN VALLEY By Elijah David Carnley Approved: Sybil Baker Thomas P. Balázs Professor of English Professor of English (Chair) (Committee Member) Rebecca Jones Professor of English (Committee Member) J. Scott Elwell A. Jerald Ainsworth Dean of College of Arts and Sciences Dean of the Graduate School THE PATH OF LUCIUS PARK AND OTHER STORIES OF JOHN VALLEY By Elijah David Carnley A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Master’s of English The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Chattanooga, Tennessee May 2013 ii Copyright © 2013 By Elijah David Carnley All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT This thesis comprises a writer’s craft introduction and nine short stories which form a short story cycle. The introduction addresses the issue of perspective in realist and magical realist fiction, with special emphasis on magical realism and belief. The stories are a mix of realism and magical realism, and are unified by characters and the fictional setting of John Valley, FL. iv DEDICATION These stories are dedicated to my wife Jeana, my parents Keith and Debra, and my brother Wesley, without whom I would not have been able to write this work, and to the towns that served as my home in childhood and young adulthood, without which I would not have been inspired to write this work. v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my Fiction professors, Sybil Baker and Tom Balázs, for their hard work and patience with me during the past two years. -

And Report 133.Pdf

AND 133 Report říjen 2019 Dnes jen telegraficky, abych hned stihl rozeslat tyto novinky a naladil Vás na netrpělivě očekávané koncerty Martina Barre dnes, zítra a pozítří v ČR. Takže si užijte čtení a večer i muziku! Na prvním místě tohoto čísla fanzinu britských skalních jethrologů Davida Reese a Martina Webba je omluva Ianu Andersonovi - v jakémsi rozhovoru Reese s Martinem Barrem vyjádřil tento bývalý kytarista Jethro Tull politování nad tím, že nedostává tantiémy za bonusovou skladbu A Winter Snowscape z posledního oficiálního tullího počinu The Christmas Album. Ukázalo se však, že zmíněný track je standardní albovou skladbou, a tudíž Martinovi příjmy z jejího prodeje normálně běží… Recenze nového „knižního“ formátu vydání remixovaného alba Stormwatch Remixovaný Stormwatch nakonec vychází téměř přesně po 40 letech od svého prvního vydání. Album tehdy představovalo konec jedné éry, a pro mnoho fanů dodnes znamenalo zánik klasických Jethro Tull. Pro jiné pak zase naopak představovaly změny v sestavě zajištění neuvěřitelné dlouhé životnosti kapely. Na disku 1 Steven Wilson jako vždy vdechl starší nahrávce nový život. Disk 2 uvádí ‘spřízněné nahrávky’ – a ty jsou pro mnoho posluchačů na těchto nových setech tím nejzajímavějším, jelikož dosud nebyly slyšeny. Přesněji řečeno, některé už vyšly (7 z 15), ale tady je máme všechny pěkně pohromadě na jednom CD. Zajímavý je Reesův názor, že toto CD nevydaných věcí by dobře obstálo i jako samostatné album! Objevuje se zde dlouho očekávaná skladba Davida (Dee) Palmera (-ové) s názvem Urban Apocalypse; existence této písně byla věrným fandům známa, a slyšet jsme ji mohli už na nedávném albu Dee Through Darkened Glass. Teď ji tady máme konečně jako původní nahrávku Jethro Tull.