Football Barriers – Aboriginal Under‐Representation and Disconnection from the ‘World Game’ John Maynard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official Media Guide of Australia at the 2014 Fifa World Cup Brazil 0

OFFICIAL MEDIA GUIDE OF AUSTRALIA AT THE 2014 FIFA WORLD CUP BRAZIL 0 Released: 14 May 2014 2014 FIFA WORLD CUP BRAZIL OFFICIAL MEDIA GUIDE OF AUSTRALIA TM AT THE 2014 FIFA WORLD CUP Version 1 CONTENTS Media information 2 2014 FIFA World Cup match schedule 4 Host cities 6 Brazil profile 7 2014 FIFA World Cup country profiles 8 Head-to-head 24 Australia’s 2014 FIFA World Cup path 26 Referees 30 Australia’s squad (preliminary) 31 Player profiles 32 Head coach profile 62 Australian staff 63 FIFA World Cup history 64 Australian national team history (and records) 66 2014 FIFA World Cup diary 100 Copyright Football Federation Australia 2014. All rights reserved. No portion of this product may be reproduced electronically, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of Football Federation Australia. OFFICIAL MEDIA GUIDE OF AUSTRALIA AT THE 2014 FIFA WORLD CUPTM A publication of Football Federation Australia Content and layout by Andrew Howe Publication designed to print two pages to a sheet OFFICIAL MEDIA GUIDE OF AUSTRALIA AT THE 2014 FIFA WORLD CUP BRAZIL 1 MEDIA INFORMATION AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL TEAM / 2014 FIFA WORLD CUP BRAZIL KEY DATES AEST 26 May Warm-up friendly: Australia v South Africa (Sydney) 19:30 local/AEST 6 June Warm-up friendly: Australia v Croatia (Salvador, Brazil) 7 June 12 June–13 July 2014 FIFA World Cup Brazil 13 June – 14 July 12 June 2014 FIFA World Cup Opening Ceremony Brazil -

Brisbane Magic Futsal Advisory Panel Les Murray AM

Brisbane Magic Futsal Advisory Panel Les Murray AM Brisbane Magic Futsal is extremely pleased to announce Australia's leading football identity, Mr Les Murray AM as a member our Advisory Panel. Mr Murray began work as a journalist in 1971, changing his name from his native Hungarian for commercial reasons. In between, he found time to perform as a singer in the Rubber Band musical group. He moved to Network Ten as a commentator in 1977, before moving to the multi-cultural network where he made a name for himself - SBS - in 1980. Mr Murray began at SBS as a subtitler in the Hungarian language, but soon turned to covering football. He has been the host for the SBS coverage of football including World Cups since 1986, as well as Australia's World Cup Qualifiers, most memorably in 1997 and 2005. He is a member of Football Federation Australia - Football Hall of Fame as recognition for his contributions to the sport. Mr Murray has been host to several sports programs for SBS over the year, which includes On the Ball (1984 - 2000), The World Game (2001 - present) and Toyota World Sports (1990 - 2006). On June 1, 2006, Murray published his autobiography, By the Balls. Murray was made a Member of the Order of Australia for his services to Association football on June 12, 2006 as part of the Queen's Birthday honours list. In 1996, Murray became SBS's Sports Director, and in 2006, stepped down. He has decided to become an editorial supervisor for SBS instead, while his on-air role remains the same. -

