The Tiberius Torture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Listening to Movies: Film Music and the American Composer Charles Elliston Long Middle School INTRODUCTION I Entered College

Listening to Movies: Film Music and the American Composer Charles Elliston Long Middle School INTRODUCTION I entered college a naïve 18-year-old musician. I had played guitar for roughly four years and was determined to be the next great Texas blues guitarist. However, I was now in college and taking the standard freshman music literature class. Up to this point the most I knew about music other than rock or blues was that Beethoven was deaf, Mozart composed as a child, and Chopin wrote a really cool piano sonata in B-flat minor. So, we’re sitting in class learning about Berlioz, and all of the sudden it occurred to me: are there any composers still working today? So I risked looking silly and raised my hand to ask my professor if there were composers that were still working today. His response was, “Of course!” In discussing modern composers, the one medium that continuously came up in my literature class was that of film music. It occurred to me then that I knew a lot of modern orchestral music, even though I didn’t really know it. From the time when I was a little kid, I knew the name of John Williams. Some of my earliest memories involved seeing such movies as E.T., Raiders of the Lost Ark, and The Empire Strikes Back. My father was a musician, so I always noted the music credit in the opening credits. All of those films had the same composer, John Williams. Of course, I was only eight years old at the time, so in my mind I thought that John Williams wrote all the music for the movies. -

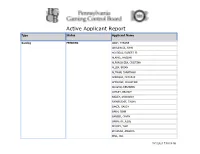

Active Applicant Report Type Status Applicant Name

Active Applicant Report Type Status Applicant Name Gaming PENDING ABAH, TYRONE ABULENCIA, JOHN AGUDELO, ROBERT JR ALAMRI, HASSAN ALFONSO-ZEA, CRISTINA ALLEN, BRIAN ALTMAN, JONATHAN AMBROSE, DEZARAE AMOROSE, CHRISTINE ARROYO, BENJAMIN ASHLEY, BRANDY BAILEY, SHANAKAY BAINBRIDGE, TASHA BAKER, GAUDY BANH, JOHN BARBER, GAVIN BARRETO, JESSE BECKEY, TORI BEHANNA, AMANDA BELL, JILL 10/1/2021 7:00:09 AM Gaming PENDING BENEDICT, FREDRIC BERNSTEIN, KENNETH BIELAK, BETHANY BIRON, WILLIAM BOHANNON, JOSEPH BOLLEN, JUSTIN BORDEWICZ, TIMOTHY BRADDOCK, ALEX BRADLEY, BRANDON BRATETICH, JASON BRATTON, TERENCE BRAUNING, RICK BREEN, MICHELLE BRIGNONI, KARLI BROOKS, KRISTIAN BROWN, LANCE BROZEK, MICHAEL BRUNN, STEVEN BUCHANAN, DARRELL BUCKLEY, FRANCIS BUCKNER, DARLENE BURNHAM, CHAD BUTLER, MALKAI 10/1/2021 7:00:09 AM Gaming PENDING BYRD, AARON CABONILAS, ANGELINA CADE, ROBERT JR CAMPBELL, TAPAENGA CANO, LUIS CARABALLO, EMELISA CARDILLO, THOMAS CARLIN, LUKE CARRILLO OLIVA, GERBERTH CEDENO, ALBERTO CENTAURI, RANDALL CHAPMAN, ERIC CHARLES, PHILIP CHARLTON, MALIK CHOATE, JAMES CHURCH, CHRISTOPHER CLARKE, CLAUDIO CLOWNEY, RAMEAN COLLINS, ARMONI CONKLIN, BARRY CONKLIN, QIANG CONNELL, SHAUN COPELAND, DAVID 10/1/2021 7:00:09 AM Gaming PENDING COPSEY, RAYMOND CORREA, FAUSTINO JR COURSEY, MIAJA COX, ANTHONIE CROMWELL, GRETA CUAJUNO, GABRIEL CULLOM, JOANNA CUTHBERT, JENNIFER CYRIL, TWINKLE DALY, CADEJAH DASILVA, DENNIS DAUBERT, CANDACE DAVIES, JOEL JR DAVILA, KHADIJAH DAVIS, ROBERT DEES, I-QURAN DELPRETE, PAUL DENNIS, BRENDA DEPALMA, ANGELINA DERK, ERIC DEVER, BARBARA -

