Sweeney Todd's Indian Empire: Mapping the East India Company In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jack the Ripper: the Divided Self and the Alien Other in Late-Victorian Culture and Society

Jack the Ripper: The Divided Self and the Alien Other in Late-Victorian Culture and Society Michael Plater Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 18 July 2018 Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne ii ABSTRACT This thesis examines late nineteenth-century public and media representations of the infamous “Jack the Ripper” murders of 1888. Focusing on two of the most popular theories of the day – Jack as exotic “alien” foreigner and Jack as divided British “gentleman” – it contends that these representations drew upon a series of emergent social and cultural anxieties in relation to notions of the “self” and the “other.” Examining the widespread contention that “no Englishman” could have committed the crimes, it explores late-Victorian conceptions of Englishness and documents the way in which the Ripper crimes represented a threat to these dominant notions of British identity and masculinity. In doing so, it argues that late-Victorian fears of the external, foreign “other” ultimately masked deeper anxieties relating to the hidden, unconscious, instinctual self and the “other within.” Moreover, it reveals how these psychological concerns were connected to emergent social anxieties regarding degeneration, atavism and the “beast in man.” As such, it evaluates the wider psychological and sociological impact of the case, arguing that the crimes revealed the deep sense of fracture, duality and instability that lay beneath the surface of late-Victorian English life, undermining and challenging dominant notions of progress, civilisation and social advancement. Situating the Ripper narrative within a broader framework of late-nineteenth century cultural uncertainty and crisis, it therefore argues that the crimes (and, more specifically, populist perceptions of these crimes) represented a key defining moment in British history, serving to condense and consolidate a whole series of late-Victorian fears in relation to selfhood and identity. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

Artswest Playhouse and Gallery Announces UNCHARTED the 2016-2017 Season

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Date: May 12, 2016 Contact: Laura Lee Email: [email protected] Phone: (206) 938-0963, ext. 114 ArtsWest Playhouse and Gallery announces UNCHARTED the 2016-2017 Season SEATTLE, WA (May 12, 2016) – ArtsWest Artistic Director Mathew Wright has announced his second season, running September 2016 through July 2017. Opening with acclaimed dramatist Terrence McNally’s MOTHERS AND SONS, the six production season will include the magical story telling of PETER AND THE STARCATCHER based on the novel by Dave Barry & Ridley Pearson; an Olivier Award winning new adaptation of Henrik Ibsen’s GHOSTS; a piercing glimpse into the teen-age world in Kirsten Greenidge’s MILK LIKE SUGAR; Byrony Lavery’s unflinching drama FROZEN; and the Stephen Sondheim musical thriller SWEENEY TODD. “Through a variety of lenses, periods and styles, we are looking at the ways in which parents and children navigate the seemingly uncharted path out of childhood and into adulthood.” shares Artistic Director Mathew Wright. In addition to the six show season, ArtsWest is pleased to announce a co-production with ACT and Circle X Theatre Co. in the presentation of an incendiary new rock musical BAD APPLES, directed by ACT Artistic Director John Langs at ACT’s Falls Theatre in the fall of 2016. MOTHERS AND SONS By Terrence McNally September 22 – October 23, 2016 2014 Tony Award Nominated Best Play 2014 Drama League Nominated Outstanding Play By turns smartly funny and powerfully resonant, this latest play from acclaimed dramatist Terrence McNally (Love! Valour! Compassion! Corpus Christi, Master Class) portrays a woman who pays an unexpected visit to the New York apartment of her late son’s partner, who is now married to another man and has a young son. -

