Scottish Settlers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Laws - by State

Laws - By State Bill Name Title Action Summary Subject AL S 32 Civics Tests for Students 04/25/2017 - This law requires students enrolled in a public institution in Alabama to take the Education Enacted civics portion of the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services naturalization exam and score a 60 out of 100 prior to receiving a high school diploma. AL SJR 82 Bridge Designation 04/25/2017 - This resolution names a bridge after Johannes Whetstein and his family, who Resolutions Enacted immigrated to the U.S. in 1734, in order to recognize their contributions to the development of Autauga County in Alabama. AR H 1041 Application of Foreign 04/07/2017 - This law prohibits Arkansas institutions from applying foreign laws that violate Law Enforcement Law in Courts Enacted the Arkansas Constitution or the U.S. Constitution. AR H 1281 Human Services Division 04/05/2017 - This human services appropriations law includes funds for refugee resettlement. Budgets of County Operations Enacted AR H 1539 Naturalization Test 03/14/2017 - This law requires students enrolled in a public institution in Arkansas to take the Education Passage Requirement Enacted civics portion of the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services naturalization exam and score a 60 out of 100 prior to receiving a high school diploma. AR S 531 School for Mathematics 03/28/2017 - This law exempts U.S. residents who attend The Arkansas School for Education and Arts Provisions Enacted Mathematics, Sciences, and the Arts from paying tuition, fees, and housing, while requiring international students to pay for tuition, fees, and housing. -

Copyright by Christopher Newell Williams 2008

Copyright by Christopher Newell Williams 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Christopher Newell Williams certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: CAUGHT IN THE WEB OF SCAPEGOATING: NATIONAL PRESS COVERAGE OF CALIFORNIA’S PROPOSITION 187 Committee: ________________________________ Robert Jensen, Supervisor ________________________________ D. Charles Whitney, Co-Supervisor ________________________________ Gene Burd ________________________________ Dustin Harp ________________________________ S. Craig Watkins CAUGHT IN THE WEB OF SCAPEGOATING: NATIONAL COVERAGE OF CALIFORNIA’S PROPOSITION 187 by Christopher Newell Williams, BA; MS Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2008 Dedication To Sue, my wife and the love of my life, whose unwavering friendship, love and commitment made this long road incalculably easier to travel. Acknowledgments Many thanks to the faculty and staff of the School of Journalism at the University of Texas at Austin, who, in countless ways, offered a helping hand on this journey. More specifically, I’d like to thank my dissertation committee, whose guidance and wise counsel were essential in shaping this project. The original members were Chuck Whitney, Bob Jensen, Don Heider, David Montejano and Craig Watkins. After Don and David were no longer able to serve on the committee, Gene Burd and Dustin Harp graciously agreed to replace them. Many thanks to all of you for your work on my behalf. I’m especially grateful for the support of Chuck Whitney, the original chairman of my committee, whose wide-ranging knowledge and high standards enriched every chapter of the dissertation. -

2008 Backlist

Pelican Publishing Company BACKLIST CATALOG S African-American Interest . 56-57 Revolutionary War . 23 Antiques & Collectibles . 4 Southern History . 30 Architecture . 7-9 War of 1812 . 23 Louisiana Architecture . 9 World War II . 28 Majesty Architecture Series ...........................7 Holidays. 59-63 New Orleans Architecture Series .......................8 Christmas . 61 Art . 1-3 Halloween . 60 ONTENT Louisiana Art . 3 Hanukkah . 58, 61 C Mardi Gras Treasures Series by Henri Schindler . 3 Thanksgiving . 60 Biography & Autobiography . 37-40 The Night Before Christmas Series.................. 62-63 Louisiana Figures . 37 Humor . 19 Personal Memoirs. 40 Hurricanes. 36 Business & Economics. 46-47 Irish Interest . 55 Business Communication. 46 St. Patrick’s Day . 55 Entrepreneurship . 47 Judaica . 57-58 Kevin Hogan . 46 Music & Performing Arts . 5 Management . 47 Outlaws. 35 Sales & Selling . 47 Pirates . 40 Cartoons . 20-21 Poetry . 44 Best Editorial Cartoons of the Year Series . 21 Political Science. 22 Children’s Author Features . 45 Reference. 53 David Davis . 45 Genealogy . 53 Steven L. Layne . 45 Trivia . 53 Cookbooks. 10-18 Religion . 50-51 Frank Davis . 16 Dove Inspirational Press . 50 Jude Theriot . 17 Joe H. Cothen . 51 Justin Wilson . 17 Renaissance New Testament . 51 Restaurant Cookbooks . 10-11 Self-Help . 48-49 Family & Relationships. 52 Mike Hernacki . 49 Fiction & Literature. 41-44 Zig Ziglar . 48 George W. Cable . 43 Scottish Interest. 54 Harold Bell Wright. 43 Sports & Recreation. 67-69 James Everett Kibler . 43 Cruising Guide Series.............................. 67 Gardening & Nature. 6 Golfing. 69 Health. 52 Kentucky Derby . 68 History. 23-35 Travel. 64-67 19th Century . 29 Ghost Hunter’s Guides ............................. 67 20th Century . 29 International Travel . -