Packet 12 (1).Pdf

The 2018 Scottie Written and edited by current and former players and coaches including Todd Garrison, Tyler Reid, Olivia Kiser, Anish Patel, Rajeev Nair, Garrison Page, Mason Reid, Parker Bannister, Daniel Dill. Packet Twelve TOSSUPS 1. This mountain has two summits, of which the South summit is approximately 1100 feet higher. The Kahiltna Glacier comes off the southwest side of this mountain, which is named after a Koyukon word meaning ‘high’ or ‘tall’. It was renamed in the lead up to the (*) 1896 presidential election, and retained that name until 2015. For 10 points, name this mountain, which was named Mount McKinley for 119 years before having its original name restored. (OK) ANSWER: Denali [accept Mount McKinley before mention] 2. One work by this non-Ovid poet that was written under the patronage of Maecenas is about the running of a farm and devotes an entire book to bees. Another work by this poet largely consists of pastoral themes, and is sometimes considered to include a reference to Jesus. This author’s most famous work traces the journey of a (*) Trojan warrior to Italy via Carthage. For 10 points, name this Roman poet of the Georgics, the Eclogues, and The Aeneid. (OK) ANSWER: Virgil [ or Publius Vergilius Maro] 3. One event taking place on this holiday is a drawing of lots where one goat is sacrificed and another is sent “to Azazel.” On the day before it, some practitioners swing a chicken over a person’s head in the kapparot ritual. This holiday ends with a long blast of the shofar in the Ne’ila prayer, and during it five (*) prohibitions are observed. -

SM a R T M U S E U M O F a R T U N Iv E R S It Y O F C H IC a G O B U L L E T in 2 0 0 6 – 20

http://smartmuseum.uchicago.edu Chicago, Illinois 60637 5550 South Greenwood Avenue SMART SMART M U S EUM OF A RT UN I VER SI TY OFCH ICAG O RT RT A OF EUM S U M SMART 2008 – 2006 N I ET BULL O ICAG H C OF TY SI VER I N U SMART MUSEUM OF ART UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO BULLETIN 2006– 2008 SMART MUSEUM OF ART UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO BULLETIN 2006–2008 MissiON STATEMENT / 1 SMART MUSEUM BOARD OF GOVERNORS / 3 REPORTS FROM THE CHAIRMAN AND DiRECTOR / 4 ACQUisiTIOns / 10 LOANS / 34 EXHIBITIOns / 44 EDUCATION PROGRAMS / 68 SOURCES OF SUPPORT / 88 SMART STAFF / 108 STATEMENT OF OPERATIOns / 112 MissiON STATEMENT As the ar t museum of the Universit y of Chicago, the David and Alfred Smar t Museum of Ar t promotes the understanding of the visual arts and their importance to cultural and intellectual history through direct experiences with original works of art and through an interdisciplinary approach to its collections, exhibitions, publications, and programs. These activities support life-long learning among a range of audiences including the University and the broader community. SMART MUSEUM BOARD OF GOVERNORS Robert Feitler, Chair Lorna C. Ferguson, Vice Chair Elizabeth Helsinger, Vice Chair Richard Gray, Chairman Emeritus Marilynn B. Alsdorf Isaac Goldman Larry Norman* Mrs. Edwin A. Bergman Jack Halpern Brien O’Brien Russell Bowman Neil Harris Brenda Shapiro* Gay-Young Cho Mary J. Harvey* Raymond Smart Susan O’Connor Davis Anthony Hirschel* Joel M. Snyder Robert G. Donnelley Randy L. Holgate John N. Stern Richard Elden William M. Landes Isabel C. -