Big Hits Karaoke Song Book

Big Hits Karaoke Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID 3OH!3 Angus & Julia Stone You're Gonna Love This BHK034-11 And The Boys BHK004-03 3OH!3 & Katy Perry Big Jet Plane BHKSFE02-07 Starstruck BHK001-08 Ariana Grande 3OH!3 & Kesha One Last Time BHK062-10 My First Kiss BHK010-01 Ariana Grande & Iggy Azalea 5 Seconds Of Summer Problem BHK053-02 Amnesia BHK055-06 Ariana Grande & Weeknd She Looks So Perfect BHK051-02 Love Me Harder BHK060-10 ABBA Ariana Grande & Zedd Waterloo BHKP001-04 Break Free BHK055-02 Absent Friends Armin Van Buuren I Don't Wanna Be With Nobody But You BHK000-02 This Is What It Feels Like BHK042-06 I Don't Wanna Be With Nobody But You BHKSFE01-02 Augie March AC-DC One Crowded Hour BHKSFE02-06 Long Way To The Top BHKP001-05 Avalanche City You Shook Me All Night Long BHPRC001-05 Love, Love, Love BHK018-13 Adam Lambert Avener Ghost Town BHK064-06 Fade Out Lines BHK060-09 If I Had You BHK010-04 Averil Lavinge Whataya Want From Me BHK007-06 Smile BHK018-03 Adele Avicii Hello BHK068-09 Addicted To You BHK049-06 Rolling In The Deep BHK018-07 Days, The BHK058-01 Rumour Has It BHK026-05 Hey Brother BHK047-06 Set Fire To The Rain BHK021-03 Nights, The BHK061-10 Skyfall BHK036-07 Waiting For Love BHK065-06 Someone Like You BHK017-09 Wake Me Up BHK044-02 Turning Tables BHK030-01 Avicii & Nicky Romero Afrojack & Eva Simons I Could Be The One BHK040-10 Take Over Control BHK016-08 Avril Lavigne Afrojack & Spree Wilson Alice (Underground) BHK006-04 Spark, The BHK049-11 Here's To Never Growing Up BHK042-09 -

Mehendale Book-10418

Tipu as He Really Was Gajanan Bhaskar Mehendale Tipu as He Really Was Copyright © Gajanan Bhaskar Mehendale First Edition : April, 2018 Type Setting and Layout : Mrs. Rohini R. Ambudkar III Preface Tipu is an object of reverence in Pakistan; naturally so, as he lived and died for Islam. A Street in Islamabad (Rawalpindi) is named after him. A missile developed by Pakistan bears his name. Even in India there is no lack of his admirers. Recently the Government of Karnataka decided to celebrate his birth anniversary, a decision which generated considerable opposition. While the official line was that Tipu was a freedom fighter, a liberal, tolerant and enlightened ruler, its opponents accused that he was a bigot, a mass murderer, a rapist. This book is written to show him as he really was. To state it briefly: If Tipu would have been allowed to have his way, most probably, there would have been, besides an East and a West Pakistan, a South Pakistan as well. At the least there would have been a refractory state like the Nizam's. His suppression in 1792, and ultimate destruction in 1799, had therefore a profound impact on the history of India. There is a class of historians who, for a long time, are portraying Tipu as a benevolent ruler. To counter them I can do no better than to follow Dr. R. C. Majumdar: “This … tendency”, he writes, “to make history the vehicle of certain definite political, social and economic ideas, which reign supreme in each country for the time being, is like a cloud, at present no bigger than a man's hand, but which may soon grow in volume, and overcast the sky, covering the light of the world by an impenetrable gloom. -

