Stonewall Riots by Andrew Matzner the Stonewall Inn in 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jun Jul. 1970, Vol. 14 No. 09-10

Published bi-monthly by the Daughters of ONCE MORE WITH FEELING Bilitis, Inc., a non-profit corporation, at THE I have discovered my most unpleasant task as editor . having to remind y. 'i P.O. Box 5025, Washington Station, now and again of your duty as concerned reader. Not just reader, concern« ' reader. Reno, Nevada 89503. UDDER VOLUME 14 No. 9 and 10 If you aren’t — you ought to be. JUNE/JULY, 1970 Those of you who have been around three or more years of our fifteen years n a t io n a l OFFICERS, DAUGHTERS OF BILITIS, INC know the strides DOB has made and the effort we are making to improve this magazine. To continue growing as an organization we need more women, women . Rita Laporte aware they are women as well as Lesbians. If you have shy friends who might be President . jess K. Lane interested in DOB but who are, for real or imagined reasons, afraid to join us — i t h e l a d d e r , a copy of WHAT i w r ■ ’ '^hich shows why NO U N t at any time in any way is ever jeopardized by belonging to DOB or by t h e LADDER STAFF subscribing to THE LADDER. You can send this to your friend(s) and thus, almost surely bring more people to help in the battle. Gene Damon Editor ....................... Lyn Collins, Kim Stabinski, And for you new people, our new subscribers and members in newly formed and Production Assistants King Kelly, Ann Brady forming chapters, have you a talent we can use in THE LADDER? We need Bobin and Dana Jordan wnters always in all areas, fiction, non-fiction, biography, poetry. -

Vision for Change: Acceptance Without Exception for Trans People

A VISION FOR CHANGE Acceptance without exception for trans people 2017-2022 A VISION FOR CHANGE Acceptance without exception for trans people Produced by Stonewall Trans Advisory Group Published by Stonewall [email protected] www.stonewall.org.uk/trans A VISION FOR CHANGE Acceptance without exception for trans people 2017-2022 CONTENTS PAGE 5 INTRODUCTION FROM STONEWALL’S TRANS ADVISORY GROUP PAGE 6 INTRODUCTION FROM RUTH HUNT, CHIEF EXECUTIVE, STONEWALL PAGE 7 HOW TO READ THIS DOCUMENT PAGE 8 A NOTE ON LANGUAGE PAGE 9 EMPOWERING INDIVIDUALS: enabling full participation in everyday and public life by empowering trans people, changing hearts and minds, and creating a network of allies PAGE 9 −−THE CURRENT LANDSCAPE: o Role models o Representation of trans people in public life o Representation of trans people in media o Diversity of experiences o LGBT communities o Role of allies PAGE 11 −−VISION FOR CHANGE PAGE 12 −−STONEWALL’S RESPONSE PAGE 14 −−WHAT OTHERS CAN DO PAGE 16 TRANSFORMING INSTITUTIONS: improving services and workplaces for trans people PAGE 16 −−THE CURRENT LANDSCAPE: o Children, young people and education o Employment o Faith o Hate crime, the Criminal Justice System and support services o Health and social care o Sport PAGE 20 −−VISION FOR CHANGE PAGE 21 −−WHAT SERVICE PROVIDERS CAN DO PAGE 26 −−STONEWALL’S RESPONSE PAGE 28 −−WHAT OTHERS CAN DO PAGE 30 CHANGING LAWS: ensuring equal rights, responsibilities and legal protections for trans people PAGE 30 −−THE CURRENT LANDSCAPE: o The Gender Recognition Act o The Equality Act o Families and marriage o Sex by deception o Recording gender o Asylum PAGE 32 −−VISION FOR CHANGE PAGE 33 −−STONEWALL’S RESPONSE PAGE 34 −−WHAT OTHERS CAN DO PAGE 36 GETTING INVOLVED PAGE 38 GLOSSARY INTRODUCTION FROM STONEWALL’S TRANS ADVISORY GROUP The UK has played an While many of us benefited from the work to give a voice to all parts of trans successes of this time, many more communities, and we are determined important role in the did not. -

Hair: the Performance of Rebellion in American Musical Theatre of the 1960S’