2018 Round 11 Wollongong Wolves FC VS Marconi Stallions FC

KICKOFF vs ® ROUND 11 WIN STADIUM 3PM SUNDAY 20TH MAY 2018 #NPLNSW CORPORATE PARTNERS 2 NPLNSW.COM.AU CONTENTS WOLLONGONG WOLVES COACHING STAFF & MANAGEMENT 1st Team Coach Jacob Timpano 1st Grade Assistant Coach Luke Wilkshire and Nick Montgomery Senior Manager Robert Positti Under 20s Manager Robert Positti Under 18s Coach Richard Lloyd GK Coach John Krajnovic Health and Medical Services Figtree Physiotherapy Match Preview 6 Technical Director Neil Mann Team Lineups 20 CEO Chris Papakosmas Season Draw 34 Admin Manager Susan Gatt Program Contributors Malcolm Rowney Photographer - Seniors Pedro Garcia Photographer – Juniors Chris Horn Ground Announcer Andrew Byron For advertising opportunities, please contact Susan Gatt on 02 42 722 624. This program is proudly printed by WOLVES SHOP 32 Waverley Drive Unanderra Public Notices: • Entry inside the perimeter fence of the playing area is prohibited at all times and offenders will be prosecuted. • All spectators are requested to vacate the ground within 15 minutes of the end of the final game. Police may be requested to remove any unauthorised people who remain after the stipulated time. • The setting alight of, or the lighting or discharging of any type of object, including fireworks, signal or smoke flares is strictly prohibited. Offenders will be arrested and charged. Website: wollongongwolves.com.au Email: [email protected] Phone: 02 42 722 624 Address: 32 Waverley Drive Unanderra NSW 2526 Twitter: @wollgongwolves Facebook: fb.com/wollongongwolves Instagram: @WollongongWolves 3 WELCOME #NPLNSW elcome everyone to our Round 11 match debut here at our home of football across Wagainst Marconi Stallions here at WIN the Illawarra and South Coast, in front of the Stadium – The Wolf Den. -

SBS to Farewell Football Analyst, Craig Foster, After 18 Years with the Network

24 June 2020 SBS to farewell football analyst, Craig Foster, after 18 years with the network SBS today announced that multi award-winning sports broadcaster, Craig Foster, will leave his permanent role at SBS as Chief Football Analyst at the end of July to pursue other challenges. SBS plans to continue working with Craig in the future on the network’s marquee football events. Craig will broadcast FIFA’s decision for hosting rights to the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup™ on Friday morning at 8am on SBS, alongside Lucy Zelić, as a fitting farewell to an 18-year career. Craig Foster said: “My deepest gratitude to SBS Chairpersons, Directors, management, colleagues and our loyal viewers across football and news for an incredible journey. SBS provided not just an opportunity, but a mission back in 2002 and I instantly knew that we were aligned in our values, love of football and vision for the game. But the organisational spirit of inclusion, acceptance of diversity and promotion of Australia’s multicultural heart struck me most deeply. We brought this to life through football, but the mission was always to create a better Australia and world. My own challenges lie in this field and I will miss the people, above all, though I will never be too far away. I will always be deeply proud of having called SBS home for so long and look forward to walking down memory lane and thanking everyone personally over the next month.” SBS Managing Director, James Taylor, said: “Craig is one of the finest football analysts and commentators, and has made a significant contribution to SBS over almost two decades. -

Aboriginal Agency, Institutionalisation and Survival

2q' t '9à ABORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND PEGGY BROCK B. A. (Hons) Universit¡r of Adelaide Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History/Geography, University of Adelaide March f99f ll TAT}LE OF CONTENTS ii LIST OF TAE}LES AND MAPS iii SUMMARY iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . vii ABBREVIATIONS ix C}IAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION I CFIAPTER TWO. TI{E HISTORICAL CONTEXT IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA 32 CHAPTER THREE. POONINDIE: HOME AWAY FROM COUNTRY 46 POONINDIE: AN trSTä,TILISHED COMMUNITY AND ITS DESTRUCTION 83 KOONIBBA: REFUGE FOR TI{E PEOPLE OF THE VI/EST COAST r22 CFIAPTER SIX. KOONIBBA: INSTITUTIONAL UPHtrAVAL AND ADJUSTMENT t70 C}IAPTER SEVEN. DISPERSAL OF KOONIBBA PEOPLE AND THE END OF TI{E MISSION ERA T98 CTIAPTER EIGHT. SURVTVAL WITHOUT INSTITUTIONALISATION236 C}IAPTER NINtr. NEPABUNNA: THtr MISSION FACTOR 268 CFIAPTER TEN. AE}ORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND SURVTVAL 299 BIBLIOGRAPI{Y 320 ltt TABLES AND MAPS Table I L7 Table 2 128 Poonindie location map opposite 54 Poonindie land tenure map f 876 opposite 114 Poonindie land tenure map f 896 opposite r14 Koonibba location map opposite L27 Location of Adnyamathanha campsites in relation to pastoral station homesteads opposite 252 Map of North Flinders Ranges I93O opposite 269 lv SUMMARY The institutionalisation of Aborigines on missions and government stations has dominated Aboriginal-non-Aboriginal relations. Institutionalisation of Aborigines, under the guise of assimilation and protection policies, was only abandoned in.the lg7Os. It is therefore important to understand the implications of these policies for Aborigines and Australian society in general. I investigate the affect of institutionalisation on Aborigines, questioning the assumption tl.at they were passive victims forced onto missions and government stations and kept there as virtual prisoners. -