Introduction to Text Analysis: a Coursebook

Table of Contents 1. Preface 1.1 2. Acknowledgements 1.2 3. Introduction 1.3 1. For Instructors 1.3.1 2. For Students 1.3.2 3. Schedule 1.3.3 4. Issues in Digital Text Analysis 1.4 1. Why Read with a Computer? 1.4.1 2. Google NGram Viewer 1.4.2 3. Exercises 1.4.3 5. Close Reading 1.5 1. Close Reading and Sources 1.5.1 2. Prism Part One 1.5.2 3. Exercises 1.5.3 6. Crowdsourcing 1.6 1. Crowdsourcing 1.6.1 2. Prism Part Two 1.6.2 3. Exercises 1.6.3 7. Digital Archives 1.7 1. Text Encoding Initiative 1.7.1 2. NINES and Digital Archives 1.7.2 3. Exercises 1.7.3 8. Data Cleaning 1.8 1. Problems with Data 1.8.1 2. Zotero 1.8.2 3. Exercises 1.8.3 9. Cyborg Readers 1.9 1. How Computers Read Texts 1.9.1 2. Voyant Part One 1.9.2 3. Exercises 1.9.3 10. Reading at Scale 1.10 1. Distant Reading 1.10.1 2. Voyant Part Two 1.10.2 3. Exercises 1.10.3 11. Topic Modeling 1.11 1. Bags of Words 1.11.1 2. Topic Modeling Case Study 1.11.2 3. Exercises 1.11.3 12. Classifiers 1.12 1. Supervised Classifiers 1.12.1 2. Classifying Texts 1.12.2 3. Exercises 1.12.3 13. Sentiment Analysis 1.13 1. Sentiment Analysis 1.13.1 2. -

Women at Crossroads: Multi- Disciplinary Perspectives’

ISSN 2395-4396 (Online) National Seminar on ‘Women at Crossroads: Multi- disciplinary Perspectives’ Publication Partner: IJARIIE ORGANISE BY: DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH PSGR KRISHNAMMAL COLLEGE FOR WOMEN, PEELAMEDU, COIMBATORE Volume-2, Issue-6, 2017 Vol-2 Issue-6 2017 IJARIIE-ISSN (O)-2395-4396 A Comparative Study of the Role of Women in New Generation Malayalam Films and Serials Jibin Francis Research Scholar Department of English PSG College of Arts and Science, Coimbatore Abstract This 21st century is called the era of technology, which witnesses revolutionary developments in every aspect of life. The life style of the 21st century people is very different; their attitude and culture have changed .This change of viewpoint is visible in every field of life including Film and television. Nowadays there are several realty shows capturing the attention of the people. The electronic media influence the mind of people. Different television programs target different categories of people .For example the cartoon programs target kids; the realty shows target youth. The points of view of the directors and audience are changing in the modern era. In earlier time, women had only a decorative role in the films. Their representation was merely for satisfying the needs of men. The roles of women were always under the norms and rules of the patriarchal society. They were most often presented on the screen as sexual objects .Here women were abused twice, first by the male character in the film and second, by the spectators. But now the scenario is different. The viewpoint of the directors as well as the audience has drastically changed .In this era the directors are courageous enough to make films with women as central characters. -

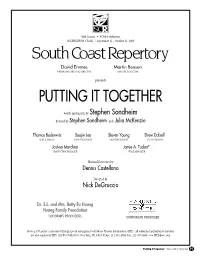

Putting It Together

46th Season • 437th Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / September 11 - October 11, 2009 David Emmes Martin Benson Producing ArtiStic director ArtiStic director presents PUTTING IT TOGETHER words and music by Stephen Sondheim devised by Stephen Sondheim and Julia McKenzie Thomas Buderwitz Soojin Lee Steven Young Drew Dalzell Scenic deSign coStume deSign Lighting deSign Sound deSign Joshua Marchesi Jamie A. Tucker* Production mAnAger StAge mAnAger musical direction by Dennis Castellano directed by Nick DeGruccio Dr. S.L. and Mrs. Betty Eu Huang Huang Family Foundation honorAry ProducerS corPorAte Producer Putting It Together is presented through special arrangement with music theatre international (mti). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by mti. 421 West 54th Street, new york, ny 10019; Phone: 212-541-4684 Fax: 212-397-4684; www.mtiShows.com Putting It Together• SOUTH COA S T REPE R TO R Y P1 THE CAST (in order of appearance) Matt McGrath* Harry Groener* Niki Scalera* Dan Callaway* Mary Gordon Murray* MUSICIANS Dennis Castellano (conductor/keyboards), John Glaudini (synthesizer), John Reilly (woodwinds), Louis Allee (percussion) SETTING A New York penthouse apartment. Now. LENGTH Approximately two hours including one 15-minute intermission. PRODUCTION STAFF Casting ................................................................................ Joanne DeNaut, CSA Dramaturg .......................................................................... Linda Sullivan Baity Assistant Stage Manager ............................................................. -