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Winchester Research Repository University of Winchester ‘Hair: The Performance of Rebellion in American Musical Theatre of the 1960s’ Sarah Elisabeth Browne ORCID: 0000-0003-2002-9794 Doctor of Philosophy December 2017 This Thesis has been completed as a requirement for a postgraduate research degree of the University of Winchester MPhil/PhD THESES OPEN ACCESS / EMBARGO AGREEMENT FORM This Agreement should be completed, signed and bound with the hard copy of the thesis and also included in the e-copy. (see Thesis Presentation Guidelines for details). Access Permissions and Transfer of Non-Exclusive Rights By giving permission you understand that your thesis will be accessible to a wide variety of people and institutions – including automated agents – via the World Wide Web and that an electronic copy of your thesis may also be included in the British Library Electronic Theses On-line System (EThOS). Once the Work is deposited, a citation to the Work will always remain visible. Removal of the Work can be made after discussion with the University of Winchester’s Research Repository, who shall make best efforts to ensure removal of the Work from any third party with whom the University of Winchester’s Research Repository has an agreement. Agreement: I understand that the thesis listed on this form will be deposited in the University of Winchester’s Research Repository, and by giving permission to the University of Winchester to make my thesis publically available I agree that the: • University of Winchester’s Research Repository administrators or any third party with whom the University of Winchester’s Research Repository has an agreement to do so may, without changing content, translate the Work to any medium or format for the purpose of future preservation and accessibility. -

Bohemian Space and Countercultural Place in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2017 Hippieland: Bohemian Space and Countercultural Place in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood Kevin Mercer University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Mercer, Kevin, "Hippieland: Bohemian Space and Countercultural Place in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5540. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5540 HIPPIELAND: BOHEMIAN SPACE AND COUNTERCULTURAL PLACE IN SAN FRANCISCO’S HAIGHT-ASHBURY NEIGHBORHOOD by KEVIN MITCHELL MERCER B.A. University of Central Florida, 2012 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2017 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the birth of the late 1960s counterculture in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood. Surveying the area through a lens of geographic place and space, this research will look at the historical factors that led to the rise of a counterculture here. To contextualize this development, it is necessary to examine the development of a cosmopolitan neighborhood after World War II that was multicultural and bohemian into something culturally unique. -

Hair for Rent: How the Idioms of Rock 'N' Roll Are Spoken Through the Melodic Language of Two Rock Musicals

HAIR FOR RENT: HOW THE IDIOMS OF ROCK 'N' ROLL ARE SPOKEN THROUGH THE MELODIC LANGUAGE OF TWO ROCK MUSICALS A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Eryn Stark August, 2015 HAIR FOR RENT: HOW THE IDIOMS OF ROCK 'N' ROLL ARE SPOKEN THROUGH THE MELODIC LANGUAGE OF TWO ROCK MUSICALS Eryn Stark Thesis Approved: Accepted: _____________________________ _________________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Nikola Resanovic Dr. Chand Midha _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Interim Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. Rex Ramsier _______________________________ _______________________________ Department Chair or School Director Date Dr. Ann Usher ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................. iv CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................1 II. BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY ...............................................................................3 A History of the Rock Musical: Defining A Generation .........................................3 Hair-brained ...............................................................................................12 IndiffeRent .................................................................................................16 III. EDITORIAL METHOD ..............................................................................................20 -

The Year 1969 Marked a Major Turning Point in the Politics of Sexuality

The Gay Pride March, begun in 1970 as the In the fertile and tumultuous year that Christopher Street Liberation Day Parade to followed, groups such as the Gay commemorate the Stonewall Riots, became an Liberation Front (GLF), Gay Activists annual event, and LGBT Pride months are now celebrated around the world. The march, Alliance (GAA), and Radicalesbians Marsha P. Johnson handing out flyers in support of gay students at NYU, 1970. Photograph by Mattachine Society of New York. “Where Were Diana Davies. Diana Davies Papers. which demonstrates gays, You During the Christopher Street Riots,” The year 1969 marked 1969. Mattachine Society of New York Records. sent small groups of activists on road lesbians, and transgender people a major turning point trips to spread the word. Chapters sprang Gay Activists Alliance. “Lambda,” 1970. Gay Activists Alliance Records. Gay Liberation Front members marching as articulate constituencies, on Times Square, 1969. Photograph by up across the country, and members fought for civil rights in the politics of sexuality Mattachine Society of New York. Diana Davies. Diana Davies Papers. “Homosexuals Are Different,” 1960s. in their home communities. GAA became a major activist has become a living symbol of Mattachine Society of New York Records. in America. Same-sex relationships were discreetly force, and its SoHo community center, the Firehouse, the evolution of LGBT political tolerated in 19th-century America in the form of romantic Jim Owles. Draft of letter to Governor Nelson A. became a nexus for New York City gays and lesbians. Rockefeller, 1970. Gay Activists Alliance Records. friendships, but the 20th century brought increasing legal communities. -