THE MADNESS of the EMPEROR CALIGULA (Gaius Julius Caesar Germanicus) by A

THE MADNESS OF THE EMPEROR CALIGULA (Gaius Julius Caesar Germanicus) by A. T. SANDISON, B.Sc., M.D. Department of Pathology, the University and Western Infirmaty, Glasgow THROUGHOUT the centuries the name of Caligula has been synonymous with madness and infamy, sadism and perversion. It has been said that Marshal Gilles de Rais, perhaps the most notorious sadist of all time, modelled his behaviour. on that of the evil Caesars described by Suetonius, among whom is numbered Caligula. Of recent years, however, Caligula has acquired his apologists, e.g. Willrich; so also, with more reason, has the Emperor Tiberius, whose reputation has been largely rehabilitated by modern scholarship. Our knowledge of the life of Caligula depends largely on Suetonius, whose work D)e vita Caesarum was not published, until some eighty years after the death of Caligula in A.D. 41. Unfortunately that part ofTacitus's Annals which treated of the reign. of Caligula has been lost. Other ancient sources are Dio Cassius, whose History of Rome was written in the early third century and, to a lesser extent, Josephus, whose Anht itates Judaicac was published in A.D. 93, and Philo Jqdaeus, whose pamphlet Legatio ad- Gaium and In Flaccum may be considered as contemporary writings. It seems probable that all these ancient sour¢es are to some extent prejudiced and highly coloured. Suetonius's Gaius Caligula in De vita Caesarum is full of scabrous and sometimes entertaining stories, on some ofwhich little reliability can be plat-ed. Nevertheless, the outlines of Caligula's life-history are not in doubt, and a usefiul summary is given by Balsdon (i949) in the Oxford-Classical Dictionary. -

Vespasian's Apotheosis

VESPASIAN’S APOTHEOSIS Andrew B. Gallia* In the study of the divinization of Roman emperors, a great deal depends upon the sequence of events. According to the model of consecratio proposed by Bickermann, apotheosis was supposed to be accomplished during the deceased emperor’s public funeral, after which the senate acknowledged what had transpired by decreeing appropriate honours for the new divus.1 Contradictory evidence has turned up in the Fasti Ostienses, however, which seem to indicate that both Marciana and Faustina were declared divae before their funerals took place.2 This suggests a shift * Published in The Classical Quarterly 69.1 (2019). 1 E. Bickermann, ‘Die römische Kaiserapotheosie’, in A. Wlosok (ed.), Römischer Kaiserkult (Darmstadt, 1978), 82-121, at 100-106 (= Archiv für ReligionswissenschaftW 27 [1929], 1-31, at 15-19); id., ‘Consecratio’, in W. den Boer (ed.), Le culte des souverains dans l’empire romain. Entretiens Hardt 19 (Geneva, 1973), 1-37, at 13-25. 2 L. Vidman, Fasti Ostienses (Prague, 19822), 48 J 39-43: IIII k. Septembr. | [Marciana Aug]usta excessit divaq(ue) cognominata. | [Eodem die Mati]dia Augusta cognominata. III | [non. Sept. Marc]iana Augusta funere censorio | [elata est.], 49 O 11-14: X[— k. Nov. Fausti]na Aug[usta excessit eodemq(ue) die a] | senatu diva app[ellata et s(enatus) c(onsultum) fact]um fun[ere censorio eam efferendam.] | Ludi et circenses [delati sunt. — i]dus N[ov. Faustina Augusta funere] | censorio elata e[st]. Against this interpretation of the Marciana fragment (as published by A. Degrassi, Inscr. It. 13.1 [1947], 201) see E. -