Did You Know? Some Quick Statistics…

Football, or soccer, is truly a World Game, with an unmatched ability to bring people from different backgrounds together. With attention turning to Brazil for the FIFA World Cup, which starts on 12 June 2014, there is no better time to discover the contributions Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have made to the World Game. Did you know? Harry Williams is the only male Aboriginal player to represent Australia at a World Cup. He joined the Socceroos in 1970 and later played in the 1974 World Cup in Germany.1 In 2008, Jade North became the first Aboriginal player to captain the Socceroos. He has a tattoo with his tribal name, “Biripi”, on his left arm and recently played in the 2014 A-league grand final.2 Lydia Williams and Kyah Simon are the first two Aboriginal women to play together in a World Cup. Lydia played in the 2007 and 2011 World Cups, and Kyah played in 2011.3 In 2011 Kyah became the first Aboriginal Australian to score a goal in a World Cup. Charlie Perkins was offered a contract to play soccer for Manchester United before becoming the first Aboriginal person to graduate from the University of Sydney. Travis Dodd was the first Aboriginal Australian to score a goal for the Socceroos.4 Some quick statistics… The Football Federation of Australia (FFA) estimates that there are 2,600 registered Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander soccer players.5 Harry Williams played 6 matches for Australia in the 1974 World Cup qualifying campaign.6 1 http://www.deadlyvibe.com.au/2007/11/harry-williams/ 2 The Aboriginal Soccer Tribe: A History of Aboriginal Involvement with the World Game, John Maynard, Magabala Books: Broome, 2011 3 http://noapologiesrequired.com/the-matildas/15-facts-about-the-matildas 4 http://www.footballaustralia.com.au/perthglory/players/Travis-Dodd/72 5 http://www.footballaustralia.com.au/site/_content/document/00000601-source.pdf 6 Tatz, C & Tatz, C. -

My Mother Found Me in Alice Springs

THE FIRST ABORIGINAL DOCTOR Gordon Briscoe 19 April 2019 Born in Alice Springs in 1938 Gordon Briscoe was a talented soccer player and became the first Indigenous person to gain a PhD (Doctor of Philosophy) from an Australian University in 1997. Gordon Briscoe in the 1960s. Doctor Briscoe’s journey is remarkable. Since the 1950s he has been a prominent Indigenous activist, leader, researcher, writer, teacher and public commentator. After a challenging institutional upbringing which saw him criss-cross the nation, initially struggling at school with limited support, he managed to gain the highest qualification an Australian University can offer. Along the way he was the first Indigenous person to stand for Federal Parliament in 1972 and worked with legendary eye surgeon Fred Hollows to establish the National Trachoma and Eye Health Program. Today he is one of the leading academics specialising in Indigenous history and his research has helped him to reclaim his traditional family and sense of cultural identity. Descended from the Marduntjara and Pitjantjatjara peoples of Central Australia Briscoe’s maternal grandmother, Kanaki, was born west of Kulkara. She travelled around the Mardu lands to forage and participate in ceremonies. Kanaki’s traditional husband was Wati Kunmanara, but she conceived Briscoe’s mother Eileen with a white man named Billy Briscoe. Briscoe lived at “The Bungalow” in Alice Springs until he was four. After the bombing of Darwin in February 1942, the residents of the Aboriginal institutions were evacuated from the Northern Territory. Briscoe and his mother were initially evacuated to Mulgoa in the Blue Mountains of NSW, but after the birth of his brother they were sent to the South Australian town of Balaklava for the remainder of the war. -