Ethnic Groups and Library of Congress Subject Headings

Ethnic Groups and Library of Congress Subject Headings Jeffre INTRODUCTION tricks for success in doing African studies research3. One of the challenges of studying ethnic Several sections of the article touch on subject head- groups is the abundant and changing terminology as- ings related to African studies. sociated with these groups and their study. This arti- Sanford Berman authored at least two works cle explains the Library of Congress subject headings about Library of Congress subject headings for ethnic (LCSH) that relate to ethnic groups, ethnology, and groups. His contentious 1991 article Things are ethnic diversity and how they are used in libraries. A seldom what they seem: Finding multicultural materi- database that uses a controlled vocabulary, such as als in library catalogs4 describes what he viewed as LCSH, can be invaluable when doing research on LCSH shortcomings at that time that related to ethnic ethnic groups, because it can help searchers conduct groups and to other aspects of multiculturalism. searches that are precise and comprehensive. Interestingly, this article notes an inequity in the use Keyword searching is an ineffective way of of the term God in subject headings. When referring conducting ethnic studies research because so many to the Christian God, there was no qualification by individual ethnic groups are known by so many differ- religion after the term. but for other religions there ent names. Take the Mohawk lndians for example. was. For example the heading God-History of They are also known as the Canienga Indians, the doctrines is a heading for Christian works, and God Caughnawaga Indians, the Kaniakehaka Indians, (Judaism)-History of doctrines for works on Juda- the Mohaqu Indians, the Saint Regis Indians, and ism. -

Highland Heritage: Scottish Americans in the American South'

H-South Sankey on Ray, 'Highland Heritage: Scottish Americans in the American South' Review published on Wednesday, August 1, 2001 Celeste Ray. Highland Heritage: Scottish Americans in the American South. Chapel Hill and London: University of North Carolina Press, 2001. xix + 256 pp. $16.95 (paper), ISBN 978-0-8078-4913-2. Reviewed by Margaret Sankey (Department of History, Auburn University ) Published on H-South (August, 2001) Living and Remembering a Constructed Past: Southerners and Highland Games My parents used to live next door to a family, who, despite a very German surname, were aggressively and professionally Scottish, to the extent that at any given time, one of their five children was taking bagpipe lessons, and they could be counted on to turn out for any parade or civic event in full Highland regalia. Celeste Ray, an anthropologist at the University of the South, has produced an explanation and an examination of this phenomena, particularly as it is experienced in the southern United States. Based largely on her interviews and observations at a number of regional Highland Games, Ray has produced a fascinating account of a comparatively modern (post WWII) movement amongst Scottish Americans to construct a heritage. Interestingly, this is one in which recent changes in gender roles and family structure are replaced by a highly militarized and male- dominated culture. This new "Highland Heritage" is an eclectic blend of Highland and Lowland Scottish traditions, melding the lowland "Burns' Supper" with Highland attire and, strangely, the lowland religion (Presbyterianism). In many ways, this syncretic approach smoothes over the potential historical and cultural fault lines among Scottish Americans, including differences in dates of emigration, the awkwardness of Scottish loyalism in the American Revolution, and the distinctive feuds between opposition groups in Scotland. -

