Mining Mnes' Community Risk Management Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Version of the Mediterranean Edition of the Handbook on Effective Labour Migration Policies, Edition of the Handbook on Effective Labour Migration Policies

Activity Report June 2007 – May 2008 Office of the Co-ordinator of OSCE Economic and Environmental Activities osce.org/eea Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe Activity Report June 2007 – May 2008 Office of the Co-ordinator of OSCE Economic and Environmental Activities Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe PUBLISHED BY Office of the Co-ordinator of OSCE Economic and Environmental Activities OSCE Secretariat Wallnerstrasse 6, A-1010 Vienna, Austria Tel: +43 1 514 36 6151 Fax: +43 1 514 36 6251 E-mail: [email protected] Vienna, May 2008 osce.org/eea This is not a consensus document. EDITORS Roel Janssens, Sergey Kostelyanyets, Gabriel Leonte, Kilian Strauss, Alexey Stukalo. DESIGN AND PRINTING Phoenix Design Aid A/S, Denmark. ISO 14001/ISO 9000 certified and EMAS-approved. Produced on 100% recycled paper (without chlorine) with vegetable-based inks. The printed matter is recyclable. PHOTOS All pictures unless indicated otherwise: OSCE Front cover pictures: Shamil Zhumatov and OSCE Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION BY THE CO-ORDINATOR OF OSCE ECONOMIC AND ENVIRONMENTAL ACTIVITIES 05 2. CURRENT ISSUES AND RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN THE ECONOMIC AND ENVIRONMENTAL DIMENSION 07 2.1 Political dialogue on topical Economical and Environmental issues 07 2.2 Enhancing synergies between Vienna and the OSCE field presences 10 3. THE 16TH ECONOMIC AND ENVIRONMENTAL FORUM 12 3.1 Helsinki Preparatory Conference 12 3.2 Vienna Forum 13 3.3 Ashgabad Preparatory Conference 14 4. GOOD GOVERNANCE: COMBATING CORRUPTION, MONEY LAUNDERING AND TERRORIST FINANCING 16 4.1 Promoting transparency and combating corruption 16 4.2 Strengthening of legislation and promotion of international standards 18 4.3 Activities aimed at combating money laundering and the financing of terrorism 19 5. -

Ra Vayots Dzor Marzma

RA VAYOTS DZOR MARZMA RA VAYOTS DZOR MARZ Marz centre - Eghegnadzor town Territories -Vayk and Eghegnadzor Towns - Eghegnadzor, Jermuk and Vayk RA Vayots Dzor marz is situated in Southern part of the Republic. In the South borders with Nakhijevan, in the North it borders with RA Grgharkunik marz, in the East – RA Syunik marz and in the West – RA Ararat marz. Territory 2308 square km Territory share of the marz in the territory of RA 7.8 % Urban communities 3 Rural communities 41 Towns 3 Villages 52 Population number as of January 1, 2006 55.8 ths. persons including urban 19.4 ths. persons rural 36.4 ths. persons Share of urban population size 34.8% Share of marz population size in RA population size, 2005 1.7% Agricultural land 209262 ha including - arable land 16287 ha Vayots dzor is surrounded with high mountains, water-separately mountain ranges, that being original natural banks between its and neighbouring territories, turn that into a geographical single whole. Vayots dzor marz has varied fauna and flora. Natural forests comprise 6.7% or 13240.1 ha of territory. Voyots dzor surface is extraordinary variegated. Volcanic forces, earthquakes, waters of Arpa river and its tributaries raised numerous mountain ranges stretching by different directions with big and small tops, mysterious canyons, mountain passes, plateaus, concavities, fields, meadows and natural varied buildings, the most bright example of which is Jermuk wonderful waterfall (60 m). Marzes of the Republic of Armenia in Figures, 2002-2006 269 The Vayots dzor climate on the whole is continental with cold or moderate cold winters and hot or warm summers. -

Natural Radioactivity in Urban Soils of Mining Centers in Armenia: Dose Rate and Risk Assessment