2017 Round 07 Wollongong Wolves V Hakoah Sydney

KICKOFF ROUND 7 SUNDAY WIN STADIUM V 23RD APRIL 2017 FIXTURES TEAM LISTS FIRST GRADE MATCH PREVIEW 3PM TEAM OF THE WEEK #PS4NPLNSW CORPORATE PARTNERS 2 CONTENTSHEADING NPLNSW.COM.AU WOLLONGONG WOLVES COACHING STAFF & MANAGEMENT 1st Team Coach Jacob Timpano 1st Grade Assistant Coach Neil Mann and Alfredo Esteves Senior Managers Robert Positti and Surit Wadhwa Under 20s Coach Julio Miranda Under 18s Coach Richard Lloyd GK Coach John Krajnovic Match Preview 6 Health and Medical Services Figtree Physiotherapy Technical Director Neil Mann Team Lineups 18 CEO Chris Papakosmas 2017 Ladder 19 Admin Manager Susan Gatt Season Draw 30 Program Contributors Malcolm Rowney Photographer - Seniors Pedro Garcia Photographer – Juniors Chris Horn Ground Announcer Kevin Morrissey For advertising opportunities, please contact This program is proudly Susan Gatt on 4225 0999. printed by WOLVES SHOP 105 Crown Street Wollongong Public Notices: • Entry inside the perimeter fence of the playing area is prohibited at all times and offenders will be prosecuted. • All spectators are requested to vacate the ground within 15 minutes of the end of the final game. Police may be requested to remove any unauthorised people who remain after the stipulated time. • The setting alight of, or the lighting or discharging of any type of object, including fireworks, signal or smoke flares is strictly prohibited. Offenders will be arrested and charged. Website: wollongongwolves.com.au Email: [email protected] Phone: +61 2 4225 0999 Phone: 105 Crown St Wollongong NSW 2500 Twitter: @wollgongwolves Facebook: fb.com/wollongongwolves Instagram: @WollongongWolves 3 SPONSORS #PS4NPLNSW 4 WELCOME NPLNSW.COM.AU FROM THE he hunt continues, today, here at WIN Stadium Community Engagement Programs to cover as T– The Wolf Den as our Wolves take on Hakoah much territory as we can and introduce football to in a must win game for both sides. -

Football Federation Australia

Football (Soccer): Football Federation Australia “I’d argue with kids at school and they all were convinced that rugby league was the most popular world sport. That shows how isolated Australia was. Soccer had to be introduced by migrants. We’ve come a long way.”1 Brazilian Ambassador once wondered whether Australians had a linguistic or an anatomical problem, since they seemed to reserve the term ‘football’ for games in Awhich the players predominantly use their hands.2 Such is the seeming contradiction in Australia where the term for the game played with the feet is called soccer and football (which is rugby league, rugby union or Aussie rules depending on where you live) is played mostly with the hands. Football is no longer the poor cousin of the ‘big four’ national sports in Australia – cricket, rugby league, Australian rules football and rugby union. Following the 2006 FIFA World Cup, the game has finally come of age in Australia and is starting to seriously challenge the other sports for spectator, sponsor and media support. Tracing football’s roots Playing a ball game using the feet has been happening for thousands of years. Early history reveals at least half a dozen different games, varying to different degrees, which are related to the modern game of football. The earliest form of the game for which there is reliable evidence dates back to the 2nd and 3rd centuries B.C. in China. Another form of the game, also originating in the Far East, was the Japanese Kemari, which dates from about 500 to 600 years later and is still played today.3 However, it is almost certain that the development of the modern game took place in England and Scotland. -

2010 FIFA World Cup South Africa™ Teams

2010 FIFA World Cup South Africa™ Teams Statistical Kit 1 (To be used in conjunction with Match Kit) Last update: 5 June 2010 Next update: 10 June 2010 Contents Participants 2010 FIFA World Cup South Africa™..........................................................................................3 Global statistical overview: 32 teams at a glance..........................................................................................4 Algeria (ALG) ...................................................................................................................................................4 Argentina (ARG) ..............................................................................................................................................8 Australia (AUS)...............................................................................................................................................12 Brazil (BRA) ....................................................................................................................................................16 Cameroon (CMR)...........................................................................................................................................20 Chile (CHI) .....................................................................................................................................................23 Côte d’Ivoire (CIV)..........................................................................................................................................26 -

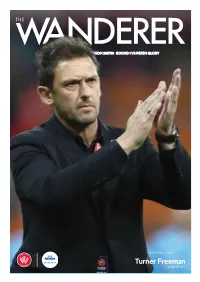

This Match We've Packed This Issue of the Wanderer with Everything You Need for Tonight's Match