SYLLABUS-BECOMING SCOTTISH AMERICANS.Pdf

1 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS OLLI BECOMING SCOTTISH AMERICANS Fall 2020 Instructor Contact Information Loarn Robertson E-mail: [email protected] ‘Loarn’ You can expect to receive a reply from your instructor within 24 hours if you email during the week, or within 48 hours on the weekend COURSE SYLLABUS COURSE DESCRIPTION In the early 17th century settlers were sent to North America by the new ‘British’ King James 1st. He hoped to establish permanent colonies there. These early settlers included Scots from the Highlands and Lowlands who came, initially, as traders, trappers, planters and others as indentured servants and prisoners from religious and civil wars in Britain. Many settled, married with the native population rearing families establishing communities while often maintaining Scottish traditions. In the 18th and 19th centuries these early settlers were followed by others, some seeking a better life, some as banished plantation prisoners, some as soldiers and many fleeing poverty and persecution because of their beliefs or heritage often being dispossessed of their property and livelihood. In the 20th century another wave of immigrants arrived as a result of the industrial depression following the collapse of Scottish heavy industries and their affiliated raw materials suppliers. Although, as an ethnic group, the immigrant Scots were relatively small in number, they and their descendants were to help forge these United States and many were to create lasting impressions on the American landscape establishing economic, political and cultural legacies that are recognized and revered today. This is the story of those Scottish emigrants, their motivations, failures and successes as individuals and groups who took the risks and faced the challenges involved in becoming Scottish Americans. -

Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies After the Homecoming

Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Volume 5: Issue 2 After the Homecoming AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies, University of Aberdeen JOURNAL OF IRISH AND SCOTTISH STUDIES Volume 5, Issue 2 Spring 2012 After the Homecoming Published by the AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies at the University of Aberdeen in association with The universities of the The Irish-Scottish Academic Initiative ISSN 1753-2396 Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham and Eastbourne Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies General Editor: Cairns Craig Issue Editor: Michael Brown Editorial Advisory Board: Fran Brearton, Queen’s University, Belfast Eleanor Bell, University of Strathclyde Ewen Cameron, University of Edinburgh Sean Connolly, Queen’s University, Belfast Patrick Crotty, University of Aberdeen David Dickson, Trinity College, Dublin T. M. Devine, University of Edinburgh David Dumville, University of Aberdeen Aaron Kelly, University of Edinburgh Edna Longley, Queen’s University, Belfast Shane Alcobia-Murphy, University of Aberdeen Ian Campbell Ross, Trinity College, Dublin Graham Walker, Queen’s University, Belfast International Advisory Board: Don Akenson, Queen’s University, Kingston Tom Brooking, University of Otago Keith Dixon, Université Lumière Lyon 2 Marjorie Howes, Boston College H. Gustav Klaus, University of Rostock Peter Kuch, University of Otago Graeme Morton, University of Guelph Brad Patterson, Victoria University, Wellington Matthew Wickman, Brigham Young David Wilson, University of Toronto The Journal -

Smithsonian Folklife Festival Records: 1967 Festival of American Folklife

Smithsonian Folklife Festival records: 1967 Festival of American Folklife CFCH Staff 2017 Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage 600 Maryland Ave SW Washington, D.C. [email protected] https://www.folklife.si.edu/archive/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical note.................................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Contents note................................................................................................ 2 Arrangement note............................................................................................................ 2 Introduction....................................................................................................................... 3 Participants....................................................................................................................... 4 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 5 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 7 Series 1: Program Books, Festival Publications, and Ephemera, 1967................... 7 Series 3: Photographs............................................................................................. -

2017 Laws and Resolutions by Subject

Laws - By Subject Bill Name Title Action Summary Subject Human Services Division of 04/05/2017 - AR H 1281 County Operations Enacted This human services appropriations law includes funds for refugee resettlement. Budgets This appropriations law establishes the distribution of funds for criminal justice Criminal Justice and Budget 05/12/2017 - agencies in Arizona. Budgets have been established for agencies such as the AZ H 2540 Reconciliation Enacted Gang and Immigration Intelligence Team Enforcement Mission. Budgets This appropriations law establishes how funds will be distributed to different agencies in Arizona. The Gang and immigration intelligence team enforcement 05/12/2017 - mission agency will receive funds so that it can fulfill its mission to enforce AZ S 1522 General Appropriations Act Enacted federal laws regarding illegal immigrants. Budgets This budget law prohibits local law enforcement agencies from entering into or modifying a contract with the federal government after June 15, 2017, to house or detain an adult noncitizen in a locked detention facility for civil immigration 06/27/2017 - custody. The law similarly prohibits detention of accompanied or CA A 103 Public Safety: Omnibus Enacted unaccompanied minors except for temporary housing. Budgets This appropriations law includes funding for immigrant integration, migrant 06/27/2017 - housing, English as a second language and legal services for unaccompanied CA A 97 Budget Act of 2017 Enacted undocumented minors. Budgets School Finance: Education 06/27/2017 - CA A 99 Omnibus Trailer Bill Enacted This school finance law includes funding for refugee pupils. Budgets This law expands legal services for which grants are available to refer to "immigration remedies," authorizing grants to qualified organizations to provide legal training and technical assistance. -