Chemosphere 225 (2019) 859e870 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Chemosphere journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/chemosphere Natural radioactivity in urban soils of mining centers in Armenia: Dose rate and risk assessment * Olga Belyaeva a, , Konstantin Pyuskyulyan a, b, Nona Movsisyan a, Armen Saghatelyan a, Fernando P. Carvalho c a Center for Ecological-Noosphere Studies (CENS) of NAS RA, 68 Abovyan Street, 0025 Yerevan, Armenia b Armenian Nuclear Power Plant, 0911 Metsamor, Armavir Marz, Armenia c Laboratorio de Protecçao~ e Segurança Radiologica, Instituto Superior Tecnico/Campus Tecnologico Nuclear, Universidade de Lisboa, Estrada Nacional 10, km 139,7, 2695-066 Bobadela LRS, Portugal highlights Soil radioactivity enheancemet was studied based on urban geochemical survey. Copper and polymetallic mining is the factor for natural radioactivity enheancement. Mining legacy sites located at high altitudes preovoke NORM accumulation in vales. Enhanced soil radioactivity due to metal mining is not risk factor to human health. article info abstract Article history: Soil radioactivity levels, dose rate and radiological health risk were assessed in metal mining centers of Received 10 December 2018 Armenia, at the towns of Kapan and Kajaran. Archive soil samples of the multipurpose soil surveys Received in revised form implemented in Kapan and Kajaran were used for estimation of total alpha and total beta activity levels 4 March 2019 using gas-less iMatic™ alpha/beta cօunting system (Canberra). Ten representative soil samples per town Accepted 10 March 2019 were randomly selected from different urban zones for naturally occurring radionuclide measurements Available online 11 March 2019 (238U, 232Th, 40 K) using high purity germanium detector. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents 1. Social Economic Background & Current Indicators of Syunik Region...........................2 2. Key Problems & Constraints .............................................................................................23 Objective Problems ...................................................................................................................23 Subjective Problems..................................................................................................................28 3. Assessment of Economic Resources & Potential ..............................................................32 Hydropower Generation............................................................................................................32 Tourism .....................................................................................................................................35 Electronics & Engineering ........................................................................................................44 Agriculture & Food Processing.................................................................................................47 Mineral Resources (other than copper & molybdenum)...........................................................52 Textiles......................................................................................................................................55 Infrastructures............................................................................................................................57 -

Development Project Ideas Goris, Tegh, Gorhayk, Meghri, Vayk

Ministry of Territorial Administration and Development of the Republic of Armenia DEVELOPMENT PROJECT IDEAS GORIS, TEGH, GORHAYK, MEGHRI, VAYK, JERMUK, ZARITAP, URTSADZOR, NOYEMBERYAN, KOGHB, AYRUM, SARAPAT, AMASIA, ASHOTSK, ARPI Expert Team Varazdat Karapetyan Artyom Grigoryan Artak Dadoyan Gagik Muradyan GIZ Coordinator Armen Keshishyan September 2016 List of Acronyms MTAD Ministry of Territorial Administration and Development ATDF Armenian Territorial Development Fund GIZ German Technical Cooperation LoGoPro GIZ Local Government Programme LSG Local Self-government (bodies) (FY)MDP Five-year Municipal Development Plan PACA Participatory Assessment of Competitive Advantages RDF «Regional Development Foundation» Company LED Local economic development 2 Contents List of Acronyms ........................................................................................................................ 2 Contents ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Structure of the Report .............................................................................................................. 5 Preamble ..................................................................................................................................... 7 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 9 Approaches to Project Implementation .................................................................................. -

(Amulsar Gold Mine) – Extension (48579) REQUEST NUMBER

OFFICIAL USE Lydian (Amulsar Gold Mine) – Extension (48579) REQUEST NUMBER: 2020/02 COMPLIANCE ASSESSMENT REPORT – November 2020 OFFICIAL USE OFFICIAL USE The Independent Project Accountability Mechanism (IPAM) is the accountability mechanism of the EBRD. It receives and independently reviews concerns raised by individuals or organisations about Bank-financed Projects, which are believed to have caused, or to be likely to cause, harm. The purpose of the mechanism is to facilitate the resolution of social, environmental and public disclosure issues among Project stakeholders; to determine whether the Bank has complied with its Environmental and Social Policy and the Project-specific provisions of its Access to Information Policy; and where applicable, to address any existing non-compliance with these policies, while preventing future non-compliance by the Bank. IPAM is an independent function, governed outside the Bank’s investment operations (i.e. outside of Bank management) with a direct reporting line to the Board of Directors through its Audit Committee. For more information about IPAM, contact us or visit https://www.ebrd.com/project- finance/ipam.html. Contact information: The Independent Project Accountability Mechanism (IPAM) European Bank for Reconstruction and Development One Exchange Square London EC2A 2JN Telephone: +44 (0)20 7338 6000 Fax: +44 (0)20 7338 7633 Email: [email protected] https://www.ebrd.com/project-finance/ipam.html How can IPAM address my concerns? Requests about the environmental, social and transparency performance -