OUT of the PAST Teachers’Guide

OUT OF THE PAST Teachers’Guide A publication of GLSEN, the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network Page 1 Out of the Past Teachers’ Guide Table of Contents Why LGBT History? 2 Goals and Objectives 3 Why Out of the Past? 3 Using Out of the Past 4 Historical Segments of Out of the Past: Michael Wigglesworth 7 Sarah Orne Jewett 10 Henry Gerber 12 Bayard Rustin 15 Barbara Gittings 18 Kelli Peterson 21 OTP Glossary 24 Bibliography 25 Out of the Past Honors and Awards 26 ©1999 GLSEN Page 2 Out of the Past Teachers’ Guide Why LGBT History? It is commonly thought that Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgendered (LGBT) history is only for LGBT people. This is a false assumption. In out current age of a continually expanding communication network, a given individual will inevitably e interacting with thousands of people, many of them of other nationalities, of other races, and many of them LGBT. Thus, it is crucial for all people to understand the past and possible contributions of all others. There is no room in our society for bigotry, for prejudiced views, or for the simple omission of any group from public knowledge. In acknowledging LGBT history, one teaches respect for all people, regardless of race, gender, nationality, or sexual orientation. By recognizing the accomplishments of LGBT people in our common history, we are also recognizing that LGBT history affects all of us. The people presented here are not amazing because they are LGBT, but because they accomplished great feats of intellect and action. These accomplishments are amplified when we consider the amount of energy these people were required to expend fighting for recognition in a society which refused to accept their contributions because of their sexuality, or fighting their own fear and self-condemnation, as in the case of Michael Wigglesworth and countless others. -

Title 175. Oklahoma State Board of Cosmetology Rules

TITLE 175. OKLAHOMA STATE BOARD OF COSMETOLOGY RULES AND REGULATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page Chapter 1. Administrative Operations 1-7 Subchapter 1. General Provisions 175:1-1-1 1 Subchapter 3. Board Structure and Agency Administration 175:1-3-1 2 Subchapter 5. Rules of Practice 175:1-5-1 3 Subchapter 7. Board Records and Forms 175:1-7-1 7 Chapter 10. Licensure of Cosmetologists and Related Establishments 7-51 Subchapter 1. General Provisions 175:10-1-1 7 Subchapter 3. Licensure of Cosmetology Schools 175:10-3-1 7 Subchapter 5. Licensure of Cosmetology Establishments 175:10-5-1 33 Subchapter 7. Sanitation and Safety Standards for Salons, 175:10-9-1 34 And Related Establishments Subchapter 9. Licensure of Cosmetologists and Related 175:10-9-1 39 Occupations Subchapter 11. License Renewal, Fees and Penalties 175:10-11-1 48 Subchapter 13. Reciprocal and Crossover Licensing 175:10-13-1 49 Subchapter 15. Inspections, Violations and Enforcement 175:10-15-1 50 Subchapter 17. Emergency Cosmetology Services 175:10-17-1 51 [Source: Codified 12-31-91] [Source: Amended: 7-1-93] [Source: Amended 7-1-96] [Source: Amended 7-26-99] [Source: Amended: 8-19-99] [Source: Amended 8-11-00] [Source: Amended 7-1-03] [Source: Amended 7-1-04] [Source: Amended 7-1-07] [Source: Amended 7-1-09] [Source: Amended 7-1-2012] COSMETOLOGY LAW Cosmetology Law - Title 59 O.S. Sections 199.1 et seq 52-63 State of Oklahoma Oklahoma State Board of Cosmetology I, Sherry G. Lewelling, Executive Director and the members of the Oklahoma State Board of Cosmetology do hereby certify that the Oklahoma Cosmetology Law, Rules and Regulations printed in this revision are true and correct. -

Presidential Documents Vol

42215 Federal Register Presidential Documents Vol. 81, No. 125 Wednesday, June 29, 2016 Title 3— Proclamation 9465 of June 24, 2016 The President Establishment of the Stonewall National Monument By the President of the United States of America A Proclamation Christopher Park, a historic community park located immediately across the street from the Stonewall Inn in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of New York City (City), is a place for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community to assemble for marches and parades, expres- sions of grief and anger, and celebrations of victory and joy. It played a key role in the events often referred to as the Stonewall Uprising or Rebellion, and has served as an important site for the LGBT community both before and after those events. As one of the only public open spaces serving Greenwich Village west of 6th Avenue, Christopher Park has long been central to the life of the neighborhood and to its identity as an LGBT-friendly community. The park was created after a large fire in 1835 devastated an overcrowded tenement on the site. Neighborhood residents persuaded the City to condemn the approximately 0.12-acre triangle for public open space in 1837. By the 1960s, Christopher Park had become a popular destination for LGBT youth, many of whom had run away from or been kicked out of their homes. These youth and others who had been similarly oppressed felt they had little to lose when the community clashed with the police during the Stone- wall Uprising. In the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, a riot broke out in response to a police raid on the Stonewall Inn, at the time one of the City’s best known LGBT bars. -