Lublin Studies in Modern Languages and Literature

Lublin Studies in Modern Languages and Literature VOL. 43 No 2 (2019) ii e-ISSN: 2450-4580 Publisher: Maria Curie-Skłodowska University Lublin, Poland Maria Curie-Skłodowska University Press MCSU Library building, 3rd floor ul. Idziego Radziszewskiego 11, 20-031 Lublin, Poland phone: (081) 537 53 04 e-mail: [email protected] www.wydawnictwo.umcs.lublin.pl Editorial Board Editor-in-Chief Jolanta Knieja, Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, Lublin, Poland Deputy Editors-in-Chief Jarosław Krajka, Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, Lublin, Poland Anna Maziarczyk, Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, Lublin, Poland Statistical Editor Tomasz Krajka, Lublin University of Technology, Poland International Advisory Board Anikó Ádám, Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Hungary Monika Adamczyk-Garbowska, Maria Curie-Sklodowska University, Poland Ruba Fahmi Bataineh, Yarmouk University, Jordan Alejandro Curado, University of Extramadura, Spain Saadiyah Darus, National University of Malaysia, Malaysia Janusz Golec, Maria Curie-Sklodowska University, Poland Margot Heinemann, Leipzig University, Germany Christophe Ippolito, Georgia Institute of Technology, United States of America Vita Kalnberzina, University of Riga, Latvia Henryk Kardela, Maria Curie-Sklodowska University, Poland Ferit Kilickaya, Mehmet Akif Ersoy University, Turkey Laure Lévêque, University of Toulon, France Heinz-Helmut Lüger, University of Koblenz-Landau, Germany Peter Schnyder, University of Upper Alsace, France Alain Vuillemin, Artois University, France v Indexing Peer Review Process 1. Each article is reviewed by two independent reviewers not affiliated to the place of work of the author of the article or the publisher. 2. For publications in foreign languages, at least one reviewer’s affiliation should be in a different country than the country of the author of the article. -

Six Characters in Search of an Author by Luigi Pirandello

McCoy Theatre Rhodes College presents Music by: Book adapted from Voltaire by: Lyrics by: Leornard Bernstein Hugh Wheeler Richard Wilbur Six Characters In Search Of An Author by Luigi Pirandello Season 10 McCoy Theatre Rhodes College presents Six Characters In Search Of An Author by Luigi Pirandello Directed by Elfin Frederick Vogel McCoy Visiting Artist Guest Director Assistant Director Misty Wakeland Technical Director Steve Jones Set Designer Steve Jones Lighting Designer Kristina Kloss Costume Designer David Jilg Assistant Costumer Charlotte Higginbotham Stage Manager Tracy Castleberry Assistant Stage Manager Louise Casini produced by special arrangement with Samuel French, Inc. 7 Six Characters in Search of an Author Cast Father ..............................................................Albert Hoagbarth Mother ..................................................................... Dina Facklis Stepdaughter ................................................... Catherine Eckman Son ...................................................................... Eric Underdahl Madame Pace ...................................................... Kimberly Groat Little Girl .................................................................Alison Kamhi Little Boy .....................................................................Tim Olcott Director .......................................................................Chris Hall Lead Actor........ .......................................................John Nichols Lead Actress ......................................................... -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/30/2021 04:26:46AM Via Free Access List of Illustrations / Image Quotations