Tiberius Nero Caesar (Tiberius) - the Lives of the Twelve Caesars, Volume 3

Tiberius Nero Caesar (Tiberius) - The Lives Of The Twelve Caesars, Volume 3. C. Suetonius Tranquillus Project Gutenberg's Tiberius Nero Caesar (Tiberius), by C. Suetonius Tranquillus This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Tiberius Nero Caesar (Tiberius) The Lives Of The Twelve Caesars, Volume 3. Author: C. Suetonius Tranquillus Release Date: December 13, 2004 [EBook #6388] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TIBERIUS NERO CAESAR *** Produced by Tapio Riikonen and David Widger THE LIVES OF THE TWELVE CAESARS By C. Suetonius Tranquillus; To which are added, HIS LIVES OF THE GRAMMARIANS, RHETORICIANS, AND POETS. The Translation of Alexander Thomson, M.D. revised and corrected by T.Forester, Esq., A.M. Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. TIBERIUS NERO CAESAR. (192) I. The patrician family of the Claudii (for there was a plebeian family of the same name, no way inferior to the other either in power or dignity) came originally from Regilli, a town of the Sabines. They removed thence to Rome soon after the building of the city, with a great body of their dependants, under Titus Tatius, who reigned jointly with Romulus in the kingdom; or, perhaps, what is related upon better authority, under Atta Claudius, the head of the family, who was admitted by the senate into the patrician order six years after the expulsion of the Tarquins. -

Portrait N Augustus Tiberius Caligula Claudius Name B September BC

Portrait Name Born Reigned Succession Died Became de January facto emperor as a Augustus September 23 63 16 27 BC – result of the 'first August 19, 14 AD CAESAR DIVI FILIVS AVGVSTVS BC, Nola, Italia August 19, settlement' between Natural causes. 14 AD himself and the Roman Senate. Son of Augustus's September March 16, 37 AD wife Livia by a November 16 42 18, 14 AD – Probably old age, Tiberius previous marriage; TIBERIVS CAESAR AVGVSTVS BC, Rome March 16, 37 possibly adopted son AD assassinated ofAugustus. January 24, 41 AD Assassinated in a March 18, 37 Caligula August 31, 12 Son of Tiberius's conspiracy GAIVS CAESAR AVGVSTVS AD – January AD,Antium, Italia nephew Germanicus. involving senators GERMANICVS 24, 41 AD and Praetorian Guards. Nephew of Tiberius, October 13, 54 AD brother January Probably poisoned August 1, 10 ofGermanicus and Claudius 25/26, 41 AD by his TIBERIVS CLAVDIVS CAESAR BC,Lugdunum, Gallia uncle of Caligula; – October 13, wife Agrippina the AVGVSTVS GERMANICVS Lugdunensis proclaimed emperor 54 AD Younger, in favour by the Praetorian of her son Nero. Guard. June 11, 68 AD Grandson October 13, Committed suicide Nero December 15, 37 of Germanicus, step- NERO CLAVDIVS CAESAR 54 AD – June after being declared AD, Antiuum, Italia and adopted son AVGVSTVS GERMANICVS 11, 68 AD a public enemy by of Claudius. the Senate. Portrait Name Born Reigned Succession Died Seized power June 8, 68 after Nero's January 15, 69 AD Galba December 24 3 BC, AD – SERVIVS GALBA IMPERATOR suicide, with Murdered Near Terracina,Italia January CAESAR -

Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation Within American Tap Dance Performances of The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Brynn Wein Shiovitz 2016 © Copyright by Brynn Wein Shiovitz 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950 by Brynn Wein Shiovitz Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Susan Leigh Foster, Chair Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950, looks at the many forms of masking at play in three pivotal, yet untheorized, tap dance performances of the twentieth century in order to expose how minstrelsy operates through various forms of masking. The three performances that I examine are: George M. Cohan’s production of Little Johnny ii Jones (1904), Eleanor Powell’s “Tribute to Bill Robinson” in Honolulu (1939), and Terry- Toons’ cartoon, “The Dancing Shoes” (1949). These performances share an obvious move away from the use of blackface makeup within a minstrel context, and a move towards the masked enjoyment in “black culture” as it contributes to the development of a uniquely American form of entertainment. In bringing these three disparate performances into dialogue I illuminate the many ways in which American entertainment has been built upon an Africanist aesthetic at the same time it has generally disparaged the black body. -