ESIA Review the Republic of Armenia

Privileged & Confidential Amulsar Gold Mine ESIA Review The Republic of Armenia Independent 3rd Party Assessment Prepared For: of the Impacts on Water Investigative Committee of the Republic of Armenia Resources and Geology, Prepared By: Biodiversity and Air Quality ELARD Beirut, Lebanon July 22, 2019 TRC New Providence, New Jersey, USA Prepared by: David Hay, PhD, CPG Reviewed & Approved by: Nidal Rabah, PhD, PE, PM Water Resources and Geology Water Resources and Geology Prepared by: Robert Stanforth, PhD Reviewed & Approved by: Ramez Kayal, MSc Water Resources and Geology Water Resources and Geology Prepared by: Carla Khater, PhD Reviewed & Approved by: Ricardo Khoury, ME Biodiversity Biodiversity and Air Quality Prepared by: Alexandre Cluchier, MSc, EPHE Biodiversity Prepared by: Charbel Afif, PhD Air Quality Privileged & Confidential TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Objectives ........................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Scope of Assessment ......................................................................................................... 2 1.2.1 Assessment of the Impacts of Geology .................................................. 3 1.2.2 Assessment of the Impacts on Water Resources .................................. 3 1.2.3 Assessment of the Impacts on Biodiversity ............................................ 4 1.2.4 -

Genocide and Deportation of Azerbaijanis

GENOCIDE AND DEPORTATION OF AZERBAIJANIS C O N T E N T S General information........................................................................................................................... 3 Resettlement of Armenians to Azerbaijani lands and its grave consequences ................................ 5 Resettlement of Armenians from Iran ........................................................................................ 5 Resettlement of Armenians from Turkey ................................................................................... 8 Massacre and deportation of Azerbaijanis at the beginning of the 20th century .......................... 10 The massacres of 1905-1906. ..................................................................................................... 10 General information ................................................................................................................... 10 Genocide of Moslem Turks through 1905-1906 in Karabagh ...................................................... 13 Genocide of 1918-1920 ............................................................................................................... 15 Genocide over Azerbaijani nation in March of 1918 ................................................................... 15 Massacres in Baku. March 1918................................................................................................. 20 Massacres in Erivan Province (1918-1920) ............................................................................... -

Armenian Tourist Attraction

Armenian Tourist Attractions: Rediscover Armenia Guide http://mapy.mk.cvut.cz/data/Armenie-Armenia/all/Rediscover%20Arme... rediscover armenia guide armenia > tourism > rediscover armenia guide about cilicia | feedback | chat | © REDISCOVERING ARMENIA An Archaeological/Touristic Gazetteer and Map Set for the Historical Monuments of Armenia Brady Kiesling July 1999 Yerevan This document is for the benefit of all persons interested in Armenia; no restriction is placed on duplication for personal or professional use. The author would appreciate acknowledgment of the source of any substantial quotations from this work. 1 von 71 13.01.2009 23:05 Armenian Tourist Attractions: Rediscover Armenia Guide http://mapy.mk.cvut.cz/data/Armenie-Armenia/all/Rediscover%20Arme... REDISCOVERING ARMENIA Author’s Preface Sources and Methods Armenian Terms Useful for Getting Lost With Note on Monasteries (Vank) Bibliography EXPLORING ARAGATSOTN MARZ South from Ashtarak (Maps A, D) The South Slopes of Aragats (Map A) Climbing Mt. Aragats (Map A) North and West Around Aragats (Maps A, B) West/South from Talin (Map B) North from Ashtarak (Map A) EXPLORING ARARAT MARZ West of Yerevan (Maps C, D) South from Yerevan (Map C) To Ancient Dvin (Map C) Khor Virap and Artaxiasata (Map C Vedi and Eastward (Map C, inset) East from Yeraskh (Map C inset) St. Karapet Monastery* (Map C inset) EXPLORING ARMAVIR MARZ Echmiatsin and Environs (Map D) The Northeast Corner (Map D) Metsamor and Environs (Map D) Sardarapat and Ancient Armavir (Map D) Southwestern Armavir (advance permission -