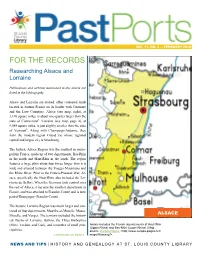

FOR the RECORDS Researching Alsace and Lorraine

VOL. 11, NO. 2 — FEBRUARY 2018 FOR THE RECORDS Researching Alsace and Lorraine Publications and websites mentioned in this article are listed in the bibliography. Alsace and Lorraine are storied, often contested lands located in eastern France on its border with Germany and the Low Countries. Alsace (see map, right), at 3,196 square miles, is about one-quarter larger than the state of Connecticut1. Lorraine (see map, page 4), at 9,089 square miles, is just slightly smaller than the state of Vermont2. Along with Champaign-Ardenne, they form the modern region Grand Est whose regional capital and largest city is Strasbourg. The historic Alsace Region was the smallest in metro- politan France, made up of two departments, Bas-Rhin in the north and Haut-Rhin in the south. The region features a large plain about four times longer than it is wide and situated between the Vosges Mountains and the Rhine River. Prior to the Franco-Prussian War, Al- sace, specifically the Haut-Rhin, also included the Ter- ritoire de Belfort. When the Germans took control over the rest of Alsace, it became the smallest department in France, and was attached to Franche-Comté and is now part of Bourgogne- Franche-Comté. The historic Lorraine Region was much larger and con- sisted of four departments, Meurthe-et-Moselle, Meuse, Moselle, and Vosges. The territory included the histori- ALSACE cal Duchy of Lorraine, Barrois, the Three Bishoprics (Metz, Verdun, and Toul), and a number of small prin- Alsace includes the French départements of Haut-Rhin (Upper Rhine) and Bas-Rhin (Lower Rhine) | Map cipalities. -

View Festival Brochure

Membership THE MAKING OF AMERICA A Citywide Festival Starts at Carnegie Hall on March 9 Events Across New York City Begin February 28 THETHE MAKING MAKING OFOF AMERICAAMERICA he history of America is indelibly linked to the movement Trace Your Ancestry of people. Some were brought here not of their own free will, and their perseverance and resilience transformed Where are you from? Enter our Trace Your Ancestry contest and answer that question. the nation. Others came here—or moved within the borders of Our partners at the New York Genealogical this country—because they sought a new life, free from poverty, and Biographical Society—New York’s oldest discrimination, and persecution. The many contributions— and largest genealogical institution—will cultural, social, economic, and political—of these migrations, and provide 20 hours of professional genealogical the people who helped to build this country and what it means to research ($2,500 value) for one lucky winner. be American, are honored in Carnegie Hall’s festival Migrations: Learn about your ancestors and their stories, while also discovering something about yourself. The Making of America. For official rules and to enter, visit: At Carnegie Hall, we examine the musical legacies of three carnegiehall.org/TraceYourAncestry migrations: the crossings from Scotland and Ireland during the 18th and 19th centuries, the immigration of Jews from Russia and Eastern Europe between 1881 and the National Origins Act of 1924, and the Great Migration—the exodus of African Americans from the South to the industrialized cities of the Northeast, Midwest, and West from 1917 into the 1970s. -

Morness Pdf (386.4Kb)

UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN - EAU CLAIRE “I LIFT MY LAMP BESIDE THE GOLDEN DOOR”: A COMPARISON BETWEEN SCOTTISH AND IRISH IMMIGRANTS IN NEW YORK DURING THE NINETEENTH CENTURY A SENIORTHESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY DR. JOHN MANN, PROFESSOR COOPERATING PROFESSOR: DR. LOUISA RICE WRITTEN BY: REBECCA MORNESS EAU CLAIRE, WISCONSIN MAY 2011 Copyright for this work is owned by the author. This digital version is published by McIntyre Library, University of Wisconsin Eau Claire with the consent of the author. 0 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT .....................................................................................................................................2 INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................3 BACKGROUND INFORMATION ................................................................................................4 WHY DID THEY IMMIGRATE? SCOTTISH ..........................................................................................................................9 IRISH .................................................................................................................................11 WHO WERE THE IMMIGRANTS? SCOTTISH ........................................................................................................................12 IRISH .................................................................................................................................13 WHY WAS RELIGION SO IMPORTANT?