Magic and the Roman Emperors

1 MAGIC AND THE ROMAN EMPERORS (1 Volume) Submitted by Georgios Andrikopoulos, to the University of Exeter as a thesis/dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classics, July 2009. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. ..................................... (signature) 2 Abstract Roman emperors, the details of their lives and reigns, their triumphs and failures and their representation in our sources are all subjects which have never failed to attract scholarly attention. Therefore, in view of the resurgence of scholarly interest in ancient magic in the last few decades, it is curious that there is to date no comprehensive treatment of the subject of the frequent connection of many Roman emperors with magicians and magical practices in ancient literature. The aim of the present study is to explore the association of Roman emperors with magic and magicians, as presented in our sources. This study explores the twofold nature of this association, namely whether certain emperors are represented as magicians themselves and employers of magicians or whether they are represented as victims and persecutors of magic; furthermore, it attempts to explore the implications of such associations in respect of the nature and the motivations of our sources. The case studies of emperors are limited to the period from the establishment of the Principate up to the end of the Severan dynasty, culminating in the short reign of Elagabalus. -

The Madness of Isolation in Suetonius' “Caligula” and “Nero”

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Lewis Honors College Capstone Collection Lewis Honors College 2020 ‘De Monstris’: The Madness of Isolation in Suetonius’ “Caligula” and “Nero” Maya Menon University of Kentucky, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/honprog Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Menon, Maya, "‘De Monstris’: The Madness of Isolation in Suetonius’ “Caligula” and “Nero”" (2020). Lewis Honors College Capstone Collection. 50. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/honprog/50 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Lewis Honors College at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Lewis Honors College Capstone Collection by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ‘De Monstris’: The Madness of Isolation in Suetonius’ “Caligula” and “Nero” Maya Menon MCL 495-001: Capstone Dr. Matthew Wells December 2, 2020 Menon 2 The emperors Gaius Caesar ‘Caligula’ (r. 37-41 CE) and Nero (r. 54-68 CE) are regarded as some of Rome’s most infamous and notorious rulers due to their erratic, destructive, and complex behaviors. In his biographical work The Lives of the Caesars, the literary artist Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus (c. 69-122 CE) provides a concise, informative, and illustrative depiction of the reigns of these two emperors. Suetonius’ particular literary technique and style used in the narration for both Nero and Caligula contributes to an enduring legacy of madness and depravity that has been influential in our understanding of these two rulers well into the modern age. -

An Examination of Jerry Goldsmith's

THE FORBIDDEN ZONE, ESCAPING EARTH AND TONALITY: AN EXAMINATION OF JERRY GOLDSMITH’S TWELVE-TONE SCORE FOR PLANET OF THE APES VINCENT GASSI A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN MUSIC YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO MAY 2019 © VINCENT GASSI, 2019 ii ABSTRACT Jerry GoldsMith’s twelve-tone score for Planet of the Apes (1968) stands apart in Hollywood’s long history of tonal scores. His extensive use of tone rows and permutations throughout the entire score helped to create the diegetic world so integral to the success of the filM. GoldsMith’s formative years prior to 1967–his training and day to day experience of writing Music for draMatic situations—were critical factors in preparing hiM to meet this challenge. A review of the research on music and eMotion, together with an analysis of GoldsMith’s methods, shows how, in 1967, he was able to create an expressive twelve-tone score which supported the narrative of the filM. The score for Planet of the Apes Marks a pivotal moment in an industry with a long-standing bias toward modernist music. iii For Mary and Bruno Gassi. The gift of music you passed on was a game-changer. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Heartfelt thanks and much love go to my aMazing wife Alison and our awesome children, Daniela, Vince Jr., and Shira, without whose unending patience and encourageMent I could do nothing. I aM ever grateful to my brother Carmen Gassi, not only for introducing me to the music of Jerry GoldsMith, but also for our ongoing conversations over the years about filM music, composers, and composition in general; I’ve learned so much.