LGBT History

LGBT History Just like any other marginalized group that has had to fight for acceptance and equal rights, the LGBT community has a history of events that have impacted the community. This is a collection of some of the major happenings in the LGBT community during the 20th century through today. It is broken up into three sections: Pre-Stonewall, Stonewall, and Post-Stonewall. This is because the move toward equality shifted dramatically after the Stonewall Riots. Please note this is not a comprehensive list. Pre-Stonewall 1913 Alfred Redl, head of Austrian Intelligence, committed suicide after being identified as a Russian double agent and a homosexual. His widely-published arrest gave birth to the notion that homosexuals are security risks. 1919 Magnus Hirschfeld founded the Institute for Sexology in Berlin. One of the primary focuses of this institute was civil rights for women and gay people. 1933 On January 30, Adolf Hitler banned the gay press in Germany. In that same year, Magnus Herschfeld’s Institute for Sexology was raided and over 12,000 books, periodicals, works of art and other materials were burned. Many of these items were completely irreplaceable. 1934 Gay people were beginning to be rounded up from German-occupied countries and sent to concentration camps. Just as Jews were made to wear the Star of David on the prison uniforms, gay people were required to wear a pink triangle. WWII Becomes a time of “great awakening” for queer people in the United States. The homosocial environments created by the military and number of women working outside the home provide greater opportunity for people to explore their sexuality. -

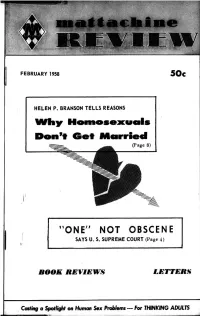

''One" Not Obscene Book Reviews Letters

FEBRUARY 1958 50c HELEN P. BRANSON TELLS REASONS Whx Homosexuals Don’t Get Married (Page 8) ’’ONE" NOT OBSCENE SAYS U. S. SUPREME COURT (Page 4) BOOK REVIEWS LETTERS Casting a Spotlight on Human Sox Problom s — For THINKING ADULTS ■ nattachf ne O ffici Of THf S04*D Of DI«ECrO*S inattachine ^rittg, M.. Copyright1 295S by the Matlacbine Society, incorporated FOURTH YEAR OF PUBLICATION-UATTACHIHE REVIEW founded January 1955 Mauaebint Foundation establisbid 1950; M<tttacbine*Society, Inc., ebartered 2954 OBSCENITY NEEDS TO BE DEFINED Volume IV FEBRUARY 1958 Number 2 The declaration by the U. S. Supreme Court that ONE magazine is not obscene (see page 4) is a victory for freedom of expression everywhere in the U. S., and not a gain for the 'homosexual press' Comtemt» alone. ARTICLES Changing times, changing attitudes and the general progress of human civilization call for old standards to be examined critically VICTORY FOR ONE by John Logan.........................................4 from time to time. The vague old bogey of obscenity is one of HOMOSEXUALS AS I SEE THEM by Helen P. Branson.. 8 these and within the past year or so sponsors of censorship on ob ENIGMA UNDER SCRUTING by Sexology Research Staff..14 scenity grounds have been called to task mote than once, but the right of Federal and State governments to judge and ban obscene SHORT FEATURES material has been upheld, as we believe it should be (see MATTA’ COURT RELEASES KINSEY MATERIAL..................................5 CHINE REVIEW. July 1957). We believe that ONE and MATTACHINE agree that freedom to CUSTOMS’ SEVEN-YEAR ITCH IS SCRATCHED............6 publish educational information, in an interesting and readable SOCIETY FOR THE SCIENTIFIC STUDY OF SEX..........7 form, on the subject of sex variation is a genuine service in the ARMY REVIEWS RISK DISCHARGES.......................................14 interest of truth, justice and human well-being. -

The President's Men'

Journal of Popular Film and Television ISSN: 0195-6051 (Print) 1930-6458 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjpf20 All the President's Men as a Woman's Film Elizabeth Kraft To cite this article: Elizabeth Kraft (2008) All the President's Men as a Woman's Film, Journal of Popular Film and Television, 36:1, 30-37, DOI: 10.3200/JPFT.36.1.30-37 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JPFT.36.1.30-37 Published online: 07 Aug 2010. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 78 View related articles Citing articles: 1 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjpf20 Download by: [Cankaya Universitesi] Date: 07 November 2016, At: 07:12 All the President’s Men as a Woman’s Film Bob Woodward (Robert Redford) and Carl Bernstein (Dustin Hoffman) on the steps of the Library of Congress. By Elizabeth Kraft Abstract: The author reads Alan J. lan J. Pakula’s 1976 film All the remained fascinated to this day by the Pakula’s 1976 film as a “woman’s President’s Men fits loosely into way the reporters, Carl Bernstein and film.” The vignettes focused on A several generic categories, firmly Bob Woodward, pieced together a case, women witnesses to the cover-up of into none. It is most often referred to as episodically and daily. the Watergate burglary reveal the pat- a detective film or a conspiracy thriller, The film partakes of other genres as tern of seduction and abandonment and certainly the whodunit narrative well.