5964Cded35508.Pdf

Identification and implementation of adaptation response to Climate Change impact for Conservation and Sustainable use of agro-biodiversity in arid and semi- arid ecosystems of South Caucasus Ecosystem Assessment Report Erevan, 2012 Executive Summary Armenia is a mountainous country, which is distinguished with vulnerable ecosystems, dry climate, with active external and desertification processes and frequency of natural disasters. Country’s total area is 29.743 sq/km. 76.5% of total area is situated on the altitudes of 1000-2500m above sea level. There are seven types of landscapes in Armenia, with diversity of their plant symbiosis and species. All Caucasus main flora formations (except humid subtropical vegetation) and 50% of the Caucasus high quality flower plant species, including species endowed with many nutrient, fodder, herbal, paint and other characteristics are represented here. “Identification and implementation of adaptation response to Climate Change impact for Conservation and Sustainable use of agro biodiversity in arid and semi-arid ecosystems of South Caucasus” project is aimed to identify the most vulnerable ecosystems in RA, in light of climate change, assess their current conditions, vulnerability level of surrounding communities and the extend of impact on ecosystems by community members related to it. During the project, an initial assessment has been conducted in arid and semi arid ecosystems of Armenia to reveal the most vulnerable areas to climate change, major threats have been identified, main environmental issues: major challenges and problems of arid and semi arid ecosystems and nearly located local communities have been analyzed and assessed. Ararat and Vets Door regions are recognized as the most vulnerable areas towards climate change, where vulnerable ecosystems are dominant. -

Results of Soil and Water Testing in Kindergartens and Schools of Kajaran and Artsvanik Communities, Syuniq Marz, Republic of Armenia

Results of Soil and Water Testing in Kindergartens and Schools of Kajaran and Artsvanik Communities, Syuniq Marz, Republic of Armenia Prepared by AUA Center for Responsible Mining Funded by OneArmenia’s crowdfunding campaign “Let’s Protect Armenia from Toxic Pollution” Equipment donated by Organization for Cooperation and Security in Europe (OSCE) Yerevan United Nations Development Program (UNDP) Armenia September 2016 Results Soil & Water Testing in Kindergartens & Schools, Kajaran and Artsvanik Communities, RA (Version Sep 8, 2016) TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................................................ 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................................................... 3 OVERVIEW AND KEY FINDINGS................................................................................................. 4 BACKGROUND ON KAJARAN AND ARTSVANIK COMMUNITIES .............................................. 9 BIBLIOGRAPHY ......................................................................................................................... 14 ANNEXES .................................................................................................................................. 16 Annex 1. Population of Kajaran city by age and sex ............................................................................. 17 Annex 2. Methodology on Soil Sampling and Testing.......................................................................... -

Page 1 Establishment of Computer Labs in 50 Schools of Vayots Dzor

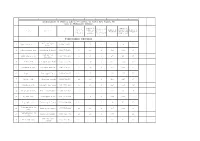

Establishment of Computer Labs in 50 schools of Vayots Dzor Region, RA List of beneficiary schools Number of Number of Current Numbers of computers Number of students in Number of School Director Tel. number of printers to to be students middle and teachers computers be donated donated high school Yeghegnadzor subregion Hovhannisyan 1 Agarakadzor sch. 093-642-031 10 1 121 79 27 Naira 2 Aghavnadzor sch. Manukyan Nahapet 091-726-908 2 10 1 230 130 32 Yedigaryan 3 Aghnjadzor sch. 093-832-130 0 5 1 46 26 16 Hrachya 4 Areni sch. Hayrapetyan Avet 093-933-780 0 10 1 221 130 29 5 Artabuynq sch. Babayan Mesrop 096-339-704 2 10 1 157 100 24 6 Arpi sch. Hovsepyan Ara 093-763-173 0 10 1 165 120 22 7 Getap sch. Qocharyan Taguhi 093-539-488 10 10 1 203 126 35 8 Gladzor sch. Hayrapetyan Arus 093-885-120 0 10 1 243 110 32 9 Goghtanik sch. Asatryan Anahit 094-305-857 0 1 1 15 5 8 10 Yelpin sch. Gevorgyan Jora 093-224-336 4 6 1 186 100 27 11 Yeghegis sch. Tadevosyan Levon 077-119-399 0 7 1 59 47 23 Yeghegnadzor N1 12 Grigoryan Anush 077-724-982 10 10 1 385 201 48 sch. Yeghegnadzor N2 13 Sargsyan Anahit 099-622-362 15 10 1 366 41 sch. Khachatryan 14 Taratumb sch. 093-327-403 0 7 1 59 47 17 Zohrab 15 Khachik sch. Tadevosyan Surik 093-780-399 0 8 1 106 55 22 16 Hermon sch.