list of illustrations / image quotations becker Histories, ed. Monica Juneja), London , p. . Yang Zhichao: Planting Grass (performance docu- . M. F. Husain: Untitled (later captioned Bharat Mata, mentation), Nov. , , Suzhou Road, Shanghai Mother India), Acrylic on canvas, Image source: https://transgressivechineseart.files.wordpress. In Sumathi Ramaswamy (ed.): Barefoot across the Nation. M. com///yang-zhichoa-planting-grass.jpg) F. Husain and the Idea of India (Series Visual and Media His- . Zhu Yu: Eating People, (performance documenta- tories, ed. Monica Juneja), London , p. tion), Sept. , Shanghai . Young woman painting her eyes, detail from temple Image source: http://media.tumblr.com/tumblr_ljdpccdK- frieze, Parshvanath temple, Khajuraho, ca. C.E. bqhbuj.jpg) Photograph by Jean-Pierre Dalbéra, Paris . M. F. Husain: Installation, Husain ki Sarai, Faridabad, frembgen / jehangir . . Billboard advertising the Bollywood movie Dirty Picture, In Pradeep Chandra: M. F. Husain. A Pictorial Tribute, New Metropole Cinema, Abbot Road, Lahore Delhi , p. . Scene from the violence-ridden film Guddu Badshah, . M. F. Husain: Between the Spider and the Lamp, oil placard, Lahore on board, . Women with gun from the film Bloody Mission, plac- In Sumathi Ramaswamy (ed.): Barefoot across the Nation. ard, Lahore M.F. Husain and the Idea of India (Series Visual and Media . Three females with a simpleton from the film Bhola Histories, ed. Monica Juneja), London , p. Sajan, placard, Lahore . M. F. Husain: From Mother Theresa Series, oil on . Placard advertising a typical Punjabi action movie, canvas, Lahore In Pradeep Chandra: M. F. Husain. A Pictorial Tribute, New . Female dancer, placard, Lahore Delhi , p. . Poster advertising the film Quarter of Sin, Pakistan . -

ORSI LIBRI a Late Summer Miscellany 2021

ORSI LIBRI A Late Summer Miscellany 2021 ORSI LIBRI Federico Orsi Antiquarian Bookseller ALAI & ILAB Member Corso Venezia, 29, 20121 Milan, Italy Website www.orsilibri.com – Instagram @orsilibri For any queries, write to [email protected] or ContaCt us at this telephone number: +39 351 5242260 Front Cover: detail of item no. 5. Back Cover: detail of item no. 12. P. IVA (VAT No.) IT11119040969 C. F. RSOFRC87M19G752V PEC [email protected] Detail of item no. 5. RARE THIRD EDITION 1. AN EMINENT WITCRACKER (pseud.), and George CRUICKSHANK, ill. Wit and Wisdom, or the World's Jest-Book: Forming a Rich Banquet of Anecdote and Wit, Expressly Calculated "to Set the Table in a Roar"; Being, Also, an Agreeable Travelling Companion. The Whole Arranged by an Eminent Wit-Cracker, “a Fellow of Infinite Jest”. London, Joseph Smith, 1834. €300 12mo, 576 pp., with several engraved half-page vignettes in the text and one full-paged. Frontispiece plate signed by William Chester Walker (1823-1872, fl.). Illustrations engraved probably after Cruickshank’s sketches. Quarter gilt leather and marbled paper over pasteboard. Some early pencil annotations throughout. First leaf partially teared, with no loss. Rare. The first edition was printed in 1826, the second in 1828. A VERY INTRIGUING LITTLE BOOK OF THE UTMOST RARITY 2. ANON. Les Delices des poesies de la Muse gailliarde et heroique de ce temps augmentez des verites italiennes et de Plusieurs autres pieces nouvelles… Imprimé cette année. S. l., s. n., n. d. [1675?] €1400 FIRST and ONLY edition. 12mo, 96 pp., title within a beautiful and charming woodcut border.