SEVENTY-SECOND EDITION | SEASON 2017/18 | ROUND 1 VS PERTH GLORY Proudly brought to you by CONTENTS THIS MATCH WE'VE PACKED THIS ISSUE OF THE WANDERER WITH EVERYTHING YOU NEED FOR TONIGHT'S MATCH FEATURES SEVENTY-SECOND EDITION | SEASON 2017/18 | ROUND 1 VS PERTH GLORY Proudly brought to you by THE WANDERER The views in this publication are AN ODE TO POPA 8 WANDERERS TAKE RISDON BACK IN THE not necessarily the views of the The only leader the OUT NPL HONORS 14 GREEN & GOLD 20 NRMA Insurance Western Sydney Wanderers have ever known It was a season to remember From Perth to Western Wanderers FC. Material in this has said goodbye but his for the Red & Black’s U20s Sydney to Russia? publication is copyrighted and may legacy will live on still. and U18s sides. only be reproduced with the written permission from the Club. ADVERTISING REGULAR COLUMNS For all advertising enquiries for The Wanderer or partnership with the OPEN LETTER 5 TODAY’S MATCH 16 IN THE COMMUNITY 27 club please contact the Corporate Partnerships Team by sending an email WARM UP 6 JUNIOR WANDERER ZONE 18 CORPORATE NEWS 28 to [email protected] FIVE THINGS 11 FOX FOOTBALL FIX 22 OUR PARTNERS 29 PHOTOGRAPHY All photography in The Wanderer is PLAYERS TO WATCH TAKE FIVE courtesy of Ali Erhan, Getty Images Brought to you by Turner and Freeman 13 Brought to you by Turner and Freeman 25 and Steve Christo. 2 THE WANDERER ROUND 1 Refrigerator MR-WX743 Big Enough to Feed the Red and Black Army this Season! Mitsubishi Electric proudly supporting Western Sydney Wanderers FC. -

Preston Lions 2 Richmond 21 7 3 11 28 30 24 (J Dolevski 2)

Australia’s Favourite Football Fanzine And Even Bigger In Vermont! www.goalweekly.com $4 A-LEAGUE OPENING DAY BONANZA ISSUE Season 5: Issue 22 Monday 10th August 2009 PLAYER PROFILE ON VICTORY’S MATT THEODORE UP... UP... Photo: Brett McDonald AND AWAY! A-LEAGUE TAKES FLIGHT FOR VERSION V SIR BOB / SOUVENIR VICTORY POSTER / VPL RD 21 ANDREW COOK SEAFORD UNITED FC FULL NAME: Andrew Peter Cook BIRTHPLACE: Ipswich, England BIRTH DATE: 26th May 1982 HEIGHT: 181cm WEIGHT: 81kg MARRIED: No CAR: Toyota Corolla OCCUPATION OUTSIDE OF FOOTBALL: Sys- tems Accountant NICKNAME: Cookie PREVIOUS CLUBS: Stonham Athletic (UK) REPRESENTATIVE HONOURS: None CHILDHOOD FOOTBALL HERO: John Wark FAVOURITE O/S PLAYER: David Beckham FAVOURITE VPL PLAYER: None FAVOURITE FORMER SOCCEROO: None FAVOURITE CURRENT SOCCEROO: Mark Schwarzer MOST MEMORABLE MATCH AS A PLAYER: Playing in a blizzard against my best mate’s team back in England and netting an equal- iser in the last minute after we were rubbish all game! MOST MEMORABLE MATCH AS A FAN: Ipswich Town’s 4-2 play-off fi nal win against Barnsley in 2000 to take us into the Premier League, best day of my life. MOST MEMORABLE GOAL YOU’VE SCORED: A golden goal winner in the third position playoff at a Futsal tournament in Norway against a much fancied Spanish side in 2001. EARLIEST FOOTBALL MEMORY: Standing on the terraces at Portman Rd with my dad FUNNIEST MOMENT IN FOOTBALL: It was quite funny seeing Norwich City go down this year. BIGGEST DISAPPOINTMENT: Relegation in my fi rst season at Seaford. WORST INJURY: Touch wood, I have been very lucky with injuries.